The lucky country has become the lazy country

The Reserve Bank of Australia’s embattled governor, Phil Lowe, will not want to leave his successor with an inflation crisis to contend with, the blame for which will, of course, be sheeted home to their pilloried predecessor.

It is entirely plausible, even probable, that Lowe will see it fit to lift interest rates at his final three meetings at one of the most powerful – and now panned – public institutions in the land.

This would push the cash rate to 4.85 per cent, bang on where the RBA’s internal research suggested it had to be to get core inflation back to the mid-point of the central bank’s 2 per cent to 3 per cent target band by late 2025.

But with a nascent wage-price spiral emerging, and community expectations regarding the trajectory of inflation drifting inexorably higher following an 8.6 per cent minimum wage increase (and a 5.75 per cent boost for award wages), this may not be fast or high enough.

The RBA’s research assumed the cash rate would be 4.8 per cent by May or August, and further noted that this was only 100 basis points above the neutral or normal rate that would not put any downward pressure on inflation.

Assuming 25 basis point increments, the earliest the RBA will get to 4.8 per cent will now be September. All of this supposes that there are no further nasty upside surprises to future inflation data, which would compel the RBA to raise its forecasts for both inflation and interest rates.

Australia’s cash rate has historically averaged 1.6 percentage points above its US equivalent. Yet the US Federal Reserve’s policy rate is already at 5 per cent to 5.25 per cent – and this week it said it was targeting 5.6 per cent within months.

New Zealand’s central bank is sitting at 5.5 per cent. And the British are now projected to hit 5.5 per cent to 6 per cent. Markets predict that the Canadians will soon head beyond 5 per cent.

Productivity doldrums

Martin Place faces acute policy challenges. Despite 400 basis points of hikes, the housing market has surprisingly started booming again. Consumers have saved about 20 per cent of their annual incomes during the pandemic, care of cash hand-outs and lockdowns, which they have yet to spend. If Australians follow the American example of doing so, this would pump substantial additional demand into the economy and intensify inflationary forces.

The massive consumer cash buffers explain why the economy has been so incredibly resilient in the face of record rate increases. It has also helped that most home loans written during the pandemic had their interest rates fixed at very low, circa 2 per cent levels for three to five years.

The equity and risk-on junkies have latched on to the news of our economic resilience as a source of hope that we will avoid recession and engineer the dream of a soft landing. They have been neurologically conditioned to quick fiscal and monetary policy fixes – zero rates, money printing and the politicians’ spend-a-thons – to bail us out of every problem.

But this was only possible in a low inflation world. We confront the opposite today. The resistance of economic activity – and hence inflation – to the much higher cost of capital only signals to the central bank that it needs to do more. And it portends a long, painful cycle involving a multi-year asset price adjustment process.

Most state governments continue to spend like mad men, burning more money than they are collecting, pouring more fuel on the inflationary fire. (The only rational fiscal reformer appears to be NSW Treasurer Daniel Mookhey.)

Thursday’s jobs data showed the labour market remains exceptionally strong and has yet to roll over, remarkably registering a decline in the unemployment rate to 3.6 per cent, which is close to the nadir reached in the mid-1970s.

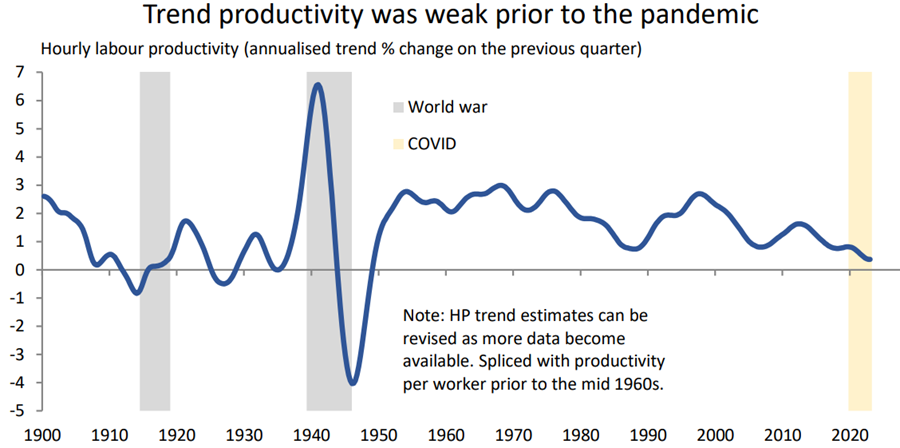

Trend labour productivity – or the output we are producing per worker – is the worst it has been since World War II. This is partly driven by massive underinvestment in technology and productive capital: on Coolabah’s numbers, Australia has recorded the weakest sustained peacetime growth in its capital stock since the 1930s depression.

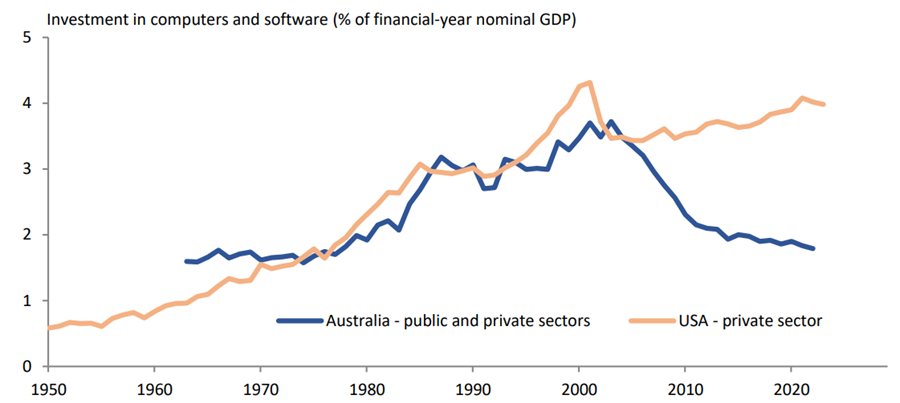

This reflects the poorest peacetime public and private sector commitment to new investment as a share of nominal GDP since the 1940s. While many of our companies are cashed-up, Aussie businesses appear focused on paying shareholders rather than buying or building new equipment and technology, creating a profound productivity and inflation problem.

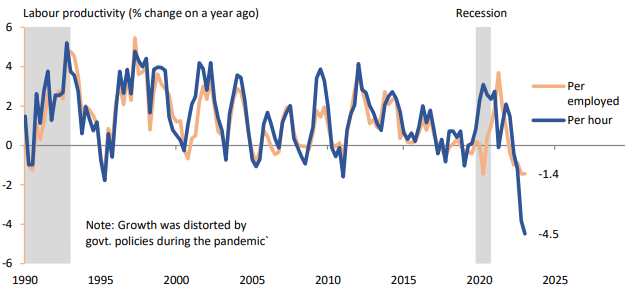

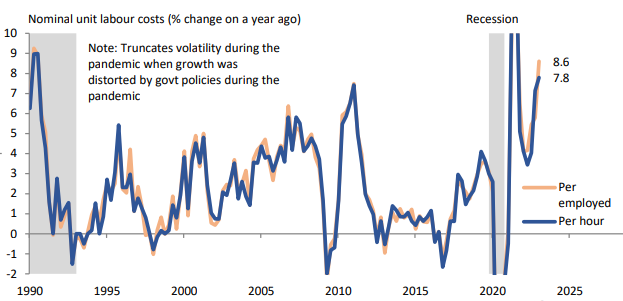

One illustration of this is the fact that Australia invests less than half of what the US private sector does in computers and software as a share of nominal GDP. This has contributed to the worst trend labour productivity in many decades, which in turn means that the marginal labour cost of businesses producing new products and services has risen at the most rapid rate since 1990 (ignoring COVID-19 distortions).

Defaults loom

While wages might only be growing at about 4 per cent annually, which is ostensibly less than headline inflation, the amount of money businesses are spending on labour to produce every new unit of output has surged to 8 per cent annually (because of horrific labour productivity). And it is this marginal labour cost of producing stuff that is the key variable fuelling our high inflation, according to the RBA’s research.

It explains why Australia’s services inflation, which is a measure of demand-side price pressures, has surged to a 7 per cent annualised pace, higher than the US. Coolabah’s chief macro strategist, Kieran Davies, recently addressed the debate around whether profits or labour costs are the main driver of Australia’s inflation crisis. His research shows that while both contribute, labour costs emphatically dominate.

As borrowing costs escalate, we should see more and more cracks appear across the economy. The sudden reduction in the price of over-inflated commercial properties in recent weeks is one canary in the coal mine. While delinquencies on bank balance sheets remain very benign, we have continued to observe a very sharp climb in the delinquencies reported by unregulated non-bank lenders on their prime and sub-prime home loan portfolios.

The major banks’ AA-rated senior-ranking bonds are now paying interest rates north of 5 per cent, which will soon exceed 6 per cent. Their BBB+ rated Tier 2 bonds offer 6.5 per cent interest rates, which will shortly rise to over 7 per cent. These are the new hurdle rates for everything.

If you want to allocate capital to real estate or equities or risky debt, one should prudently demand high-probability yields that are in the double-digit domain.

Since late 2021, we have warned of the coming recession and the worst default cycle since 1991. Expect to see a wave of defaults in the commercial and residential developer spaces in particular.

A-grade office properties are still only providing gross yields of 4.5 per cent, and that is before incentives, which can be up to 30 per cent. Once you strip out incentives, the actual “passing” yield on A-grade offices can be as low as about 3.5 per cent, which is miles below what you earn on riskless bank deposits.

For A-grade office property to be accurately revalued relative to current risk-free interest rates, many experts believe that valuations will have to adjust down by 15 per cent to 30 per cent. (Note that this logic does not necessarily apply to essential niche sectors in the property market that do trade on higher yields.)

A 20 per cent reduction in commercial property valuations could push some investors beyond their gearing targets, which may trigger more forced sales, creating a negative feedback loop.

Defaults and distressed sales: this is the way.

To find out more about Coolabah's new Floating-Rate High Yield Fund, click here. First published in the AFR here.

3 topics