The Australian superannuation performance test: Sensible but flawed?

In July 2021 several changes were implemented as to how superannuation (super) funds were run in Australia, under the banner of the “Your Future, Your Super” (YFYS) reforms[1]. The intention was to make it easier for Australians to follow what was happening with their retirement savings and compare the performance of their super scheme. One of the most significant changes was the introduction of an annual performance check. I think it’s worth taking a closer look at how this performance test works and some of the issues it raises because New Zealand has been known to follow in Australia’s footsteps when it comes to retirement savings, which could lead to the introduction of a similar test here at some point in the future.

The YFYS performance test is now done every August and compares the net return of every super fund for the past 8 years to a performance benchmark based on its Strategic Asset Allocation. If you fail the test you are required to notify all your members of the failure and develop a plan to address the underperformance. If you fail it two years in a row you must close your superfund to new members and, if appropriate, work out a plan to close the superfund and exit the industry. A somewhat nuclear outcome for the manager of the super fund. Hence the diagram below.

A diagram that shows priorities in a Performance Test world.

Source: The Conexus Institute

Clearly this new YFYS performance test became a massive concern for investment managers who were underperforming their benchmark over an extended period of time. And this appears entirely appropriate. Investment managers that, after fees, deliver a return less than the benchmark are not doing the job they are being paid for. As in any walk of life, charging for a service you are not delivering should not be sustainable.

However as with any new legislation there can be some unintended consequences. A handful of superfunds knew they were likely going to fail the first test, in 2021, and possibly even the second test, in 2022, given how far behind their benchmark they were. This creates a situation where those managers need to have significant out performance in the near future or face the consequences of failing the performance test. A response to this could be to take on more risk but if that is a deviation from their investment philosophy and process it may not have the intended outcome.

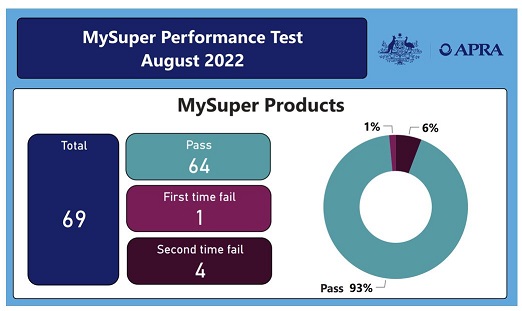

The results of the second annual YFYS performance test in August 2022

Source: APRA

So here we have the super funds that ended up failing the performance test and remember the funds that have failed for a second time in a row can no longer take any new members. It is a very public naming and shaming, that could ultimately lead to being forced to shut up shop. I have done zero research into these super funds and have no insight into the drivers of their underperformance.

However, I would note that an 8-year performance test would have almost certainly led you to considering firing Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger in early 2000. Berkshire Hathaway was a significant underperformer at that time due to their dislike of the heavily in favour Telecom, Media and Technology sectors. Munger and Buffett stuck to their guns and were vindicated when that part of the market collapsed in the early 2000s. But would they have behaved differently if they had been faced with an 8-year performance test, that if they failed, could threaten the future of their business.

A chart showing the underperformance of Berkshire Hathaway from mid-1998 to early 2000

Source: Bloomberg

Obviously, we will never know the answer to that but it’s a line of questioning that led to a very interesting paper by The Conexus Institute titled “Assessing the impact of YFYS through interviews with CIOs of funds with performance 'buffer'”[2]. The idea here was to interview the managers that had good performance and were ahead of their respective benchmarks and had a good sized “buffer”, to assess what impact if any the performance test had on how they invested.

Several of the CIO’s admitted that they were reviewing their allocations to some assets which did generate long-term return but were more volatile, such as Emerging Market and Small Cap equities. This is to be expected as investment managers know that a performance “buffer” has been created by taking active risk, but continuing to take active risk creates the risk (arguably the certainty) of a future period of underperformance. That scenario would erode their “buffer” creating the risk of failing the performance test in the future. The conundrum here is that taking less active risk reduces the chances of future out performance.

The Conexus Institute paper also describes “limp mode”. This is where a super fund has a small “buffer” and cannot take the risk of further underperformance, least they start failing the YFYS performance test. In “limp mode” it is very difficult for a manager to focus on generating superior long-term returns, they are much more likely to become quite short term focused. One of the CIO’s interviewed summed up that situation perfectly, “That scenario of small buffer: it’s like turning up to a gladiator event with a butter knife!”. The Conexus Institute believes that a sizeable proportion of the industry is in or close to being in “limp mode” which does not appear to be a great foundation for an industry that should be looking to create great long-term returns for their clients.

It should be noted that all the CIO’s interviewed for the paper agreed that there should be some sort of performance test to protect consumers. However, the majority believed that the current 8-year performance test was significantly flawed. Most felt that the introduction of a qualitative aspect to the test would improve overall outcomes for consumers. Interestingly the Australian government announced that upon review they will be making changes to the YFYS performance test, most significantly moving to a 10-year test and would look to make further improvements to the test in the future[3].

5 topics