The end of a 25-year bull market

An increasing number of data series have been turning negative for Australia’s housing market. Auction clearance rates, building approvals, housing credit growth, and even house prices themselves appear to have topped. Anecdotes are popping up of units being resold far below their original purchase value, or with significant incentives offered to potential buyers. A growing chorus of commentators and investment banks are now calling the end of the 25-year property boom. But if you’ve been around for a while, you’ve probably heard all this before. So, is this the real thing? Or just more noise to filter out? To find out, we asked the experts for their take on the current situation.

Biggest falls in over a decade

Shane Oliver, Chief Economist, AMP Capital

I was lucky. My wife and I bought our home in 1995 when mortgage rates were still double digit, household debt was low and house prices were low relative to incomes and the Australian residential property market was to embark on a multi-decade bull run. Now it’s the opposite: rates are low, but debt ratios are world beating and home price to income ratios are excessive – particularly in Sydney and Melbourne – warning of a period of weakness.

In fact, with supply picking up and banks tightening lending standards prices are starting to soften. The fall in property prices in Sydney and Melbourne likely has further to go and will likely prove to be more severe than the soft patches seen around 2005, the GFC and 2012.

Our base case, with a 70% probability, is for prices in Sydney and Melbourne to fall another 4% or so this year, another 5% next year and around 2-3% in 2020. Great if you are a home buyer, not so good for sellers. Other cities are a bit different though – having already seen extended price weakness Perth and Darwin home prices are at or close the bottom, other capital cities are likely to see moderate growth having not had the boom that Sydney and Melbourne saw and regional centres are reasonably attractive helped by much higher rental yields. Overall, Sydney and Melbourne are likely to see a top to bottom fall of around 15% spread out to 2020, but for national average prices the top to bottom fall is likely to be around 5%.

In the absence of much higher interest rates or unemployment a property crash is unlikely, but not knowing how severe the tightening in bank lending standards will get the risks cannot be ignored. Our downside scenario with a 20% probability would see a 20% decline in Sydney and Melbourne and a 10% drop nationally.

The key for investors – apart from looking for good properties in well located areas with good rental prospects! – is to sell high and buy low. So, avoid the recent boom time cities of Sydney and Melbourne and focus on high yielding capital cities and regional centres that have lagged and are less likely to be affected by a restriction in lending going to high debt to income households.

The data that matter

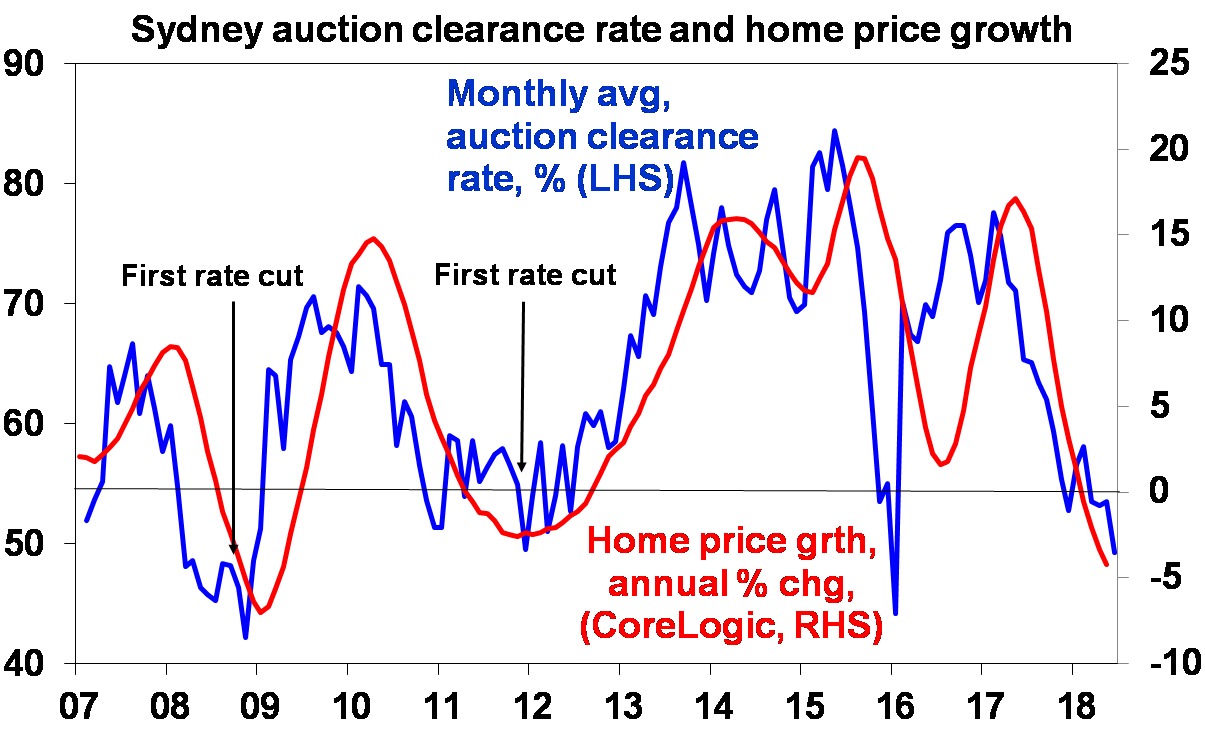

Weekend auction clearance rates for Sydney and Melbourne are my favourite to watch. They are not perfect, but they give a timely guide to what is happening. So far, they are indicating gradual declines consistent with our base case. See the chart for Sydney. A sustained drop in clearance rates into the low 40s or worse would signal steeper declines in prices.

Source: Domain, AMP Capital

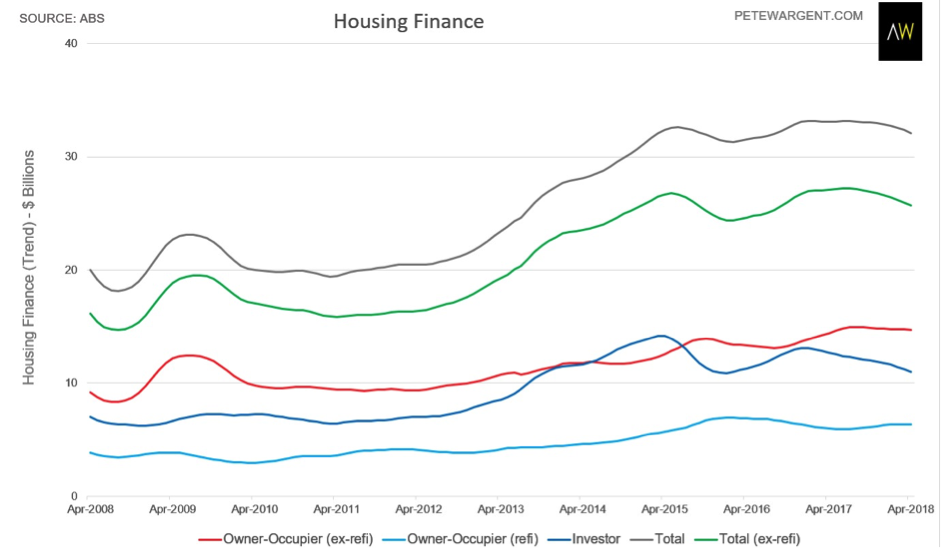

More broadly, monthly housing finance commitments data from the ABS should be watched closely as a guide to how severe the tightening in bank lending standards is becoming. Housing credit is currently growing at around 6% year on year. This is likely to slow but the debate is by how much.

A slowdown to around 3-4% would be consistent with our base case, but anything more could be warning of a downside scenario for home prices.

Extended price falls across capital cities

Alex Joiner, Chief Economist, IFM Investors

My base case scenario for residential property is further ongoing declines in prices at the capital city median level. I expect somewhere in the range of 3 - 5% per year, but for an extended period.

Affordability has seemingly hit a limit after the Australian household sector has capitalised both structurally (as inflation targeting was adopted) and cyclically low mortgage rates into prices. Indebtedness of the sector is consequently at a record high.

Price levels have got to the point that the marginal buyer is wary of taking on such a large quantum of debt at this point in the cycle. Further at the margin macro-prudential measures and tighter credit conditions are eroding the household sector’s ability to leverage already – and seeing current price levels difficult to sustain.

Ideally, the Reserve Bank will raise rates in the coming twelve months. This will put further downward pressure on prices that will in part be offset by strong population growth and better household incomes. The latter being a prerequisite for the RBA to move in the first place.

Any downside risk to the property market would come from a rise in the unemployment rate as forced selling occurs. This is not a consensus view and would likely occur due to an external shock or a potential policy error by the Reserve Bank, such as a premature or overly aggressive move higher in rates. On the latter, note that since the RBA started targeting inflation, it has never begun a tightening cycle while prices have been in decline. Doing so would be a new paradigm that does entail some risk.

I’d think the base case is a 4 in 5 chance, with a more disorderly decline in prices a 1 out of 5.

Timely data is the key

Outside of price series themselves, the standard indicator to watch is the auction clearance rates as these, despite being noisy, are the timeliest data. This shows only how well the market clears, not if buyers have come to sellers or vice versa. But normally clearance rates correlate well with prices in Sydney and Melbourne, where a higher proportion of properties are sold on the market. Indeed an increase in the proportion of private sales and not auctions is somewhat of an indicator as real estate agents become more cautious.

Monthly official data including housing finance and credit figures are also key as to future and current activity in the property market. Some of the softer indicators are also useful, the WBC-MI ‘Time to Buy a house’ index and price expectation surveys amongst others give a good read on sentiment towards the sector.

Another ‘soft’ indicator is just how much developers, investor and lobby groups and real estate agents become more vocal in the media suggesting disaster for the economy is looming should the property sector soften even marginally.

Big falls ahead if ALP win

Pete Wargent, Director, Wargent Advisory

Some regions of Sydney have already corrected by more than 10 per cent in pockets, with tighter lending standards now biting, especially for investors. At the other end of the spectrum, apartment prices in the desirable eastern suburbs have come off only marginally to date.

With the usual caveat that we’re only active in a relatively small number of suburbs, mainly in the inner suburban market, our base case for Sydney is a peak to trough decline of about 10 per cent before the market stabilises. Some markets, including houses in outer western Sydney could experience a larger drawdown.

There is, however, a further downside scenario to watch out for. If the ALP wins the next federal election and implements proposed reforms to negative gearing and the capital gains tax discounts, we see prices across the state down by a further 9 per cent for houses and 9 per cent for units. In some sub-markets the impact will be more acute still.

In our recent report on negative gearing and CGT, co-authored with RiskWise Property Research, we assessed the impacts of the proposed reforms, and the consequences of taking a blanket approach to their implementation throughout the country.

The ALP has previously proposed to limit negative gearing to new rental dwellings and to halve the CGT tax discount from the current 50 per cent to 25 per cent, the stated intention being to level the playing field for first homebuyers competing with investors, improve housing affordability and strengthen the budget position through limiting these subsidies.

However, the landscape in the Australian property market has changed and this needs to be taken into consideration.

From the second half of 2017, the risks associated with the residential property market increased significantly, and the proposed reforms need to be assessed thoroughly across all geographical areas. Credit restrictions and tighter lending standards have had a direct impact on investors in the Australian housing market.

As a result, dwelling prices in Sydney and Melbourne showed a decelerating growth rate, followed by price reductions in Sydney and, to a lesser extent, Melbourne.

Declining dwelling prices (or price deceleration in some regions) would lead to a reduction in dwelling commencements and deteriorating rental affordability in some locations.

Our analysis also demonstrates that there would be some distortions in the investor market, with the creation of primary and secondary markets for investor stock if subsidies were limited to new housing prospectively, the thinner market on resale potentially increasing the risk of investing in new dwellings.

Our report concludes that while there would be some positive initial impacts on housing affordability, these would only be sustained in the largest capital cities if appropriate policies are implemented to encourage the supply of owner-occupier suitable housing in addition to investment units.

Housing supply, particularly dwellings in the middle-ring capital city suburbs that are suitable for family cohorts, are a crucial factor in resolving housing affordability issues.

The data to keep an eye on

In the short term, continue to watch housing finance closely. Total trend housing finance continued to soften in April 2018, down from $33.2 billion at the market peak in January 2017 to $32.1 billion, a total decline to date of 3.2 per cent.

Total home lending is at the lowest level in around 1½ years, and the timeliest indicators suggest that there was likely a further deterioration through the months of May and June.

There's no doubting the drivers of this. Back in the first half of CY2015 the monthly trend for investment loans was temporarily tracking above $14 billion per month. But the squeeze is now on, with that monthly figure now down to $11 billion, and falling.

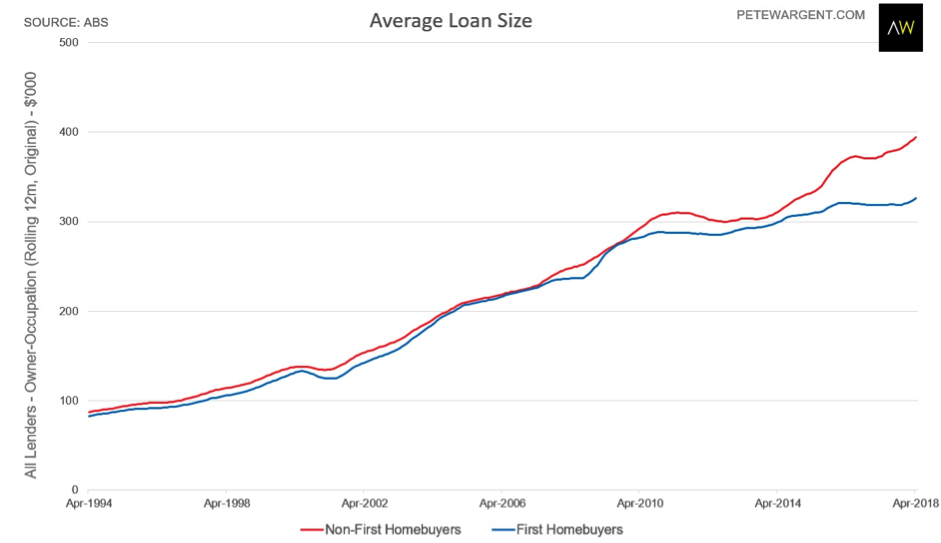

One interesting point of note is that lenders are quietly taking the brakes off for the upgrader cohort, with the derived average loan size for non-first homebuyers rising to $410,400 in April, comfortably the highest level on record.

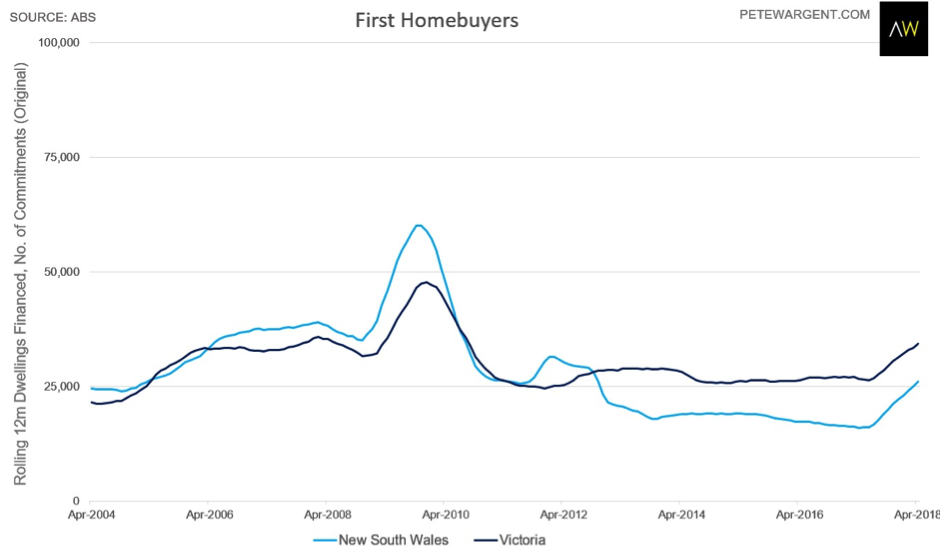

Furthermore, first homebuyer incentives are drawing first-timers back in to the market. April is typically a seasonally soft month for market activity, but the annual number of loans written to first homebuyers is up by 63 per cent year-on-year in New South Wales and 29 per cent year-on-year in Victoria (albeit from depressed levels in Sydney's case).

Given the considerably softer market conditions, first homebuyers should do their due diligence, be careful not to overpay, and must not stretch beyond what they can comfortably afford to repay.

Overall, there is now a good deal more buyer caution in the housing market.

Almost all construction indicators from dwelling commencements, to new home sales, to finance for land sales are now pointing south, and we expect residential construction to slow in H2 2018 and beyond.

Indeed, in our recent wire, Requiem for a Construction Bubble we demonstrated how the construction sector is at its most bloated level in approximately a century, accounting for nearly 10 per cent of the entire workforce.

We envisage a sharp slowdown in construction activity and the associated multiplier, and see this as the greatest risk for the economic outlook.

2 topics

2 contributors mentioned