The coronavirus pandemic and the economy - a Q&A from an investment perspective

Along with the horrible human consequences, the coronavirus pandemic is having a huge impact on the way we live and as a result investment markets. This has raised a whole bunch of questions: why does a big part of the economy have to go into “hibernation”? how long might it be for? how big will the hit to the economy be? what does it mean for unemployment? why is it so important for governments and central banks to protect

businesses and workers? can we afford all this stimulus? This note provides a simple Q&A for most of the main issues from an economic & investment perspective. To the extent simple answers are possible in this environment!

Why do we need the shutdowns?

This is a medical issue, but it drives everything that follows. The answer is simple. Something like 15% of those who get coronavirus need hospitalisation and 5% need intensive care. And this is not just elderly people. And there is little to no community immunity to it. So, if a lot of people get it at once the hospital system can’t cope and the death rate shoots higher. Italy shows this with a death rate of 11.7%. So, unless we want to see the same surge in deaths as Italy we have to “flatten the curve” of new cases so the hospital system can cope. And to do this we have to practice social distancing which means meeting up with as few as people as possible which means staying at home wherever possible. This in turn means a big part of the economy gets shutdown.

Which sectors of the economy are most impacted?

Roughly 25% of the economy is being severely impacted and

this covers discretionary retailing, tourism, accommodation,

cafes, clubs, bars and restaurants, property and various

personal services. But there is also likely to be a flow on to

construction and parts of manufacturing as uncertainty leads to

less housing construction for example. Only about 20% of the

economy - communications, healthcare and public

administration - will really get a boost.

How big will the hit to the economy be?

It’s impossible to be precise, but if 25% of the economy

contracts by 50% with other sectors offsetting each other, that

will drive a 12.5% detraction in economic activity mainly in the

June quarter which is basically what we are assuming. This will

the biggest hit to the economy seen since the Great

Depression. Of course, if this leads to collateral or second

round effects as, for example, businesses and households

default on their loans the impact could be much greater and

longer.

But why all the talk of hibernation?

The hibernation concept is a good way to look at it. As a result

of the shutdown many businesses are seeing a massive loss in

their sales and some must partially, or in many cases fully,

shutdown until the virus is contained and the shutdowns can

end. But rather than shutdown forever the best outcome is for

them and their employees to effectively go into “hibernation” for

a period so they can go back into business and resume their

normal lives once the virus is under control but without being

encumbered with so much more debt and rent arrears, etc, that

they go bust anyway.

Why the need for massive government support?

This is where government and central bank action comes in.

Since coronavirus became a global pandemic last month and

countries progressively ramped up social distancing policies,

governments and central banks have swung into action to help

economies weather this storm. This is absolutely necessary.

Such support is unlikely to stop a recession or depression like

contraction in the economy. But it’s needed to minimise the

collateral or second round impacts of the shutdowns and enable

the economy to start up again when the threat from the virus

abates. Australia has announced three fiscal stimulus tranches

now totalling around $200bn or 10% of GDP, which is nearly

double that of the GFC stimulus. Other countries have also

announced massive stimulus with the US just signing off on one

package worth $US2 trillion and now talking of another. The

policy response is now of a magnitude that it’s starting to tip the

risk scales against some sort of long depression/recession.

How will it be paid for?

Simple, the Government will issue bonds & borrow the money.

But can we afford such a surge in the deficit and debt?

First, to stress it’s absolutely necessary. The hit to the economy

from the shutdowns could be 10 to 15% of GDP. This requires a

similarly sized stimulus program to offset it otherwise we risk

immeasurable collateral damage to the economy and people’s

lives (causing an even bigger budget deficit).

Second, it makes sense for the public sector to borrow from households and businesses at a time when they are stuck at home and can’t spend due to the shutdowns or won’t spend due to uncertainty and for the Government to give the borrowed funds to help those businesses and individuals that are directly impacted. Using the funds to subsidise wages is a particularly smart move as it keeps people employed and keeps them linked to their employer. The trick is to curtail the stimulus once the economy bounces back otherwise the competition for funds will boost interest rates and create problems for the economy. So, the support programs are set to end after 15 months.

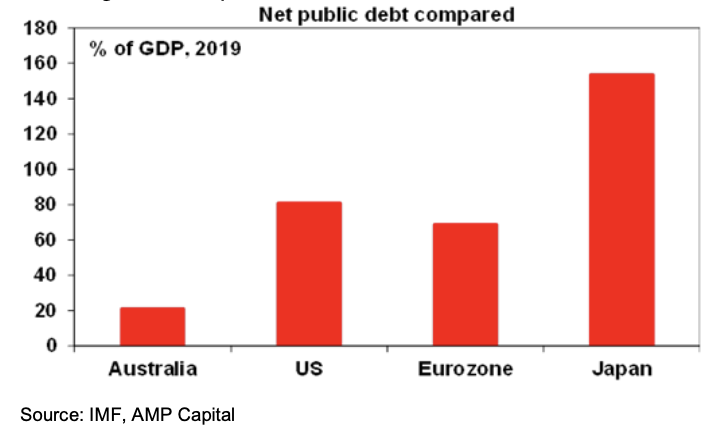

Third, Australia’s public debt is relatively low. Net public debt as

a share of GDP is a quarter of what it is in the US. So, Australia

has far greater scope to do fiscal stimulus than other countries.

Fourth, the cost of borrowing for the Federal Government is very low at just 0.25% for three years and 0.75% for ten years.

Finally, the budget blowout may risk a downgrade in Australia’s AAA sovereign debt rating, but Australia’s public finances will still look better than others. And I would rather a rating downgrade than a deep depression/recession any day.

When the dust settles Australia will be left with higher net public

debt at maybe around 45-50% of GDP. It will be the price we

paid to (hopefully) minimise the loss of life from the virus and at

the same time minimise the hit to people’s livelihoods from the

shutdown. This may necessitate forgoing the next round of tax

cuts or a new deficit levy. And it may put a burden on future

generations as wartime spending did. But I reckon that’s a cost

most Australians are prepared to wear.

Why is monetary stimulus necessary? Low interest rates won't get us to spend when we are stuck at home

Yes, people can’t spend much now, but as with government

stimulus much of the central bank easing has been aimed at

“protecting” the economy. This has three key elements:

- lowering interest rates to make it easier for borrowers to service their loans – eg, the RBA has cut interest rates and targeted lower bond yields to cut long term borrowing costs;

- pumping money into financial markets to make sure they keep functioning. As the crisis intensified bond yields perversely started to rise (as fund managers had to sell their liquid winning assets to meet redemptions) and corporate borrowing rates surged as investors feared defaults so the Fed pumped money into the US bond and credit markets to push yields back down. The ECB has done something similar in Europe by buying Italian bonds; and

- ensuring cheap access to funds for borrowers – eg, the RBA has provided funding for banks for 3 years at 0.25% which has enabled the banks to cut rates and offer debt payment holidays. The Fed is even undertaking direct lending.

How does quantitative easing help the government stimulus measures? Won't it cause inflation?

Quantitative easing – which the RBA has now joined the Fed,

ECB and Bank of Japan in doing - involves using printed money to buy government bonds in order to help keep interest rates

down. The central bank buys these bonds in the secondary

market (eg from fund managers) so it’s not directly providing the

money to the government and those bonds must still be paid

back when they mature. So, it’s not really “helicopter money” –

which would see the RBA print money and give it to the

Government which it would then spend. But of course, it is

aiding the government’s stimulus program by helping to keep

bond yields down. In the meantime, the balance sheet of the

RBA will rise as it holds more bonds, but this is not a major

issue unless inflation starts to rise due to all the extra printed

money in the system. The Fed, ECB and Bank of Japan have

been doing QE for years with no rise in inflation, so the RBA

has a long way to go before it becomes a problem. Put simply

there is no magical right or wrong level for the RBA’s balance

sheet so if you are worried about it, just ‘chillax’.

How high will unemployment go?

We see unemployment rising well above 10% in the US

(possibly to even 25%). But in Australia, there is a good chance

that the Government’s wage subsidy scheme will keep up to 6

million workers in the most affected parts of the economy in a

job and this may contain unemployment to below 10% here.

The decline in unemployment though will likely be slow though

depending on the shape of the recovery.

Will the recovery in the level of economic activity look a V, a U or an L?

Much will depend on how long it takes to control the virus. An L

shaped (or no real) recovery is unlikely given: evidence that

shutdowns will slow down the number of new cases as

occurred in China and may now be starting to occur in Italy; the

chances of a medical breakthrough; and all the stimulus which

should aid some sort of recovery. By the same token a quick V

style recovery is unlikely given that absent a quick medical

solution the shutdowns will be phased down only gradually (with

international travel being perhaps the last restriction to be

removed). This suggests a U-shaped recovery is most likely.

Could anti-virals or a vaccine improve the outlook?

Put simply yes. A study of past epidemics and the medical

response to them by my colleague Brad Creighton shows an

ability of governments working with scientists and the medical

community to rapidly speed up the development and

deployment of anti-virals and vaccines. There is now a massive

global effort on this front and some drugs are promising. So, it’s

not out the question that there is a breakthrough enabling a

quicker relaxation of shutdowns.

When will shares recover?

The historical record of share markets through a long litany of

crises tell us they will recover and resume their long-term rising

trend. The massive global policy response to support

economies in the face of coronavirus driven shutdowns is

starting to tilt the risk scales against a long depression scenario.

This is why share markets have started to get some footing

over the last week or so after seemingly being in free fall for a

month. Key things to watch for a sustained bottom are: signs

the number of new cases is peaking – with positive signs

emerging in Italy; the successful deployment of anti-virals; signs

that corporate and household stress is being successfully kept

to a minimum – too early to tell; signs that market liquidity is

being maintained and supported as appropriate by authorities –

this has improved; and extreme investor bearishness – investor

panic is already evident but it can get worse.

4 topics