Swap spreads to tighten as the bond-premium fades

Coolabah Capital

Swap spreads are being driven by expensive bonds

In advance of next week’s roll, Aussie swap spreads have widened to extremes last seen just prior to the December quarterly roll. While there is speculation that this might be driven by higher bank funding cost, our analysis shows that the far bigger factor is the rise in the premium of Commonwealth government bonds over the RBA’s cash rate, which is likely to dissipate sharply as the net supply of Commonwealth debt spikes in coming months.

A few months ago, we published a fundamental model of 10-year Australian swap spreads. Recall that these spreads reflect the difference between the 10-year swap rate and the yield on a 10-year Commonwealth government bond (or a 10-year Commonwealth government bond futures contract).

Our bottom line was that one can think of these 10-year swap spreads as the sum of three key forces: (1) bank funding costs; (2) the premium of Commonwealth government bonds over a maturity matched RBA cash rate expectation (aka the “bond premium”); and (3) what we call the “basis”, which is all other factors. These other factors can include forward repo rates, the bond basket arbitrage, and other influences. Significantly, these other variables are far less important than the first two factors.

Key Drivers of Swap Spreads

Centrally-cleared swap spreads have no counterparty credit risk, but there is an influence via our first factor, which is bank funding costs. This is proxied by the expected difference between the 6 month bank bill swap rate (BBSW) and the RBA’s cash rate. We use overnight index swaps (or OIS) to gauge expectations for the RBA’s cash rate.

The second factor, that we call the “bond premium”, represents the difference between the relevant Commonwealth bond yields and OIS. Greater demand for bonds tends to reduce their yield, relative to OIS.

Higher bank funding costs tend to push swap spreads wider while a lower bond premium has the opposite impact.

A simple two-factor model, including only term bank funding costs and the bond premium explains around 95% of the variation in 10-year Aussie swap spreads.

The market narrative surrounding the recent widening has been that tighter funding conditions, due to funding pressures and the war in the Ukraine, have worsened bank credit and so pushed out swap spreads.

This narrative has been encouraged by the higher (spot) 6mth BBSW fixings. However, we don’t think it is the full story. 10-year swap spreads are much more driven by term bank credit spreads (expected 6m BBSW v. OIS over the next 10yrs). Specifically, the widening of 10-year 6mth BBSW v. OIS explains at most ~5bps of the widening of 10-year swap spreads since their 19 January tights.

In any case, the spread between term bank credit (10-year 6mth BBSW v. OIS) has normalised back to around its average pre-pandemic levels in the low 30bps area. Since Aussie banks are benefiting from strong deposit inflows and a have very modest funding gap (less than $130 billion a year for the next 3 years; based on our credit analysts’ estimates) term bank credit (10-year 6mth BBSW v. OIS) is unlikely to push wider than average.

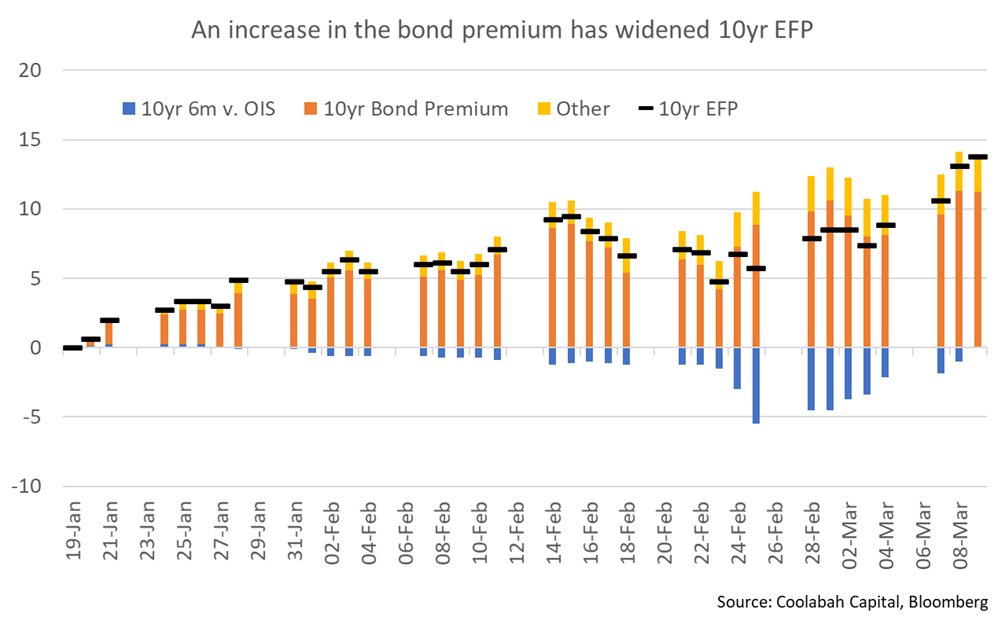

When we decompose 10-year swap spreads into the (1) bank funding cost and (2) the bond premium factors, we can see that almost all of the widening, from the 19 January tights, is due to an increase in the bond premium (ie, bond yields are lower relative to OIS). See the first chart below.

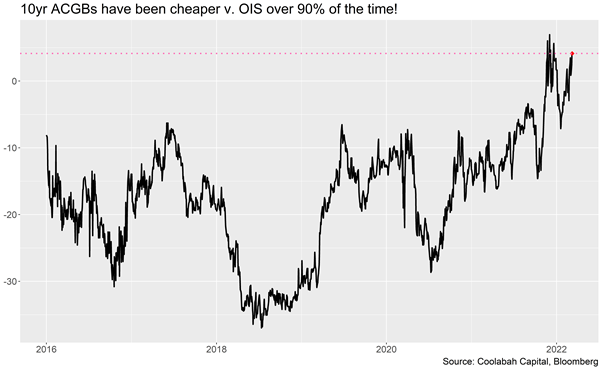

Accordingly, the story here is not really about bank funding costs, but much more about the bond premium (chart below). The richening of Commonwealth bonds relative to OIS has taken the bond-premium to an historical extreme. At present levels, it’s in the top 10% of the historical distribution (since the introduction of central clearing, in 2015) and at a similar level to December 2021.

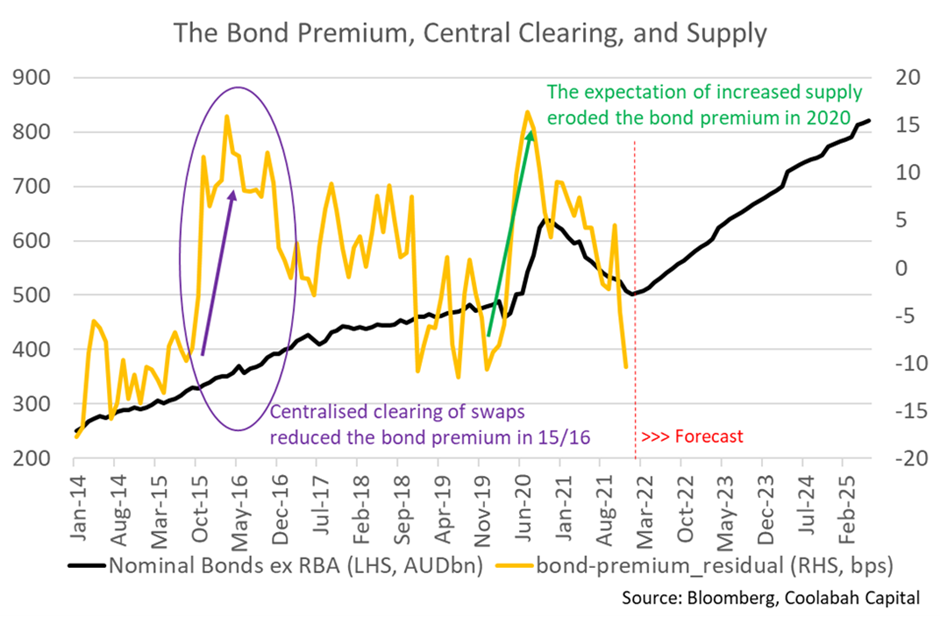

We had a close look at the bond premium in our original swap-spread paper. We found that the bond premium tended to move with the gross supply, and free float of, Commonwealth Government bonds.

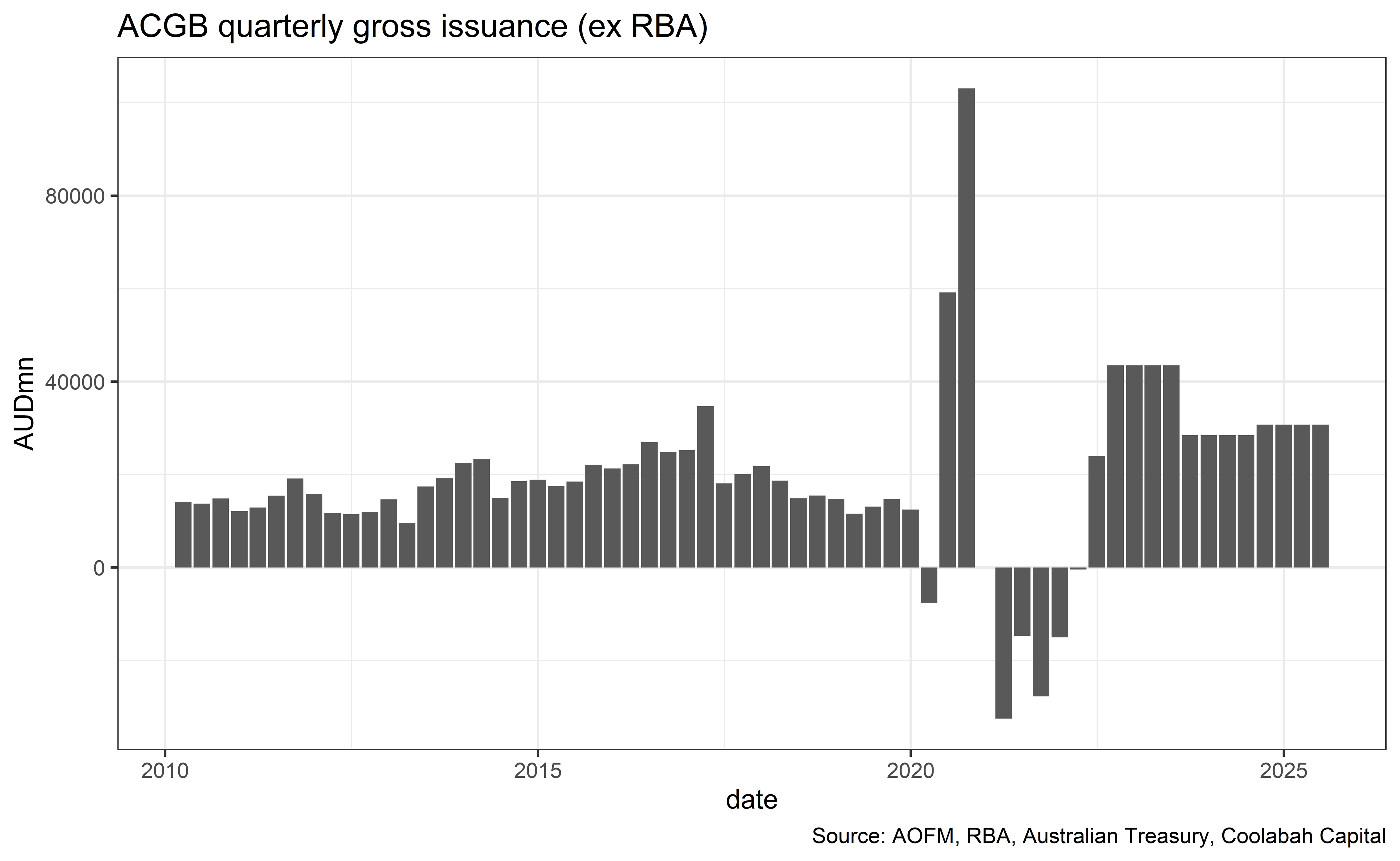

With the RBA no longer buying Commonwealth bonds, gross supply is positive and the free float is increasing (see first chart below). While the end of QE and resumption of net supply hasn’t had much of an impact on the bond premium thus far, investors should note that the AOFM has issued less than $10bn since the end of QE.

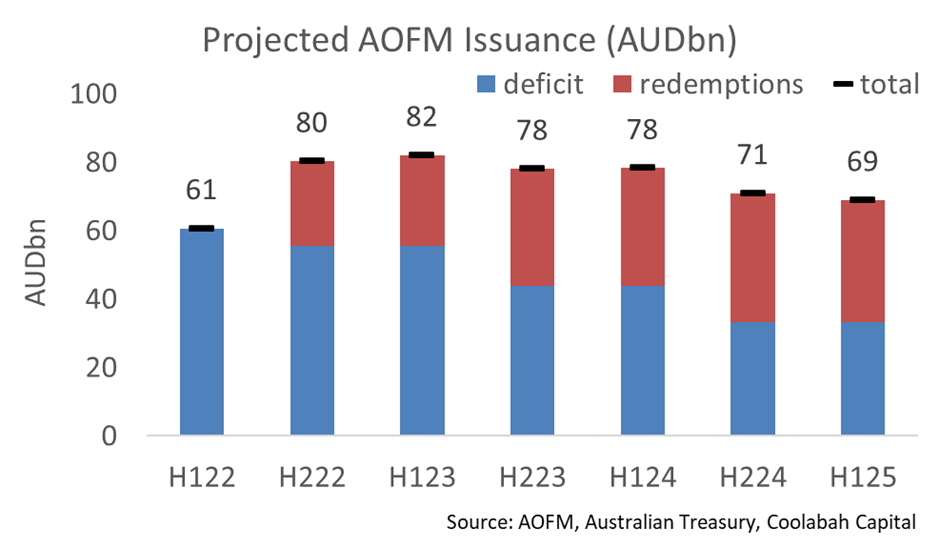

Looking ahead, the syndication of the November 2033 Commonwealth bond, probably in April 2022, is likely to dwarf what we’ve seen so far (the 11/32 in April 2021 was a $14bn deal). AOFM issuance, net of RBA buying, will rise from negative last year and earlier this year to positive ~$80 billion each half year, and as this fills in balance sheets we’d expect the bond premium to decline (see second chart below).

The change in gross issuance is large: for calendar year 2021, gross issuance excluding RBA purchases was minus $90 billion. This will rise by about $200 billion to $110 billion in 2022, and by a further $30 billion to $140 billion in calendar year 2023.

The exact profile from quarter to quarter will largely be determined by how the AOFM deals with maturities. In particular, the $85 billion of maturities in 2022-23 may be pre-funded, which may boost gross issuance in first half 2022, and mean that the AOFM can gross-issue less than $40 billion per quarter in second half 2022 and first half 2023.

Conclusion

The recent widening of Australian swap spreads has been variously blamed on the conflict in the Ukraine and stress in funding markets. While it’s true that some these factors have had an influence, the proxy for banking funding costs, namely the 10-year 6m BBSW v. OIS, is at time of writing (9 March 2022) around its average historic level, and, significantly, no different to its January 2022 level.

What is crucially different today is that Commonwealth bonds have richened sharply relative to OIS and are now at extreme levels. We expect Commonwealth bonds to cheapen relative to OIS as the AOFM ramps up issuance to both refinance existing maturities and to fund the ongoing budget deficit. The change in the gross-supply of Commonwealth bonds, net of RBA purchases, is large (AOFM issuance less RBA buying), as the final chart below shows. This reflects the very large size of the RBA’s QE program, relative to AOFM issuance (the RBA’s Bond Purchase Program concluded on 10 February).

We see current fair value at ~20bps, falling into a range of 10bps to 15bps over time as gross supply increases and the free float of bonds rises.

2 topics

Matt is a portfolio manager at Coolabah Capital, an asset manager than runs over $8 billion in fixed-income strategies. Matt has 17 years of experience on both the sell-side and buy-side. He spent most of his career (2008 to 2020) at UBS, the...

Matt is a portfolio manager at Coolabah Capital, an asset manager than runs over $8 billion in fixed-income strategies. Matt has 17 years of experience on both the sell-side and buy-side. He spent most of his career (2008 to 2020) at UBS, the...