The Hidden Power of Inflection Points

My investing was never the same again after I discovered this. The hidden power of fundamental inflection points radically improved my investing results.

Some lingo

But first, let’s get clear on what we mean by a fundamental inflection point. The Investopedia definition will suit us fine:

An inflection point is an event that results in a significant change in the progress of a company, industry, sector, economy or geopolitical situation and can be considered a turning point after which a dramatic change, with either positive or negative results, is expected to result.

To be super clear, we are talking about changes in the fundamental cash flows of the business, not ‘charting’ share price changes.

There are many types of fundamental inflection points. Here are just a few of the types I like to look out for:

- Turnarounds (with a major catalyst sparking the revival)

- A new fast growing product/segment, ideally whose early growth has been hidden by a larger flat or declining segment

- A major demand-side break-through such as a new distribution agreement

- Growth company tipping in to profitability (with strong operating leverage)

- Hypergrowth company that has just ‘crossed the chasm’ (a topic for another update)

- Corporate spin-offs

All of these have one thing in common, which is a very rapid acceleration in the rate of improvement in fundamental performance.

Today I’ll talk through just the corporate turnaround example, as it is where I first got started as a value investor.

Turnarounds

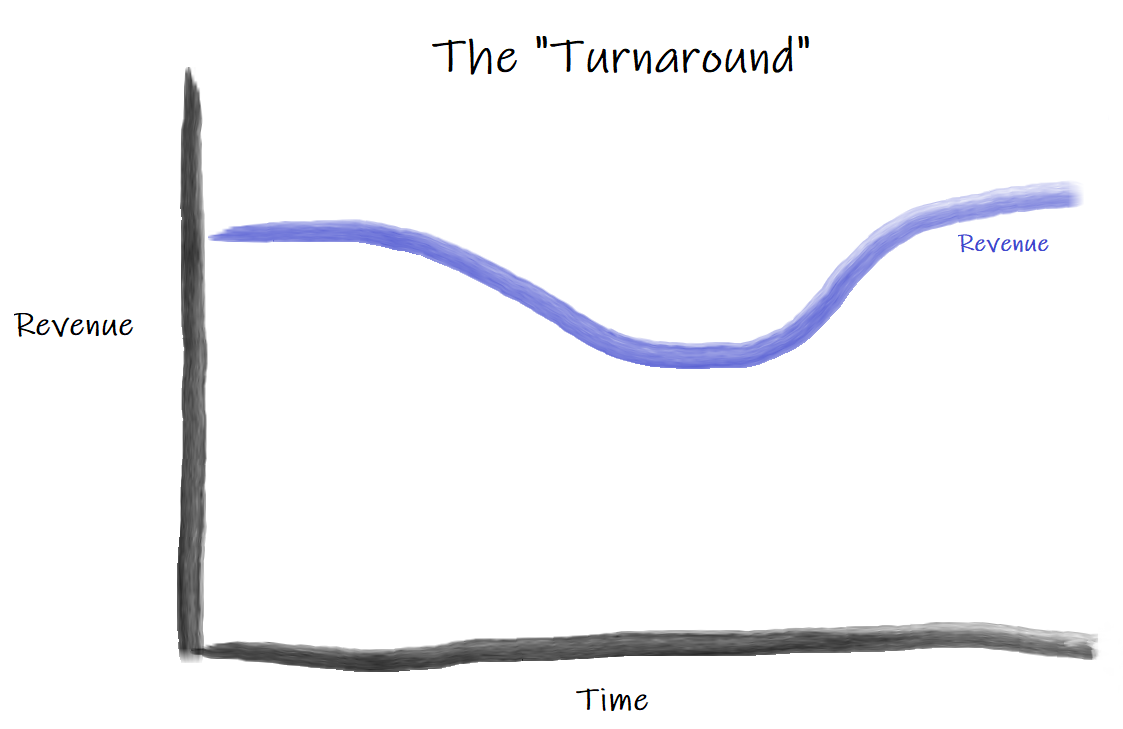

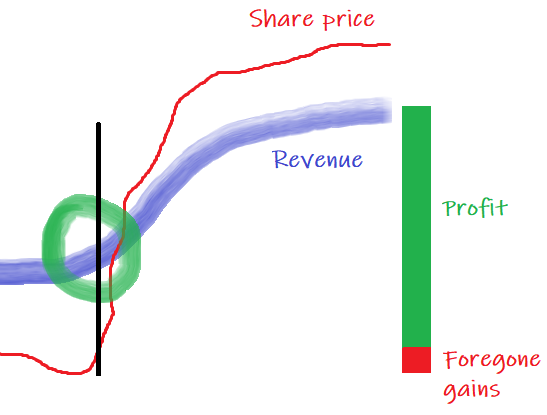

Imagine a company that has been generating steady revenue and profit when it suffers a setback and its performance takes a dive:

There can be a thousand causes. It could have been: a failed product launch; a botched acquisition; or a newly assertive competitor. Revenues slump, and profits plummet.

But whatever the cause, in this example, the declining business finally gets its act together and makes a rapid recovery. Note that this only occurs when there is a specific cause of the slump that can be quickly rectified.

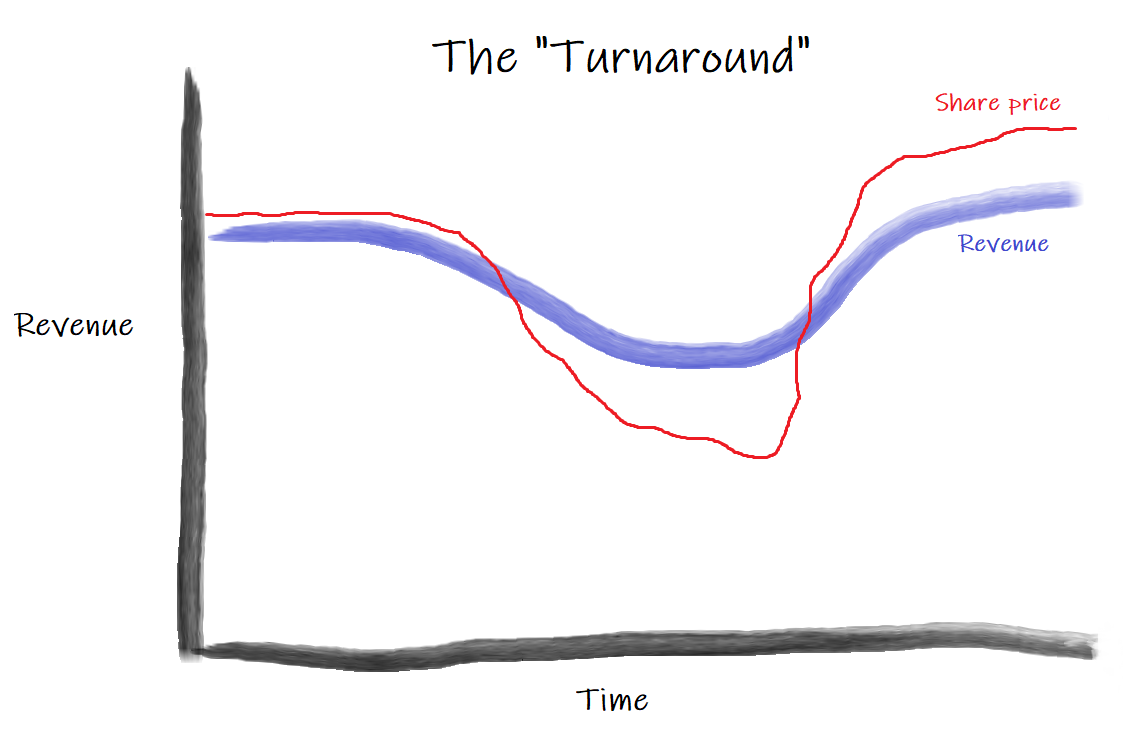

The share price response to both the slump and the recovery is normally exaggerated. Here’s the typical share price moves we’d see in this situation:

This simple chart sums up a lot of ‘classic’ value investing.

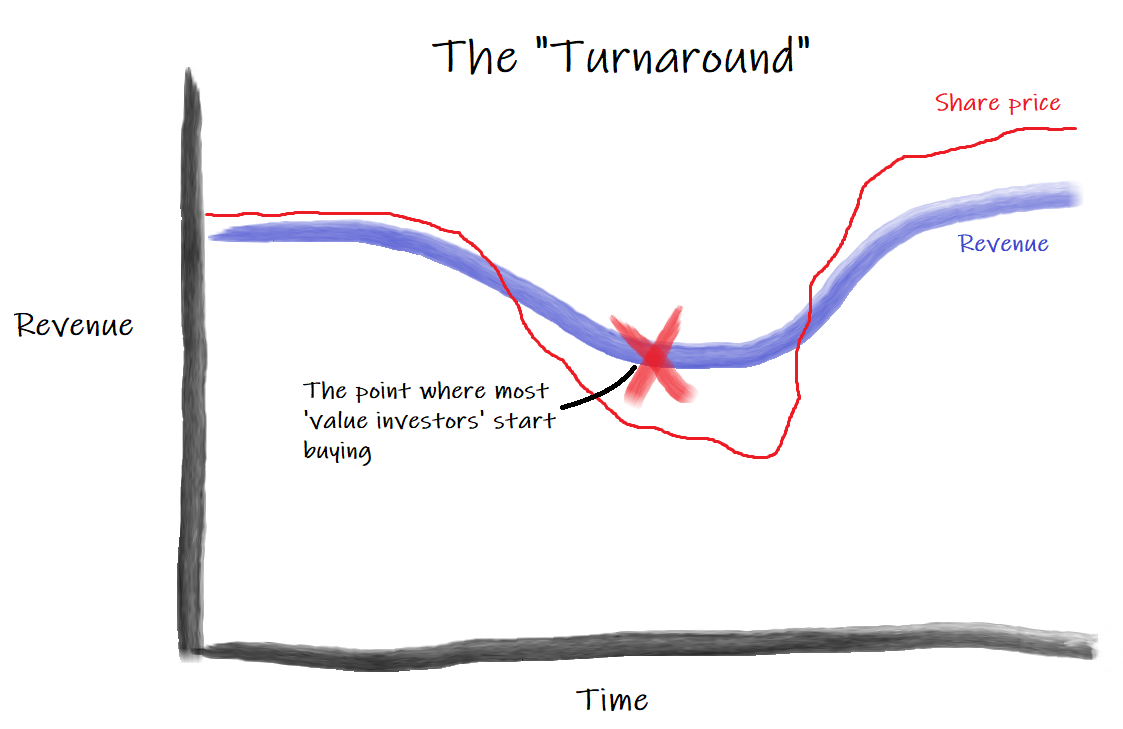

Value investors look for businesses that have had some fundamental setbacks (the dip in revenue and profit). But more importantly, they are looking for situations where the market has over-reacted to the bad news (the share price plunge) and the shares are undervalued. They purchase shares during the troughs of the market’s despair and hope to sell later, when the market’s mood has improved.

For many years this was my investing modus operandi: buy something cheap, usually watch it continue to get cheaper, finally (hopefully) a rebound arrives, sell.

It can be painful. Value investors are cursed with being early. That means suffering through significant further price falls before the company’s performance improves. Classic value investing doesn’t really have an answer to this painful process, aside from developing the stomach to hold your nerve (always good advice).

And that is actually the best-case scenario.

“Turnarounds seldom turn” — Warren Buffett

In plenty of cases the turnaround never comes. The traditional value investor is left holding the bag on to a company that looks cheap, but where performance continues to decline. The ‘cheap’ often just keeps getting ‘cheaper’. This slow-motion train wreck is known in the industry as a value trap.

But what if we could cut out most of the pain of suffering through falling prices, and almost all of the value trap blow-ups?

A better approach

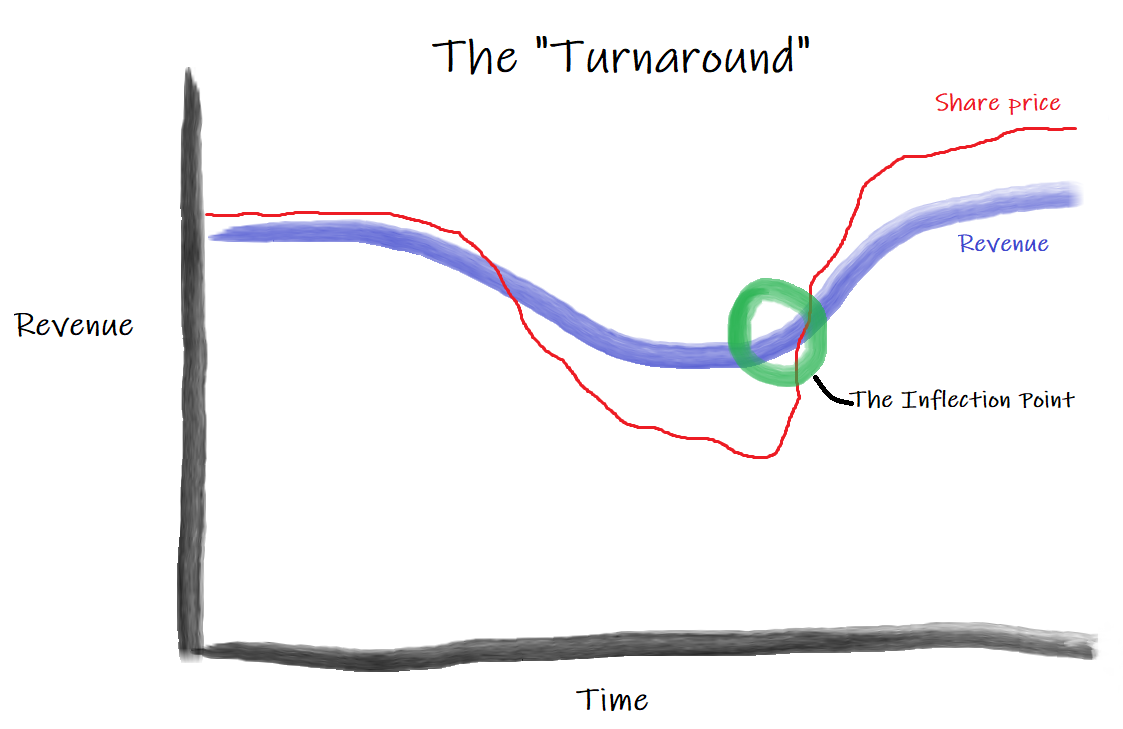

Instead of purchasing purely based on an estimated discount to intrinsic value, we can also wait for indications that a fundamental improvement is already well underway. We can wait for the fundamental inflection point:

By waiting until the inflection point has already started we avoid the worst of the losses that long-term holders have suffered. In turn we also miss out on some of the gains, since we are unlikely to be buying at the absolute bottom. But that also means we join in just when the fun is really getting started.

Most value investors arrive for the party two hours early and make awkward chit-chat with the hosts over a bowl of dip. We arrive a half-hour late, a couple of other guests have already arrived and the conversation is flowing. Soon the party will be in full-swing. Later on, when Mr Market has gotten drunk and starts making a scene, we’ll make a polite exit.

Here is a zoomed-in version:

My preferred spot is to wait until *after* there is already some compelling evidence that the company has hit an inflection point (the black line). This has the added benefit that we rely more on observation of the world as it currently is, than solely on forecasts of how it could be in future.

When executed well, this focus on inflection points can radically enhance our expected returns:

- Reduce the number of severe ‘value trap’ blow ups. This helps us win big, lose small.

- Reduce behavioural biases: less pain from holding falling shares means less temptation to sell at the worst possible time.

- Shorten the average holding period. This is a key part of generating high annualised returns i.e. it is better to make 50% in six months than to wait two years.

- Higher ‘hit-rate’ which allows greater concentration i.e. the number of profitable trades as a percentage of all trades increases.

So why isn’t everybody already doing it?

Why it works (a.k.a. why it’s hard)

Thankfully, there are several challenges to successful inflection point investing.

First: anchoring. “I’ve missed it” are three of the most dangerous words in investing.

By the time the inflection point is already underway, the share price has likely rebounded off its lows. Investors that have been watching the stock often anchor to the lows, instead of reassessing the current value. They avoid buying, thinking that they have missed the gains.

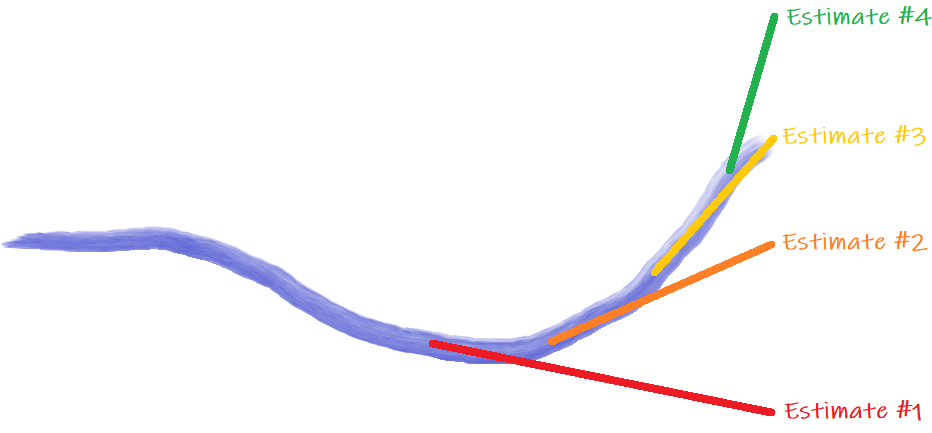

Second: cognitive biases. The changes that happen at inflection points tend to be extremely rapid. We humans are not great at exponential thinking.

Our brains evolved to be very good at linear forecasting. That lion is running towards me. I predict that if this continues I will be his lunch. I better do something. That is very helpful linear forecasting. But it is less helpful in the modern world of finance.

When it comes to forecasting rapid change, our brains are slow to adapt. The market tends to forecast based on a linear extrapolation of recent results:

The market repeatedly under-estimates how quickly the company will improve. Then finally, the market actually overshoots to the upside. The stock then becomes overvalued. Smart investors sell, and the whole glorious cycle of expectations can start again.

Third: the search is hard work. No one rings a bell to tell you an inflection point is underway.

Small-cap and micro-cap companies are often a good place to look for these opportunities. Often nobody else is watching closely. Or more precisely, nobody else that is managing enough funds to move the price. In these ‘under-followed’ cases it is often possible to identify the inflection point simply by following the company’s latest financial reports.

But it is not always that easy. Often by the time the inflection point is readily apparent in the published financials, it is already too late. Smart investors need to be doing the hard work of equity research to identify a fundamental inflection point before it is obvious in the reported results. That means digging through every piece of information about the company, it’s competitors, suppliers, customers etc. Investors also need to ensure they aren’t being fooled with a false positive. Or as Buffett calls it, a ‘turnaround that keeps on turning’. It can be an incredibly rewarding process, but it’s hard work.

Fourth: patience. Or rather, being extremely selective. It is hard enough to find a company that is undervalued. Inflection point investing means holding off, and only investing when you have found undervaluation and a positive fundamental inflection point.

Thankfully none of that is easy, or everybody would be doing it, and the magic would disappear.

Conclusion

Understanding the power of inflection points can significantly enhance a ‘classic’ value investing approach.

We’ve only scratched the surface of inflection point investing. We talked through just one example, the corporate turnaround. But there are dozens of others. In fact, we didn’t get a chance to talk about my favourite type of inflection point (a hyper-growth company that has just ‘crossed the chasm’). That will have to be the topic of another update!