The dawn of a new UK infrastructure revolution

A Historic Victory

On Thursday 4 July, the UK held a general election. After 14 years of Conservative Party rule, the Labour Party under Sir Keir Starmer won a landslide victory. As the polls had roughly predicted, the Labour Party won 411 seats out of a possible 650. Not since ex-Prime Minister Tony Blair (around 30 years ago in 1997) has Labour won such a large majority (when Blair under the campaign moniker of New Labour won 418 seats out of a possible 659).

In the UK parliamentary system, the House of Commons has ultimate legislative control. It’s the result in the House of Commons that matters. The House of Lords can’t block a proposed bill from passing but can delay it for a year with amendments. Generally speaking, the size of the majority in the House determines the size of the mandate for change. The Tony Blair led New Labour government was a consequential one, and this current Labour government under Sir Keir Starmer has a similarly large mandate. From an investment perspective, what might change?

Key Policy Shifts

When Tony Blair won in 1997, his party manifesto made education the number one priority and rebuilding and enlarging the National Health Service (NHS) a key priority. Aside from writing eloquently, Tony Blair was effective and has been the longest continuously-serving Labour Prime Minister ever. In Blair’s first term, he signed the Belfast Agreement, passed the Human Rights Act, introduced a national minimum wage, reformed the health and education sectors with market-based measures, and ran one of the most redistributive set of policies the UK has ever seen. After another landslide victory in 2001 (another 412 seats won), Blair significantly improved the quality of NHS and education services after increasing taxes. At no point, though, was housing a major electoral issue for New Labour.

Sir Keir Starmer’s priorities are different. In a different, modern time, Labour’s policy mix has shifted. The recent Labour Party manifesto emphasised the need to kickstart growth. In order to achieve this growth goal, the Labour Party is focused on “reforming the UK’s planning rules to build railroads, roads, labs and 1.5 million homes we need [as part of] a new 10-year infrastructure strategy.”

Rachel Reeves became the first female chancellor of the exchequer (equivalent to Treasurer in Australia). In her first speech entitled Immediate Action to Fix the Foundations of our Economy, Reeves emphasised that:

“The story of the last fourteen years has been a refusal to confront the tough and responsible decisions that are demanded. This government will be different, and there is no time to waste. Nowhere is decisive reform needed more urgently than in the case of our planning system. Our antiquated planning system leaves too many important projects tied up in years and years of red tape before shovels ever get into the ground. We promised to put planning reform at the centre of our political argument – and we did. We said we would grasp the nettle of planning reform – and we are doing so…Today, alongside the Deputy Prime Minister, I am taking immediate action to deliver this government’s mission to kickstart economic growth; and to take the urgent steps necessary to build the infrastructure that we need, including one and a half million homes over the next five years.”

The primary way for this Labour Government to generate economic growth is clear. It is to build. To build homes and infrastructure.

Overcoming Past Challenges

The natural question to ask is whether this central government can achieve this goal to build when others have failed. The policy of legally mandating the country to build 300,000 homes, on average, for the next 5 years would represent a significant uplift in construction activity. For the last few years, the UK has built around 190,000 homes per year on average. It would represent a significant 50% uplift in activity.

To understand whether this government can achieve this lofty goal when others couldn’t, history may provide us with some clues. At its core, previous governments short of large majorities have struggled to find the moral courage to fight against vested local interests, or didn’t prioritise housing reform. Tony Blair’s New Labour, for instance, did not list housing policy in its top 10 policy objectives. But armed with an electorate now fed up with unaffordable house prices and rents, Sir Keir’s government is aware of the local political opposition that will ensue and committed to overcoming it.

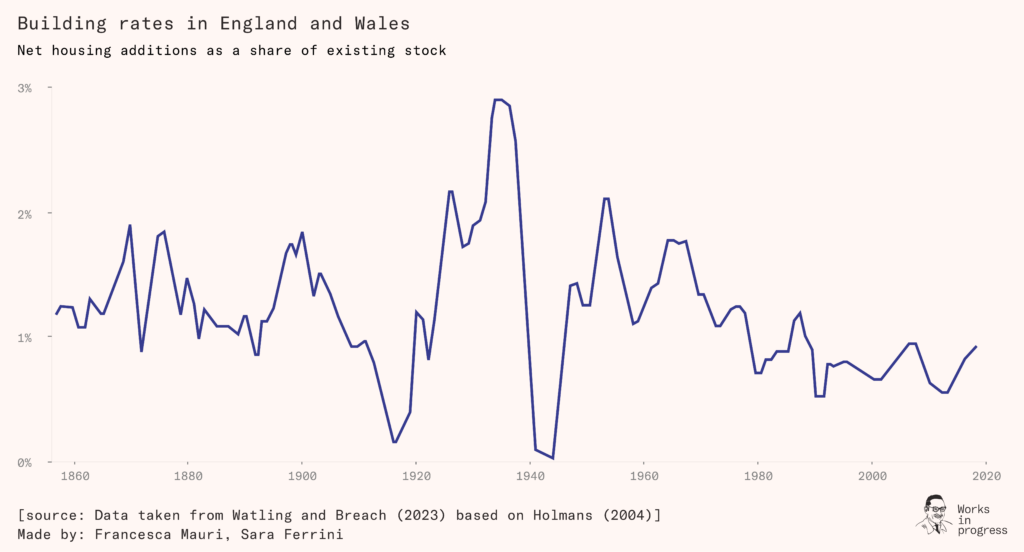

For our purposes of understanding, we can explore a brief history of UK housing policy starts after World War II. The following chart shows the pace of home building in the UK over time:

Source: Works in Progress

There are a few clear patterns in the chart above. The first is that building activity during each of the world wars drops significantly as soldiers are recruited to fight and resources shift towards war efforts. The second is that home building activity increases significantly following each world war. As soldiers returned, they repaired and rebuilt damaged homes. The third is that, following World War II, there has been a gradual and secular decline in home-building activity. What can explain this decline?

The core reason for the decline is government regulation and local political opposition to urban sprawl, as the invention of trams and other forms of transport allowed cities to spread. In 1947, following World War II, the Labour Party passed the Town and Country Planning Act. This law prohibited all private development without explicit permission. Private development was envisaged to be replaced by state-directed building of government-mandated “New Towns.” But the government struggled to build enough homes following the destruction of World War II.

The Conservative government put poor housing conditions at the centre of their 1951 campaign, against Labour’s policy of state control and rationing. The policy was electorally successful. By abolishing building licenses while simultaneously increasing funding for public housing, Britain built more houses than ever (even to this day). Between 1951 and 1955, the UK built 1.5 million homes.

After this period of rapid building, however, the politics changed. Given local interests concerned by urban sprawl, the UK government introduced a new policy allowing for an area to be designated a “green belt.” Under this policy, once a piece of land was designated part of a green belt by a local government, it would be nearly impossible to develop. Rural counties, all of a sudden, were effectively given a veto over further housing development.

This combination of the green belt policy and the death of building government-mandated New Towns resulted in the end of fast rates of home building growth post World War II.

The Conservative government of Harold Macmillan in 1962 and the Labour government under Harold Wilson in 1970 both put in place home-building targets. While the ambitious targets of 400,000 – 500,000 homes per year was not achieved, there was a significant bounce in homebuilding from 1962 onwards. Since then, though, local opposition from green belt constituencies has disincentivised central governments from dealing with the issue.

The Blair Government didn’t explore land reform until 2004. By that time, however, it was late into Blair’s term, who was about to lose his large majority in the 2005 election. Local opposition frustrated his task of reform. According to Works in Progress, “the [Blair] Labour government did not give these organisations the power to seriously overcome the opposition of local residents and administrations…So, after Labour lost the 2010 general election, regional planning was immediately scrapped.”

Capitalizing on the New Economic Landscape

It’s within the context of house prices rising to historic multiples of income and the cost of living getting significantly worse that the current Labour government has been voted into power.

What is the current Labour government seeking to do to change the situation? First, a new commission will be set up to change the existing laws. The central government will also provide local governments with 300 planning officers across the country to speed up the development of new town developments. Additionally, the development of brownfield and greyfield sites will be accelerated. Ministers will be given more power under the existing laws to override local government decisions. While already existing, these central powers had not been used previously but the political climate has changed. The Deputy Prime Minister is also seeking to change how green field sites are defined by local governments.

While a large majority doesn’t guarantee these changes will be effective, central government focus in the past on home building has led to phases of increased construction activity. We’ve never seen such a holistic approach to reforming home building in the past. It hasn’t been since the late 1960s that a government campaigned on building more homes as part of their mandate. Our judgment is that, at worst, we’ll see a significant uplift in activity like in the 1960s and at best, the UK will begin a new phase of housing and infrastructure development for the next 10 years. The risk-reward of investing in UK infrastructure and home builders, as a group, is extremely skewed to us given how cheaply they currently trade. After being battered by higher interest rates, the pricing of the group doesn’t reflect any upside from here.

2 topics