The case for breaking up: 3 ASX demergers that went well, and 1 that should

When asking a parent of multiple children if they have a favourite child, they will typically say that they are all equal and they have no favourite. For me this is completely true, but for most others they are lying. The same could be said for companies.

Whenever we ask a CEO or chairman which of his/her divisions he/she is most excited about, they always answer that they are equally excited about all divisions. Again, I believe that this is a lie.

Every CEO/board has a favourite division. Capital is a scarce asset and, when push comes to shove, that capital will tend to gravitate to the favourite child. When there are extra corporate costs, they will tend to be shoved more to the less loved children, which has the impact of understating the earnings of the 'ugly duckling'.

The CEO and chairman are then often forced to make a choice about which division is their favourite child as they must make the decision about where they are going to remain.

In the slew of recent ASX demergers including:

- Woolworths (ASX:WOW)/Endeavour (ASX:EDV),

- Graincorp (ASX:GNC)/United Malt (ASX:UMG), and

- Iluka (ASX:ILU)/Deterra (ASX:DRR),

The CEO and chairman both decided to go with Woolworths, United Malt and Iluka respectively.

In the Tabcorp (ASX:TAH)/The Lottery Company (ASX:TLC) demerger, the chairman went with The Lottery Company despite having a self-professed great relationship with the racing industry.

What happens next?

The 'ugly duckling' company will typically get a new CEO, a new board and generally a new culture. We articulated in our first demerger note that some of the outperformance can be explained by the extra attention a demerged entity gets. However, we think it runs deeper.

The new team running the demerged business are unshackled from corporate overheads and frustrating constraints. This can give way to a new culture which is hungrier, leaner and more agile. This demerged business can make the right investments and seize on market opportunities without having to prepare a pitch book for head office.

The role of lifecycle in company demergers

Some companies are great companies with great culture forever and some companies are badly run companies and have poor cultures forever. Most companies are somewhere in the middle. They go through periods of good decision making and periods of poor decision making.

Generally speaking, poor decision making usually occurs at points in time when things are going well. Either the cycle is in the company’s favour, or the management team are basking in the glory of previously astute decision making.

The point here is that the worst decisions are generally made when times are good. We believe the opposite is also true. When people/companies have their backs against the wall, the survival instinct hones one’s decision-making ability, and people tend to make their best decisions. But, as we've mentioned, we have observed most companies drift between arrogance and humility.

Case study: ASX supermarkets

One example is the supermarket sector in Australia. While there are smaller competitors, it is essentially an oligopoly with two major players, Coles (ASX:COL) and Woolworths (ASX:WOW).

Over the last couple of decades, the ascendancy in terms of market share, profitability and share price has swung between Coles and Woolworths. What we have observed is that there is an almost seven-year cycle as one of these companies moves from the outhouse to the penthouse and vice versa.

For Woolworths, when things were supposedly at their best in the mid to late 2000s, they started to get arrogant. They focussed on rolling out new stores, maximising short term profitability through price increases and thought it was a good idea to start a new hardware business, Masters, from scratch.

This ended in a lot of pain for shareholders as the company stretched its balance sheet and got distracted away from its core business – selling groceries. At this point in time, they were well and truly in the outhouse. This is when we observed the board and new management start to make smart investment decisions.

These included shutting down Masters, taking the short-term profit hit by improving service and dropping prices, investing in the store network, investing in their supply chain, developing best of breed online offering and data analytics, and demerging Endeavour.

The point is that most listed companies go through periods of good and bad decision making. Our observation is that generally speaking, good decisions are made during periods of humility and bad decisions are made during periods of arrogance.

We believe that this could be one of the reasons that demergers tend to work. Demergers tend to occur in businesses when the company is going through that part of the lifecycle where they have worked out that they cannot be all things to all people.

I believe that this is another subtle reason why demergers tend to work. When a board and management are arrogant, they prioritise getting bigger over maximising shareholder value. Therefore, a demerger would not rank highly as an option as it would signal that they are not masters of the universe. In turn, the culture of a company leading to a demerger tends to be a little humbler, at which point there is generally better decision making.

Why markets prefer pure plays

This last reason is probably the most basic, but still a good reason why demergers tend to work. Markets generally tend to prefer pure-play companies over conglomerates.

We believe that market participants are pretty simple creatures. We believe the market is more likely to ascribe a higher value to a pure-play company than it would to a division within a conglomerate. This sounds asinine.

Surely market participants would be clever enough to assign the same valuation to the same business within a corporate structure as it would if it were to be stand-alone?

Sadly this is not the case.

When market participants want to get exposure to a theme, they will pay a material premium for that pure-play company rather than a division of a conglomerate in the sum of the parts.

Iluka v Lynas

Iluka has a market cap of $5.3 billion. It has a mineral sands business which will generate earnings of $700 million and we think is worth around $3.5 billion and it also owns a $500 million stake in Deterra. Therefore, one can imply a value of around $1.3 billion for its rare earths deposit and refinery.

By our calculations, the volume and earnings from Iluka’s rare earths business in a few years’ time will generate earnings, revenue, and volume from its rare earths business just over 50% of Lynas. (Lynas has a market cap of $9 billion.)

By these measures, the market should be valuing Iluka’s rare earths business of at least $4.5 billion as a stand-alone business rather than the $1.3 billion attributed to it by the share price.

We suspect one reason for this is the conglomerate discount.

We also believe that this conglomerate discount is applicable even when there is no “hot theme” involved, given how market participants like to think about their investment portfolio.

"Pigeonholing" your investments

Investors like to pigeonhole their investments. Some investments they want to put in the bucket of companies with steady and predictable earnings growth, which they can model out for many years. Other investments are a bit more speculative where there are very few earnings now, but the growth potential is massive.

Then, there are the deep cyclical companies. These companies struggle at the bottom of the cycle but can generate a remarkable amount of cash at the top of the cycle.

The attraction for investors in these sorts of businesses is if you get the cycle right and are countercyclical, you can make a lot of money. The three examples above are by no means exhaustive but are illustrative of how investors have a tendency to pigeonhole.

Is distinct a bad thing?

The problem comes when there are companies that have two material divisions with materially different investment traits.

Take the Graincorp pre-demerger as an example:

- The malt business (subsequently called United Malt) was perceived to be a low growth compounded.

- The rest of Graincorp would be put into the "deep cyclical" camp.

- The “low growth compounder” investors didn’t like the volatility associated with the cyclical part of the business and the deep cyclical investors didn’t like the boring United Malt business as it diluted the cyclical leverage. (Those who want more excitement would look to companies like Elders (ASX:ELD).

When you separate these different businesses, you get a completely different shareholder base for the two companies over time. Management can run capital management and make investments based on its specific earnings stream and shareholders' preference rather than a hybrid of the two.

This is another reason why we feel the right demergers can work. As value investors, we like finding companies like these hidden gems within larger conglomerate companies where the market is unwilling to ascribe a proper value. We believe that one way or another, this value will get realised over time to the benefit of our unitholders.

As a major shareholder in both Iluka and Graincorp pre-demerger, we pushed the respective boards for these demergers and we believe that we were instrumental in getting them done.

Other Potential Demergers: Incitec Pivot

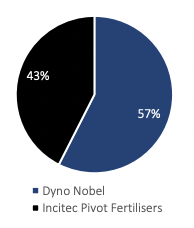

On 23rd May, Incitec Pivot (ASX:IPL) announced its intention to demerge its fertiliser business from its core explosives business, Dyno Nobel. This is something we have been pushing for and we believe that this is a smart move by the board. The corporate history of Incitec Pivot (ASX:IPL) is quite interesting. It started life inside Orica (ASX:ORI). Orica merged its fertiliser distribution business with a co-op called Pivot Limited, which was a fully integrated fertiliser company with the manufacturing of urea at Gibson Island. This merged entity debuted in 2003 with Orica maintaining a 70% stake.

In 2006, Orica sold out of Incitec Pivot. In the same year, Incitec Pivot bought Southern Cross Fertilisers from BHP. The main asset here was the DAP manufacturing facilities at Phosphate Hill in northwest Queensland.

Two years later, IPL bought Dyno Nobel which was a global explosives manufacturer. The interesting aspect here is that the 'child' became Orica’s largest competitor. In 2016, Incitec commissioned an ammonia plant in Louisiana.

As you can see, IPL has had an interesting corporate history with a conglomerate of different assets.

We believe that the fertiliser business is quite a different investment proposition to the Dyno Nobel business, an explosives business which supplies Ammonium Nitrate (AN) to mining and aggregates companies to blow up rocks.

This is a pretty steady business with long term contracts and a strong market position both in Australia and the US. In this example, you would call this a “low growth compounder”.

The other part of the business is the fully integrated fertiliser business. Its earnings are extremely volatile and leveraged to global fertiliser prices (specifically DAP and urea prices). It would be best described as a “deep cyclical” business.

We believe that the investors of each division are likely quite different and that, as it currently stands, the company is neither here nor there. Its earnings are too volatile to attract the “low growth compounder” mob and its fertiliser business is too small a part of the valuation to attract investors interested in that part of the business. This explains why we believe that the management and board would be in favour of a demerger.

We note they tried to sell the fertiliser business a few years ago, but to their credit decided to hold onto the fertiliser business when bids were not high enough. There is a lot going on in the world of agriculture and fertiliser at the moment.

Ukraine changed everything

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, food and energy prices (which were already on an upward trajectory) went vertical. Given Ukraine is the world’s food bowl and Russia was the largest exporter of fertiliser, the impact of the war and the ensuing sanctions will have a long-lasting impact on the agricultural supply chain.

Fertiliser is very energy-intensive and hence is also leveraged to skyrocketing energy prices. The point here is that fertiliser stocks in the US have rallied strongly over the last year, with Mosaic, CF Industries and Nutrien up anywhere from 100-140%.

Incitec over the same period is only up 44%.

We are sympathetic to the view that there could be a “stronger for longer” cycle for fertilisers.

With 20% of the world’s traded fertiliser likely to be sanctioned for the foreseeable future, underinvestment in fertiliser plants in the western world due to ESG concerns, high agriculture prices and the difficulty in increasing capacity, we think that existing fertiliser manufacturing companies have a decent outlook for the medium term.

We think the cash flow generation of the fertiliser division will be very strong in the short to medium term as we have difficulty seeing the supply-side response in the fertiliser market and farmers can only hold off application for so long. We think the time is perfect for IPL to demerge its fertiliser business.

In the event of a demerger, we suspect the CEO and chairman will stick with the explosives business as it is the “favourite child” and that the “ugly duckling” fertiliser business will get a new management team, new board, new culture a strong balance sheet, great cash flow and a new lease of life.

We think as a stand-alone entity it will be a cyclical but unique business with several growth opportunities.

Conclusion

As active value managers, we like investing in companies where there are hidden assets not being properly valued by the market. If we believe that there is material value accretion by demerging the undervalued division on a long term basis, we will push the board to consider such a demerger.

With this in mind, we feel strongly that Incitec Pivot should look to demerge its fertiliser business. We think that it dilutes the strong outlook for its explosives business through its volatile earnings stream. As a demerged entity, the fertiliser business would be able to get more attention.

10 stocks mentioned

1 fund mentioned