The bottom - are we there yet??

Time in the market beats timing the market.

Price is what you pay and value is what you get.

The biggest risk is not taking one.

Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.

More money is lost waiting for the crash than in the actual crash.

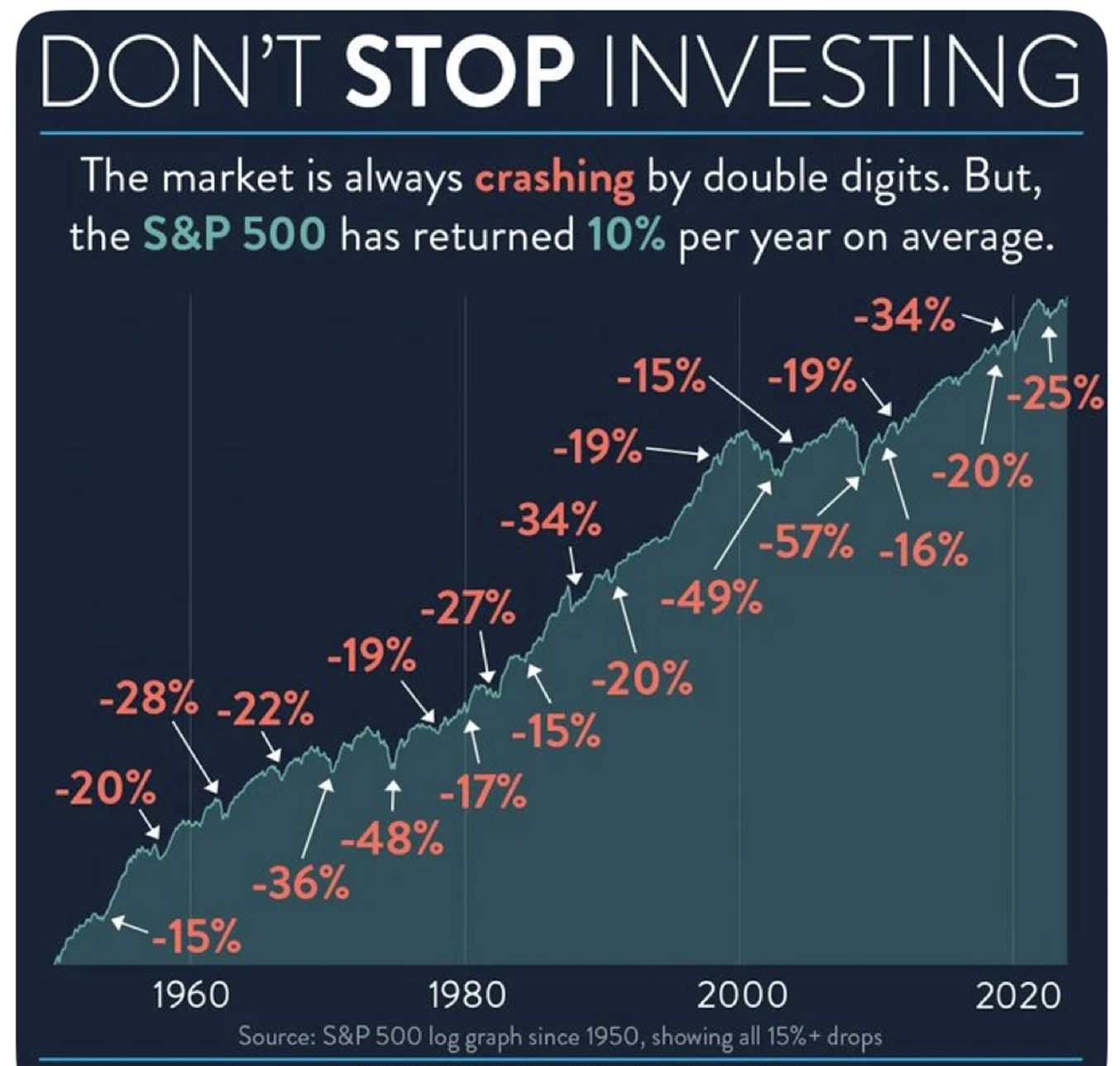

These are all sayings that are true, that are well known, that have stood the test of time, and that also apply to today’s market.

So why are so few investors acting on them? Because the most uncomfortable thing to do in investing is to try to “catch a falling knife”, and especially in a falling market that is sentiment driven, and that can change on a dime because of one tweet. Imagine getting out, then Donald Trump tweets something, and markets rally 6%, 8%, 10%, and you are out of the market.

It is hard enough to buy in these moments without thoughtless social media posts, but it is especially hard now. That means lots of people don’t buy, and even worse, many people sell. But if you’re a long-term investor, is this the right thing to do?

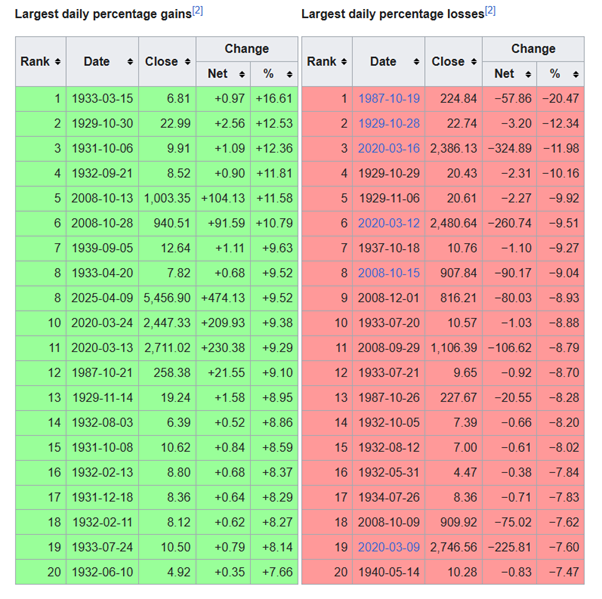

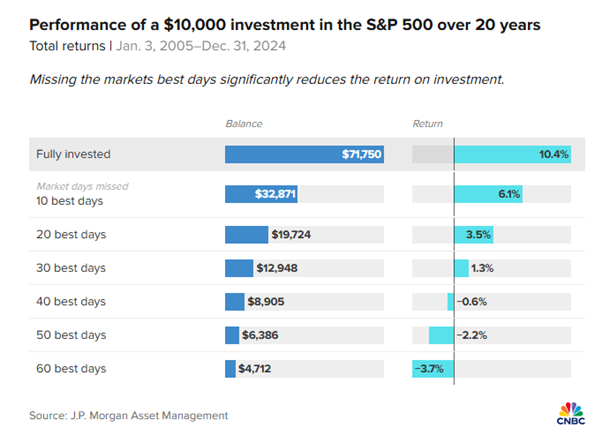

We all know the stats about hammering your return by missing the best 10 days, but what you might not know is how often the best days and the worst days are right next to each other. This idea that you can somehow discern exactly when to get in and when to get out is nothing short of pure bunkum.

To be fair to current day would-be investors, it’s all well-and-good to assert that over the long-term you’ll be fine, the truth is that the long term is made up of a series of short terms, and getting those short terms right (or as right as you can) should also be one of the goals of deploying investment capital. In fact, only by making it through that series of short terms do you end up becoming a long-term investor.

To aid that end, let’s go through an exercise to make you feel better about investing now, or if you’ve recently got some capital to work.

To be very clear – this is NOT personal advice. If you want or need personal advice, please consult a financial professional. This is an illustrative example of long-term investing, and no more. Whilst some may argue this example is potentially accurate, past results are not indications of future returns.

I think I can quite precisely pin-point the 2 worst months in modern investing history to get money to work – they are March 2000 when the S&P 500 hit 1553, and October 2007 when the S&P 500 hit 1565 (interestingly, you’ll find that the month of October pops up a lot when you’re talking about bad investing months).

Go with me here – let’s say you sold half your company in January 2000 and the close date was going to be 1 March 2000. Your company is worth $20 million in post-tax proceeds, so you get $10 million after you sell half. You still have half your company, and it delivers you enough income to pay your bills and then some, so you decide to go all-in on stocks and you buy the S&P 500. After all, it’s the deepest and most liquid equity market on the planet in the home of global capital markets.

What could possibly go wrong??

Well, ignoring the nuance of the exact numbers, you sit back, and you watch the S&P 500 fall to 769 in October of 2002, and your $10 million turns into $5 million. Between the tech wreck and the 9-11 terrorist attacks in the US, markets crumbled (I’m only focusing on the S&P 500 for the purposes of this piece, and whilst it was bad, very bad, the Nasdaq was even worse – much worse. It was down 86% intraday-peak-to-intraday-trough through this period).

But you’re a long-term investor who has earned a lot of income from their business, both pre-sale and even after you’d sold half of it. So when you do the deal to sell the other half of your company in June of 2007, for $10 million to you post-tax again, you decide – I’ve saved some money, I have some passive income, so I don’t need this new liquidity right away. Now that the S&P 500 is back to where I got invested in 2000, surely it just goes up from here. I mean, the value of my home has skyrocketed lately!!

So in you go in October 2007 – all of it, back into the S&P 500. And over the next year-and-a-half, you watch the S&P 500 fall to 667, and the value of your now $20 million falls 57% to just over $8.5 million.

There are a variety of reactions that are possible from here, and I don’t need to spell them out. But let’s say that you had done a good job of saving money up to now, and you have some passive income, and you do some consulting on the side so the truth is, you don’t need the money you invested in the market (and that you lost more than half of). You leave it, you almost forget about it. You leave the corpus as-is but you do decide to distribute, and to spend, the income this dwindling portfolio kicks off.

And you leave it until March 2025 when you’re considering giving your kids some money and you’ve heard that Trumpy’s making the markets go bump in the night. And looky here - your measly little $8.5 million from 2009 has grown to…..wait for it……

$31.8 million. That’s not a typo – it’s now almost thirty-two million dollars.

The first lot of $10 million has an annual compound growth rate of 5.45%, and the second lot of $10 million has an annual compound growth rate of 7.82% (by definition, that “second lot” includes the “first lot” that went sideways for 7-and-a-half years). And remember, you took the income over that whole time and in the S&P 500, that added around 1.5% per year, making the two annual returns around 7% and over 9%, respectively.

Read that again – this hypothetical person has invested at arguably the two worst moments in modern investment history and still, they end up with somewhat solid long-term investment returns.

That’s why people talk about being a long-term investor. And the whole way along, you could have got money out if you wanted to (you had minimal liquidity risk), you had options on where to invest if you’d wanted them (likely a globally diversified portfolio), and you had full transparency into what you were in and how it was going (all public and even some private markets have good transparency).

And as it turns out, even though it didn’t feel like it at the time, it was going just fine.

Get good advice, build a plan, ignore the noise, execute well.

Now let’s go back and look at the sayings I posted at the top.

Time in the market beats timing the market.

Price is what you pay and value is what you get.

The biggest risk is not taking one.

Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.

More money is lost waiting for the crash than in the actual crash.

Good luck out there.

5 topics