Term deposit rates are high and risk-free. So why own bonds?

Fixed income has traditionally served as the first line of defence against volatility. In 2022, it took a leave of absence from the job.

The S&P U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, which tracks the performance of publicly issues U.S. debt, returned -12.03%.

While the growth outlook may not have improved since then, the inflation outlook has. This is good news for bonds in terms of yield, total return, and their diversification benefit.

But with term deposit rates up near the 5% mark, is fixed income as attractive as it once was? And to what extent does it live up to its role as the core defensive allocation within a portfolio?

To help answer those questions, this wire will draw on the views of Kerry Craig, Global Market Strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management, and Myles Bradshaw, Head of Global Aggregate Fixed Income strategies at JPMorgan Asset Management.

How restrictive are interest rates?

To understand how fixed income assets will behave from here, one needs to understand the outlook for rates.

Many factors feed into this, but here are some of the most important.

Recession risk

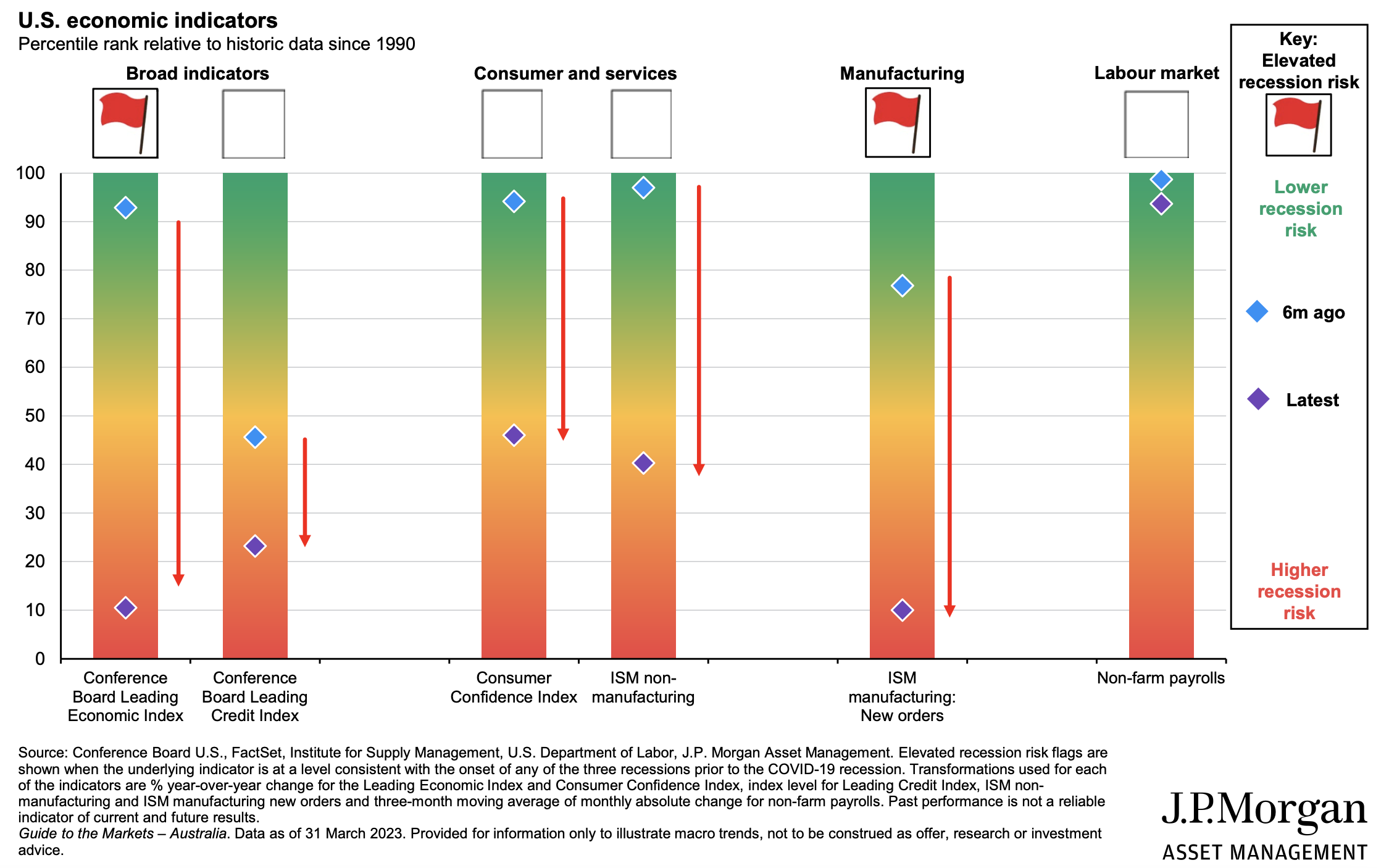

JPMorgan have compiled a heat-map for economic recession risk based on the below categories, broadly split into broad indicators, consumer and services, manufacturing, and the labour market.

As of the end of March, the heat map showed the most concerning deterioration across The Conference Board Leading Economic Index and the ISM Manufacturing survey. The labour market is also slowing despite a rise in April's non-farm payrolls.

"Our base case is you're more likely to get a recession this year - at least a quarter of negative growth in the fourth quarter and then probably one the next quarter in 2024," says Craig.

Inflation

If rates have increased sufficiently to curb inflation, then a pause and indeed rate cuts become more likely.

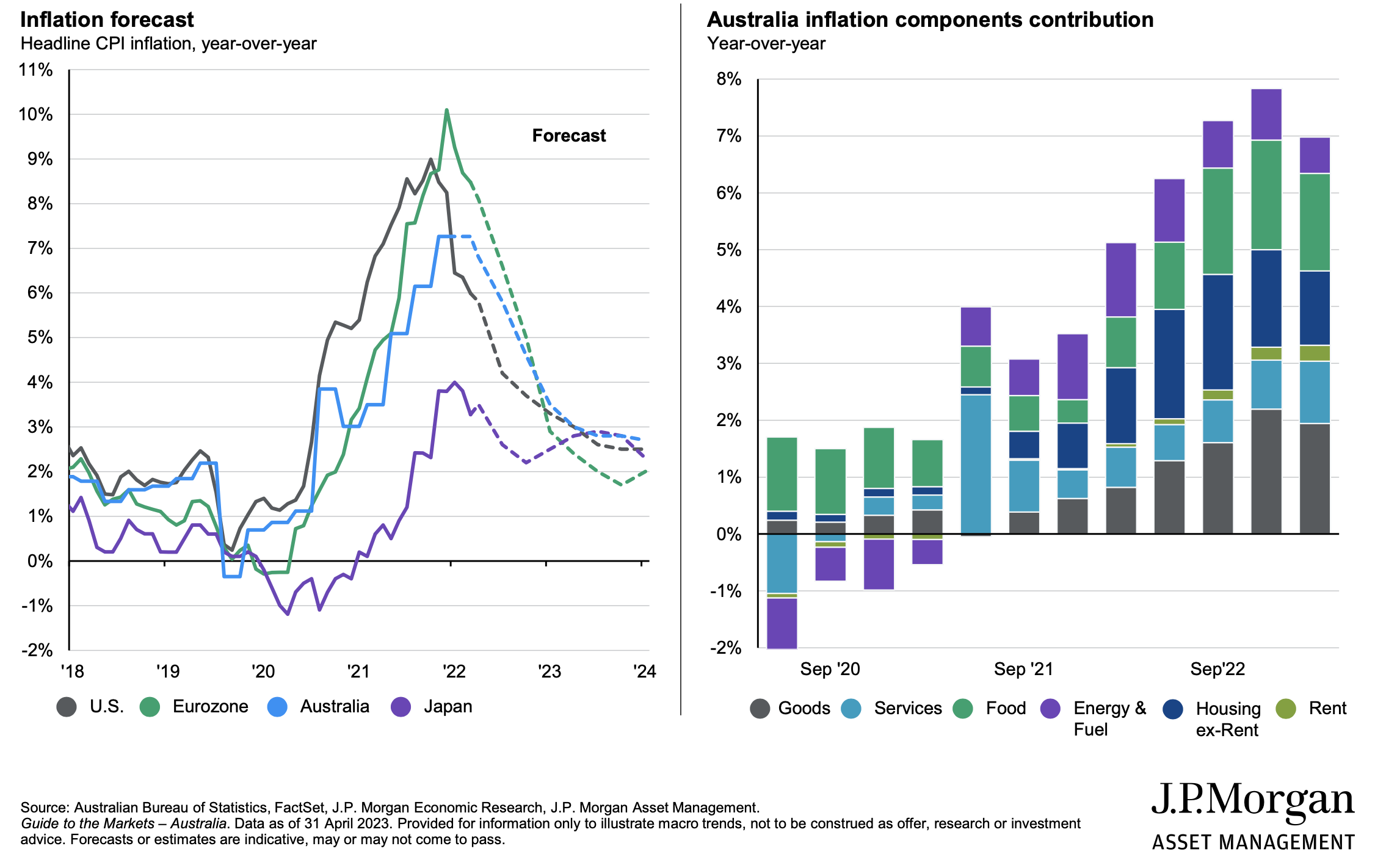

Of course, weaker growth would intuitively portend a fall in inflation, and here the outlook is promising.

"We're seeing energy prices negative year on year, food prices have collapsed, core goods inflation has collapsed, shelter is a lagging indicator and it's returned to pre-COVID levels. That leaves core-services ex-shelter, and that's remained stubbornly high," says Bradshaw.

"It's coming down but not enough for the Fed to declare victory."

"Whether it's the US, Eurozone or Australia, the inflation outlook has come down as growth slows," adds Craig.

The US is further along that road due to earlier and more aggressive rate hikes.

Importantly, though, inflation still remains well above central bank targets.

"The fact it remains sticky pushes back on the idea of rate cuts from central banks this year," says Craig.

Banking crisis and liquidity

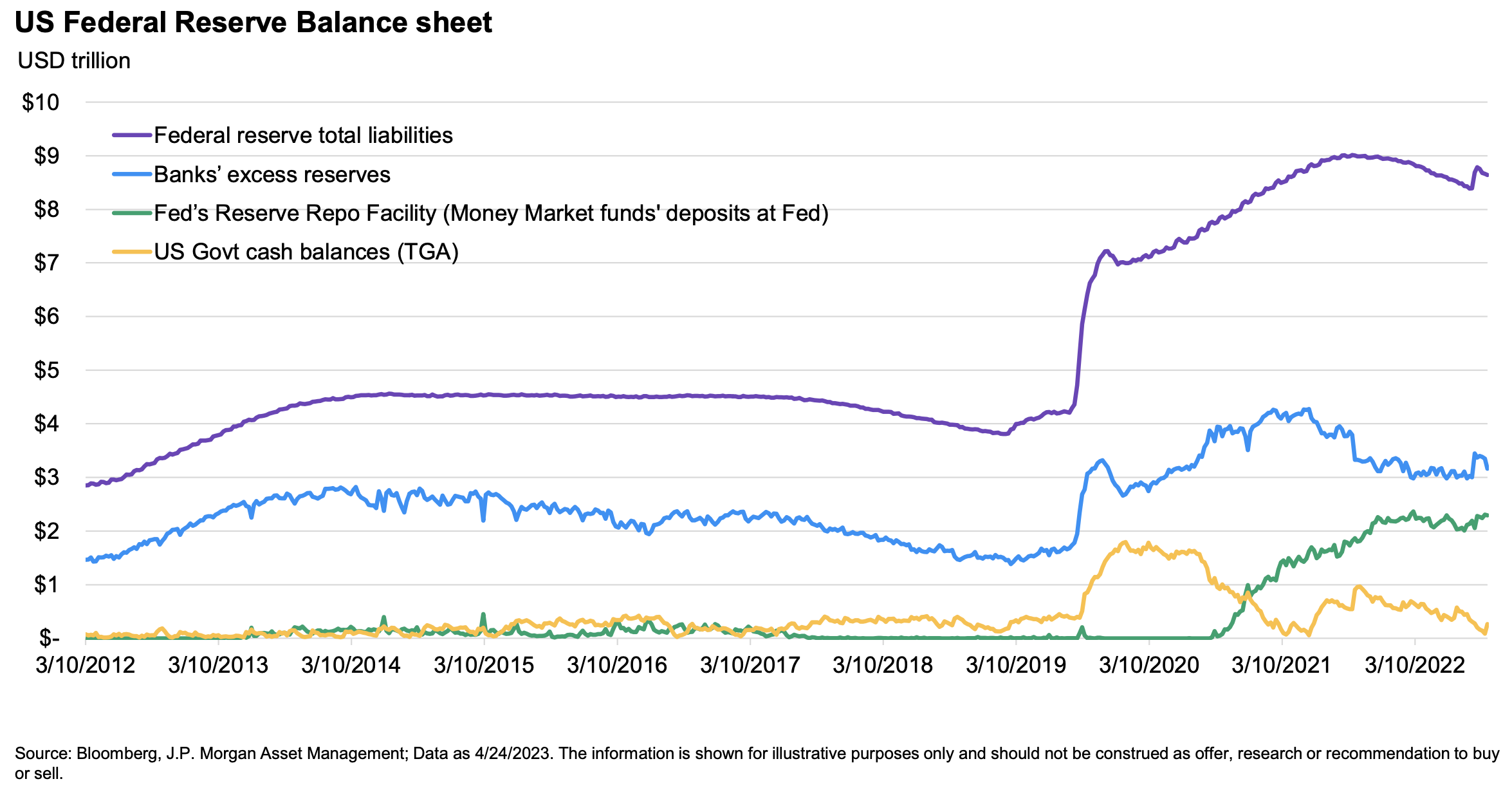

In simple terms, monetary tightening via rate hikes and quantitative tightening (shrinking the Federal Reserve's balance sheet) is an exercise in pulling liquidity from the market.

The Fed is shrinking its balance sheet by between US$65-90 billion a month, notwithstanding the US$500 billion it put into the market to save Silicon Valley Bank.

The blue line, meanwhile, represents the excess reserves banks have deposited with the Fed.

"That's the key input in terms of money going into the economy, in terms of credit creation, and in terms of risk-taking," says Bradshaw, "and that's been coming down."

The problem as it relates to the banking crisis is the distribution of these returns, with the big four banks commanding about 75% of these reserves.

"Although this level is higher than it was in 2019, the reserves are not uniformly distributed, and the banks that are more vulnerable are starting to suffer. And that's where we have this regional banking crisis."

The money that's been pulled from the banks has found a home in money markets, represented in yellow, somewhat neutralising the affect of the Fed's effort to shrink its balance sheet.

But aside from the money moving into the money market, liquidity is being sucked from the economy.

"This squeezing of liquidity is going to continue to tighten conditions in the economy in a way that the heightened Fed Funds rates were doing last year," says Bradshaw.

All told, the reduction in liquidity sloshing around the market crimps growth and thus ease pressure on the Fed to maintain rates at a restrictive level.

Inflation, the enemy of fixed income diversification

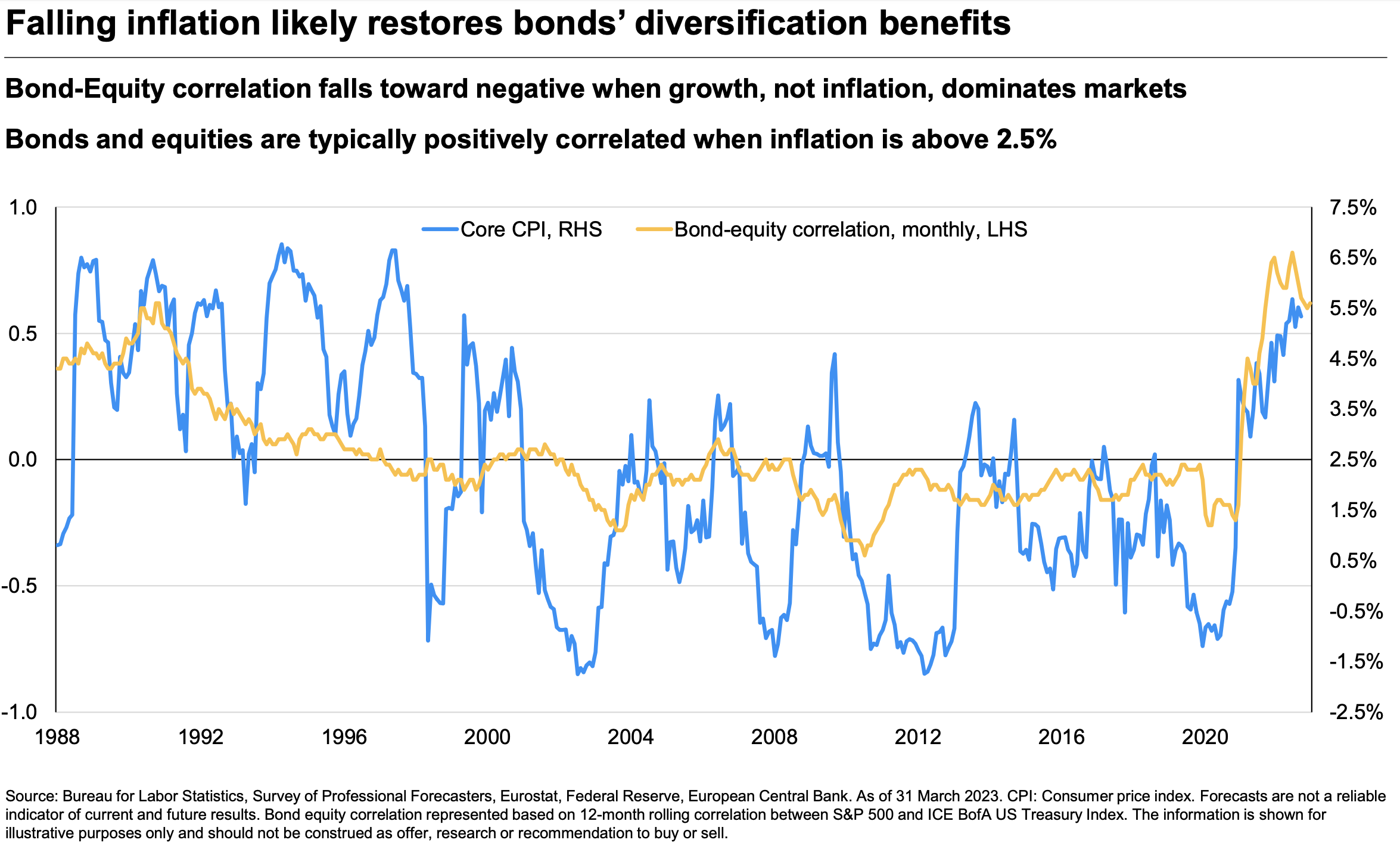

Traditionally, bonds have provided investors with return but also diversification thanks to an inverse correlation to equities.

Inflation, though, has laid waste to that negative correlation.

The yellow line in the chart below shows inflation in blue and the rolling correlation between bonds and equities in yellow.

"2022 was horrendous, not just because bond prices were going down, but because they were going down with everything," says Bradshaw.

The correlation tends to be negative with core CPI is below 2.5%.

"This is intuitive and easy to understand," explains Bradshaw.

"If inflation is high, the Fed is raising rates to kill inflation. And that means bond yields go up. It also means that the discount factor for equities goes up, so the price goes down. And the growth assumption goes down.

But when inflation is below 2.5%, central bank can respond to weaker growth by cutting interest rates, and that's where you get your negative correlation."

Now inflation is rolling over, precipitating a return to the negative correlation we all know and love.

"With the outlook for inflation coming down, it supports the argument that you're going to get diversification for investing in bonds."

Diversify with investment grade

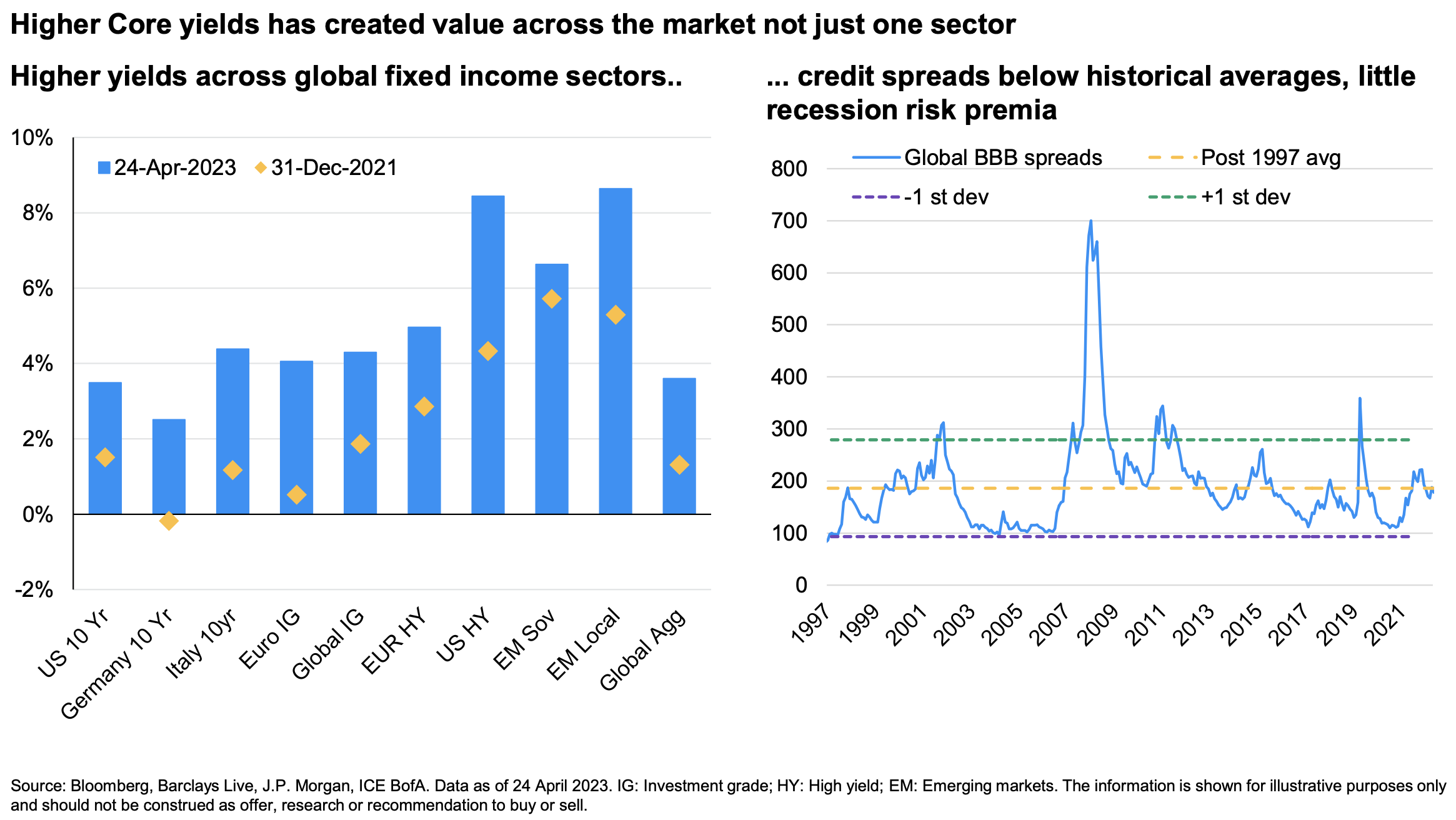

Fixed income yields are trading higher across all sectors, compared to December 2021, and these higher core yields have driven higher returns overall.

You can see that on the below graph, where triple-B credit spreads are trading at their long-term average.

However, return should only be understood in the context of the risk taken for it. And here, investment grade is the way to go.

"You're rewarded for buying a diversifying core bond fund so you're not taking a sector bet," says Bradshaw. "[But] you're not rewarded for going for risk in areas like high yield."

Term deposits vs fixed income

Risk-free term deposits are currently paying out upwards of 4.5% in Australia. That still equates to a negative real return of a few percentage points given Aussie CPI is running at 7%, but it's nonetheless attractive in a volatile market.

But term deposits don't offer capital growth. You get the yield and that's it.

Bonds, on the other hand, offer an absolute return encompassing yield and capital growth (if sold before term).

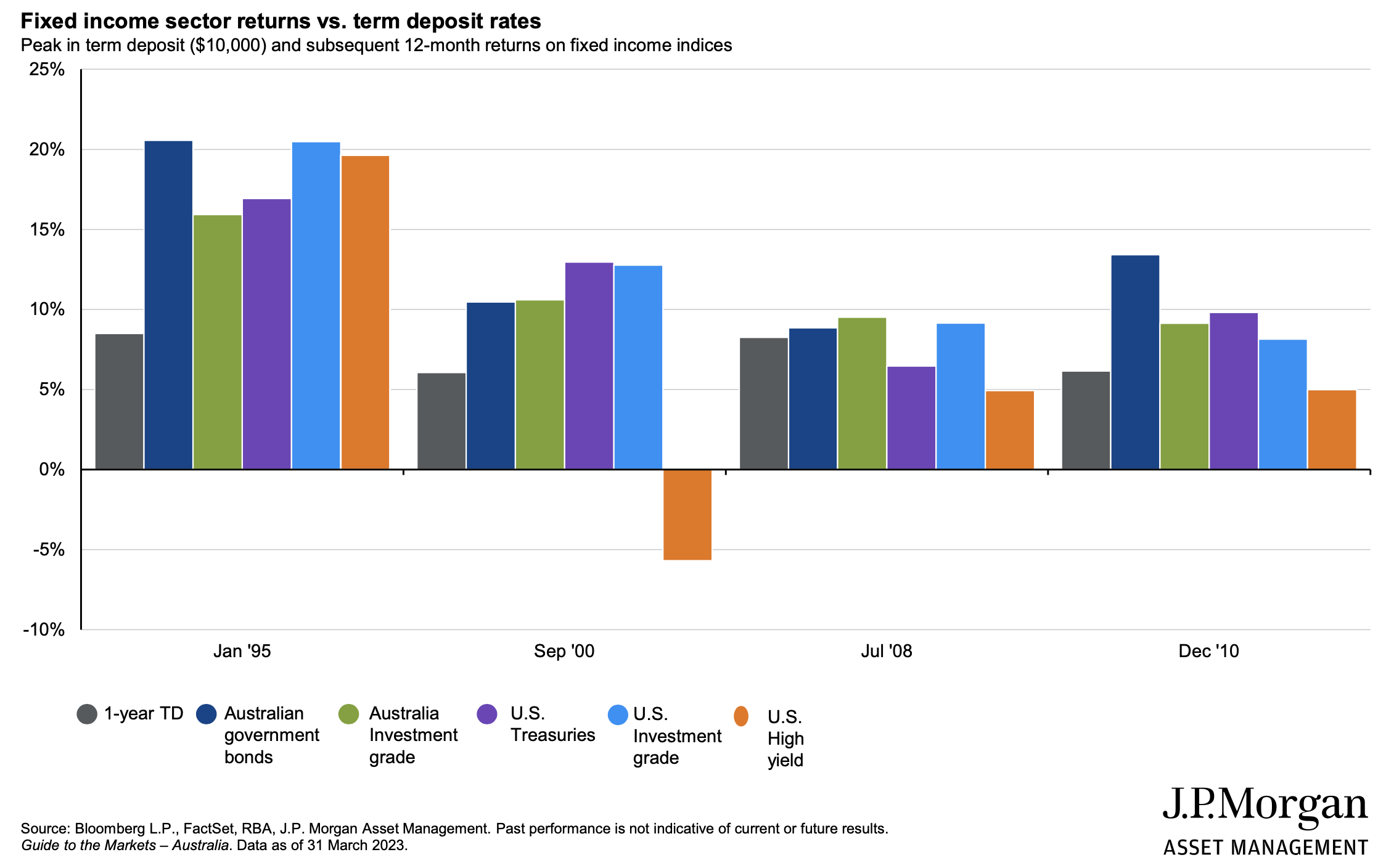

And if the chart below is anything to go by, absolute return from fixed income beats out term deposits once interest rates peak.

Namely, all fixed income sectors (with the exception of U.S. high yield at the turn of the century) massively outperformed term deposits in the 12 months after the latter peak.

Across the sectors, anything above investment grade, both here and in the US, has outperformed term deposit rates by over 5% since 1995.

2 topics

1 contributor mentioned