The Buffett-y approach to value

A degree in aeronautical engineering is surely the most unconventional route for a career in funds management but it's a route that has greatly assisted Nick Kirrage, portfolio manager of the Schroder Global Recovery Fund. Being a value-focused investor, Kirrage believes that the one thing his degree taught him is not to guess, but rather to look at financial history and make informed decisions.

In this wire, Kirrage unpacks value investing in the current environment. He discusses why value investing has been frowned upon, and why it's paid off to be a contrarian investor. We chatted at length about the rotation we experienced last year from growth into value and whether that is actually sustainable.

We also discuss why predicting what markets will do is a futile exercise, but rather looking at patterns of human behaviour is a lot more constructive. Kirrage reflects on his career as a contrarian investor and even gives a few tips to those starting their investment journey.

From soaring in the skies to funds management

Kirrage grew up obsessed with planes, and not the fancy space planes as he describes them but those that take people on holiday. So, when it was time to pick an area of study, he naturally gravitated towards aeronautical engineering.

But that dream was short-lived. He recalls getting a subsidy from the UK Government while he was at university, which (in his words not mine) "was money for people to drink beer."

"The government gives you this big grant cheque which is free money to spend on normally rent and so forth and everyone just spends it on beer. But I was only spending half of it on beer and I spent the other half of it investing in the stock market."

His passion was then ignited. Kirrage continued his degree but got an internship at Schroders one summer. He caught the investing bug and he's been at Schroders ever since.

But looking back, Kirrage is grateful for his unconventional path into the finance world.

"Everyone I worked with studied economics or business studies. The thing I took from engineering is don't guess. A lot of people in investing like to rename guessing to make it sound more sophisticated and call it forecasting, but it is essentially guessing."

Rather, he suggests investors look to fact and history as an indicator of what could happen to markets.

"Try and base as much as what you do on fact, empiricism, on history, on things you think might repeat...That led me to become a value investor, which is all about history repeating in one form or another."

Why predicting what markets will do is futile in the short term

Beginning his career in engineering ingrained the concept of looking at concrete factors when trying to decipher markets, as opposed to relying on forecasts. Having a comprehensive understanding of the past epitomises this.

In a pandemic-riddled world that is driving economic circumstances and market events frequently described as "unprecedented", Kirrage urges caution.

"There is this desire to always believe we are unique and special and that this is unprecedented, and there is always some justification for that. You get very framed by what you've lived through, and it is important to look over longer periods to broaden your perspective. In doing so, you see much more extreme times: Second World War, oil shocks, inflation, Great Depression...There are a lot of proxies and what is going on now has elements of all of these.

Having explored history, what can actually be done with the insights? Well, Kirrage highlights that humans are creatures of habit and our approaches to markets are no different.

The most important pillar of value investing is inexorable mean reversion. There is one thing in stock markets that never changes: Us, the human element. We are not radically more rational than we were 100 years ago. We get very excited and bullish, and we get very negative and despondent when things go wrong. Much of value investing is built around exploiting that.

Humans hate losing, so when nervousness arises things tend to fall fast and further than they should. Taking a contrarian view to investing can capitalise on these opportunities.

One of the key things about investing is being consistent, and not getting caught in the tides.

The danger with being a contrarian is that the market is not always incorrect. There are periods where it can be consistently right, or if not where it can outlast you. It is no use buying a cheap name if the recovery is seven years off. This is where the danger of Value traps arises.

"The market can remain irrational longer than you stay solvent" - John Maynard Keynes

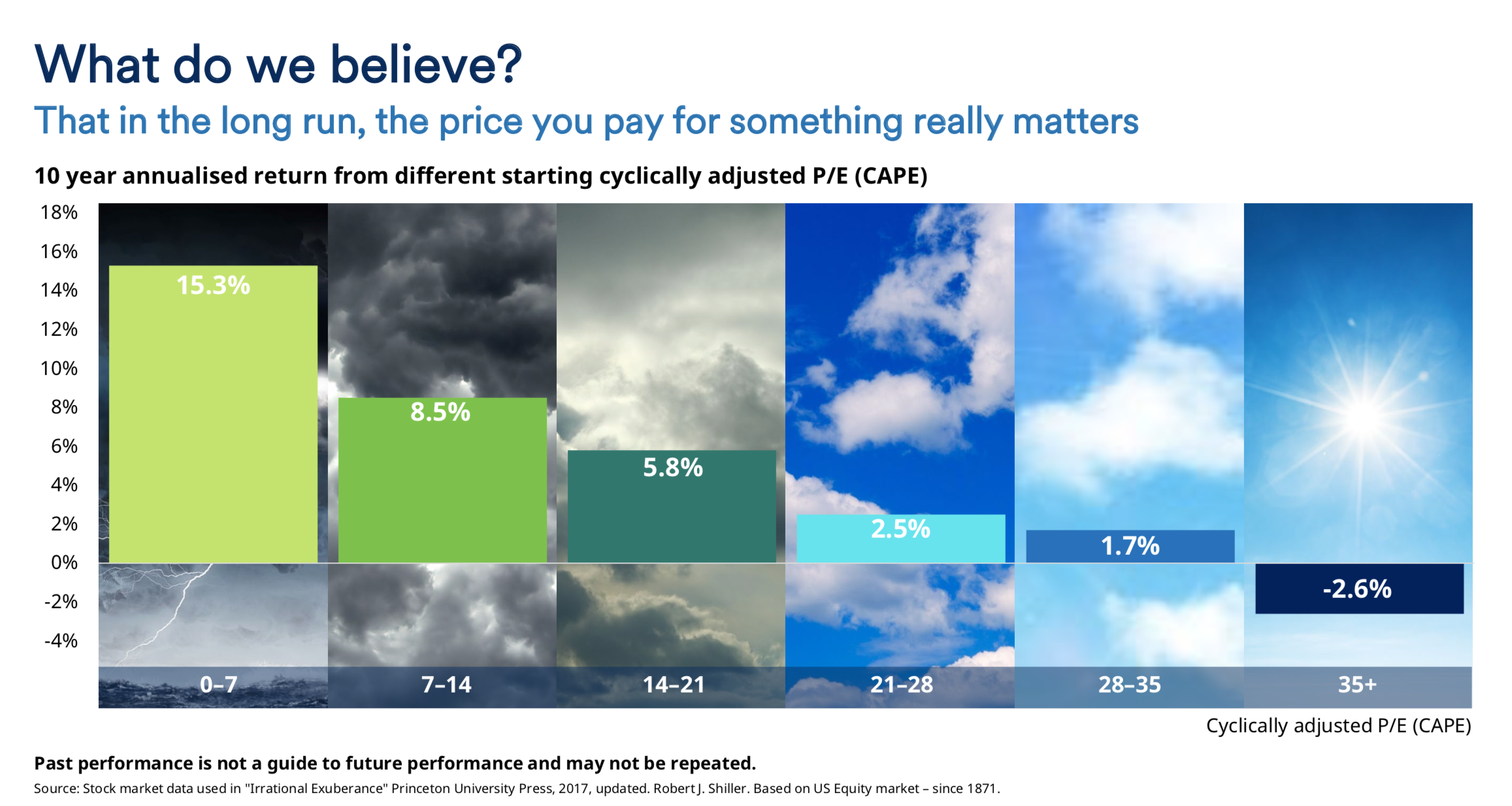

In reality, the stock market becomes easier to predict over long time horizons:

If you ask me where the stock market is going to be tomorrow, I wouldn't have a clue. But if you asked where the stock market is going to be in 50 years, I bet you my house it has gone up around 7% per annum.

Accordingly, Kirrage views the team's superpower as the ability to be patient and hold for new opportunities over time.

What actually is value investing?

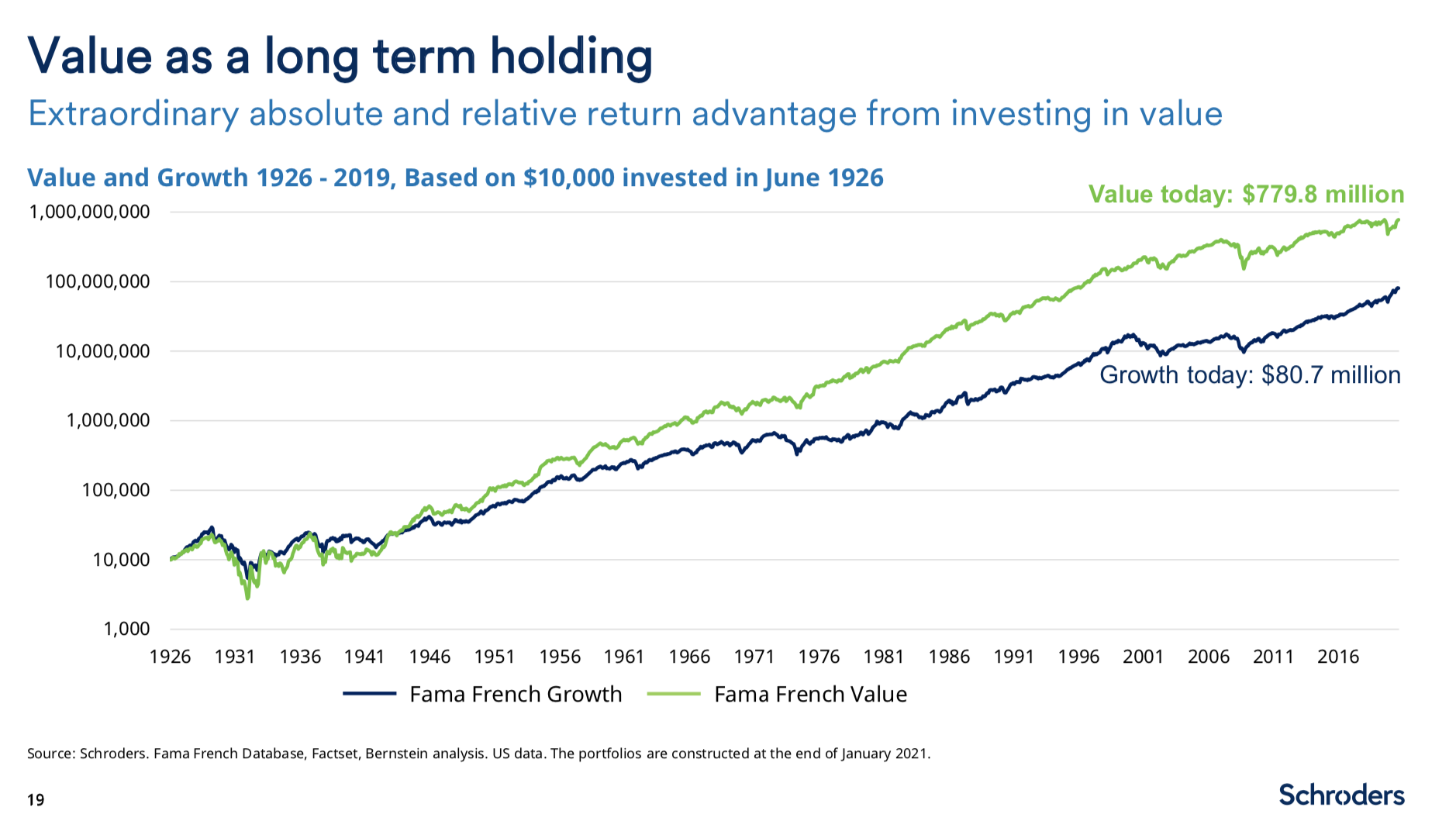

There is no defined church for value investing. The traditional perspective of buying a stock that you think will be worth more in the future is by definition just pure investing.

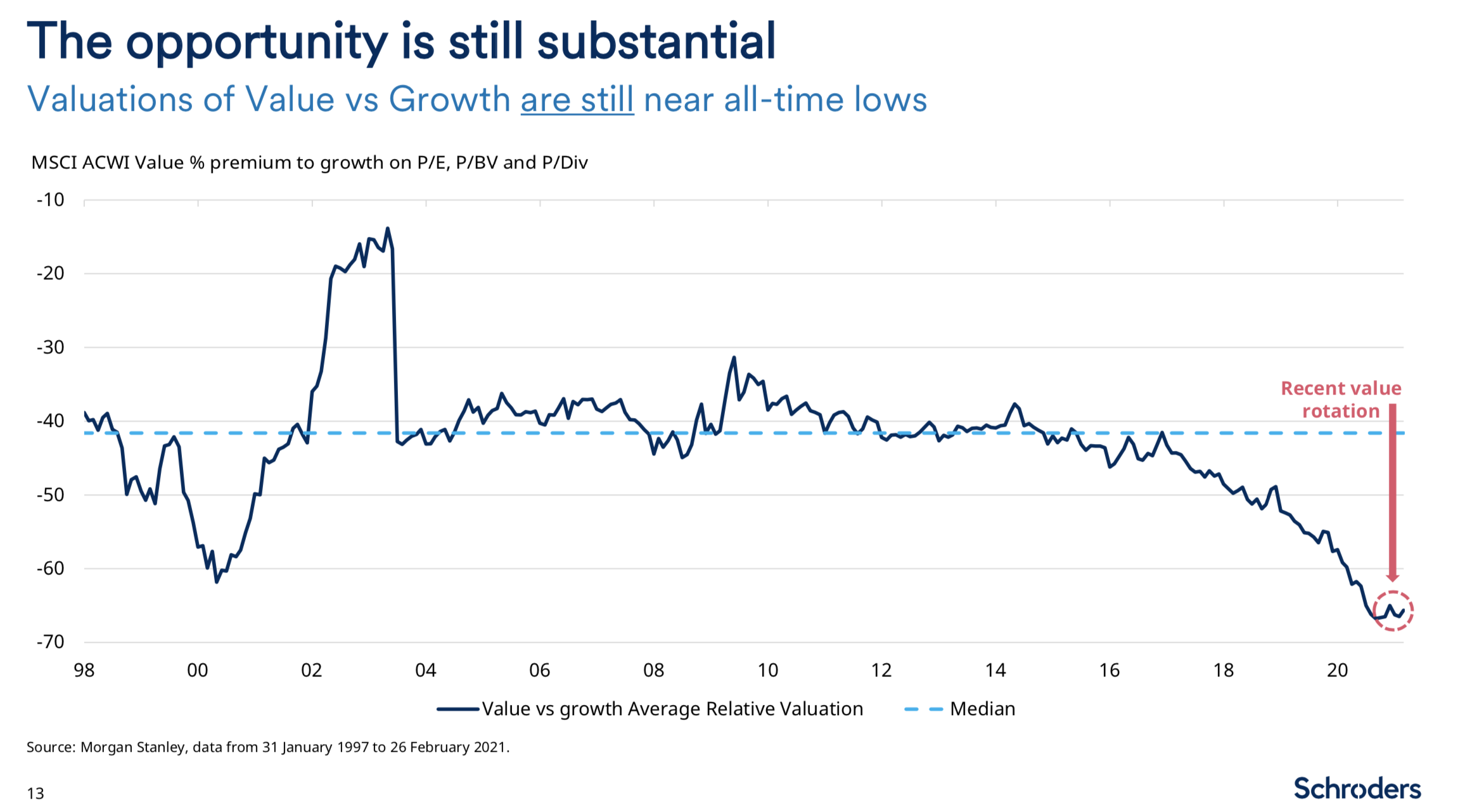

The Schroder Global Recovery Fund remains a very traditional value fund with its holdings, compared to a lot of traditional value managers that are embracing growth as a core given that is where the money has been. Kirrage thinks that over the long term, the fact value has been so out of favour over the past 10 years present a great opportunity.

To characterise value investing

The Buffett-y approach to value is where you are focused on buying the best businesses at a reasonable price, and watching them compound forever. On the other end of the spectrum, we analyse the cheapest 20% of the market and isolate the dogs from the diamonds.

Valuation is just a result of human behaviour. Value investors use these metrics (PE, multiples) as a scientific process to decide where the opportunities lie.

If you were to buy this bottom 20% of valuations over the past 120 years, you would have outperformed the market. That isn't a bad place to start, and I'd bet on myself to be able to work out which ones are the complete disasters.

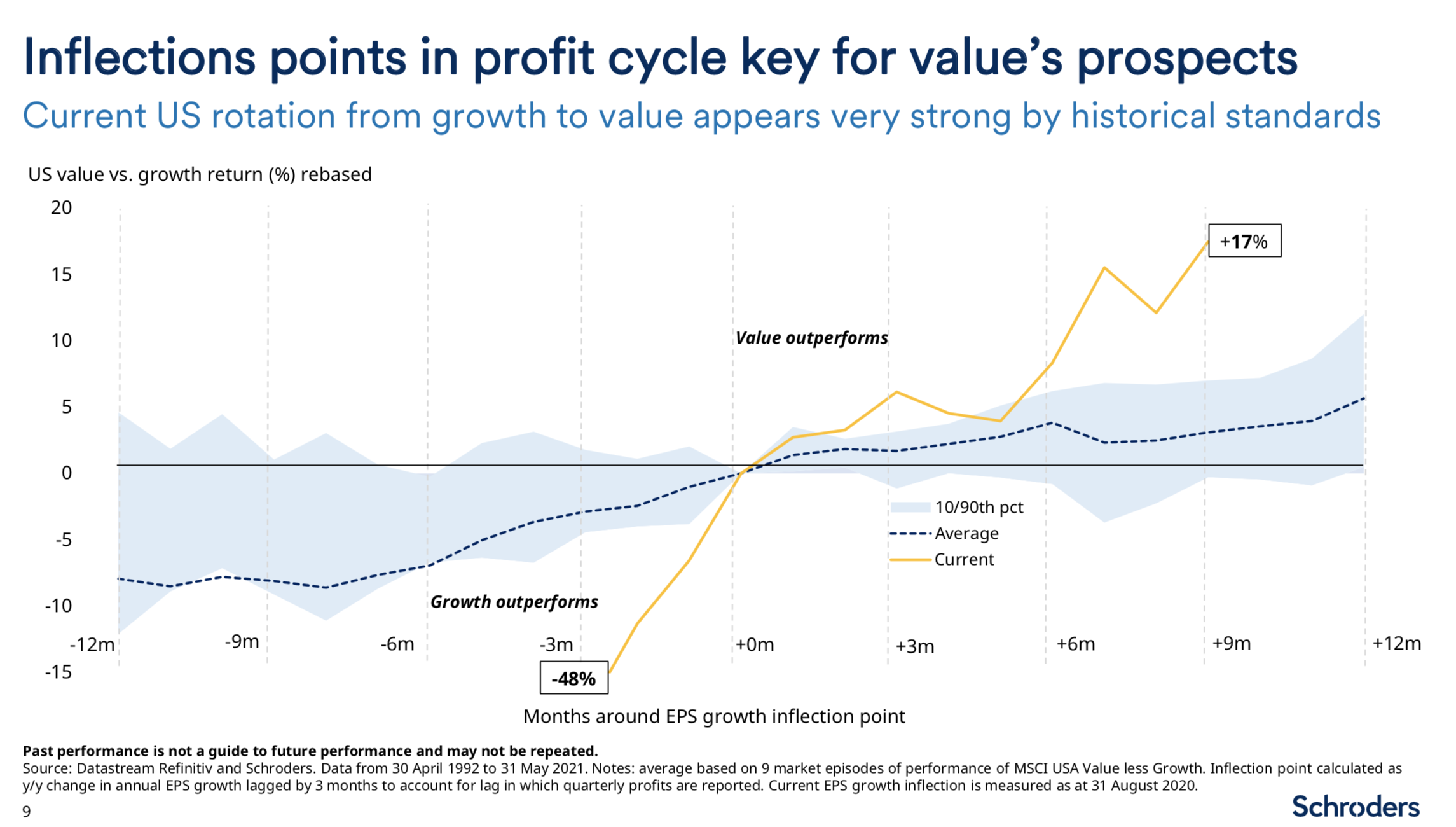

The great rotation

Over the last six to eight months, we have seen a big rotation from growth obsession into value stocks and cyclicals. Kirrage views the fixation on this as a narrative humans use to explain phenomena, but these don't necessarily need a label.

"There is a human desire to create a narrative for everything that happens. Stock markets are an out-of-control freight train, but we need this narrative to help explain what is going on."

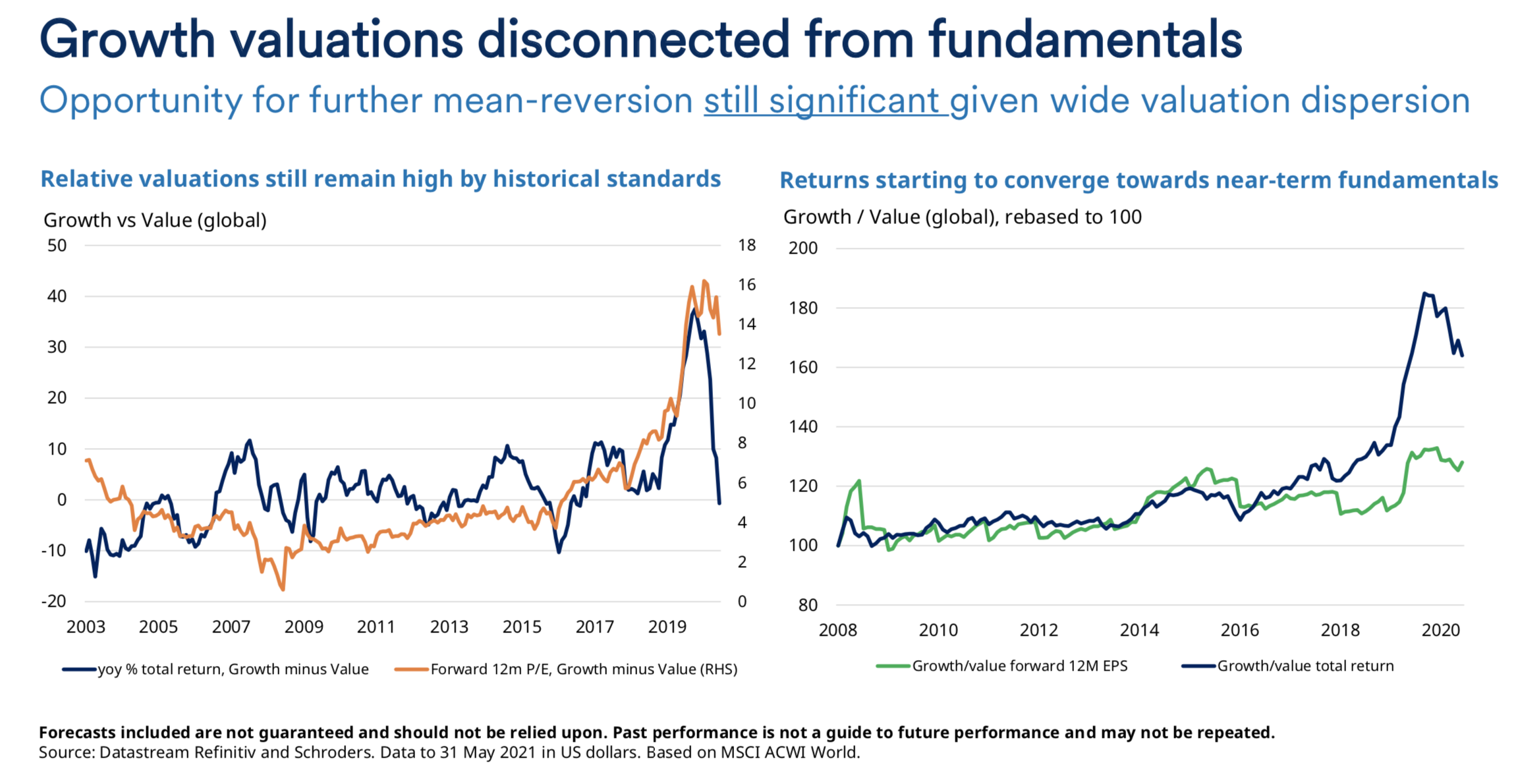

Furthermore, the recent divergence between growth and value has been much more extreme than historical levels. Potential drivers include quantitative easing and government stimulus.

"Is this pumping up valuations and supporting debt-riddled companies that would struggle in standard economic conditions? Maybe, that seems reasonable. But to claim that was the sole reason would be overly simplistic."

Markets are as bullish as ever, M&A are coming back and buybacks are rampant. In Kirrage's view, this all looks like a manifestation of human emotion: People are extremely positive, perhaps overly buoyant.

"A colleague of mine used to say, the bigger the party, the worse the hangover."

Value looks compelling, so you have to be careful where you tread. We have suffered the biggest GDP fall since the Second World War, and now we have valuations at the highest levels in history. Does this make sense?

"History suggests the best way to protect money is to not overpay for investments. It turns out that is also the best way to make money."

As for what may drive this eventual convergence between returns and fundamentals:

"If I knew that, I'd go to Vegas. If we look back to the big market reversals in March 2003 and April 2009, it is extremely hard to find a catalyst. One day, there is just more buyers than sellers, and eventually the human momentum follows."

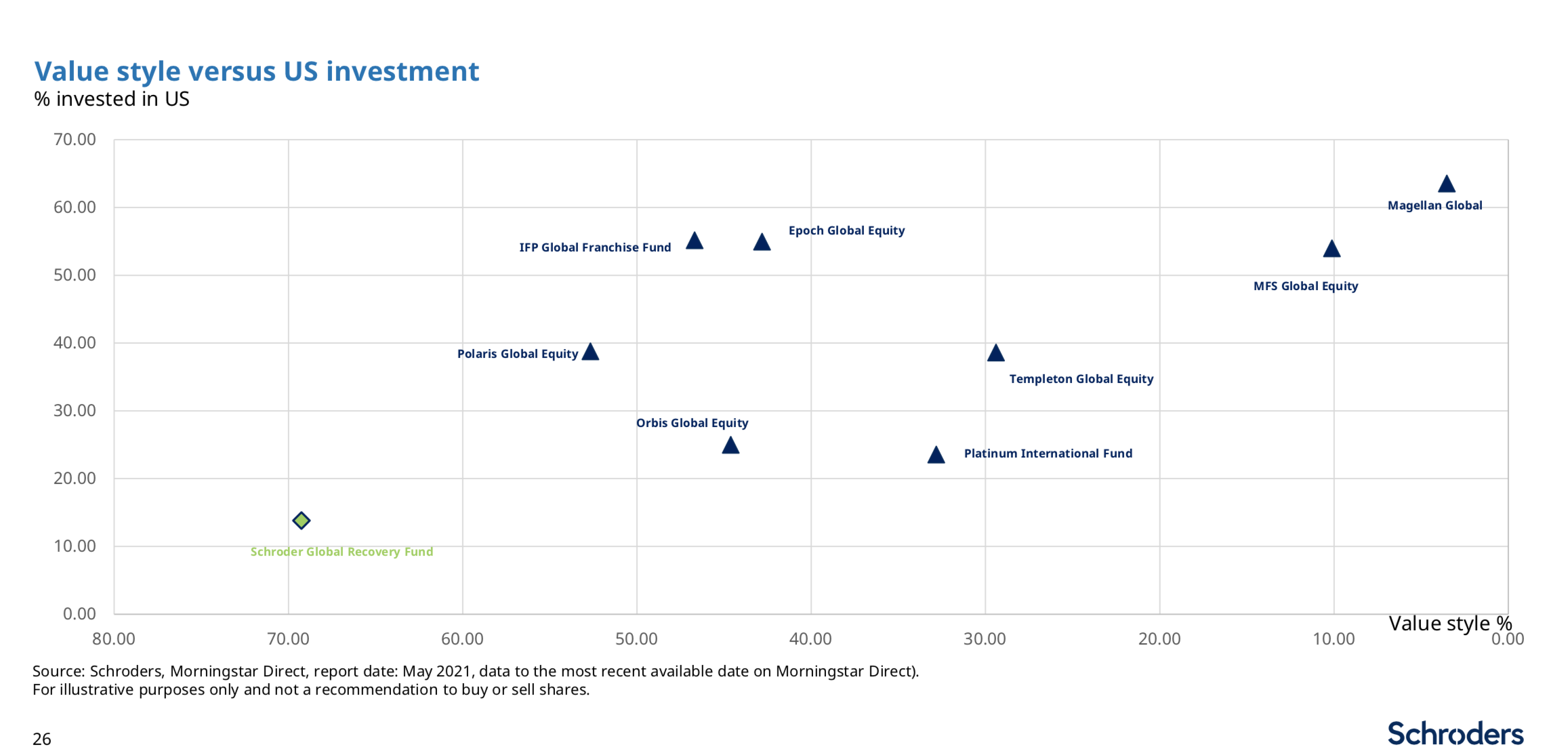

Getting stuck into the portfolio

Moving into the specifics of the Schroder Global Recovery Fund portfolio, what pops out is their extremely overweight allocation to Europe and underweight US. Being aware of home ground bias is incredibly important when constructing the portfolio, but that is not the driver here.

"Our portfolio reflects what we see from a valuation perspective. The US is 60-65% of the global benchmark, and they are on a CAPE* of 39. The peak CAPE in the tech bubble was 45. Above 38, the US has never made a positive return across the subsequent 10 years."

As for the opportunities in Europe?

"Europe is incredibly cheap, and is 5% of the global benchmark versus 25-30% of the fund."

There are many reasons for this, with some of the most compelling being:

- BREXIT. All the negative press and political coverage scared markets

- The UK's economy is filled with old companies that no one really wants, such as banks and mining businesses

- Currency has had a lasting effect too, with a strong US dollar and weak Sterling.

"The UK has rarely been this cheap relative to the rest of the world over the last 50 years. There are also examples in the rest of Europe and Japan. The mix within our portfolio reflects where we think opportunities lie, as opposed to any sort of bias or looking at competitors."

Looking at emerging markets, predominantly China, they have been one of the worst performers for value because the valuations quickly became excessive. Yes, there have been compelling catalysts and trends as they decoupled from the Western world. Why haven't they done well then?

"Investors were paying too much. It's not enough to understand the macro themes perfectly. You need to pay the right price."

The team applies a global screen across all investment opportunities and remain index agnostic when deploying capital.

*CAPE: Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings

Lessons along the way

A five-year timeframe allows the fund to give companies every chance to succeed. But there are inevitably times where an investment thesis will shift, particularly in a period of frothy markets. This is where it becomes important not to catch the proverbial knife. A particular case study where they bought then had to prematurely sell for a loss (and a company that ended up going bust) was Diamond Offshore, an oil drilling rig business.

"Ultimately, with the world shedding oil assets Diamond was posed with a binary outcome: either their rigs get rented at very profitable levels, or they remain vacant and get nothing for the assets. It had predictable cyclicality going back 50 years, and after 4-5 years of underperformance leading to a crushed share price, as well as oligopolistic characteristics and sensible management, it posed a reasonable investment."

On balance of probabilities, this small position presented a small chance of losing a lot of money and a very reasonable chance of making some if not a lot of money.

The company retained indebtedness and were burning cash flow, and the cycle was not turning fast enough. At the end of the day, there was too much of a chance of them going bankrupt so the fund exited their position. But Kirrage highlights that this is all in the nature of their fund.

"We aren't in the business of buying something that can't go down: That's fixed income. We are here to find something that may make you money and being right more often than not. If we don't have any of these outliers, we just end up covering our backs and becoming the index."

Ultimately, investors need to learn from every investment they make and understand the process behind the decision.

"This is a game of averages. We just need to be more right than we are wrong. If you lose money, analyse why you lost the money. Because maybe 8 times out of 10 your choice would have been vindicated. The same applies when you make money. Maybe you just got lucky - is this repeatable? You need to figure this out and grind results for your clients over 30+ years."

When it comes to standout companies in business quality that remain on absurdly low valuations, Kirrage finds himself wondering if he is missing anything. But that is all part and parcel of the job.

"For example, we have owned Morrison's for 5 years and it went nowhere. Now it's up 50% in a month and has received bids from 3 companies.

It is all about finding a mean where you understand what is required for a company to make money from a completely objective stance.

"Our job is to not miss anything big. Often in value investing, you can understand why people don't want them: These reasons are all over the headlines. The question is whether these are short-term or long-term factors. If they're short-term, we can wait it out and ride the upside."

Overall, Kirrage reminds us that investing is centred around being more right than wrong. Does he think every position in the portfolio is a winner? Absolutely. Is this likely? Probably not. But with a process committed to grinding out returns for clients over the long term, you can be confident Nick will always be on the prowl for the next name set for a big recovery.

Access unloved stocks with long-term growth potential

Nick seeks to identify stocks which trade at a substantial discount to their fair or intrinsic value and where profits growth will surpass expectations. To be the first to read his latest insights, follow him here.

5 topics

1 contributor mentioned