The budget blows hard

Had the Australian population agreed with the mainstream press that the FY21 edition of the Commonwealth Budget was the “most anticipated” in years, then they would have been greatly disappointed as the night unfolded. The pre-budget leaks were extensive, and the forecast deficit ($200 billion) was well in line with market whispers. The Treasurer’s budget speech provided the “gap filler” of expenditure initiatives to show how Treasury got to their forecast.

As the speech unfolded, it became increasingly clear that during the COVID recession, it is the Treasury and the RBA together that are running the economic policy response. The Government, the Opposition and the Parliament may have some thoughts, but they are largely bystanders to the big economic policies that are being undertaken.

These policies can be simply summarised: Spend Big (Treasury), Print Money (RBA) and Hope for the Best (Politicians).

A range of commentators suggested that the budget forecasts are highly dependent on several short term premises. For instance, they point to the budget’s assumption that a vaccine is available in late 2021, or that household/consumer confidence returns from the fast tracking of tax cuts, or that internal borders re-open, or that iron ore prices hold up. It is our view that these short term factors will be completely outweighed (over the longer term) by two significantly more important premises: (1) that both the Treasury and the RBA are surely hoping that interest rates do not materially rise over the next ten years, and (2) that Australia’s bond issues will remain well sought after by international creditors.

Those are the two crucial premises upon which the budget outlook rests for the next three years and beyond. Any sustained rise in inflation or any major correction in bond yields across the world would spell danger. The counter balance to these risks is the RBA’s QE program. It is our view that the RBA will be unrelenting in its use of QE to ensure that the Government’s interest costs do not blow out, even as debt grows to $1 trillion. Thus, if there is a hint of a bond market correction then the RBA, like all major central banks, will use QE as a weapon to hold yields or interest costs down. This is a sober outlook that all investors, particularly self-funded retirees, need to understand.

What will unfold in Australia will be a re-run of what we have seen first in Japan, then in Europe and the USA. However, Australia has a fair chance that we will manage to wriggle out of the low growth and deflationary cycle that is consuming our Western peers, based on our stronger population growth (once borders re-open to immigration) and firm commodity export markets. Until then, we must push through with extraordinary fiscal largesse funded through increasing debt managed via supportive QE programs.

The budget forecasts

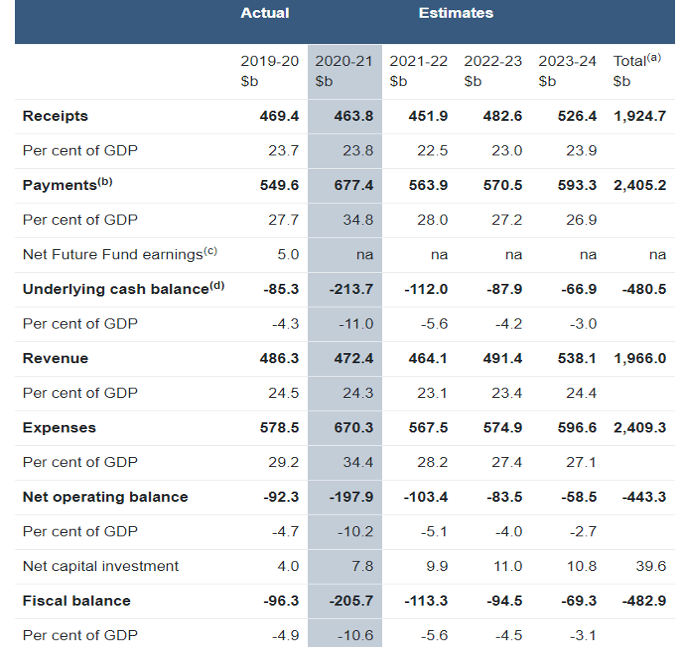

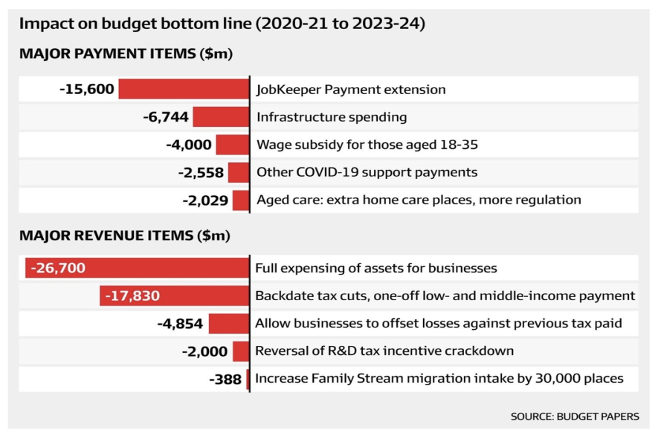

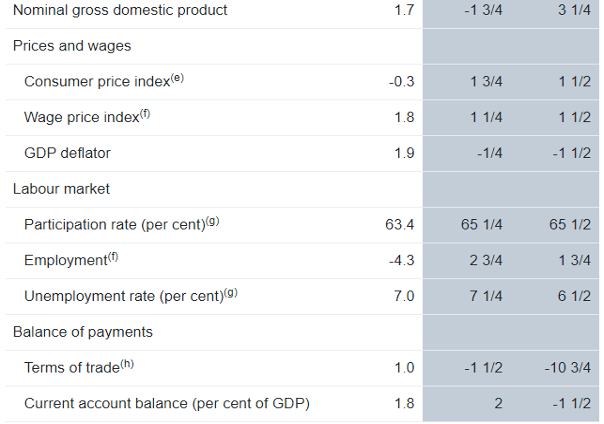

Our first table outlines the expenditure and revenue forecasts of Treasury, some of which we regard with scepticism given the current uncertainty regarding border re-openings both internally and externally.

Looking first at receipts, we can see that these are forecast to hold steady in dollar terms in FY21 from FY20, but moderately rise as a percentage of GDP (23.8%). In FY22 receipts decline substantially on both measures. Whilst timing in tax collections may give some explanation, the forecast declines in FY22 are consistent with the dramatic economic downturn in GDP that are we are enduring. It is arguable that Treasury is too optimistic for receipts in FY21, although they have reported that taxation collections are exceeding their projections in the first 2 months of FY21.

On the payments side, we observe more feasible forecasts. Government COVID support outlays surge from 27.7% of GDP to a staggering 34.8% and take the fiscal deficit to 11% of GDP.

Treasury forecasts that quarterly GDP will recover to FY19 quarterly run rates by the September quarter of FY21. Whilst this forecast (captured in the next table) is supported by surging Government expenditure, it seems optimistic given that international borders (in the main) will probably remain closed and unemployment will still be in the range of 7.25%.

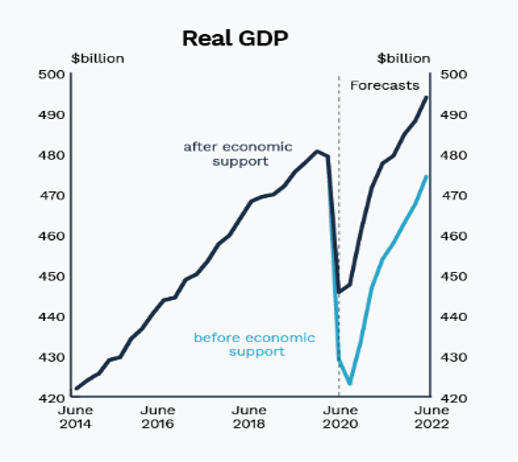

The above graph shows that Australia’s GDP was at an annualised run rate of $1.92 billion in the March quarter of FY20 (pre-COVID). Treasury forecasts that the quarterly run rate will be regained in just 5 quarters. Without the fiscal stimulation (11% deficit), the recovery would have occurred later in FY23. In bald terms, the Government will spend $2 to recover $0.20 of growth. Net Commonwealth debt will double over 4 years as the economy grows by about 5% from FY20 to FY24.

The next table shows the individual components that drive the GDP recovery.

Predictably, the GDP declines of FY20 and FY21 are expected to be followed by a sharp bounce back in FY22. The forecast components of the recovery include a surging recovery in business investment (non-mining) that is expected to flow from the “instant write off” announced in the budget. However, this will drive up imports of capital goods and offset mild export growth. An expected decline in the terms of trade and bulk commodity prices will push the trade account into the negative, and the current account will slide into deficit as foreign borrowings surge. Australia will slip back into a period of deficits and will need to tap international debt markets. One implication if this eventuates: the AUD will again come under pressure.

The above table also outlines the sobering outlook with wage growth that barely matches inflation. The projected recovery in dwelling investment is muted given the significant declines recorded in FY20 and FY21. More first home buyer assistance is needed, particularly as demand from immigration drops. This leads to the forecasted slow recovery in jobs, with unemployment still at recession levels in 2 years’ time.

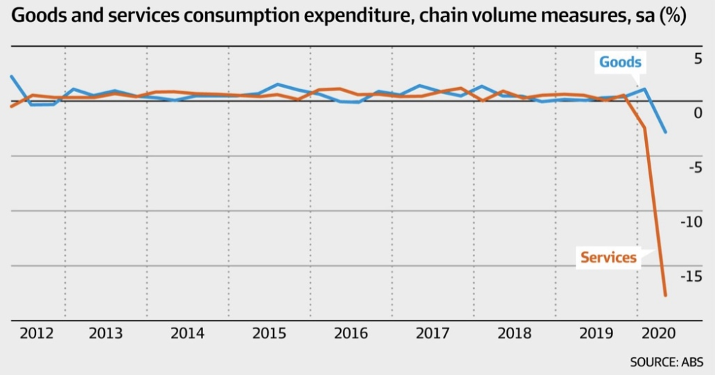

Throughout the budget speech, there was a conspicuous silence regarding the outlook for a key aspect of the Australian economy. Australia has a significant and deep services sector that filled the gap created by the demise of manufacturing some 20 to 30 years ago.

Australia’s employment, business and thus economic recovery is very much dependent upon recovery in the services sector – chiefly tourism, hospitality, education and entertainment.

The next chart shows the significant decline in services consumption since the March quarter. An expected recovery in goods expenditure/consumption driven by “sugar hit” tax incentives will not make up for the damage to our services sector. A recovery in services employment is highly dependent on domestic and international borders being fully re-opened.

Australia’s economic decline and debt blowout

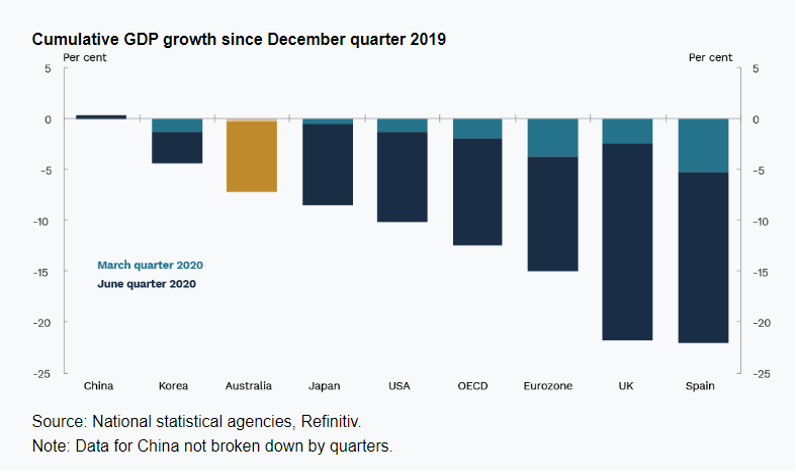

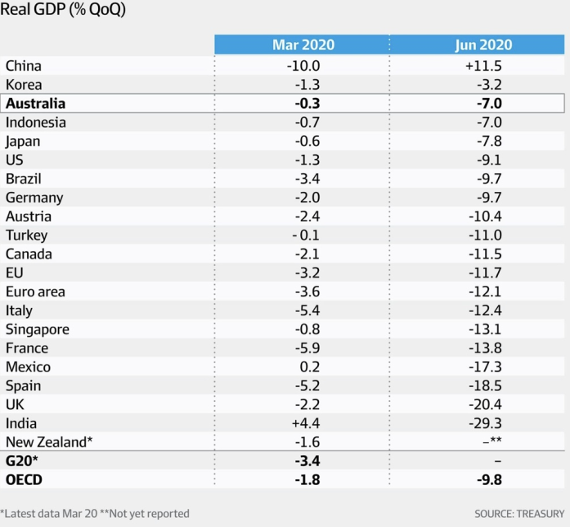

The budget papers presented a graph outlining the economic declines felt across the world’s major economies. The following graph shows that Australia has faired well by comparison, largely explained by the size and speed of the fiscal response, the closure of our international borders, and the (mostly) effective management of the pandemic. The Treasurer highlighted this in his speech.

Of real significance is the marginally positive growth recorded in China - our largest trading partner. Their economic recovery is remarkable and shows their unfair advantage in generating sustained economic growth. Their economic journey that includes transforming their workforce from subsistence farming to manufacturing and creating a consuming middle-class, still has decades to run, albeit at decelerating pace. Whilst international trade has been important for China in the early part of their journey, its relevance will be less as local consumption grows. Of course, Australia’s bulk commodity and energy exports are beneficiaries of this cycle, but we urgently need to diversify our economic trading partnerships. Unfortunately, at present, the alternatives have poor economic growth outlooks.

The table highlights the sharp economic declines felt across the world in the June quarter. For instance, the latest economic reports suggest that in the June quarter India declined at an annual rate of -29%, the United Kingdom by -20%, Spain by -18%, France by -13%, Germany by -10%, the US by -9% and Japan by -8%.

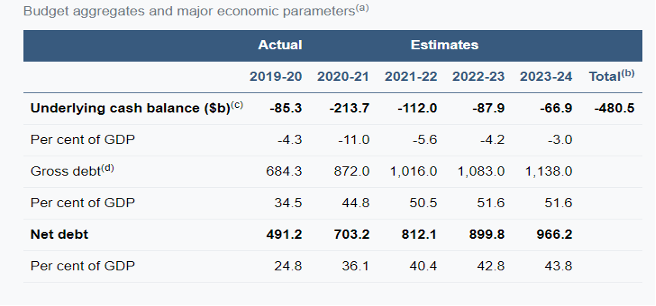

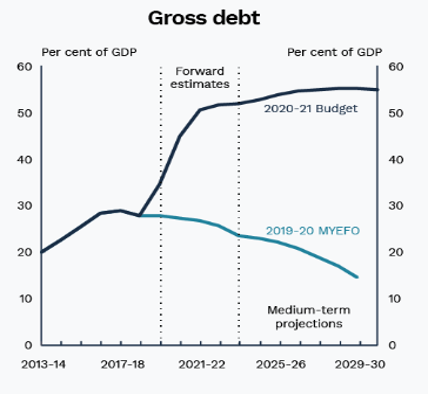

The budget papers outlined the projected growth in Commonwealth debt that will emerge from years of fiscal deficits. It is currently forecast that it may take until FY25 for the fiscal deficit as a percentage of GDP to fall below the growth in GDP. At that point, Commonwealth debt to GDP will stabilise.

In broad numbers, by the time gross debt reaches $1 trillion, the Australian GDP will approximate $2 trillion, giving a 50% debt to GDP ratio.

Further, based on the tax base (receipts) of 24% of GDP, it will be imperative for the RBA to maintain the cost of Commonwealth debt (bonds) at below 1% across the yield curve. Using a target rate of 1% average cost in FY25 suggests that 0.5% of GDP will be consumed by interest payments in the budget. Therefore, it will become increasingly difficult to balance the budget as the debt grows -even with negligible interest rates.

However, the compression of the yield curve and the “rolling over” of historic issued debt (bonds) will take a decade to pass. The table below shows the Australian Commonwealth bonds on issue, with their initial issue yields (coupon) compared to market rates.

The above chart shows recent issuance of bonds with very low coupons absorbed by the open market (but with support of the RBA’s QE program). As bond issues increase and old issues are rolled over, the need for QE will grow. This is clear given the worldwide surge in bond issuance by all major countries.

This outlook conjures up reflections on the Japanese debt and deflationary economic cycle of the last twenty years. It also makes us reflect on the last decade in Europe as relentless QE has been undertaken by the European Central Bank following various financial crises across southern Europe. The COVID crisis has unleashed another unlimited QE program. In the US, their national debt continues to grow, and it now exceeds US$26 trillion or 110% of US GDP. It seems likely that most of the western or developed world economies have entered a type of Japanese economic cycle of low growth and bouts of deflation.

The world is awash with Government debt, with interest rates held near zero and below the inflation rate. The well intentioned and documented plans set around the turn of the century for the formation of economic policies to meet the demographic challenges of an ageing developed world population have turned to dust. The western world has now seemingly succumbed to a continuous cycle of bail-outs to fund persistent fiscal imbalances. The policies created evolve around currency printing or so-called “Modern Monetary Theory” and no one knows if it will work. Only time will tell.

Australia has now joined our peers in these policy settings. However, we retain the ability to reset our economic policy and therefore our economic outlook once international borders are re-opened. Our massive superannuation system ($3 trillion in size), and our ability to turn on the immigration tap after a few years of infrastructure rebuild, places us in an enviable position compared to the rest of the world.

In the meantime, both the Treasury and the RBA will be working hard to secure our economy by making the budget blow hard to puff some air into it. Whether they are making the right decisions matters little because they are implicitly forced into these programs by the policies of our peers. What really matters is the hope that inflation does not reappear and blow up the value of bonds and push governments with high debt loads into financial crises.

Not already a Livewire member?

Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors. Enjoy this wire? Hit the 'like' button to let us know.

2 topics