The inflation spike, earnings constraints and shareholders' reward-for-risk

Introduction

On August 10th The Economist magazine wrote that “shares now look more expensive—and thus lower-yielding—when compared with bonds than they have in decades.” Earlier, The Wall Street Journal ran with the heading, “The Benefit of Owning Stocks Over Bonds Keeps Shrinking: Some worry the rally is unsustainable after a gauge of stocks’ relative value falls to two-decade low.” And the Financial Review suggested that share prices offer a comparatively low return for their risk, justified only by an economic outcome of modest growth, normalisation of inflation and few adverse global shocks. None of the authors of these pieces were actually peddling a doom and gloom scenario for stocks. Rather, they were pointing out that a convergence of prospective equity and bond market returns could be a signal of downside risk to stocks.

The authors were referring to a decline in the earnings premium. The Economist, specifically, was referring to the gap between the 12 month forward earnings yield and the 10-year Treasury yield on United Stated (U.S.)-listed stocks, which had fallen to about 1 per cent. The earnings yield is the flipside of the price-earnings ratio. If investors are paying 12.5 times earnings for a stock, the earnings yield is 8 per cent. The last time the differential between short-term yields on stocks and long-term yields on government bond was as low as it is now was just prior to the global financial crisis. So, it is worth considering the relative yields on stocks, corporate bonds and government bonds in Australia, and what this means for asset allocation.

Equity risk premium

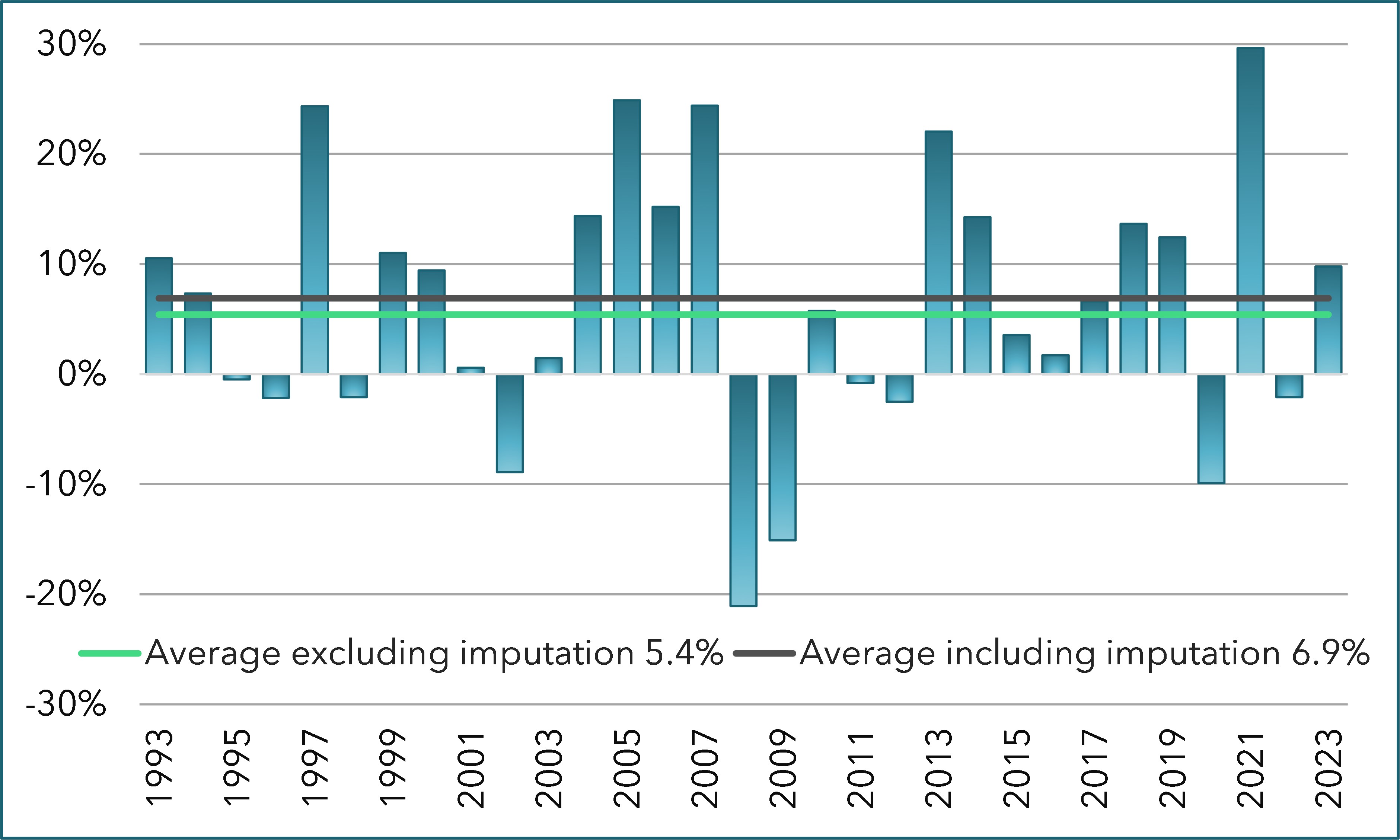

The equity risk premium represents the difference in prospective returns on shares versus a risk-free return, typically proxied by the yield to maturity on government bonds. Over the last 31 years, annual returns on the S&P/ASX 300 index have, on average, exceeded forward-looking 10-year government bond yields by 5.4 per cent (Figure 1). This figure climbs to 6.9 per cent once the tax benefits of dividend imputation are included.[i] The historical returns premium forms a baseline for the prospective equity risk premium. It represents a reasonable expectation, in the absence of timely market signals, for investors considering their allocation to shares versus bonds and other asset classes. 10-year corporate bonds with a BBB credit rating have, on average, offered a yield premium of 2.5 per cent over government bonds in the last 18 years.

However, at any point in time, the equity risk premium will fluctuate from its baseline. Equity investors change their view on the amount of risk exposure in the market, and how much compensation for bearing risk should be priced into shares. However, we cannot directly observe the equity risk premium. We can only make inferences based upon indirect information. One data point is the short-term earnings premium. On this metric, the implied equity risk premium is relatively low.

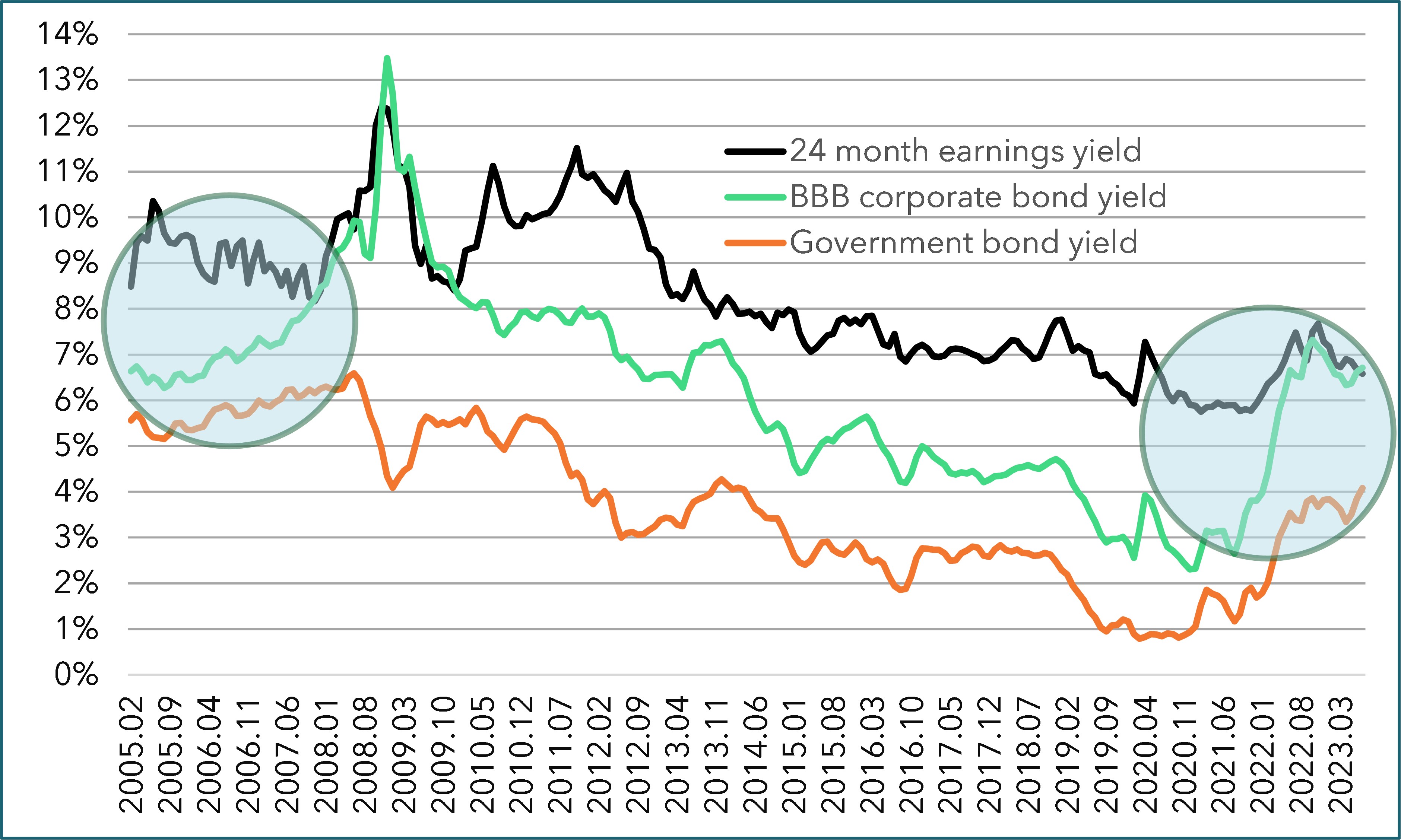

In Figure 2 I show the 24-month earnings yield for ASX-listed stocks, and the yields on 10-year BBB-rated corporate bonds and government bonds. On average, from February 2005 to July 2023, the difference between the 24-month earnings yield and the 10-year government bond yield was 4.6 per cent. In July 2023 the difference was just 2.5 per cent, following a persistent decline from 4.7 per cent in August 2021. So, in August 2021 the 24-month earnings premium was normal and in the subsequent two years has shrunk to close to its all-time low. The implication is that if the short-term earnings premium is relatively low, the long-term equity risk premium is also likely to be relatively low, and that share prices could fall substantially in order for the equity risk premium to converge to a normal level.

The only period in the time series when the 24-month earnings premium was lower was from May 2007 to December 2007, when an average of 2.3 per cent was recorded. This period overlaps with the start of one of the worst return periods for the Australian share market. From 1 November 2007 to 6 March 2009, the S&P/ASX 300 recorded a return of minus 51 per cent. This is the reason some commentators are concerned about the earnings premium today. We have a prior period in which the earnings yield and 10-year government bond yields narrowed to around 2-3 per cent and share prices fell sharply. Also note that this is the only other time period in the sample in which the earnings yield and the BBB-rated corporate bond yield converged.

However, this is the point where investors need to take a deep breath and look beyond a single event before altering their asset allocation. We need to ask why the earnings premium is low today and was low just before the global financial crisis.

First, note that yields on government and corporate bonds rose as soon as we observed a substantial rise in inflation. In August 2021, yields on 10-year government bonds and BBB-rated corporate bonds were 1.2 per cent and 2.7 per cent, respectively. In September 2021, quarterly trimmed mean inflation climbed from 0.4 per cent to 0.8 per cent and continued to increase for four consecutive quarters, reaching a peak of 1.9 per cent. In annual terms, inflation went from about 2 per cent to 8 per cent in a single year. Bond yields rose accordingly. Corporate bond yields peaked at 7.3 per cent in October 2022 and government bond yields peaked at 4.1 per cent in July 2023. In contrast, earning yields experienced just a moderate increase, from 5.8 per cent in September 2021 to 7.7 per cent in November 2022.

So, we had an inflation shock and bond prices fell, in anticipation of the reversal of ultra-loose monetary policy that was a feature of recent years. Returns on government bonds were minus 20 per cent from August 2021 to September 2022 as the yield rose from 1.1 per cent to 4.0 per cent. The cash rate target of the RBA did not even begin to increase from its low of 0.1 per cent until the May 2022 monetary policy decision. By this time government bond yields were already 3.3 per cent and corporate bond yields were 6.2 per cent.

Fast forward to July 2023 and, since August 2021, the S&P/ASX 300 has earned a return of 5.8 per cent while government bonds have lost 18.5 per cent. In short, the inflation shock of August 2021 was the catalyst for bond yields to return to normal. But short-term earnings yields have risen only marginally. Why? The share market looks beyond earnings projections one and two years out. While a shrinking 24-month earnings premium is directionally indicative of a decline in the equity risk premium, it is not a one-for-one relationship. Increases in the cash rate target are clearly having an impact on spending, and therefore are likely to impact two-year corporate earnings. Quarterly trimmed mean inflation was back to 0.9 per cent in June 2023, household consumer spending on discretionary items in the year to June 2023 was down 0.7 per cent in real terms, and analysts have cut their 24-month earnings forecasts by 13 per cent from November 2022 to July 2023.

In sum, the 24-month equity yield is low (6.6 per cent) and the 24-month price-earnings ratio is high (15) because short-term profit expectations have been curtailed. But share prices reflect a return to normal profitability.

What happened in 2007? There was one similarity: Inflation was above target. Quarterly trimmed mean inflation from June 2007 to September 2008 ranged from 0.9 per cent to 1.2 per cent. But changes in analyst earnings expectations were in an entirely different direction. From October 2005 to September 2007 analysts revised upwards their 24-month earnings expectations by 40 per cent. Recall that in the last eight months analyst earnings expectations have declined by 13 per cent. Investors in the S&P/ASX 300 had doubled their wealth in just three years and even the substantial increases in earnings expectations amongst analysts had struggled to keep up. Which means that, in 2007, the earnings premium shrunk because of optimism in the share market that was fueled by an unreasonably rosy view of the global economy. Once the U.S. property bubble burst, yields on risky assets spiked, yields on safe assets plummeted, and eventually the earnings premium reverted to normal.

The key point is that fluctuations in the earnings premium alone do not signal that share prices are unreasonably high or low. The decline in the earnings premium in 2007 was associated with very high share price appreciation in prior years, at a rate which even outstripped high increases in earnings expectations. In 2023 the earnings premium has again narrowed, but this time as a result of an inflation shock that was immediately factored into bond yields in anticipation of cash rate increases.

Bubble characteristics

Timing of entry and exit from different asset classes is one of the most challenging aspects of portfolio management. That is why portfolio managers differentiate between their long-term strategic allocation (the allocation across asset classes that aligns an investor’s risk preference with overall portfolio risk) and their tactical allocation (a deviation from the long-term strategic allocation on the basis of signals that one asset class offers relatively better value at a point in time). Most tactical decisions are an educated guess based upon conflicting signals. While tactical allocation can yield substantial gains for a portfolio, economic shocks make execution particularly challenging.

There is a difference between signals that one asset class might be relatively cheap or expensive and evidence of an asset class bubble. Notable bubbles of recent decades are the technology initial public offering (IPO) bubble in U.S. of 1999-2000 and the U.S. property bubble of 2006. Bubbles exhibit three common characteristics.

- A substantial increase in trading volume;

- A shift in the composition of trade volume from institutional to retail; and

- Transaction prices being justified without regard to fundamental indicators of value, like earnings and cash flow.

The third point on fundamentals requires elaboration. There is a difference between disagreement amongst investors about what fundamental information is most important, and how to convert that information into a fair price, versus trading without regard to fundamentals at all. For instance, investors can disagree over whether a stock should be priced at 10 or 20 times short-term earnings on the basis of the company’s long-term earnings outlook. But they agree that earnings matter. In a bubble, a higher proportion of investors trade on the presumption that asset prices will rise regardless of any consideration of fundamentals.

There does not seem to be evidence that the equity market is in a bubble. The earnings premium is low, and that is one indicator of a below-average equity risk premium. But we have not seen the three characteristics listed above in recent months. There has been some evidence of heightened optimism amongst investors in U.S. IPOs in recent years. One feature of the 1999-2000 technology IPO bubble was an increase in the proportion of newly listed companies that were not yet profitable. In recent years, the proportion of loss-making companies amongst IPOs was high, averaging 78 per cent from 2016 to 2022. We observed the same proportion of loss-making companies in IPOs from 1999-2000. However, there is a stark difference in the number of IPOs: There were 856 U.S. IPOs over two years in 1999-2000, almost the same as the 860 IPOs in the seven years from 2016-2022.

Conclusion

The short-term earnings premium has fallen to levels not seen since just before the global financial crisis. Also, for the first time since the crisis, BBB-rated corporate bond yields approximate short-term earnings yields. Investors should be wary of using the convergence of yields on stocks and bonds as a signal of equity market overvaluation. Whether stocks are cheap or expensive is beyond the scope of this note, but there are substantial differences between events of 2007 and 2023. Sixteen years ago, sharemarket investors doubled their wealth in just three prior years. Despite equity analysts increasing their 24-month earnings expectations by 40 per cent over two years, those earnings could not keep pace with share price increases. Earnings yields fell while bond yields rose.

In the last two years, bond yields increased because of an inflation shock, running well ahead of increases in the RBA’s cash rate target. The RBA’s efforts to curb spending are working, as shown in moderation to inflation, decreases in discretionary spending and cuts to analysts’ 24-month earnings forecasts. The earnings premium has narrowed because short-term earnings are under pressure at a time when bond yields are rising. Both factors are driven by inflation and the associated RBA response of increases in the cash rate target. A reduction in the earnings premium is directionally consistent with a decline in the long-term equity risk premium, but it is not a one-for-one relationship. A reduction in the earnings premium is also not one of three key characteristics of a bubble: An increase in the volume of trade, an increase in the proportion of trade volume from retail investors, and transaction prices being justified without any reference to fundamentals.

A disclaimer is in order. While I comment on historical and prospective returns on equity and bond markets, nothing in this note should be taken as a prediction of future returns. The purpose of the note is to point out that the short-term earnings premium (a comparison of short-term earnings expectations relative to share prices minus the 10-year government bond yield) is directionally indicative of a decline in the long-term equity risk premium (the incremental return shareholders receive for bearing equity risk). But the earnings premium is not a signal that necessarily predicts near-term equity market movements. The earnings premium has declined in recent months to the level last seen just before the global financial crisis, after which Australian-listed shares lost about half their value. What preceded the global financial crisis – a property bubble, and a great deal of equity market optimism – was the catalyst for a share market correction. The equity premium is not in itself the signal for a share market correction.

References

Endnotes

[i] The averages are computed by first averaging annual returns for 12 definitions of a year (ending January, February, March etc.) and then averaging the 12 annual averages. For example, the average annual equity premium for years ending June was 6.2 per cent, and the average annual equity premium for years ending January was 7.6 per cent. No definition of a year is any more informative than another, so I compute an average across all 12 year definitions.

5 topics