Tariffs: Making the U.S. Exceptional, but not in a good way

The tariffs that the U.S. is imposing on its trading partners will bring about several costs that are important for investors to understand. Some of those costs are inherent to what a tariff is, while others stem from the fact that U.S. industrial policy has, and looks to continue to have, a huge amount of uncertainty associated with it. That continuing uncertainty will hit investment levels, return on capital and overall growth globally, with the U.S. bearing the brunt of it. Beyond the uncertainty, tariffs should reduce the fair value of currencies against the U.S. dollar in the shorter term, although the impact will be smaller if countries retaliate (our base case) than if they do not. Tariffs also will hit the profits of most companies that do business in the U.S., including high-quality companies with significant market power, like the Magnificent Seven. For lower-quality companies, this hit may be enough to drive some into bankruptcy. That increased bankruptcy risk alongside generally tight credit spreads means that U.S. high yield corporate credit looks to be a particularly bad risk/reward trade-off. While tariffs are also inherently inflationary, we believe the risks to U.S. Treasuries are more balanced than they are for U.S. corporate credit or U.S. stocks, and we continue to believe that non-U.S. stocks are a better risk/reward trade-off than most stocks in the U.S. The strong absolute and relative performance of GMO's Asset Allocation strategies during the first quarter demonstrates the potential for valuation-sensitive strategies to add value during these uncertain times.

Click to read Part 1 of the Quarterly Letter, Trade: The Most Beautiful Word in the Dictionary, a companion piece that looks at the economics of trade and tariffs at a somewhat more theoretical level.

As we wrote in our first piece, (1) we believe the current path the Trump administration appears to be going down with regard to global trade is misguided. It attempts to fix problems that aren’t actually problems and is a needlessly economically expensive way to achieve the goals we think the administration is trying to achieve. But those critiques are not hugely relevant for investors navigating the markets today. The world is never perfect, government policy is never ideal, and investors need to make decisions under both uncertainty and the drag of imperfect policies.

Tariffs, whether or not a good idea, can be expected to have some pretty clear impacts on assets that matter to investors. In this second piece, we will go through our views on the impacts across three different assets classes – currencies, equities, and corporate credit. The details matter. Tariffs on specific countries or products lead to meaningfully different outcomes than broad-based tariffs that impact all countries and products, and tariffs that inspire retaliation have different impacts than those that are purely unilateral. Our hope is to explain the framework we are using to make our analysis, rather than present firm conclusions about what assets may do given our current guess as to what policy will ultimately be. Given the fluid nature of policy at the moment and a lack of clarity on which proposals (or social media posts) are negotiating tactics and which are likely to be enacted, a framework strikes us as much more useful than specific forecasts.

Uncertainty bites

Before we get to the impacts we believe tariffs will have, it seems worthwhile to spend a bit of time talking about uncertainty. It has been particularly challenging to draw conclusions given the almost continual changes coming from the administration as to what tariffs will be imposed, on whom, and when. Indeed, we’ve ripped up and rewritten several versions of this paper as the likely path of policy has changed. But the troubles of those of us who write about ever-changing trade policies are nothing compared to the troubles of those who have to manage their businesses through them. Tearing up and rewriting a paper is a matter of a few hours of work. Tearing up and rebuilding a supply chain or a capital stock is the work of years and huge sums of money, and getting things wrong could result in the destruction of entire businesses. While we believe that imposing meaningful tariffs on imports will hurt the U.S. economy and the world, the implications of the profound and ongoing uncertainty about what will happen, when, and for how long seem likely to be significantly worse.

Corporations are forced to make high-stakes, long-term investments on a continual basis. Policy uncertainty, which makes that task harder, has two important implications. First, corporations are likely to invest less than they otherwise would. Not only is there a strong tendency to put off decisions until there is more clarity – a dynamic that should be slowing activity today and in the near future – but when corporations are less confident in the return on existing investments, they’re more likely to turn down new ones. Second, while some of a corporation’s investments may deliver surprisingly high returns as one piece of policy or another winds up benefitting them, in expectation the return on investment will fall. Unfortunately, this applies not merely to new investments that corporations make, but their current capital stock as well. Given how large a fraction the U.S. economy is of global goods trade, few companies and countries will remain entirely unaffected. But it is those companies that do more of their business in the U.S. who are likely to experience the greatest impacts. While it might seem like the current period of uncertainty should end quickly once the administration finalizes their proposals, the poorly designed nature of many of these policies makes it hard to have confidence that they will last in their current form, irrespective of the number of capitals in the late-night social media posts that announce them.

A straightforward example of this problem is the copper tariffs the administration is considering. The ostensible goal of the tariffs is to incentivize increased domestic production of copper. Given that U.S. copper imports today come mainly from Chile, Canada, and Peru, it is not entirely obvious that national security is truly at risk should the status quo continue. (2) But taking the goal of increased domestic production of copper as a given, imposing a large tariff on imported copper now seems an inefficient and costly way to achieve it. Copper mines take years of development before they can produce any copper. In the meantime, the cost of copper in the U.S. will be substantially higher than it is anywhere else in the world. This will enrich the current copper producers, but it will also inflict at least twice as much pain on the much wider array of copper consumers across the U.S, since the U.S. consumes twice as much copper as it imports.

The existence of substantial tariffs on copper imports would indeed incentivize investment in new domestic copper mines, but only if those tariffs are assumed to last long enough to substantially benefit the mine’s output. A mine, once operational, will run for decades – so uncertainty about the duration of the tariffs will reduce the incentive to invest today. A future administration, even if it shared exactly the same goal of increased domestic copper production, might well decide a more efficient way to incentivize that would be to subsidize the investment in copper mines. There are a number of benefits to this approach. Since the investment takes place over a shorter period than a mine’s output, there is less uncertainty about whether the policy will last long enough to justify the investment. The costs are also very directly tied to increased copper production, which makes it a much more efficient policy. Even if copper consumers were to pay 100% of the cost of the subsidy — say through a relatively small tax on copper consumption or copper imports — that cost would be much lower than the wider costs of a larger tariff on copper imports. (3)

And if you did have some inkling that the administration might pivot to such a policy (or that a future administration would), that should make you less likely to want to invest in copper capacity now, even after the tariffs are put on. If future investors may get a subsidy that you don’t, and the tariffs you are counting on may not stay in place, investing in that copper mine today looks much less enticing – arguably even less appealing than it would have been had tariffs not been applied in the first place. A big part of the problem with badly designed policies is that they are less likely to stick even when enacted with great fanfare. When the costs of such policies hit immediately and reaping their benefits requires a belief that the policies will be permanent, uncertainty and costs associated with that uncertainty take a very long time to dissipate and benefits are unlikely to materialize.

The end result of that lingering uncertainty is a U.S. economy that deploys capital less efficiently, is less competitive globally, and grows more slowly than it otherwise would have.

Short-term, tariffs should strengthen the Dollar

The reason to want a foreign currency is pretty simple: you want to buy something that you can’t with the currency you have in hand. A lot of the time that "something" is actual stuff, like goods or services. The rest of the time that something is an investment asset; mostly stocks and bonds, but perhaps if you have a fair bit of spare cash and want to be chums with the President, it can be a factory or lots of AI infrastructure.

Changes to currency exchange rates are really all about fluctuations in demand for the various things those currencies can buy. If the demand for foreign assets goes up – as it might if overseas interest rates rise – the domestic exchange rate will weaken (i.e., the local currency will buy less of the foreign currency). If the demand for foreign goods goes down, as one might expect if import tariffs are enacted, the domestic exchange rate will instead strengthen.

Consider, for instance, what would occur if the U.S. were to impose a 25% tariff on Mexican goods. Mexico exports a variety of things to the U.S., including cars, computers, petroleum, beer and a surprisingly wide array of seats. (4) While these are important goods for U.S. companies and consumers, most of them are produced in highly competitive industries that exist in many different locations. If getting them from Mexico suddenly became a lot more expensive, the U.S. would shift to importing these goods from elsewhere (at higher prices and lower quantities). Mexico – for whom exports to the U.S. are a whopping 25% of economic output – would likely produce less of most of these goods and sell a larger fraction of them to other countries. The overall demand for Mexican goods, and therefore for Mexican pesos, would almost certainly decline. (5) This would, all else equal, place upward pressure on the American dollar and substantial downward pressure on the Mexican peso.

Today, American imports tariffs on Mexico are (unfortunately) a reality. Yet the Mexican peso has been basically flat since the U.S. presidential election. There are several potential counterweights to local currency strengthening in the presence of imports tariffs – beyond the hope that those tariffs might soon be cancelled – that help explain this:

1. The tariff might be circumvented through trade rerouting.

This is only possible if tariffs are imposed to some countries but not others. When this happens the tariff might be partially avoided through trade being rerouted to a third country, which can happen both “artificially” (when the third country is just a stop that allows the point of origin for the trade to get relabeled), or “naturally” (when trade patterns genuinely shift). If Mexican imports were tariffed, for instance, it is possible that U.S. consumers would find it cheaper to purchase those same goods from Germany, while countries that used to get those imports from Germany might now get them from Mexico. This would lead the effective cost of the tariff not to be the tariff rate itself, but the additional transportation cost from trade patterns changing. As a result, the net impact on imports might be substantially smaller.

2. The tariffed imports are so important and so hard to substitute that demand for them is basically price insensitive.

Frankly, this isn’t the case for Mexico; the goods they export are not, in general, irreplaceable and essential. But it would be the case, for instance, with Taiwan. The major export from Taiwan to the U.S. (and the rest of the world) is semiconductors, (6) and these are hard to source from anywhere else considering Taiwan’s semiconductors market share of 60% (90% for advanced chips). Without semiconductors you cannot make smartphones, you cannot run data centers, you cannot build cars, and most of your machinery – from radar to MRIs – will not work. Modern civilization is so reliant on semiconductors – and Taiwan is so important for their manufacturing – that it is highly unlikely that tariffs would meaningfully disturb the demand for Taiwanese imports, and in effect, for Taiwanese dollars. The corollary being that the exchange rate between U.S. and Taiwanese dollars should be close to unaffected by a unilateral tariff, with the brunt of its impact borne instead by American consumers.

3. The tariffs lead to retaliation, either because foreign governments formally retaliate with import tariffs or because foreign consumers feel aggrieved and decide to boycott exports.

Most (all?) countries that the U.S. has thus far placed tariffs on have either retaliated or promised to retaliate. On price alone we can therefore expect interest in U.S. exports to decline. The uncertainty around how reliable the U.S. will be as a trading partner going forward and the anger over the country’s perceived betrayal of its alliances certainly won’t help, especially if the trade war plunges former allies – such as Mexico and Canada – into a U.S.-induced recession.

4. Poor economic policies – of which tariffs are a striking example – make domestic assets less attractive to foreign and domestic investors alike.

Emerging market assets historically trade at something of a discount for a simple reason: government policy is often volatile and occasionally insane. Whether you are the bondholder of a sovereign or the shareholder of a corporation, governmental insanity tends to increase the probability that your future cashflows won’t be worth quite as much as you had originally thought, and the price of the assets responsible for those cashflows will have to reflect that. In the last half-century, the U.S. has benefitted from being a bastion of (relative) stability and its financial assets have consequently been accorded privileged status. If investors start viewing U.S. assets as exposed to erratic policymaking they will cancel this privilege, lowering overall demand for dollar-denominated assets.

The Trump administration seems intent on tariffing the majority, if not all, of its trading partners. If it does enact broad and universal tariffs, there will be very little trade rerouting, (7) and imports will indeed be hit with the full force of stated tariffs. In the idealized case where no government retaliates, no consumer spurns U.S. exports, and investor asset preferences are undisturbed by fatuous policymaking, we estimate that the U.S. dollar should appreciate by roughly one third of the tariff (e.g., 8% for a 25% tariff) versus a trade-weighted basket. This appreciation should be enough to bring dollar supply and demand back into balance as it increases the attractiveness of imports – where goods are still more expensive than pre-tariffs, but services (which are not tariffed) are cheaper – and decreases the attractiveness of U.S. exports (because a stronger dollar means those goods are more expensive for foreigners).

If we take it as granted that there will be retaliation but posit that investor preferences won’t change in the short run, which sounds somewhat more plausible, then the upward pressure on the U.S. dollar should be more muted. This is simply because when U.S. exports are tariffed in retaliation, demand for U.S. goods should decline. Given that the U.S. runs a trade deficit, this decline is still larger for imports than it is for exports if exchange rates don’t adjust. To make the declines equal and to keep net trade unchanged, the dollar still needs to strengthen somewhat. Our mathematical heuristic for any currency’s depreciation against the U.S. dollar under these circumstances – and we promise this is the only formula you’ll see in this letter – is:

where τ is the tariff, w _ US is the non-U.S. trade share, and the trade balance is exports minus imports from the point of view of the currency we’re evaluating. (8)

The heuristic says that depreciation increases with:

- The size of the tariff,

- The size of the U.S. goods trade deficit relative to total U.S. trade, and

- The size of the country’s trade surplus with the U.S. relative to its total trade.

This means the dollar should appreciate against almost all currencies, and that the first order determinant of that depreciation is the size of the U.S. goods trade deficit (as of 2024, 15% of the country’s total trade in goods and services).

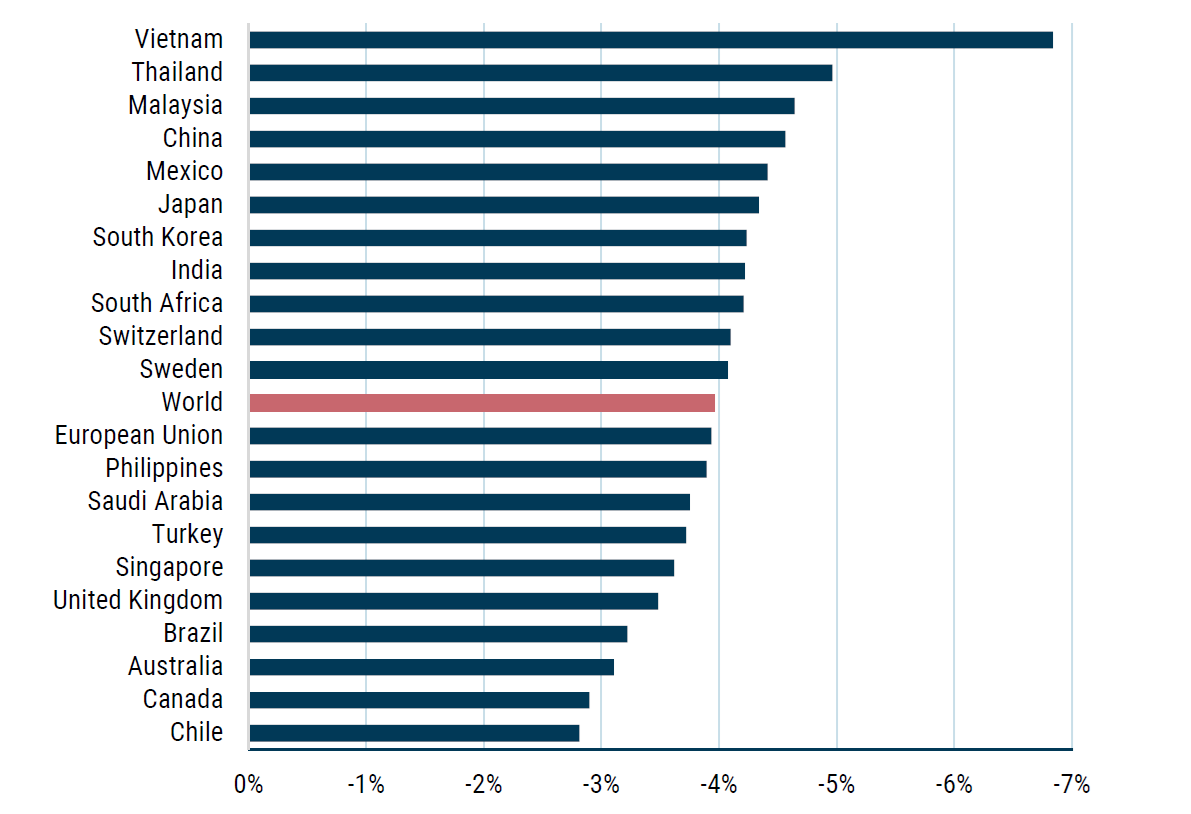

Only countries that run big trade surpluses with the U.S. relative to their total trade – think Vietnam, Mexico, and Eastern Asian economies – should see more pronounced levels of currency weakening. (9) Exhibit 1 makes this low currency dispersion clear:

Exhibit 1: Depreciation against USD (with retaliation)

As of 12/31/2023. Sources: World Bank, U.S. Census Bureau, Factset, GMO

The impact of tariffs on exchange rates is subject to the exact policies that get enacted. In the short run, if the U.S. unilaterally imposes substantive universal tariffs (say 25%), the dollar will appreciate meaningfully (8%). If retaliation occurs, the dollar will still appreciate, but by roughly half the original amount (around 4%). A longer-run threat to dollar strength is investor interest in dollar-denominated assets. If U.S. government actions decrease the attractiveness of U.S. assets to foreign (and domestic) investors, any short-run strengthening might well turn into substantial – and harmful – dollar weakening.

U.S. companies are in the line of fire

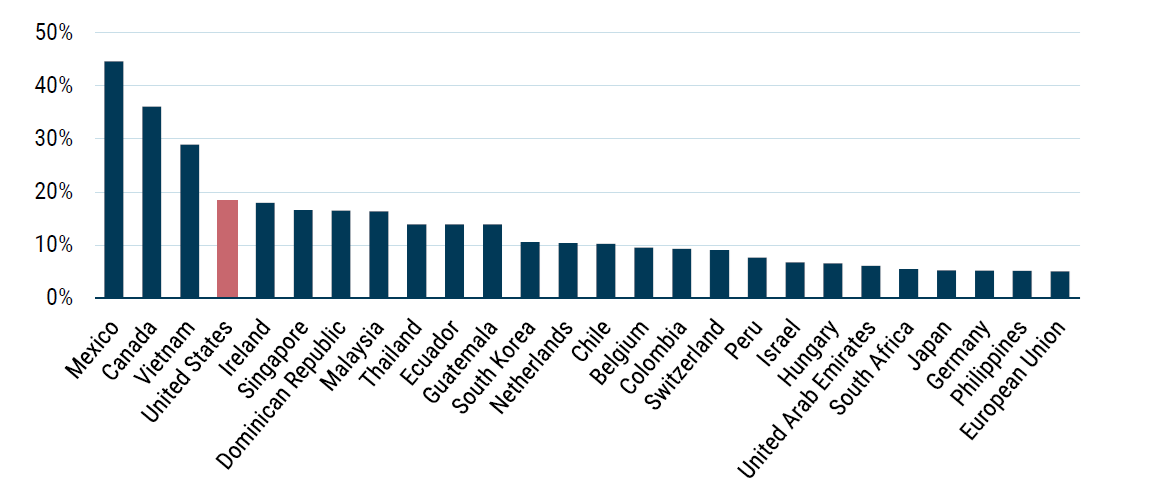

U.S. exceptionalism often has us assuming that an American-made trade war would be worse for the world than it would be for America. It begs reminding that U.S. trade is of much larger relevance for the U.S. economy than it is for the economy of most other countries in the world. Under broad 25% tariffs, we should expect extreme shocks to the GDP of Canada and Mexico (5% and 7%, respectively). We should also expect a very unpleasant jolt to the U.S. economy (of over 2% of GDP), where intermediate goods (like steel) will become more expensive, and export-driven industries take it on the chin. Exhibit 2 – which looks at total goods trade with the U.S. as a percentage of GDP – shows that the U.S. is 3-4 times more exposed than most of its trading partners.

Exhibit 2: U.S. goods trade (% of country's GDP)

As of 12/31/2023. Sources: World Bank, US Census Bureau, Factset, GMO

The threat of tariffs is a threat to stocks, and the chart above shows us that American equities are very much in the line of fire. If a company’s manufacturing occurs outside the U.S. but its sales are U.S.-centric – as they are for Apple – that is a problem. If a company imports intermediate goods for its production – as happens with GM – that is also a problem. If a company’s expansion plans involve lots of imports – true for everyone expanding cloud and AI capabilities – that is, again, a problem.

If we are interested in assessing how tariffs will affect a company’s fair value, there are two questions that govern our concerns:

- Is this company likely to suffer a permanent drop in its profits relative to what we had otherwise penciled in?

- If a recession takes hold because of tariffs, will this drop in profits be sufficiently acute to make this business go bankrupt?

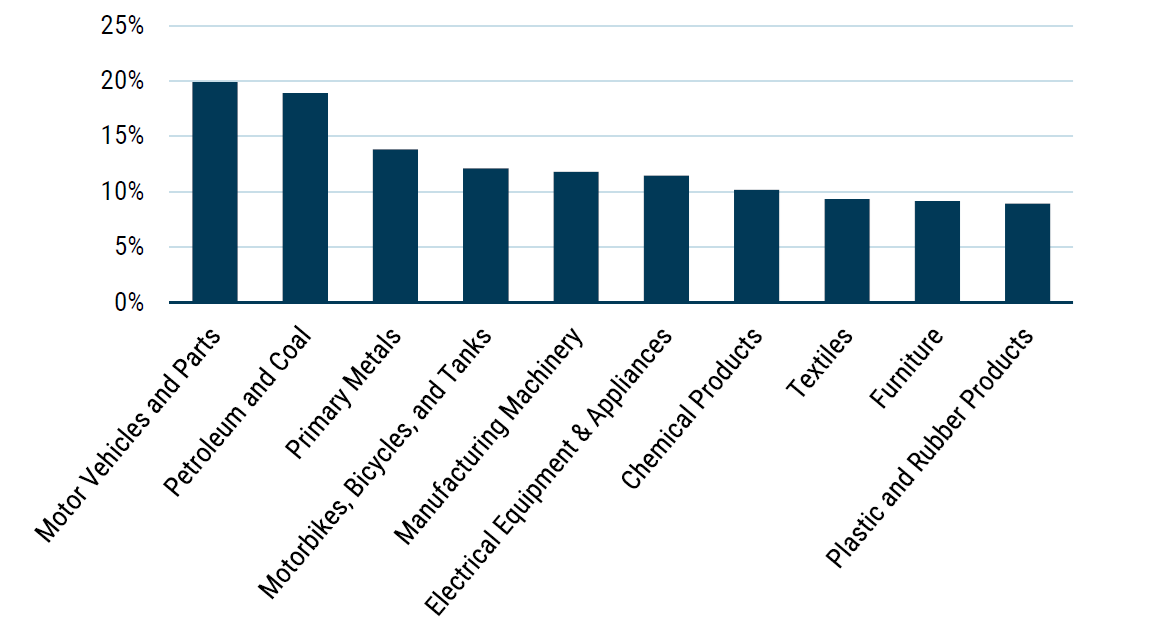

Let’s start with question #1. Tariffs directly impact American companies by raising their costs when they import intermediate goods or outsource production. Retaliatory tariffs, in turn, raise the prices of exports. In either case American companies face higher implicit costs, which they can either absorb (to preserve sales) or pass on to consumers (to preserve margins). While their exact choice depends on how price sensitive demand is for the product they produce, in the short-term we should expect consumers to absorb about 80% of the tariff (through price increases) and producers to absorb the rest, leading to both lower sales and lower profit margins. (10) Exhibit 3 shows the top 10 industries where import costs are a high percentage of gross output.

Exhibit 3: Top 10 industries by import costs (% of 2023 gross output)

As of 12/31/2023 | Sources: Worldscope, Compustat, MSCI, S&P Global, GMO

Our production of cars, trucks, energy, bikes, tanks, hardware (hi, Apple!), and rubber products are all in the direct crosshairs of tariffs. As costs for companies in these industries rise, they will have a shortfall in profits as they both produce fewer goods and sell them at a lower profit margin. The long run, however, paints a slightly more nuanced picture.

In a highly competitive market, tariffs – much as any tax – will eventually be fully absorbed by consumers. If an industry has free entry and exits, companies should earn enough profit to compensate their employees and stakeholders but receive no excess profit beyond that. (11) If profits are very high, entrepreneurs will be incented to go into that industry; if losses are being accrued, labor and capital we be incented to go elsewhere. This means that the short-term pain faced in highly competitive industries will eventually dissipate, though in the process an industry’s “losers” will go out of business (e.g., retail through the Pandemic).

In an oligopolistic market, a description that befits most U.S. large caps, it is harder to see this dissipation happening quickly. Because companies in oligopolistic industries do earn excess profits beyond what is necessary to pay their stakeholders, a dent to those profits does not engender any exits from the industry.

While a well-run monopoly is unlikely to face bankruptcy because of tariffs, it is almost certainly going to face a prolonged hit to its bottom line.

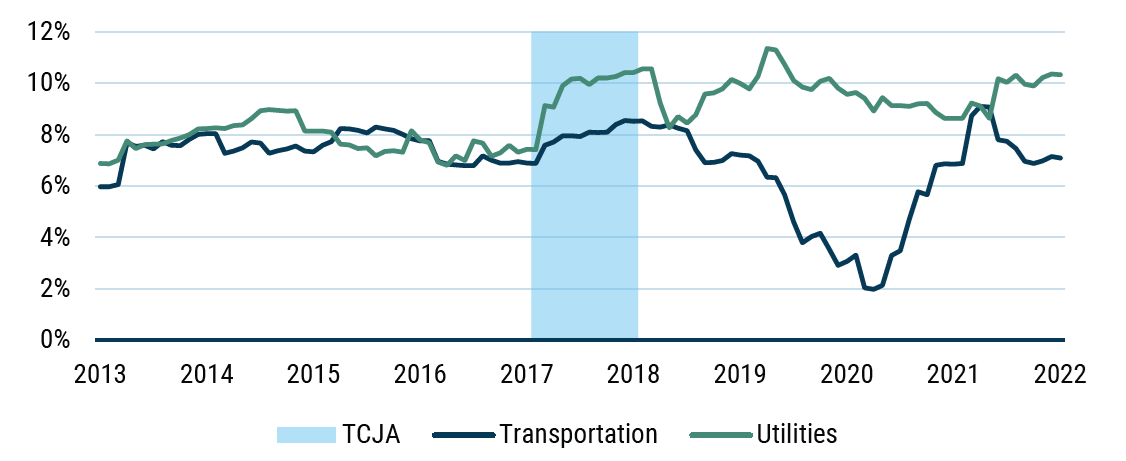

This dynamic between competitive and concentrated industries is easy to see if we contrast transportation and utilities companies in the aftermath of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (see Exhibit 4). The initial reaction for both industries was an upswing in profits. But transportation companies, as a result of their industry structure, quickly saw margins come back to normal levels. This reversion to “normal” profit margins simply didn’t occur with utilities, where the blend of regulation and the cost to entry make new competitors fairly uncommon. (12)

Exhibit 4: Utilities & transportation profit margins

As of 2/28/2025 | Sources: Worldscope, Compustat, MSCI, S&P Global, GMO

It is easy to conflate monopolies with businesses that will win in any type of market environment, but this simply cannot be true. While certain characteristics of monopolies are consistently underappreciated by investors and potentially incorrectly priced – good management, for instance – monopolies are not intrinsic outperformers whenever the economic landscape changes. The same mechanism that makes these companies quasi-permanent beneficiaries of tax cuts makes them equally vulnerable to tax increases. This makes companies that are both exposed to higher tariffs and that benefit from being in oligopolistic industries (hi again, Apple!) particularly vulnerable to an all-out trade war.

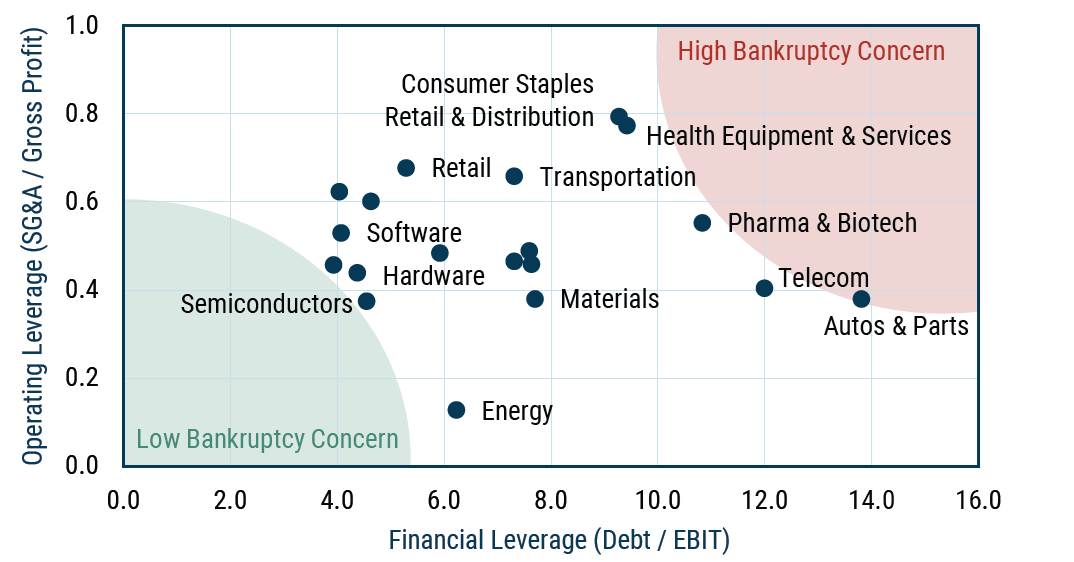

Though permanently lower profits are a real concern, the most acute source of pain for the shareholders of a business is bankruptcy. Bankruptcy, after all, is equivalent to zero profit forever. In previous work we have spoken about how to identify businesses with high bankruptcy risk. (13) Companies that have high operating leverage – those whose fixed costs are a large portion of their cost base – will likely be cashflow constrained in the event of a recession. If those companies also happen to be financially levered prior to a recession, they are probably going to have a tough time raising external financing and will therefore be particularly exposed to an equity wipeout. Exhibit 5 contrasts GICS industry groups on their operating and financial leverage, showing that the greatest areas for investor concern are autos (on the financial side) and consumer staples retail & distribution (on the fixed costs side).

Exhibit 5 - Industry leverage

As of 2/28/2025 | Sources: Worldscope, Compustat, MSCI, S&P Global, GMO

Not all U.S. equities will be hurt by tariffs, whether they are unilateral or not. American companies that manufacture their goods locally and face competition primarily from abroad – say, U.S. Steel – should indeed benefit. But these companies are relatively few and far between, and the combined impact of tariffs, a stronger dollar, and weaker consumption is a net negative for the average U.S. stock. Tariff risk, piled on top of the notoriously high valuations of U.S. companies, makes the American stock market a hard pitch. And yet you could do worse. All you would have to do is buy some U.S. corporate credit.

Credit spreads are not pricing in enough bankruptcy risk

If you buy a bond with the intent of holding it to maturity, the best thing that can happen is for you to receive the agreed-upon coupons alongside the bond’s principal. (14) The worst thing that can happen is for your money to disappear in a recovery-less default. When asset allocators analyze different parts of the credit market, the question they should be asking themselves is whether the spreads on offer are sufficient to compensate them for the default risk they are taking.

Today’s spreads are tight. This is especially true of U.S. high yield, where spreads are trading at the 15th percentile. High-yielding companies are typically businesses that have high operating and financial leverage, and they often carry plenty of loans that are senior to the unsecured credit bought in secondary markets. In a world with heightened uncertainty – and it is hard to argue that the new administration is making life more placid – the prospect of bankruptcies and defaults for these companies should be on the rise.

At current spreads (or anything close to them), our advice is simple: avoid U.S. high yield credit.

Conclusion

There is a lot we still don’t know about how U.S. trade policy will evolve in the coming months. One thing is clear though. While rising tariffs have not been a meaningful risk for U.S. (or most global) investors for more than a half century, they certainly are today. But risk is not certainty, and the impacts of various potential paths and policies would be quite different. What we have therefore tried to do is build a toolkit to help us and our clients understand what assets are particularly vulnerable if tariffs come in, and why. In the case of currencies, a lot of what we found was pretty intuitive. Tariffs increase the fair value of the U.S. dollar, and the extent of that appreciation versus another currency depends on how much of that country’s trade is with the U.S. and how large a trade surplus it has with the U.S. If the U.S. imposes a tariff on imports from Mexico, the Mexican peso should depreciate relative to the U.S. dollar, and it is much more vulnerable than most other currencies to a hit from tariffs. What was a little more surprising to us was realizing that the U.S. imposing a universal tariff on imports would be worse for the peso than a tariff that was specific to Mexico. (15)

Within equities, there are some obvious losers and some slightly less obvious ones. In broad brush terms, we can expect tariffs to initially impact both sales and profit margins as prices rise by a portion of the tariff but less than 100%. In a fully competitive situation, those prices will eventually adjust fully as the weakest players are forced to either shrink or go out of business and industry-wide profit margins revert to normal, albeit at lower sales volumes. In oligopolistic situations, the price impact will be less than 100% in the longer run and both sales and profit margins will be permanently reduced (at least insofar as the tariffs are permanent). That means weak companies are at higher risk of bankruptcy, but even high-quality companies lose some expected future profits. This is true of all companies that have significant goods sales in the U.S., whether U.S.-based or not.

For corporate credit, the math is even simpler. Tariffs should be expected to weaken both the global and U.S. economy and will have substantially varying impacts across individual issuers. In aggregate it is hard to see how tariffs would have anything but a negative net impact for low-quality corporate borrowers, since investors won’t get much benefit from the fairly rare tariff winners and risk significant losses from the wider array of losers.

We have been pleased by the strong relative and absolute performance of GMO’s Asset Allocation strategies in the first quarter. While we did not particularly position the portfolios for the imposition of tariffs, the result does demonstrate the potential for valuation-sensitive strategies to add value in times of heighted uncertainty. As we look forward from here, our focus is on building diversified portfolios of assets that offer decent risk/reward trade-offs given the current uncertainties. Unfortunately, there are very few equities that are truly immune to a U.S. attempt to unravel global trade. Even the Magnificent Seven stocks, which have seemed impervious to all else over the past decade, stand to lose something given that their very market power and enviably fat margins create vulnerabilities when their costs of production rise. The problems for junkier companies seem significantly scarier, however. Such companies are always more at risk should a recession strike, and layering in the cost and sales risks coming more directly from tariffs compounds the problem. Generally, we see that equity investors are getting paid more for taking risk outside of the U.S. than inside the U.S. and much more in value stocks than in growth.

As we see it, U.S. companies have at least as much at risk as non-U.S. ones from U.S. tariffs, so we don’t see a reason to retreat from our non-U.S. versus U.S. bet on those grounds.

Within value, our concern is about the downside risk of the junkier and more levered end of the group. We generally prefer to bias ourselves away from those companies due to their recession risk, and we consider that even more sensible given the enhanced downside risks that tariffs create. On the other hand, there will almost certainly come a time when those risky stocks will be exactly the ones to own — when investors are pricing in truly terrible outcomes, a diversified portfolio of desperately cheap junky stocks becomes a good risk/reward trade-off. We don’t think we are there yet, but if the junky stocks substantially underperform the rest of value from here, we could get there. Within bonds, we see little argument for owning high yield corporate credit today. Even in the absence of the risks that come along with tariffs, we’d have said that spreads are decidedly unimpressive and bond prices are high. Layering in the added risks of tariffs seems to make for a particularly poor risk/reward trade-off. Government bonds are far from risk-free in an environment where inflation is a meaningful risk, but they look to be a much better bet than corporates.