The little known, $317bn to $430bn QE4 wave that will swamp QE3...

Folks are starting to turn their minds to what life looks like after the end of the RBA's bond purchase program (aka quantitative easing or QE). There's a fairly robust consensus that Martin Place will look to accelerate its QE3 taper from $4 billion/week currently down to $2 billion/week in February 2022. What few investors appear to understand is that there is a much larger round of long-term, quasi QE4 coming via the banking system, which we currently size at $317 billion (with a range of between $250 billion to $450 billion) starting at the end of June 2021 or $430 billion if we begin at the end of December 2021. That is more bond-buying than all the RBA's three QE programs combined (ie, $100 billion each for QE1 and QE2, with another $102 billion expected for QE3), which will have profound long-term consequences for asset pricing.

Importantly, the mix of assets banks buy is likely to be very different to what the RBA has acquired: whereas the RBA has split its purchases 80:20 between Commonwealth and State government bonds, the banking system is currently skewed 68:32 in favour of State securities because of the fact they pay a positive spread above the swap rate whereas Commonwealth government bonds don't.

While we have important wages and inflation data ahead of us before the RBA makes a final decision on the direction of its QE3 taper in February, a smooth exit via an accelerated taper down to $2 billion/week makes considerable sense. After the messy experience with the yield curve targeting policy (YCT), the RBA will be keen to ensure that financial markets are not again bullying it into hasty policy decisions, and aggressively tightening financial conditions by pricing in interest rate hikes that are miles ahead of its credible central case.

That is certainly what has happened thus far with banks being forced to sharply increase the cost of their fixed-rate borrowing products--by more than 50bps pa--as a result of the much higher cost of capital that has been imposed on them by markets. Combined with a striking spike in public commentary on the spectre of interest rate increases, tighter financial conditions are likely already impacting economic activity (and slowing housing ahead of the RBA's expectations).

Beyond the fact that the RBA's bond purchase program has been highly effective in keeping the Aussie dollar low and devoid of the problems that plagued YCT, extending QE in February will also provide a powerful device to compel markets to defer the pricing of the RBA's first interest rate hikes (ie, you can hardly price in hikes while the RBA is still tapering QE). Even after the RBA's efforts to pour cold water on interest rate expectations, the market is still pricing in a cash rate of almost 100bps by the end of 2022.

Martin Place has also made it clear that the actions of other central banks are crucial in this context, and with Aussie wages and inflation running at half the pace evidenced in the US, it is hard to imagine that the RBA would want to appear more hawkish than the Federal Reserve by exiting its own QE program way ahead of the anticipated completion of the Fed's tapering in mid-2022.

What few investors appear to understand is that there is a much bigger, $317 billion de facto QE4 wave that is coming down the pike. And the size and speed of this QE4 wave is directly impacted by the size and speed with which the RBA tapers QE3...

The QE4 program we are talking about here is the bond-buying required by the Aussie banking system to meet its regulatory liquidity targets. There is a general understanding that banks need to buy government bonds (specifically, Commonwealth and State government bonds) to replace the alternative liquid assets that they held via the circa $139 billion Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF), which APRA announced in September would be closed by the end of 2022.*

What is not widely appreciated is that the government bond-buying required by the banking system as a result of banks repaying the RBA the $188 billion they owe under the Term Funding Facility is actually much bigger than the bond-buying precipitated by the closure of the CLF.

This is best understood as follows. When the RBA buys a government bond under its QE program, it creates digital cash that it deposits in the bank accounts of the counterparties it is buying the bonds off. This digital cash is held by banks on deposit at the RBA and counts as a so-called Level 1 "high-quality liquid asset" (HQLA1) that is included in the banks' liquidity coverage ratios (LCRs).

The LCR reflects the amount of emergency liquidity banks have to hold to meet a 30-day outflow of money in the event they suffer a liquidity shock. It is simply the amount of HQLA1 banks have relative to the projected net cash outflows in this liquidity shock. In Australia, the banking system has typically maintained LCRs over 130% as a buffer above the official 100% regulatory minimum (banks ordinarily have an internal target of 125% or more). That is, banks hold HQLA1 that is worth more than 130% of their simulated 30-day cash outflows.

The only other assets that banks can hold as HQLA1 to meet their LCR targets are Commonwealth and State government bonds. So the more digital cash the RBA prints as part of QE, the more HQLA1 the banking system ends up holding in the form of deposits at the RBA.** Equally, the faster the RBA tapers QE, the less digital cash banks have, and the greater their demand for other forms of HQLA1 (ie, Commonwealth and State government bonds), all else being equal.

The same process applies when the RBA lends money to banks via the Term Funding Facility. To extend the $188 billion of TFF loans, the RBA deposited digital cash in the accounts banks have at the RBA. While the banks lend this money out to customers, the cash stays within the banking system and cannot be disappeared as such. Right now there is about $360 billion of excess cash that banks have on deposit at the RBA as a result of QE, the TFF, and also the RBA's now-disbanded YCT policy (the bonds bought to maintain YCT are still on the RBA's balance sheet).

Importantly, as banks start repaying the TFF money to the RBA, this automatically destroys the digital cash the RBA created. Similarly, as governments begin repaying the bonds the RBA bought through QE, digital cash on deposit at the RBA is likewise destroyed (unless the RBA reinvests this money into new bonds). In summary:

- The RBA buying bonds via QE creates digital cash for the banking system, increasing HQLA1 that counts towards their LCRs;

- The RBA lending money to banks via the TFF creates additional digital cash, also increasing HQLA1 and hence boosting the banks' LCRs;

- Conversely, banks repaying the TFF destroys this digital cash, decreasing both HQLA1 and the banks' LCRs; and

- As bonds mature on the RBA's balance sheet, digital cash is similarly destroyed decreasing both HQLA1 and the banks' LCRs.

Now it is well-known banks have to buy extra HQLA1 to replace the $139 billion CLF. This CLF money was included in the banks' LCRs. But by the end of 2022, it will be no longer permitted. The much more interesting question is how much HQLA1 the banks have to buy to (1) replace the CLF and (2) replace the disappearing excess cash they currently have on deposit with the RBA as the TFF is repaid over the next 2-3 years. There is also the question of whether the RBA allows the bonds it has bought via QE and YCT to mature, which would further increase the amount of HQLA1 the banking system has to purchase to replace the excess cash on deposit at the RBA that is evaporated as these bonds mature.

Estimating the total HQLA1 shortfall is quite complex, and has to account for a range of different factors, including:

- The closure of the CLF by the end of 2022;

- How quickly the bank system's balance-sheet grows: faster growth needs to be funded via debt, and these liabilities generally increase the banks' net cash outflows, reducing their LCRs, and increasing their demand for HQLA1);

- How the banks' balance-sheets are funded: different types of deposits and term debt attract different net cash outflow assumptions--for example, if retail deposits slow and this money shifts to businesses as households spend their savings, the banks will be hit with higher net cash outflow assumptions on flighty business deposits, reducing their LCRs, and boosting their demand for HQLA1; and

- Finally, how quickly banks repay the TFF money and the speed with which the RBA tapers its QE program (faster TFF repayments and a more rapid RBA taper create more HQLA1 buying demand given their is less cash on deposit at the RBA).

The good news is that our analyst team has modelled all of the above. In our central case, we find that the banks will have to buy $317 billion of HQLA1 (Commonwealth and State government bonds) over the next circa 3 years starting after 30 June 2021 (or $430 billion if we start after December 2021). That is slightly bigger than the RBA's QE1, QE2 and QE3 programs combined. One important difference with the banking system's bond buying is that it will not be split 80/20 between Commonwealth and State government bonds as the RBA does when it undertakes QE.

Banks hedge these bonds using asset swaps, and are understandably focussed on minimising the net interest margin drag between the cost of their debt funding and the returns they earn on HQLA1. Whereas they normally earn a negative spread on Commonwealth government bonds above the swap rate, State government bonds usually pay a significantly positive spread above the swap rate.

This is why banks have a strong bias in their HQLA1 portfolios towards buying State government bonds in preference to their Commonwealth equivalents: since 2015, State bonds have accounted for 63% of the banks' total Commonwealth/State government bond portfolio, which has more recently risen to 68%.

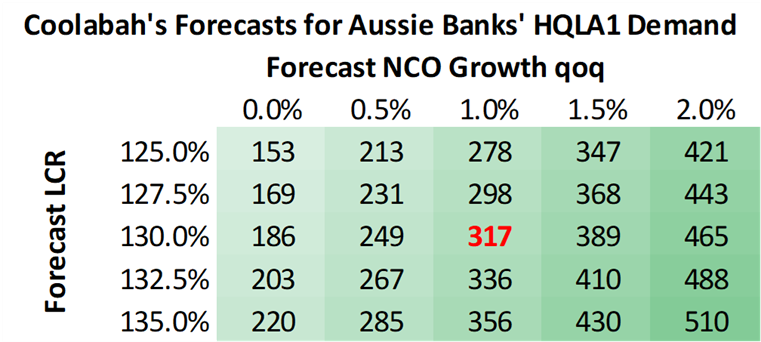

In the table below, we provide sensitivities around our central case as a function of net cash outflow growth and the banks' targeted LCR. We would expect NCOs to be positively related to balance-sheet growth, and our central case calibrates them at circa 4% annually. While the banking system as a whole has historically maintained an average LCR above 130%, we have assumed it is calibrated at 130% going forward. (Even if we drop the assumed LCR down to the banks' internal targets of 125%, HQLA1 demand is still $278 billion.)

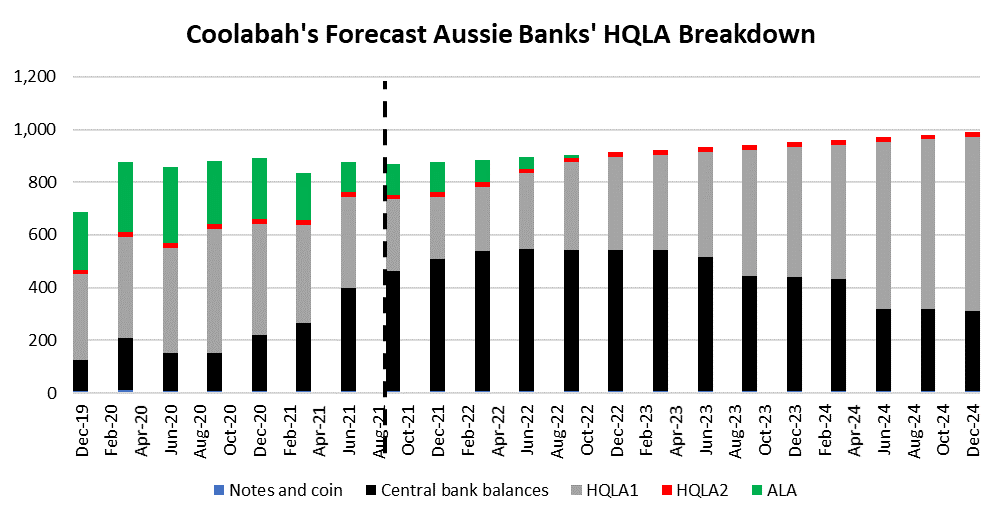

The chart below shows the change in the composition of HQLA1 over the next three years. Central bank balances refers to the excess cash held by banks on deposit at the RBA, which slowly declines over time as the TFF is repaid. If for some reason the RBA did a hard-stop of QE in February (ie, did not extend to $2 billion/week for another three months), this would materially bring forward the banking system's demand for HQLA1.

On a year-by-year basis, our central case projects the following HQLA1 buying profile from the banks with the splits based on their current portfolio mix between Commonwealth and State government bonds:

- CY2022: $121 billion ($82bn of States and $39bn of Cwealth)

- CY2023: $137 billion ($93bn of States and $44bn of Cwealth)

- CY2024: $172 billion ($117bn of States and $55bn of Cwealth)

This actually adds to $430 billion, not $317 billion, because the $317 billion figure starts at June 2021 whereas the $430 billion HQLA1 shortfall starts at December 2021 (between June and December 2021, the banks' HQLA1 demand temporarily falls as an artefact of QE2 and QE3 given the RBA is creating so much digital money).

It is critical to note that this buying is timed in our quarterly financial model so that banks always hit a 130% LCR within the quarter. Since banks know about the HQLA1 shortfalls years ahead of time, they will almost certainly get ahead of these gaps. So buying in 2022 could well be substantially larger than buying in 2023, for instance. In addition, banks might be worried about the quantity of this buying reducing the margins (spreads) on their HQLA1, which could encourage them to bring forward some buying to get ahead of the curve (and their peers). A final factor that has to be considered is that banks are holding over $360 billion of excess cash earning 0% interest at the RBA. They therefore have a strong commercial imperative to try to spend this money on higher-margin HQLA1 that pays a positive spread above the swap rate (and above the 0% interest they earn at the RBA), which minimises the drag on their net interest margins.

There are several risks to this central case, including:

- The banks' balance-sheet growth could be stronger, driving higher net cash outflows, especially if the RBA does not hike until mid to late 2023;

- The RBA could effect a hard stop to QE3 in February, bringing forward more HQLA1 buying demand into 2022;

- The composition of bank deposits could shift from retail households to wholesale businesses, which attract higher net cash outflow assumptions and would drive additional HQLA1 demand; and

- APRA could continue to tighten-up the net cash outflow assumptions that banks apply to different types of liabilities, driving higher NCOs (this has been the direction in which APRA has been heading of late).

*Recall that the CLF was originally created by APRA and the RBA as a substitute for banks holding government bonds on the basis of the belief that there was an insufficient quantum of Commonwealth and State government bonds outstanding to support the banking system's liquidity requirements. But with the RBA forecasting that there will be $1.6 trillion of these securities outstanding by the end of 2022, there is no longer a need for the CLF.

**This is technically known as excess cash held in the banks' exchange settlement (ES) accounts with the RBA, or excess ES balances.

Access Coolabah's intellectual edge

With the biggest team in investment-grade Australian fixed-income and over $8 billion in FUM, Coolabah Capital Investments publishes unique insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid leveraging its 14 analysts and 5 portfolio managers. Click the ‘CONTACT’ button below to get in touch.

3 topics