The anatomy of Amazon’s success

Kasa Investment Partners

In the Darwinian world of capitalism, the capacity to design superior organising systems can be a powerful source of competitive advantage. For new phenomena to manifest we need motion. This motion can be inorganic such as the wind or fire, or it can be organic, such as a cat moving toward its feeding bowl or a person staying back late to finish a project. The primary purpose of a company’s organisational structure is to create the conditions for employee behaviour to align with the company’s objectives. Within Kasa’s investment framework, this type of advantage will likely lead a company to producing a steeper and more resilient cash flow profile than would otherwise be the case. In this note, we’ll learn how Amazon’s organisational structure provides it with such an advantage.

The most interesting aspect of an organism’s motion is the intelligence that drives it, the decisioning process. This is also the most important factor driving a company’s evolution – who is charged with making decisions and how do they make these decisions? Let’s assume Alice is a manager at Amazon and that Bob reports to her. Who is in a better position to decide if Bob should work on Project A or Project B? Will Bob be happier if Alice tells him to stay back and finish off a project, or would he prefer his performance indicators to guide him there silently? A useful place to start in answering these questions is to look at biological systems; we are biological beings, afterall.

Engineering a superior organism

Steve Grand has dedicated his life to exploring artificial consciousness, understanding the interrelationships between matter, life, mind and society – it turns out they are different aspects of the same phenomenon. In the mid 90s he developed a computer game that simulated a biological system using the most basic building blocks of life. Let’s take a peek into Grand’s (lightly edited) view of the world:

“You are actually a colony of single-celled animals. Over ninety percent of the cells that make you up aren’t even related to your parents. Bacteria happen to live in your gut, on your skin, and even in your mouth, yet you can’t live without them. But even the ten trillion human cells that are related to your parents are really just single celled animals that happen to be glued together by a sticky substance; and not always glued either – the white cells in your blood are just little amoebae swimming up and down your bloodstream eating bacteria. So they’re really quite independent little animals. And yet nobody’s in charge of these systems, there’s no CEO at the top, there’s not even a network manager desperately trying to avoid viruses by preventing everyone from installing games on their PCs. If a virus that can make the whole system fall over comes into our body, this huge complex system swings into operation and mops it up, without anyone there to give the command, and without us even being aware. And if our immune system didn’t work like crazy 24/7, we would rot in a week, like a dead body does.

One of the reasons for the way that natural systems are robust, and not brittle, is the direction of control. Cells don’t tell each other what to do, they just scan their local environment and react to change; this reaction itself then changes the environment. Another cell notices this change and responds. It’s completely localised and everybody’s disconnected from everyone else. Nature’s machines are self-organising; the study of biology is essentially the study of self-organisation.”

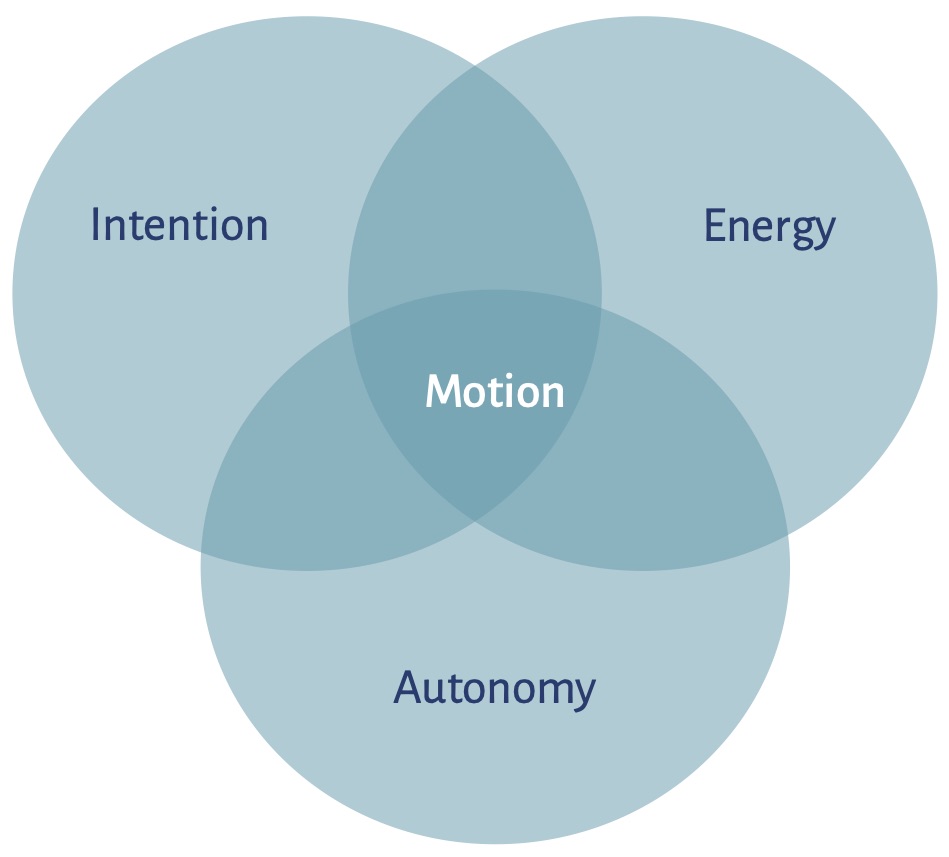

Any organism, be it a cell, a person, a team, or a company, needs three basic elements for motion. First, an intention or motivation, for example, organisms have an inherent will to survive. Second, some form of fuel to power the movement. Finally, the organism needs the freedom to move unencumbered, and autonomously. A feedback or reward mechanism that links the movement back to the initial intention can help perpetuate the motion.

One of Grand’s profound insights was that the resilience of natural systems was due to the direction of control being from the most basic building block up and not top-down. Put another way, biological systems are self-organising. If you want an organisation to move in a certain direction, instead of giving top-down directives, you should set up a system where the most basic units are motivated to move in the desired direction; provide those units with the energy and freedom to animate, then sit back and allow them to do their thing. We can break an organisation down to its businesses, the divisions in those businesses, the teams within those divisions, the people within those teams, the cells that make up those people and so on. The idea is to drill as far down as is practical and work there. In the mid 90s, Grand simulated this concept in a computer game called Creatures; and shared his views and insights in Creation, a book published in 2000.

Amazon’s founder and CEO, Jeff Bezos, read the book and set about re-engineering Amazon’s internal structure to resemble a self-organising system. Before turning to that, I’d like to share a little about my personal experience of working within a successful self-organising system. When I joined Fidelity in 2007, it was the most successful investment manager in the world, with around $2 trillion under management. I was very curious to find the secret sauce. Well, it turned out to be a very well-designed self-organising system.

Unlike most of its competitors, Fidelity did not prescribe an investment process – it instead empowered the most basic unit within the organisation: the investment professional. Let’s look at the three basic elements of motion within Fidelity’s investment team:

Motivation: the hiring process filtered for high achievers not comfortable with performing poorly. There were clearly defined performance metrics, which were carefully designed to align each individual’s incentives with the organisation’s goals.

Energy: there was what felt like an unlimited budget to spend on research, be it travelling, conducting surveys, calls with experts or compensating brokers. The constraint was almost always time, not money.

Freedom: each person had a high degree of autonomy, and was free to make investment decisions, as well as allocate resources and time as they saw fit.

Finally, there was a strong feedback loop between effort and outcome, with a highly variable remuneration structure that was tightly linked to the individual’s performance metrics. This led to significant experimentation at the individual level, with successful techniques being identified and naturally promulgating across the firm. As a top performing analyst, I had countless formal and informal interactions with the rest of the investment team explaining my investment process (Science), approach to allocating resources (Legwork), and how Zen practices improved my decision making (Art). The better performers were retained and promoted, while the poor performers exited. All this happened without top-down decisions. It was a self-organising system that sooner or later thrived in whatever market it entered, scaled relatively easily, and endured in an industry where firms rarely survive beyond a single generation of managers.

This contrasted with my experience at the boutique manager I worked at prior to moving to Fidelity. Here, there were no individual performance metrics, the variable bonus was small relative to the base salary and at the full discretion of the CEO, resources were centrally controlled, and the firm promoted a particular investment process. Nonetheless, it was a successful boutique, primarily due to the skills of the key investment manager. Without a shift in the organisational structure, it would struggle to scale and endure beyond that single successful manager’s tenure.

Amazon re-engineered

Let’s now turn back to Amazon, where Bezos and his management team set about transforming his company into a self-organising system. Around 2002, the entire organisation was broken down into what he termed two pizza teams, groups fewer than ten people. These units would create their own service objectives (motivation), act autonomously (freedom), and be resourced up to get the job done (energy). Each objective needed a performance indicator and the personal approval of Bezos. The teams were free to compete with each other and sometimes duplicate their efforts (at Fidelity we sometimes had the same stock covered by multiple analysts), with their offering available both internally and externally. The level of resourcing was dialled up and down depending on the likelihood of success. Bezos had broken Amazon down to its most basic building blocks and empowered these teams to drive decisions.

The idea had mixed success; some units required more than ten people, while others didn’t have easily quantifiable performance indicators. Additionally, asking people to create their own performance targets creates a conflict of interest. What it did do was move the organisation toward distributed decision-making, with higher levels of accountability and the option to offer any or all of the generated value to external parties. Each team could now move quickly, experiment, iterate. The organisation as a whole could scale quickly and in different directions, without being encumbered by top-down decision makers. Resources could be allocated organically, efficiently, and by those best-positioned to assess the risks and opportunities.

A natural result of the unusual attributes of an organism that could simultaneously be large and nimble, was that it started to dominate the areas of the value chain where scale was most important, such as where network effects are present (e.g. the marketplace and delivery network); large capital is required (e.g. logistics and warehousing); and the cost of producing an additional unit is low (e.g. digital products). Through its dominant position, it was then able to extract value from other parts of the chain through increasingly favourable terms for itself.

Let me draw an analogy here. My parents owned a florist in a large shopping mall for over ten years. The mall enjoyed network effects (bringing buyers and sellers together) as well as protection by local zoning laws. Having established a strong (perhaps the strongest) position in the value chain of selling flowers, the mall could extract any value my parents created through higher rents. This really hit home one year where it demanded a 26 percent rent increase. As I sat across from the Centre Manager negotiating, I realised there was really nothing we could do – the business fully depended on the foot traffic the mall delivered; we simply had to wear it. Today, as consumers migrate online, the economic rents charged by the malls are unwinding, while those available to Amazon are rising.

Bezos takes it to the next level

Amazon’s technology infrastructure was in need of an overhaul. Following Grand’s approach, Bezos put together a team to identify the most basic building blocks of computing. The first blocks on the list included storage, bandwidth, messaging, payments and processing. Each of these would have a dedicated team and be offered as a service both internally and to third parties. Bezos issued the following edict:

All teams will expose their data & functionality through service interfaces.

The only communication allowed is via these interfaces.

All interfaces must be designed to be exposed to outside developers.

Anyone who doesn’t do this will be fired.

Not only did this flip the internal decision making from top-down (IT team) to bottom up (autonomous service teams), but it also set the stage for a completely new paradigm of computing. Bezos proclaimed that “developers are the alchemists and our job is to do whatever we can to get them to do their alchemy.” Amazon Web Services set off with the mission “to enable developers and companies to use Web services to build sophisticated and scalable applications.”

Executing on this strategy was far from easy. Amazon’s developers now had to treat other developers as potential security threats; any programs written had to work with other programs; issues might bounce through twenty service calls before the owner was identified; and so on. Bezos was living up to his words: “We are working to build something important, something that matters, something that we can all tell our grandchildren about. Such things aren’t meant to be easy.”

From an economic perspective, the large capital costs of data centres and the fixed cost of software development could now be spread across both Amazon’s business and third parties. Just as with the e-commerce marketplace and the warehouses, Amazon was naturally ending up in the part of the computing value chain where scale is most important; modularising and subsuming any excess value from the rest of the chain. Our estimated value of AWS is over one third of the total business.

How this relates to investing

In the last few notes, I sketched out Kasa’s investment process, broken into its three basic elements:

Art: the decision maker making better decisions

Science: a decision making framework

Legwork: the gathering and analysis of information

Kasa’s decision making framework (Science) adopts the viewpoint of investing in businesses, rather than trading stocks. From this perspective, we are most interested in free cash: the cash that is left over once all other financial obligations have been met. The worth of the company is the present value of the free cash it generates over its life.

Our job is to assess the likelihood of the free cash the company needs to generate in order for the shareholders to achieve a ten percent return, given the current market price. There are two broad factors that determine a company’s financial performance:

Business: the industry structure & market position

People: countless actions by the staff, management and directors

So, in order to assess the likelihood of our achieving the ten percent return, we primarily focus on these two aspects. Amazon’s organisational structure has a substantial influence on the millions of decisions its employees make each and every day. Understanding Amazon’s organisational structure has increased my confidence in both the gradient and durability of its free cash flow profile. Looking at the implied numbers, I remain confident it will deliver our ten percent target return.

Amazon is a superior organism within the corporate jungle, but to what end? In a future note, I’ll shed some light on Amazon’s north star.

Sincerely,

Alipasha Razzaghipour

Investment Manager

Note 1) Please don’t take what I have written about Fidelity as an endorsement of its investment products. First, the incentive structure was designed to maximise shareholder profits, with client returns a means to that end. In other words, there is a natural force to transfer any economic value resulting from superior organisational structure back to the company’s shareholders. Second, during my decade there, I watched the unfortunate erosion of this self-organising system – I can only imagine those who designed it are long gone, and the new people either don’t recognise what they have inherited, or are not empowered or incentivised to sustain it. For the sake of my friends who are still there, I do hope things have started moving in the right direction. Either way, all organisms are impermanent.

Note 2) Most, if not all, of the ideas in this article are from other people, notably: Jeff Bezos, Steve Grand, Brad Stone, and Steve Yegge.

Never miss an update

Stay up to date with my content by hitting the 'follow' button below and you'll be notified every time I post a wire. Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia's leading investors.

4 topics

After an extensive career across RBA, Ausbil & Fidelity, Ali founded Kasa Investment Partners to solve the agency problems within the investment industry and derive a more direct relationship between the portfolio manager and the investor.

Expertise

After an extensive career across RBA, Ausbil & Fidelity, Ali founded Kasa Investment Partners to solve the agency problems within the investment industry and derive a more direct relationship between the portfolio manager and the investor.