Supply chain disruption: Why this is no short term consequence of COVID and the huge role private equity will play

If you cycle, play golf, ski or mountain climb, chances are that you might have bent down to tighten your shoes using a BOA lacing system. This lacing system enables you to tighten your shoe simply by turning a dial that connects the laces to a plastic-coated wire.

BOA is an investee of Compass Diversified Holdings (CODI:NYSE), an NYSE-listed middle market buyout fund whose other investees include consumer brands such as Ergo Baby, 5.11 Tactical, Marucci Sports.

BOA lacing systems are proving extremely popular. Demand for them is soaring but the biggest factor holding back BOA’s profitability, which is very strong, is not labour shortages or cost inflation – although it is experiencing both of these – but supply chain disruption. In fact, as our investees were reporting Q4 2021 results in Q1 of 2022, supply chain disruption surprised us as being the biggest theme impacting results that no-one was talking about. Well, that’s not quite true. It was being talked about but it was generally being bracketed together with labour shortages and cost inflation as one of a number of business headwinds.

The CEO of Compass Diversified, Elias Sabo, however, put BOA’s supply chain predicament very plainly. He explained if there’s demand for your product but you can’t supply it, you can’t generate a sale. For a strong consumer brand like BOA, cost inflation may not be desirable, but it can generally be passed onto the consumer meaning sales and profits can be generated. Similarly, labour shortages can be dealt with by paying workers more. But supply chain disruption on the scale that is being experienced means that sales are completely forgone - or at best postponed.

"In order to combat supply chain issues, we have chosen to significantly increase our inventory levels. However, a significant amount of our inventory at year-end remained in transit and unavailable for delivery. We experienced a steady decline in warehouse deliveries throughout the fourth quarter with an offsetting increase in our in-transit inventory." Elias Sabo, CEO Compass Diversified

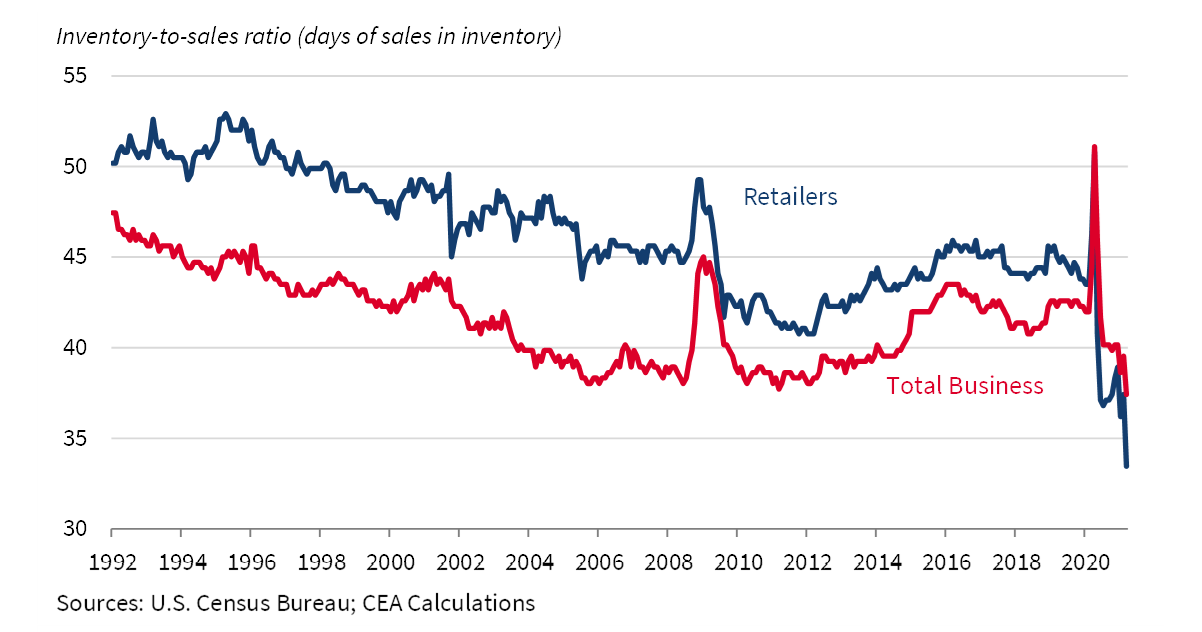

In the face of elevated demand and supply limitations, businesses have been forced to run down inventories to record lows.

Most of the supply chain disruptions being experienced seem to be traceable to COVID induced shutdowns and bottlenecks but there are also more enduring structural changes afoot. As supply chains are now so complex and interconnected, it’s often very difficult to discern and pinpoint where the real issues exist. It is very clear, however, that many factories and transport networks were shutdown as a result of COVID and with most businesses shifting to best-practice just-in-time inventory management, businesses have not been in a position to respond to the unanticipated surge in discretionary consumer spending upon the re-opening from lockdowns.

Many of the private-equity backed companies we monitor like BOA are responding to the supply chain disruptions by building up inventories or moving production closer to their home ports. Based on the anecdotes we’re hearing, we’re very concerned that these higher inventory levels could become a new normal. If higher levels of working capital become the new normal, it will be reflected in lower equity valuations.

Most of the supply chain commentary has been around the disruptions to major industries such as the car industry and the electronics industry. As has been well-reported, these sectors have been particularly impacted by a shortage of semiconductors. The average electric car today has more than 2,000 semiconductor chips whilst the average combustion engine car has several hundred chips. In fact, today the electronics in a car account for 40% of the total production cost. When the demand for new cars plummeted in 2020 at the onset of covid, car manufacturers cut their orders for semiconductors and the manufacturers shifted their production lines to other applications. Today, the gap between semiconductor chip order and delivery times range between 18 weeks and 6 months, whereas pre-pandemic wait times hovered around12 weeks. This is resulting in cashed up consumers having to wait 12 months or more for new cars to roll off the production line.

On the subject of semiconductors, it is worth noting that the largest semiconductor manufacturer in the world is Taiwan Semiconductor (TSMC), accounting for approximately 45% of all world supply. Taiwan Semiconductors supply to companies including Apple, Nvidia and Qualcomm. Following the invasion of Ukraine and the speculation that China could move to seize Taiwan, it would not be surprising for this to be the impetus for many companies to “reshore” their semiconductor supplies to create a more “resilient” supply chain. In fact, long before Russia invaded the Ukraine, geopolitical factors were driving the redesign of supply chains, many of which were entirely dependent on China when costs were the only consideration. Today supply security and supply chain resilience factor more heavily in supply chain design.

While the shortage of cars and semiconductors has been widely reported, we’re seeing supply chain disruption right across our portfolio. Some examples of some private equity-owned businesses experiencing extreme supply chain disruption include:

1. Marucci Sports – the second largest baseball brand. It had to go to great lengths to ensure it had product on the floor for the holiday season, including sacrificing margin to air-freight stock to capture additional floorspace offered by a major retail sporting goods chain.

2. ADT – The USA’s largest monitored security and residential solar services company. It reported most recently that previously commonplace on-demand parts orders now have a waiting period of weeks to months. As well as adding additional suppliers, the challenge has been to better forecast demand and schedule labour in advance.

3. North Sails – the global leader in sails has seen a huge recovery in demand on the resumption of competitive and recreational sailing in 2021. Even though they produce all their sails in-house in one of seven owned and operated production facilities around the world, they have had to contend with pandemic-related impacts on manufacturing operations and limitations of global logistics capacity.

Shipping and transport have clearly been a major source of supply chain disruption. Many of the problems are logistical but some are more structural in nature. The logistical problems at the port of Los Angeles which accounts for 40% of the containerised imports exemplify the challenges being felt across the system. Some of the reasons for the disruption are:

1. Imbalance of trade – in January 2020, the Port of Los Angeles reported that there were 427,207 loaded containers imported compared to 100,185 loaded containers exported. The simple fact is, the USA imports a lot more stuff from China than it exports. This has meant containers have banked up in the USA which has contributed to a disruptive container shortage in China.

2. Loading times have increased – labour shortages have contributed to slower turnaround times.

3. Increases in freight costs – the cost of shipping a container from China to the USA is now 16 times the return trip (pre-pandemic it was three time greater). This has meant that ships now must wait until they are full which is contributing to slower turnaround times.

4. Port shut downs – Covid disruptions has meant various ports in China have been completely shut down which has contributed to a backlog that needs to be cleared.

Some of the more structural issues contributing to higher freight costs and slower shipping times are:

1. Geopolitical risks – the recent tit-for-tat trade war between China and the US, trade bans (such as China’s ban on Australian wine and lobsters), not to mention tensions around Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine and the political tensions around China and Taiwan has meant a shift to “reshoring” supply chains.

2. Response to Covid Supply Chain disruption – the disruptions experienced during covid have accelerated the trend towards building supply chain “resilience” by having alternative suppliers and diversifying suppliers by geography.

3. De-carbonization and energy transition – with companies under increasing pressure to reduce their carbon footprints, there is a global trend towards “near-shoring”.

So we’re watching these supply chain trends very closely. But based on anecdotal evidence, we think it is likely that sales at many companies are going to be impacted, not just over the remainder of this year, but significantly longer. Whilst these trends concern us, we’re also seeing some reasons to believe supply chains will continue to become more efficient.

Private Equity-backed Innovation in Transport and Logistics

The transportation and logistics sector has been a key area of private equity investment well before the onset of the pandemic. Private equity backed transactions have accounted for approximately a third of total mergers and acquisitions in the sector. Aside from the e-commerce driven growth in demand for logistics, it is a sector which is highly fragmented, inefficient due to high operational complexity, and has suffered from under-investment for years in terms of people, processes and technology.

There is a lot of innovation in transport and logistics which ultimately means a lower cost of goods for consumers. Some of the examples we’ve come across include:

Ship size – in 2007 the largest ships carried 8,000 containers (each of which can fit the contents of an average 3 bedroom house). Today the largest ships (such as the Evergreen which got stuck in the Suez canal) can carry 24,000 containers. This 3.5 fold increase has meant a big fall in unit transport costs.

Autonomous Shipping – labour levels are down dramatically. Some of the largest ships now set sail with a crew of 20 and autonomous shipping is not far away. Already ships are using very sophisticated route optimisation that takes into account wind, currents and waves. The obvious route is no longer the shortest route.

Container Design – The ubiquitous 20ft and 40ft containers have revolutionised shipping since they became widely used in the 1970s but a company called Holland Containers has designed a container than can be folded when empty to a quarter of its size. As 20% of containers shipped on sea and 40% transported on land are empty, this “simple” innovation reduces the unit cost of transporting empty containers by a quarter.

Blockchain – the digital record keeping technology behind crypto currencies could be a game changer in shipping. The financial ledgers and enterprise resource planning systems now used don’t reliably allow the three parties involved in a simple supply-chain transaction to see all the relevant flows of information, inventory, and money. A blockchain system would eliminate the blind spots and eliminate costly manual audits, the costs of lost inventory etc.

This pace of innovation is only going to continue. Supply-chain technology start-ups, particularly in automation and software tools for managing warehouses, freight and fleet management, raised a record $24.3bn in the first three quarters of 2021. On the other end of the size spectrum, Blackstone’s $280bn global real estate business, 40% is comprised of logistics assets including warehouses, distribution centres and ports. Locally in Australia, KKR is setting up a new fund with Centennial Property Group to acquire warehouse and logistics sites.

Ultimately, we believe private equity will continue to play a big role in supporting this innovation in transport and logistics but we believe supply chain issues are going to continue to drive up costs and lower profits for the foreseeable future. We’re convinced that we’re witnessing much more than a “covid blip” – the reconfiguring of supply chains is going to play out over years to come.

3 topics