The inequality of low interest rates

As global interest rates continue their march towards the floor, we continue to see asset prices inflate. But interest rates do not treat all humans equally. The benefits of compounding asset values accrue largely to the few who are already wealthy. In a lower-for-longer interest rate environment, this dynamic will only accelerate.

As global interest rates continue their march towards the floor, we continue to see asset prices inflate. Naturally, when one’s earnings on a risk-free investment diminish, one’s willingness-to-pay for higher yielding assets increases, hence, higher asset prices follow.

And we may well be in this low rate environment for the foreseeable future. Just this week, Australia’s RBA Governor, Philip Lowe, told the Australia-Canada Economic Leadership Forum that: “It's quite likely we're going to be in this world of low interest rates for years, perhaps decades, because it's driven by structural factors in the global economy.” We would agree.

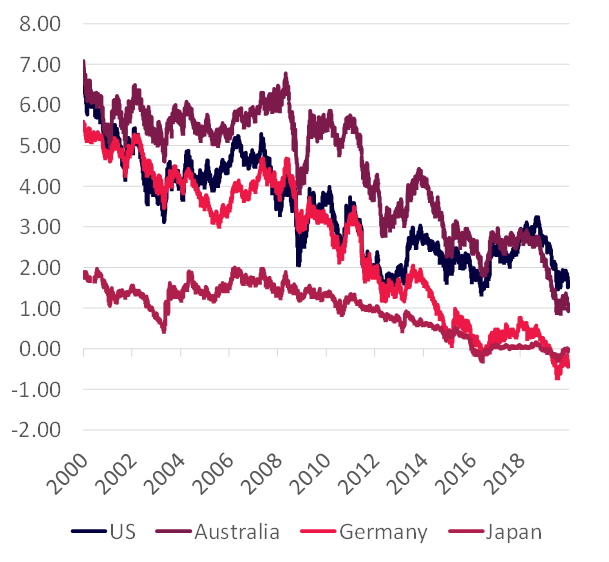

Government bond yields, 10YR maturity

Source: Bloomberg

At Montaka Global Investments, we spent a considerable portion of 2019 considering and analysing the key drivers of long-term interest rates. We summarised our findings in a whitepaper titled: Low Rates, Assets Inflate. In short, we concluded that there are compelling reasons to believe that we could be in a lower global interest rate environment for much, much longer than most believed prior to 2018. And if this is true, then asset prices – and equity prices in particular – are potentially a lot less overvalued than conventional wisdom would have us all believe.

Here is how we concluded our whitepaper on the subject:

The idea that interest rates do not treat all human beings equally is one worth exploring. A logical starting point is to consider differences in net worth and the resulting effect of interest rates, therefore. For those fortunate enough to have significant excess net worth that is not required for living, this capital can be invested in assets that will naturally compound – and even accelerate in value in a falling interest rate environment.

At the other end of the wealth-spectrum, consider those who do not have any excess net worth at all. Asset inflation does not benefit these people in any way. And, indeed, asset inflation can even hurt this cohort, to the extent living costs (such as the cost of housing) are driven up, directly or indirectly.

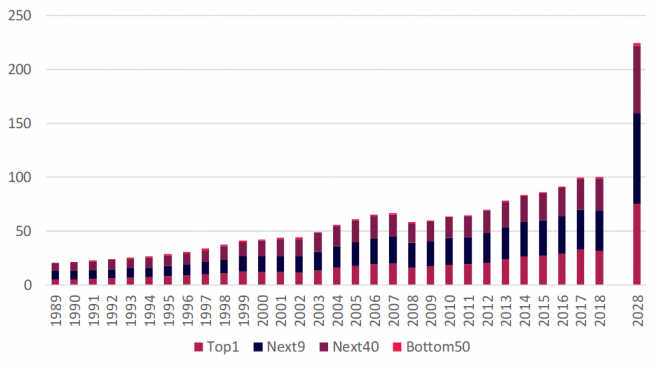

The above dynamics result in a picture that looks like the one in the chart below. The bars illustrate the level of household wealth in the US over time. Within each bar, the share of wealth relating to the top one percent is shown, the next nine percent, the next 40 percent and the bottom 50 percent (which is so small it is difficult to make out visually on the chart).

The key takeaway is this: the top 10 percent of US households have captured more than 70 percent of the gains in household wealth over time. And, therefore, the ratio of the top 10 percent to the bottom 50 percent has increased from 16x three decades ago to more than 50x today.

Distribution of Household Wealth in the U.S. (US$ Trillions)

Source: Federal Reserve; MGI estimate for 2028

We made a rough estimate what this chart might look like in 2028 by compounding this wealth at: (i) the average historical rate of increase for each cohort; as well as (ii) an estimate of the percentage uplift in asset valuations that should logically stem from an environment in which interest rates (or interest rate expectations) fell by two percent and remained at those levels indefinitely.

The point is that, if the disparity looked uneven 30 years ago, it is going to look extremely uneven in the future, in all likelihood. For example, under the scenario described above, the ratio of the top 10 percent to the bottom 50 percent would be up to 70x in 2028.

In late 2017, President Trump signed into law significant tax cuts including, perhaps most significantly, a reduction in the US corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%. In the stroke of a pen, this increased the expected future after-tax profits of every business domiciled in the US. Said another way, this created a significant uplift in equity valuations.

Following the signing, it has been reported that President Trump attended a holiday dinner at Mar-a-Lago at which he told his friends: “You all just got a lot richer.” President Trump was telling the truth. According to a recent Goldman Sachs report, the top 10 percent of US households own around 90 percent of all US equities held by households.

It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that we are hearing more noise of a potential wealth tax in the US. And concepts around Universal Basic Income (UBI) are slowly creeping into the mainstream for consideration. It is for one simple reason: the benefits of compounding asset values accrue largely to the few who are already wealthy. In a lower-for-longer interest rate environment, this dynamic will only accelerate. It is only natural for those being left behind to observe the inequality of low interest rates and grow increasingly restless.

As we concluded in our recent whitepaper on the subject: “We believe that the challenge of low interest rates could well be the defining challenge for the next generation of global leaders.”

(SMH) Low rates for years: RBA warns of risks if household debt climbs, February 2020

(FT) How America’s 1% came to dominate equity ownership (February 2020)

Andrew Macken is the Chief Investment Officer of Montaka Global Investments.

5 topics

1 stock mentioned