The Chinese iron ore cost of production

This is a short wire to accompany a longer article I wrote in my newsletter. I won't belabor the thought process, but simply set the scene, and explain my conclusion.

The problem of grade in mining

Ore grade is 11 parts of everything in mining.

Okay, so that is an exaggeration, but it is most of everything.

You do have to worry about metallurgy, and recoveries, and jurisdiction. However, if the grade is good, then you are most of the way there to a profitable project.

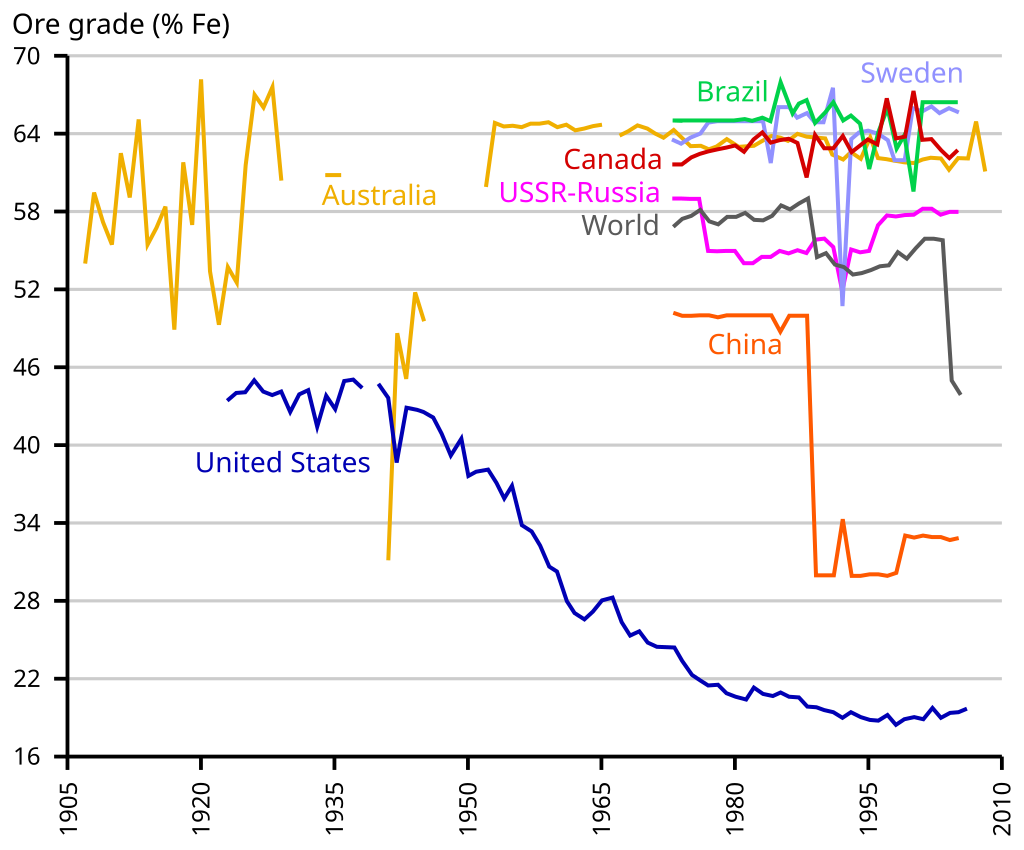

The chart below shows estimated grades for iron ore on a resource basis.

The big three seaborne iron ore trade producers, Australia (62% Fe), Brazil (66% Fe) and India (66% Fe), all have fantastic grades compared to most iron ore provinces on Earth. Simandou in Guinea, Africa, will soon join them with grades north of 65% Fe content.

However, look at poor China, with grades hovering around 30% Fe.

In truth, the picture is worse than that.

A much-neglected data anomaly

I have (literally) spent decades trawling through statistical data releases in financial markets. This experience makes me alert to any statistical anomaly that does not make sense and equips me with the tools to disentangle what is going on.

For example, see Where do the separated rare earths produced by Lynas actually go? in which I showed that they (mostly) go to China, and almost none to the USA.

Figuring this out was personally valuable.

I simply took my money out of Australian rare earths stocks.

There was absolutely no point because everyone had decided to "not sell to China" which had the natural consequence that they had no market.

A business with no market will fail.

Let us apply similar sleuthing to the China data to determine just how important seaborne iron ore is to that market.

It is more than I thought, and I will show you why.

How can a big deal become a small deal?

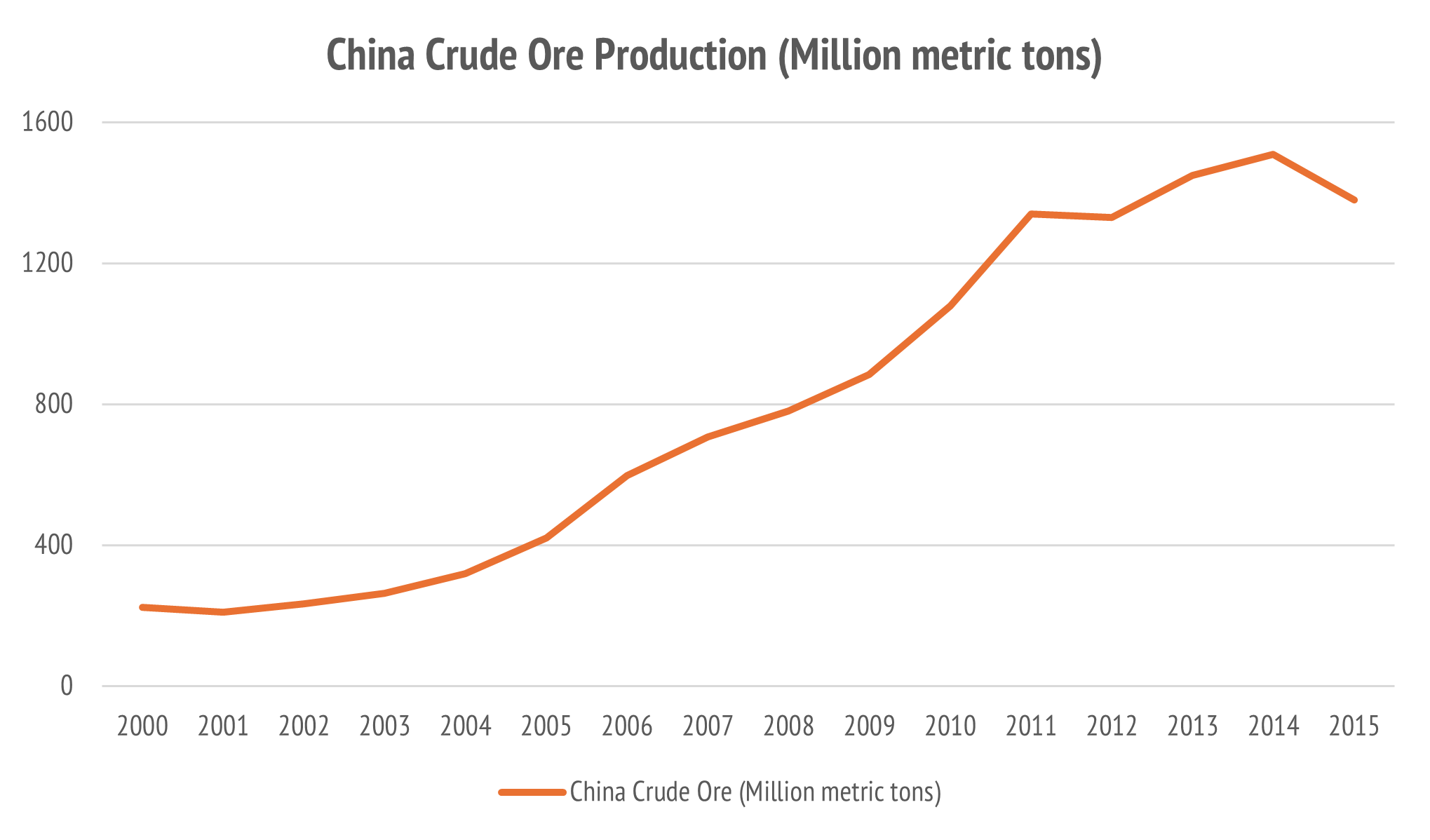

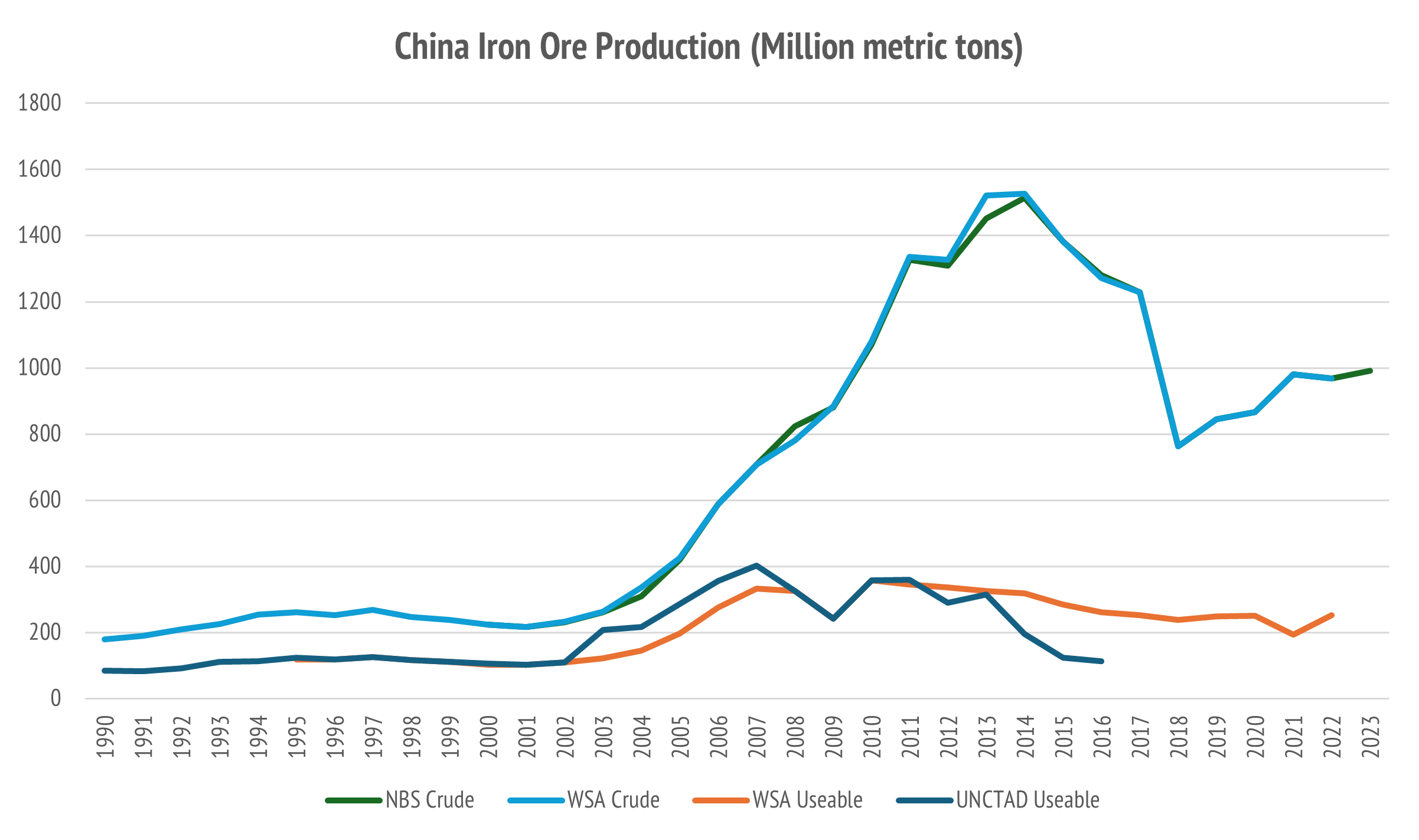

Here is the official National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) crude iron ore production data.

I have no doubt this upward marching line is correct. That is after comparing this data to that from the World Steel Association (WSA) and cross-checking the global iron ore data with pig iron and direct reduced iron production.

On paper, it looks like Chinese iron ore production is a big deal, so why dig deeper?

The problem is the meaning of that vague term "crude iron ore".

What is crude iron ore?

In most data agencies, statisticians recognise the importance of grade when adding up tons of material, whether in the ground, in a sling bag on a truck, or an ore train.

The grade of iron ore you need to run a blast furnace to make pig iron is 62%. This can be varied through blending, and other means, but you need to be close to that figure.

Standard iron ore benchmarks for pricing recognize this by stating the grade alongside the price, such as 62% Iron Ore Fines. Similar things happen in the lithium market.

On occasion, such as for lithium ten or twenty years ago, the statistical agency may ignore the grade differences and add up inequivalent tonnes of different grade ores. This is what the US Geological Survey (USGS) did with lithium, until they fixed it.

This has also been happening with China mined iron ore.

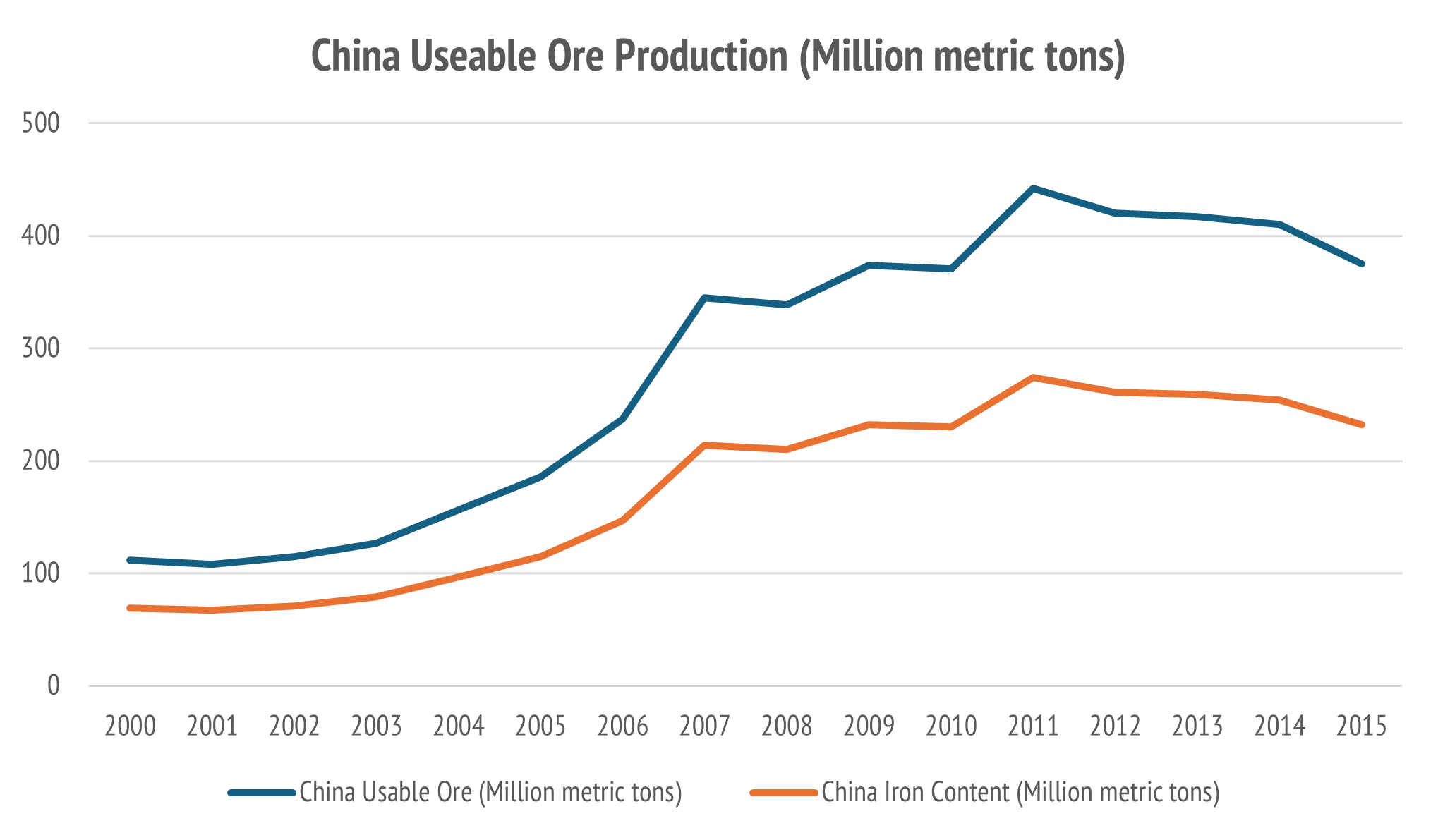

In 2017, the USGS published a report USGS revision of global iron ore production data, to explain how the Chinese crude ore production must be adjusted for grade.

This anomaly distorted global iron ore production data by 10%.

The USGS corrected their data for 2000-2015 using China Iron and Steel Assocation (CISA) numbers, the NBS "crude iron ore" and their adjusted "useable ore".

If you eyeball the above two charts, you can see that the impact is massive.

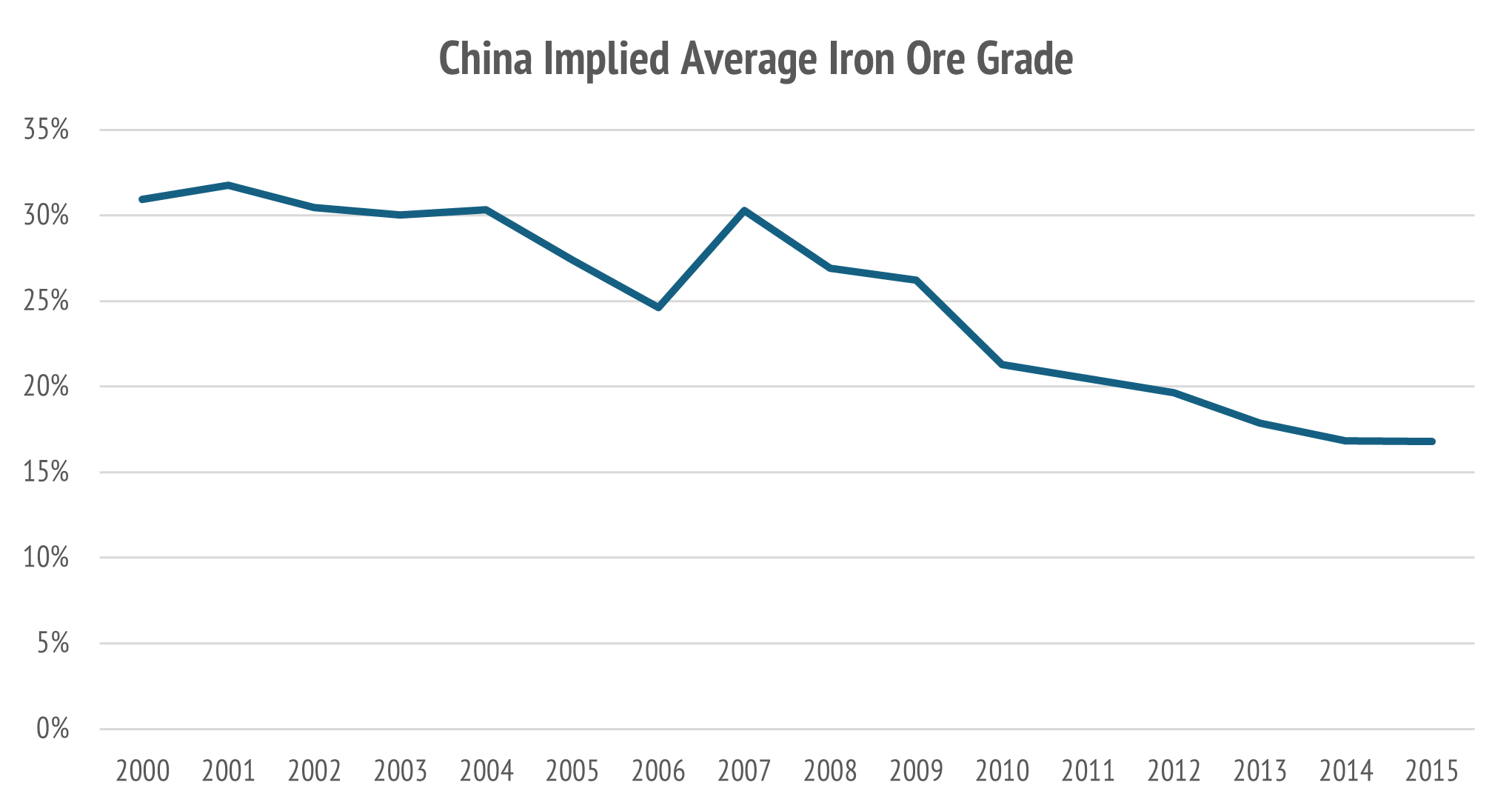

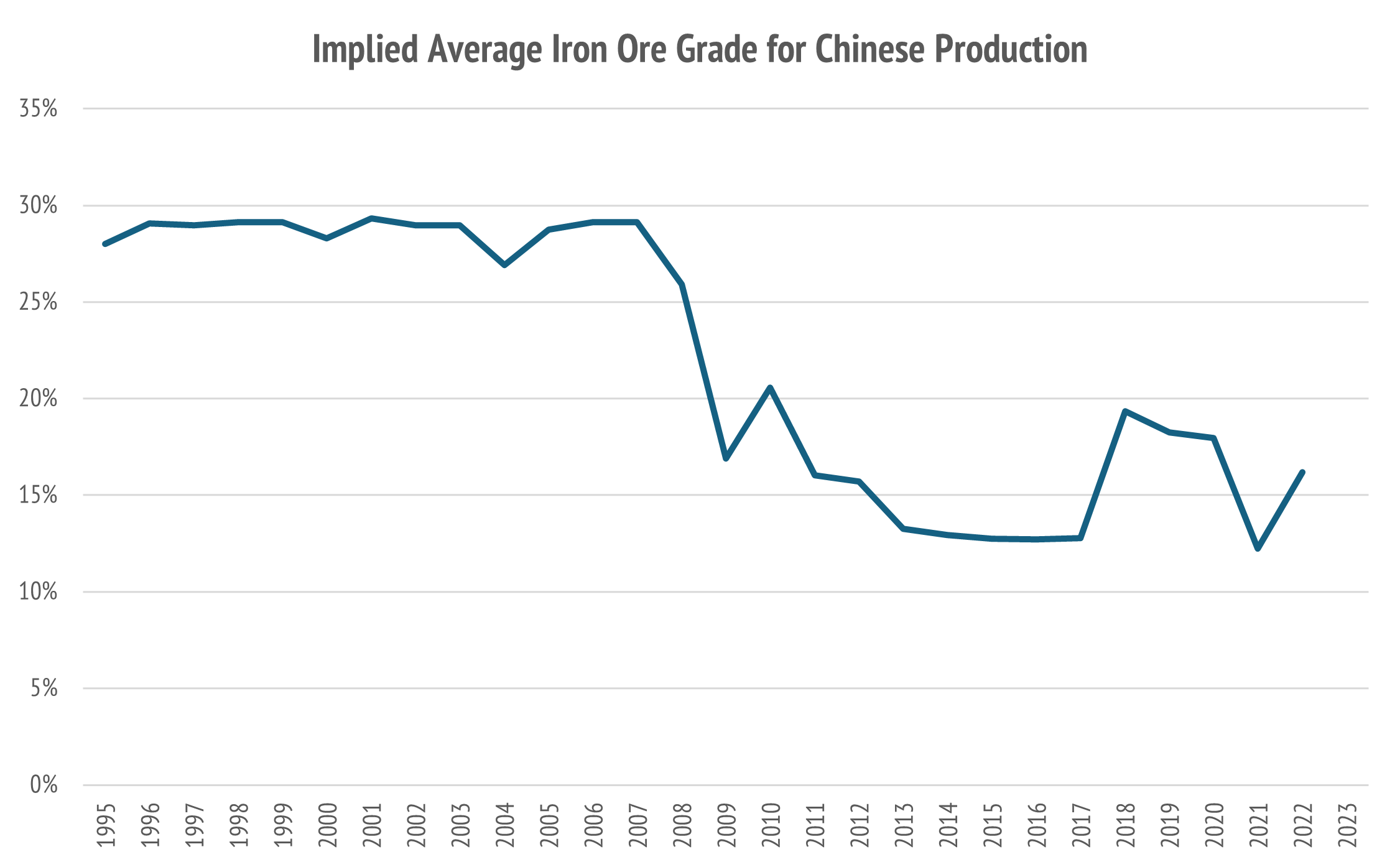

Translating this into a grade chart, the driving factor is very clear.

This impacts the marginal cost of production in China. Whereas a 30% grade needs around a 2x uplift through beneficiation, a 15% grade needs a 4x uplift.

In simple terms, China needs to move four tons of rock for every one ton that an Australian miner needs to move in the Pilbara.

They also need to beneficiate that four tons to one!

This is expensive, so Chinese costs are likely at least four times greater per unit of useable ore, which is what a blast furnace operator will buy to produce pig iron.

Extending the data correction

In seeking to extend this data correction back in time I dug into the origins of the correction and found that the United Nations agency UNCTAD had a program to correct this, which is now defunct, but seems to have started in the early to mid 1990s.

This data shows up, along with a continuation of the series in the WSA Steel Yearbooks.

There are some revision anomalies in the WSA data, but one can reconstruct their method by reconciling the pig iron production in China to the ore consumed. China pig iron is about 4% carbon by weight, but you can make the adjustments to estimate grade and useable ore.

Once you make this correction, it is obvious that China has not been growing domestic iron ore production in any meaningful way.

I don't think this is a nefarious plan from China. They have a wide diversity of iron ore mines. Some are rare earth mines that produce iron ore as a byproduct.

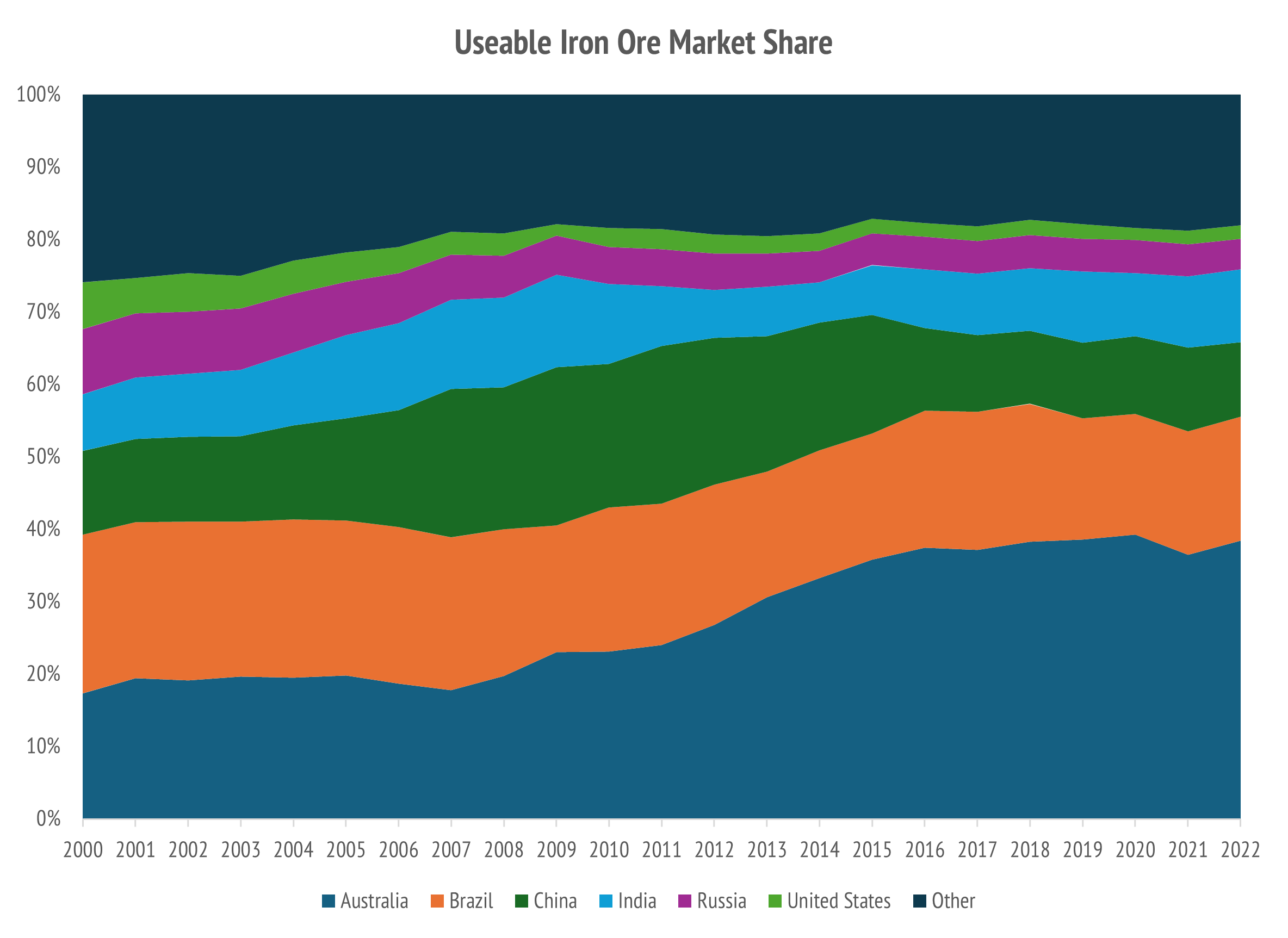

Impact on global market shares for iron ore production

Once you adjust the data properly, you get a different global market share picture.

China appears with 40% market share in some data sets that have not been corrected for this anomaly. The real figure is about 10%, similar to India, with Australia at 38%.

The true grade picture for China is also informative.

The recent grade values have been around 15%, or less than one quarter of the Pilbara.

Investment conclusion

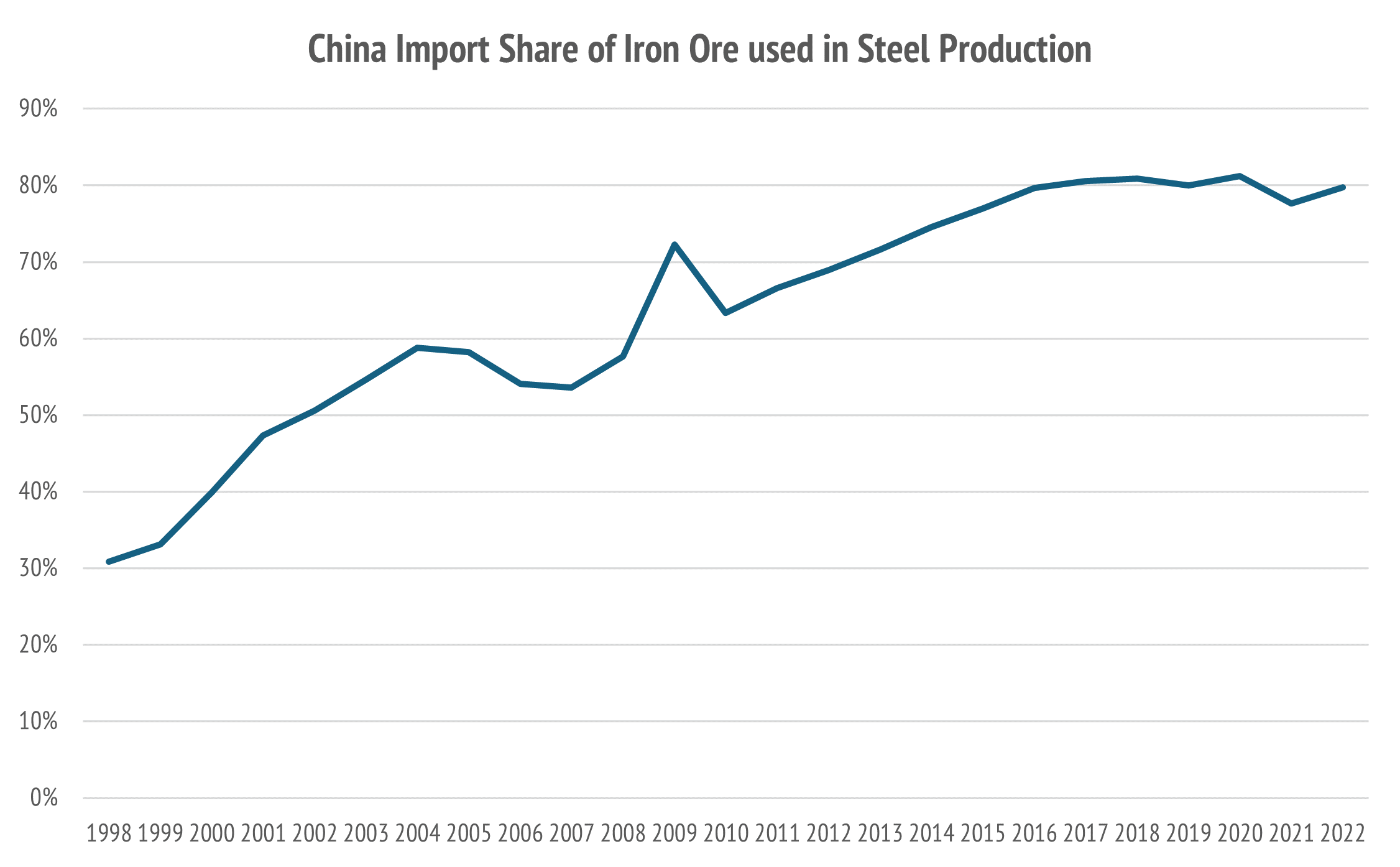

The most telling conclusion is the heavy import reliance of China.

Clearly, China is very dependent on Australia, Brazil, and India for its steel production.

The import share seems to have topped out at around 80% as China hit Peak Steel. The assumption has been that the iron ore price would collapse, but the domestic industry will likely provide price support at a level some four times Australian costs.

We think that the ballpark range is US$80-100/tonne.

The iron ore price is now in that territory.

A rebound from these levels seems likely but note that iron ore is ex-growth. There is growth in Indian steel production, and in the Middle East, but none in the West.

The main game is to manage the industry for profitability.

Equally, the industry should be managed for good relations with the major buyer.

The risk for Australia, and India, being Quad partners, is that China turns to Brazil, and to the emerging province of Simandou in Guinea, East Africa.

Australia will lose if we do not manage the China relationship well.

I will mention specific stock ideas in a forthcoming wire.

5 topics

8 stocks mentioned