That '70s disaster: Central banks will have to work harder than ever to control inflation

I grew up in the 1970s and it was fun – Abba, Elvis, Wings, JPY, flares, and cool cars. But economically it was a mess. Inflation surged and so did unemployment and it was bad for investors too.

After years of economic pain, voters turned to economically rationalist political leaders – like Thatcher, Reagan, and Keating to fix it up. Their policies to boost productivity ultimately culminated in the independent inflation targeting system that central banks now use. Along with the help of globalisation, more competitive workforces, and the IT revolution - inflation finally got under control in the 1980s and 1990s.

But the experience of the last year when inflation has surged tells us that unlike the parrot in Monty Python it really wasn’t dead but just resting.

In this wire, I argue why central banks will have to work harder than ever to control inflation. And for all those calls about wage-price spirals being a "baby boomer fantasy", I'll share why I think the experience will suggest otherwise.

But first, a history lesson

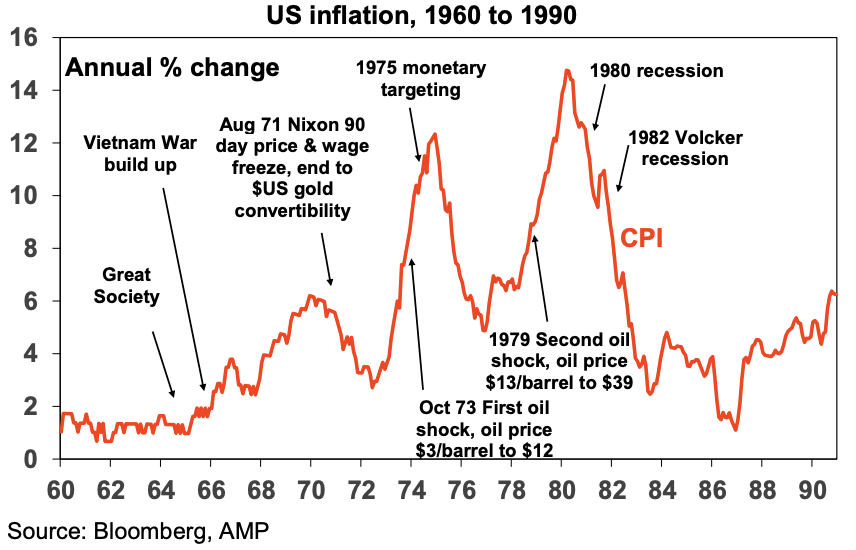

Many associated the inflation of the 1970s with the oil shocks of

1973 and 1979 but it actually got underway before that - as this chart shows:

A combination of these factors created an environment where inflation tripled in America in just four years:

- A big expansion in the size of government and welfare.

- Disruption associated with the Vietnam War.

- Tight labour markets (with unemployment falling to 3.4% in 1969 in the US and spending most of the 1960s below 2% in Australia) led to more militant workers and surging wages.

- Easy monetary policies supported high inflation.

- Social unrest & industry protection also played a role

Contrary to popular opinion, come 1973, inflation had already increased to

8% before the OPEC shock. The same whipsaw happened

after another recession in 1974-75 which saw inflation bottom

out above its previous high only to take off again. The process

only ended with the deep recessions of the early 1980s.

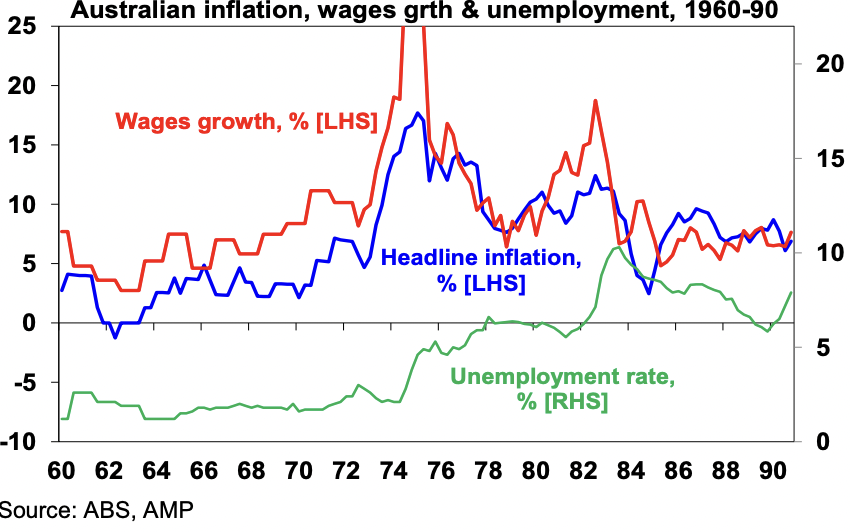

It was pretty much the same story in Australia, although here it

started more in the early 1970s and was made worse by 20%

plus wages growth and massive fiscal stimulus in 1974. This chart below shows the Australian experience:

The end result was a decade of high inflation and high

unemployment. The problem was that policymakers were too

slow to realise the extent of the inflation problem initially and

then were too quick to ease which enabled inflation to quickly

pick up again and move higher. The longer inflation persisted

the more inflation expectations rose – with wage growth rising –

making it harder to get inflation back down.

Does this all sound eerily familiar?

There are several reasons for concern about a return to the sustained high inflation of the 1970s today:

- Labour markets are very tight once again. Wage growth in the US has already increased to around 5%.

- Demand has been strong - suggesting that the problem is not just due to supply disruptions.

- We are seeing a run of supply shocks – with notably the war in Ukraine, another energy crisis & repeated floods locally.

- Government policy has swung away from the economic rationalist approaches of the 1980s – with more tolerance for bigger more interventionist government – as median voters have swung back to the left.

- The globalisation that followed the end of the USSR and trade with China is under threat and appears to be reversing, not helped by a desire for onshore supply chains.

- This is being reinforced by geopolitical tensions which are boosting defence spending which adds to metal demand.

- Decarbonisation will boost near-term costs & metal demand.

- The ratio of workers to consumers is falling and the entrance of millennials to the workforce replacing retiring baby boomers will depress productivity

- Policy makers were caught focussing on the last war of disinflation coming out of the pandemic just as they were in the 1960s when the big fear was a return to 1930s deflation. This saw massive fiscal stimulus and money supply growth.

- Inflation is now very high at around 9% in the US, Europe, and UK. It's an estimated 6% in Australia.

As we saw in the 1970s, the longer it remains high the more businesses and workers will expect it to remain high and they will plan accordingly. When inflation expectations move up, that will make it harder to get inflation back down.

Why high inflation is bad for investors

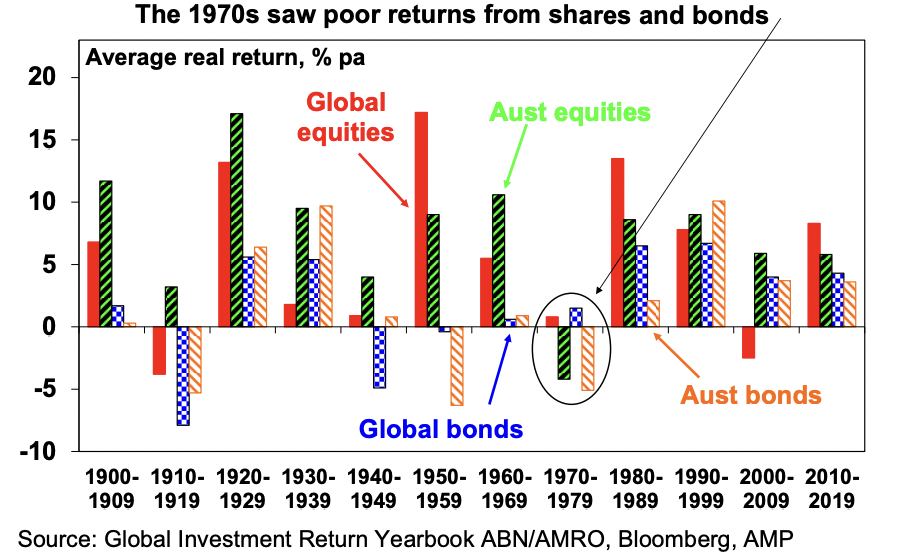

The 1970s experience warns it is in investors' long term interests to get inflation under control (even if it means short term pain). For investment markets, high inflation is bad as it means:

- Higher interest rates – making cash more attractive and other assets relatively less attractive.

- Higher economic volatility and uncertainty – a period of multiple recessions means that investors will demand a higher risk premium to invest.

- For shares, a reduced quality of earnings as firms tend to understate depreciation when inflation is high (this tends to unfold gradually).

It means that the boost to earnings (or say rents in the case of property or infrastructure) from inflation tends to be offset by a negative valuation effect as investors demand lower PEs/higher yields. The bottom line is that a sustained period of high and rising inflation can be a problem for bonds, shares, and other growth assets.

As can be seen in the next chart, the high inflation

1970s was one of the few decades to see poor real (ie after

inflation) returns from bonds and shares.

Is there any reason why we won't see a 1970s scenario again?

While many of the structural forces that drove the disinflation of the last few decades are reversing and suggest higher inflation over the decade ahead than seen pre-pandemic, sustained 1970s style high inflation appears unlikely. Here's why:

- Central banks understand the problem and the need to keep inflation expectations down.

- While inflation is high, longer-term inflation expectations remain low and wage growth is still relatively low.

- Labour markets are far more competitive today with much lower levels of unionisation. In Australia, only 14.3% of employees (including me) are in a union. In 1976, it was at 51% of employees.

- Finally, there are signs of easing cyclical inflation pressure in the US & it's leading by about 6 months.

So, while inflation may not go back to pre-pandemic lows and the longer-term tailwind for investment markets from ever lower inflation and interest rates may be behind us, a full-on return to the 1970s malaise looks unlikely.

2 topics