The biggest risk to dividends right now

If, in the first three months of the year, financial markets were digesting the enormous liquidity poured into the system, at another level they were also wrestling with the growing possibility that strong economic growth will trigger inflation. I’ve discussed this previously, but at Talaria we feel it is worth revisiting because there is probably no bigger risk for investors. In fact the 12-month expectations in the US show particular strength with the headline CPI estimated to move from its current 1.7% rate to 3.5% by May and core moving to 2.3%.

The investor resistance

There is understandable scepticism for many on whether this will happen. Since the early eighties, there has been an inexorable decline in developed market government bond yields as deflation (falling prices of goods and services) has been the order of the day. Japan for thirty years and other central banks since the GFC have consistently failed to reverse this trend.

Whether or not governments, now adding their considerable weight to the efforts of monetary authorities, can engender inflation is yet to be seen. However, the balance of probability has shifted more towards rising prices.

The investment implications of inflation risk

If investors were positioned for inflation, then this shift wouldn’t be a problem. However, the evidence is that many are placed for the status quo: for there to be a lid on prices and for interest rates to stay low.

Most investors’ intuition would be that the less their money is earning in the bank or in so-called risk-free assets such as bonds, the longer they would be willing to have that money tied up elsewhere. If interest rates are zero, then a share offering a dividend yield of 1% might look attractive.

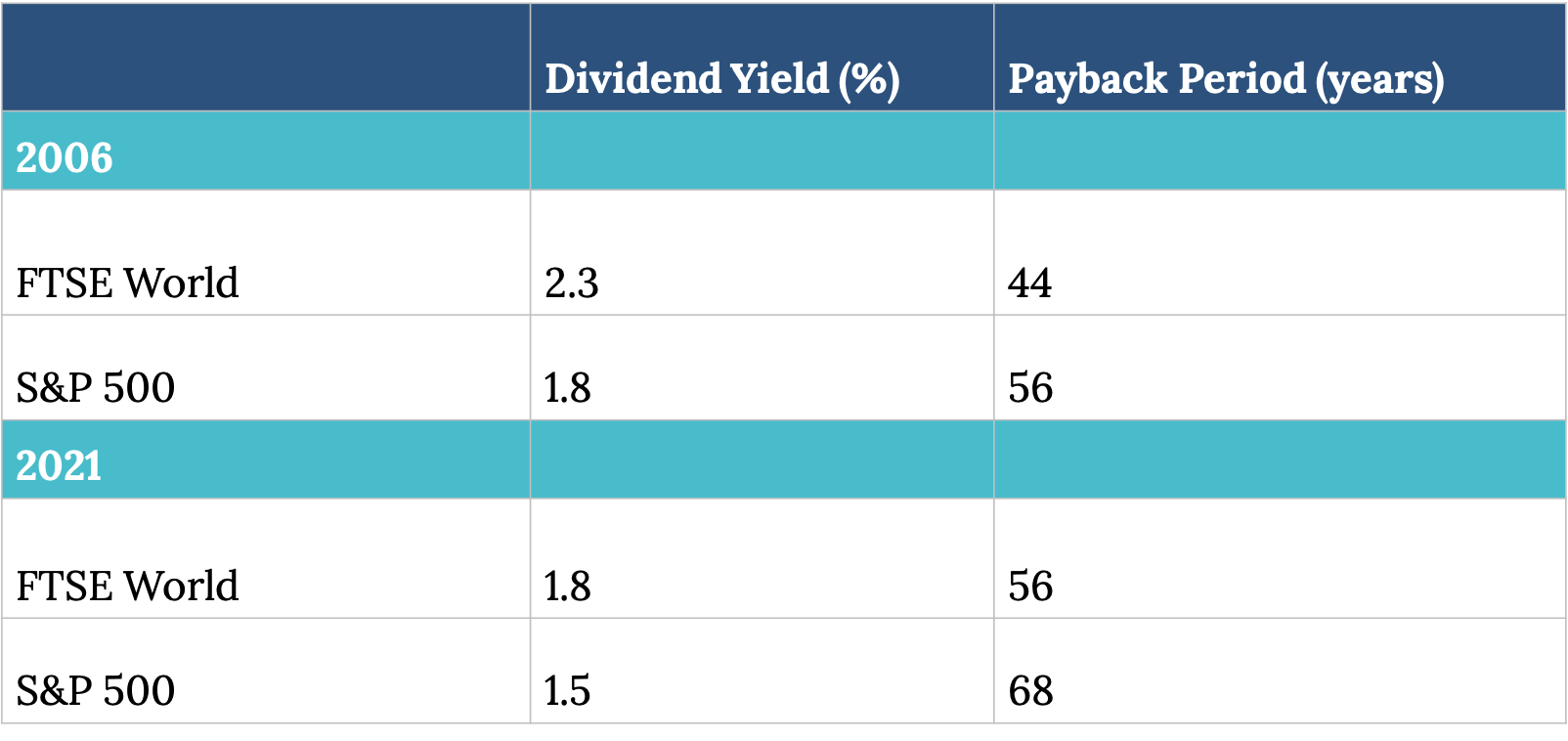

Looking at the last fifteen years, this intuition has been one driver of the falling dividend yields offered to global investors: FTSE World index, and the S&P 500 (table below):

Dividend Yields and Payback Periods

Another way of expressing this falling dividend yield is a measure of the time it takes to recoup an investment.

Looking at the table above and all else being equal, in 2006 a buyer of the FTSE World index at a dividend yield of 2.3% would expect to recoup her money in just under 44 years. In 2021 someone buying at a dividend yield of 1.8%, would expect to recoup her money in just under 56 years.

Falling dividend yields and longer payback periods become a problem when interest rates rise. In these circumstances, the opportunity cost of being out of an interest-bearing asset increases.

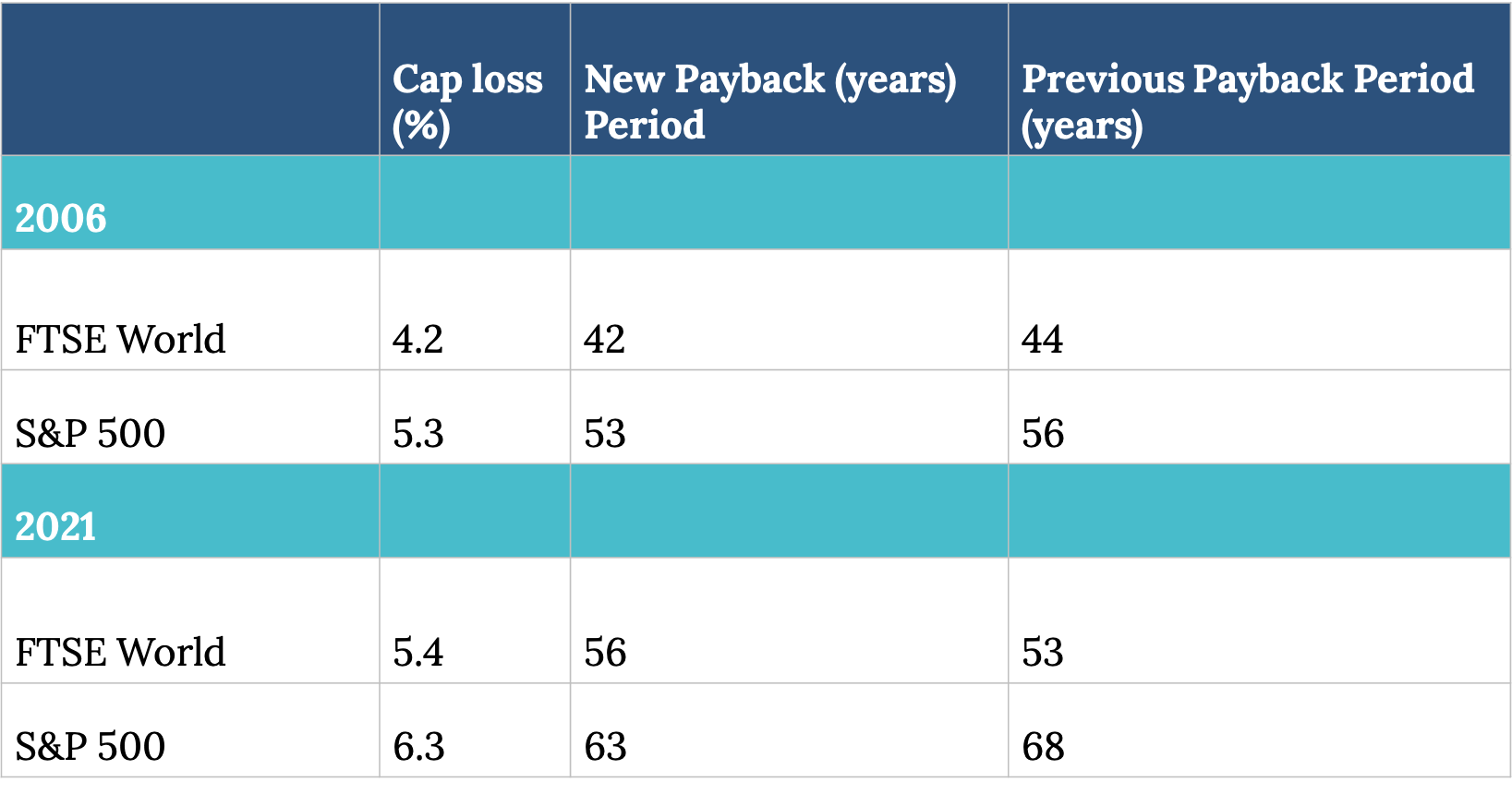

As this is the case, an investor should want a higher dividend yield to compensate. The table below shows the implied reduction in the value of capital if investors require an increase in dividend yield of just one tenth of one percent (10 basis points).

Capital loss and payback periods assuming investors require a 10-basis point higher yield

So focusing on the S&P 500 over the last 15 years, its payback period increased about 20% from 56 to 68 years. The same scale of change in yields would require a repricing of equity to compensate. Thus, a 10bsp increase in yields, all else being equal, would leave equity holders with losses of some 6.3%, while a 0.50% increase – a return to the rough average of the last 20 years which took in the internet bubble and housing bubbles – would leave the US market 26% lower and payback of circa 50 years.

Usually, the act of making a change rather than maintaining the status quo feels the riskiest thing to do, in this case, it’s just the opposite.

Not already a Livewire member?

Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

4 topics