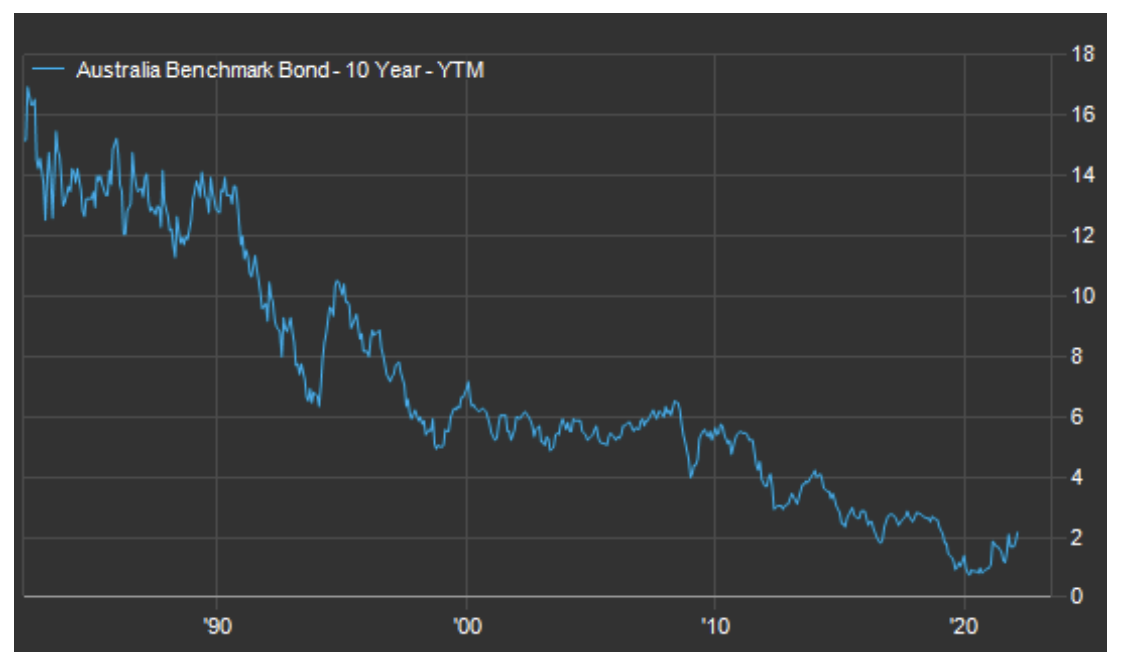

The end of a four-decade bull market (and where to invest now)

The yield on the Australian 10-year government bond has reached 2.7%, its highest level in more than three years, as central banks around the world move to increase cash rates to stymie inflation.

On Wednesday last week, the US Federal Reserve announced its first 0.25% interest rate hike since 2018, while the Bank of England has already lifted rates three times since December, with its cash rate now at 0.75%. Meanwhile, Australia's cash rate still sits at 0.10%.

According to Perpetual Asset Management's Michael Korber, the firm's managing director of credit and fixed income, we have now reached the end of a four-decade-long bull market in bonds.

"In 1982, the yield on a 10-year government bond reached towards 17%. By contrast, for all the talk of rising yields over the past six months, the 10-year has only just established itself above 2% consistently in the last few weeks," he said.

Korber joined Perpetual in August 2004 and has over 39 years of experience working within credit markets. He's also worked for Macquarie and Westpac. And while he enjoys sailing and travel, he says his true love is investing.

"Away from my working world of fixed income, I find a lot of reward and intellectual challenge investing in a few micro-caps and private companies across a range of industries. Maybe my breadth of interests accounts for the love of diversification that’s at the heart of every good, fixed income portfolio!" Korber said.

And now, with expectations of an accelerated tightening regime, not to mention escalating geopolitical tensions and supply chain disruptions, credit and fixed income are starting to look a lot more attractive, he said.

Within this new market environment, Korber believes that a diversified portfolio of floating-rate corporate debt and shorter-dated fixed rate bonds can provide investors with much-needed capital stability, liquidity and income.

In this wire, he provides a brief education on floating and fixed-rate bonds, how these perform in inflationary (and deflationary) environments, as well as where he is finding opportunities as we enter into the first bear market for bonds in four decades.

.jpg)

Bonds and term deposits have fallen out of favour with many investors over the past few years, with many shifting towards riskier assets in their search for yield. Is the 60/40 asset allocation model dead? Why does fixed income still have a place in investors’ portfolios?

The 60/40 split is only as “dead” as it has ever been. The right asset allocation mix remains a function of the investor’s individual profile including their return and liquidity requirements, risk tolerance, age etc…

There certainly remains a role for traditional bonds in traditional balanced portfolios although the expectations of what that allocation should deliver has to be adjusted.

We have reached the end of a four-decade bull market in bonds. In 1982, the yield on a 10-year government bond reached towards 17%. By contrast, for all the talk of rising yields over the past six months, the 10-year has only just established itself above 2% consistently in the last few weeks.

Fixed rate bonds don’t have the ability to deliver capital appreciation in the same manner they have over the last 40 years. Similarly, the crunching down of yields has reduced the perceived attractiveness of bonds as source of income – especially at the cost of eyewatering equity returns over recent years. What remains however are the defensive properties of fixed income assets. Allocation to fixed income and credit offers defensive benefits in the form of:

- Diversification

- Lower volatility and capital stability

- Liquidity

- Regular income

With expectations of an accelerated tightening schedule, rising geopolitical concerns and unresolved economic and supply chain disruptions, the outlook for equities looks strained. In such a context, we believe that credit and fixed income should be the bedrock of an investor’s defensive portfolio.

Please define floating and fixed-rate bonds. How have these performed historically in inflationary and rising rate environments?

Fixed or floating rate refers to the coupon paid to bondholders. The coupon paid on a fixed rate bond remains the same throughout the life of the bond and is expressed as a percentage. The coupon on a floating rate bond fluctuates with movements in an underlying benchmark rate – generally, the Bank Bill Swap Rate. Floating rate coupons are expressed as premium (in basis point terms) above the reference rate.

The value of these bonds behaves differently as the cost of financing changes. As the cost of financing rises, the yield offered on new fixed bonds increases and therefore the opportunity cost of bonds already in circulation reduces their value. The yield on floating rate bonds however adjusts in line with financing costs as the coupon paid is simply a premium over the swap rate which changes over time.

The actions that central banks take to combat inflation – including raising policy rates – increase the cost of financing and therefore negatively impact the value of existing fixed rate bonds.

The valuation of floating rate bonds are much less sensitive to central bank policy tightening as the yield on the bond adjusts to the new cost of financing. This is why floating rate bonds or portfolios with floating rate structures would be expected to perform better in inflationary periods as central banks such as the RBA tighten policy and increase interest rates.

Why are fixed rate bonds negatively impacted by rising rates? Where should investors allocate the defensive part of their portfolios instead?

Fixed rate bonds have an inverse relationship to interest rates. The policy rates set by central banks represent the benchmark used by a multitude of investment and debt securities.

When the cost of borrowing money rises, bond prices usually fall, and vice-versa. Investors will prefer the yield offered on newer bonds issued at the new, more attractive yield which will lead to decline in the price of bonds already in circulation.

We believe floating rate corporate debt offers defensive characteristics of traditional fixed rate government bonds but offers a higher yield and less susceptibility to changes in interest rates. Debt issued by businesses can offer a significant yield premium to government debt to account for the increased risk of default.

Corporate bonds are, however, less risky than equities as valuations are less volatile and in the event of financial distress, bondholders have higher priority of repayment than shareholders.

Alternatively for a fixed rate exposure, a shorter strategic duration target between 2 and 2.5 years is a sweet spot if the objective is a positive return (compared to a typical bond index duration which is more than double that at over 5.5 years).

Can you please provide an example of an opportunity that you find particularly attractive at the moment?

We’ve been avoiding major bank senior paper, other than for tactical reasons where we have high conviction on new issue concessions. Supporting this view, the fair value on the 5-year part of the major bank curve has leaked wider from low 60s at the beginning of the year to +92 (+30) recently, following CBA’s USD 5yr deal at +105 (swapped back on BBSW). Macquarie Bank also got a 3-year deal away in the USD market at roughly +137 (swapped back on BBSW), double the major bank 3-year spread at +67.

In comparison, the relative value on the major bank RMBS sector has moderately improved. After trading flat to the major bank 5-year, Macquarie Securitisation’s funding-only PUMA 2022-1 RMBS print at +104 saw the major bank RMBS trading +10 back from majors in line with the historic relativity. This has also repriced the non-conforming RMBS sector with the AAA senior FV at +130 from the last print in February at +105 (+25).

Though the major bank Tier 2 levels started to look optically attractive, offering 2.1x the major bank spread, we remain cautious due to potential supply and cheaper levels offshore. These T2 instruments currently trade in the offshore markets with +25 concession versus AUD counterparts.

Away from financials and securitised sectors, after a sharp sell-off over the past few weeks, there’s been renewed active interest in the long end of the ‘BBB’ rated non-financial corporates and infrastructure names. The spreads remain wide despite the marked improvement in liquidity conditions.

With a lot of mandates put on hold due to recent market volatility, another flurry of supply is likely to send the curve steeper. We continue to favour the belly of the BBB corporate curve, which has remained resilient, less susceptible to market moves.

Lastly, we are currently carrying an elevated level of cash to take advantage of any stressed offers past holding period limits as majors get close to their half year end.

What do you ask yourself before investing in fixed income and credit opportunities? How can readers use this to become better investors themselves?

A crucial element of credit investing – especially in the sub investment grade space – is issuer selection. If we assume we will hold a bond to maturity, then it is essential that we have confidence in the company to meet it obligations throughout the life of the bond. When assessing corporate issuers, we look for:

- A good balance sheet.

- Predictable cash flows.

- Hold a competitive market position.

- Have a quality, capable management and governance structure.

- Have low susceptibility to the potential impact of regulatory changes, political risk, litigation risk and other types of event risk.

The fixed income and credit market is vast and there is huge amount of due diligence, analysis and experience required in issuer selection. Direct access to corporate credit as well as the financial disclosure required to adequate asses an issuer is limited for retail investors. Publicly listed vehicles such as credit focused LITs offer an opportunity for your readers to access this market which can be impenetrable for retail investors.

What implications would persistent higher inflation have on the credit market? And how would a reversal to a deflationary environment impact credit markets?

The impact of persistent high inflation on floating rate credit would be felt through central bank policy tightening. While – as discussed earlier – changes in interest rates would not be expected to significantly impact the valuation of floating rate bonds, the yield on those bonds would increase.

Persistent inflation could have a substantial impact on costs, margins and therefore profitability and credit quality of issuers.

A defensible market position and quality management can substantially mitigate the impact of inflation on credit quality. The ability of a company to pass costs on to consumers is essential for navigating an inflationary environment.

A deflationary environment would likely see upward pressure on credit spreads due to valuation concerns. With policy rates already at or near zero globally, the ability of central banks to ease is greatly compromised and there is no monetary ammunition left to expend.

One expected corollary of a deflationary environment would be the potential degradation of credit quality. In such an environment, disciplined issuer selection becomes even more important to manage credit risk.

If you had to describe the next 12 months for fixed income markets in just three words, what would they be?

- Volatile

- Challenging

- Great opportunities

Make sense of the fixed income landscape

Fixed income in a portfolio can provide liquidity, regular income and diversify away from equity risk. Essentially, fixed income assets should provide some certainty and predictability, which can be the defensive anchor of a portfolio. You can learn more about the strategies Michael and the team manage here

4 topics

1 stock mentioned

1 contributor mentioned