The Lucky Country - 3 reasons why Australia will emerge better than most

Back in January when the bushfires were raging, I feared Australia’s luck had ran out. But right now, I thank god I live in The Lucky Country! Donald Horne’s original conception of the term in the 1964 book of the same name about Australia being run by “second rate people who share its luck” always seemed a bit too negative to me.

Sometimes it may seem that way for a patch and yes mistakes are made, but when it really matters, I reckon we are led pretty well. Particularly in times of crisis. Think the 1980s when Hawke and Keating opened up and modernised the economy. Or through the GFC when a rapid policy response was a big reason Australia avoided recession. The response to the current crisis will likely also go down as a time when Australia rose to the occasion.

Of course, we are still not out of the woods on coronavirus and there are some bad stats ahead on the economy. This is indicated by our Australian Economic Activity Tracker which is based on high-frequency alternative data and is running down 40% on year-ago levels, reflecting a preponderance of components most affected by the shutdown.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

The good news is that it is up from its early April low, but there is still bad news ahead of us in the official statistics. Unemployment likely spiked to around 10% last month which is the highest since the 20% seen during the Great Depression and official data to be released in the months ahead is likely to reflect a 10 to 15% contraction in the economy in the first half of the year, all of which risks further depressing confidence.

But three things suggest Australia looks likely to come through this period of global misery relatively well compared to many other countries and this may mean the Australian economy contracts less and rebounds faster, ultimately supporting Australian asset classes relative to other countries’ assets.

First, Australia has performed better than many countries in controlling coronavirus

While things were bleak in late March, Australia’s success in “controlling” coronavirus (touch wood) stands out globally. After a rapid escalation in new cases, Australia imposed a shutdown around 22 March. New cases peaked in late March at over 500 a day and have since declined to less than 30 a day, albeit with a few clusters still causing problems. New cases may have peaked in the US but are still averaging around 29,000 per day.

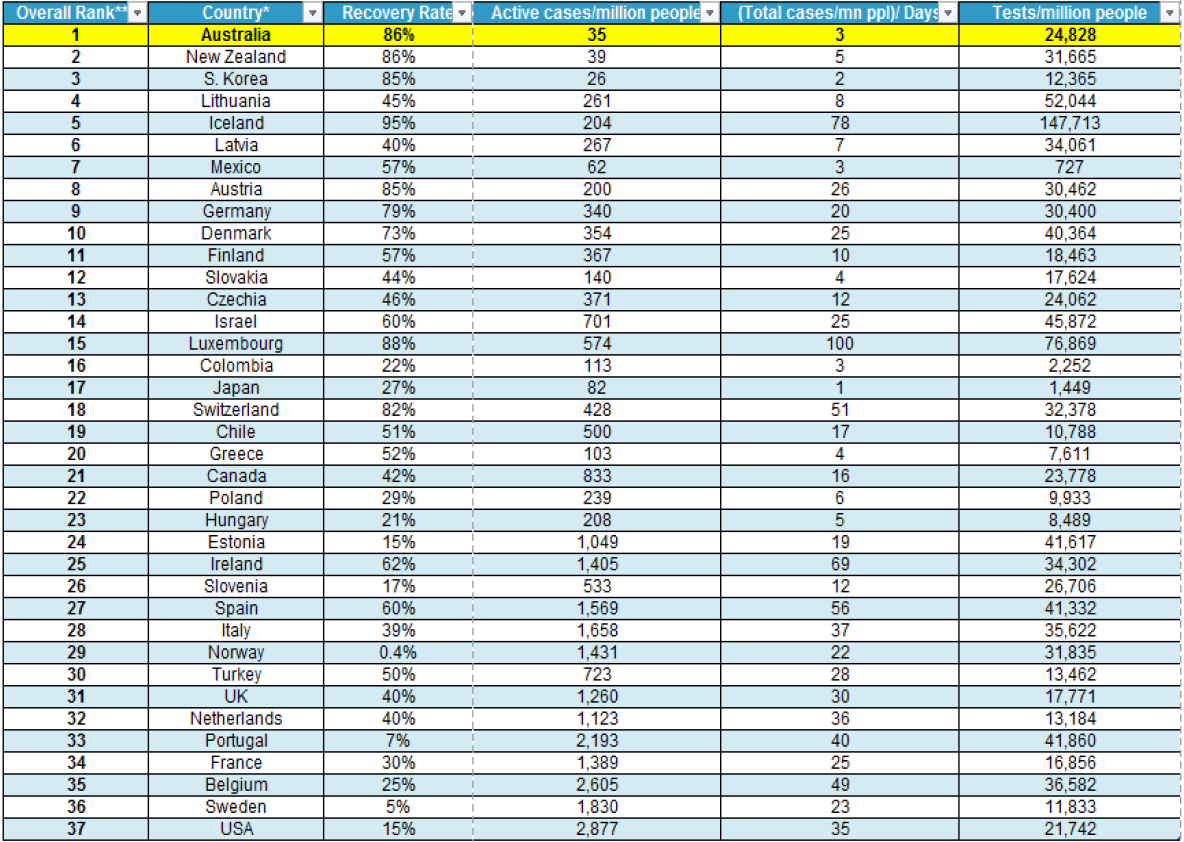

Comparing OECD countries in how they are managing the coronavirus outbreak (based on recovery rates, active cases per capita, total cases per capita adjusted for the number of days since the first case and testing per capita) Australia ranks first, with NZ 2nd (guess where your next overseas holiday might be!) compared to Italy at 28th, the UK at 31st, Sweden at 36th and the US the worst performer in the OECD at 37th.

Click to enlarge

Source: Worldometer, AMP Capital

Better weather, less congested living, a younger population and luck may have played a role, but the big driver looks to have been a public health response driven by expert medical advice as opposed to bravado or crackpot theories. And this has been backed up by Australians pulling together to do the right thing. By contrast, Europe and the US have been marked by a slower response (eg lockdowns in Italy and Spain did not occur until new cases per million people were around 30, compared to around 12 in Australia). And Australia has achieved a similar virus outcome with a less stringent lockdown to New Zealand.

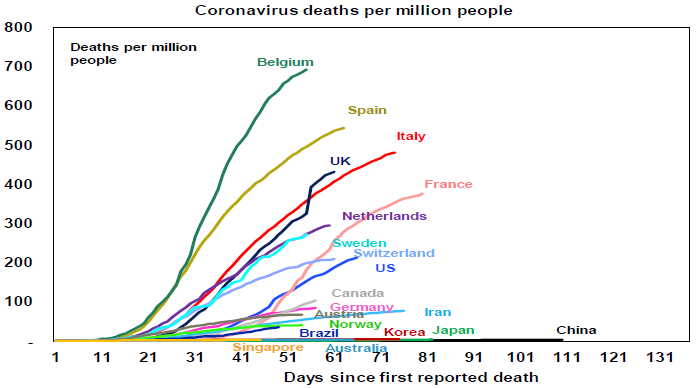

Australia’s better record in containing the virus means two things. First, it has kept pressure off the health system so those who need hospitalisation can get it. As a result, Australia has managed to do a much better job of saving its own people than many other countries. Deaths per million people are around 3.9 in Australia, compared to 84 in Germany, 221 in the US, 280 in Sweden, 443 in the UK and 485 in Italy – that’s 124 times worse than Australia’s death rate! The value of saved lives swamps the cost to the economy from the shutdown.

Source: Worldometer, AMP Capital

It also provides Australia more scope to open the economy sooner and with greater confidence that a “second wave” of cases will be avoided – in contrast to the US where there is no clear downtrend in new cases. Indications from the Government are that a phased easing of the shutdown looks on track to start this month with most businesses running again by July.

Second, Australia has seen a superior policy response

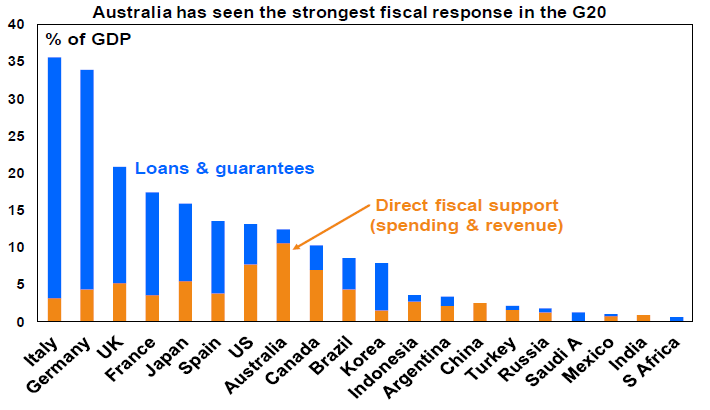

The global government policy response to the economic threat posed by coronavirus shutdowns has been huge. See the next chart. However, in many countries it includes a large element of loans and debt guarantees as opposed to actual fiscal stimulus in the form of spending or tax cuts. For example, providing a loan (or a guarantee to enable a loan) to a business to help it survive the shutdown versus providing it with a wage subsidy.

Source: IMF, AMP Capital

Loans and guarantees are helpful but they leave businesses more indebted, whereas actual fiscal stimulus provides a direct boost. So actual fiscal support is a better measure and on this front Australia at 10.6% of GDP has provided by far the strongest fiscal stimulus of G20 countries.

What’s more, Australia’s centrepiece JobKeeper wage subsidy is superior to approaches taken by many other countries as it keeps people “employed”, minimises confidence zapping negative headlines around unemployment, preserves the employer/employee relationship, keeps workers getting paid and provides a subsidy to struggling businesses. Unemployment is likely to rise to around 10% which is bad, but its far better than the 15% that would likely occur in the absence of JobKeeper or 20% or so unemployment in the US.

Third, Australia’s major trading partner is 2-3 months ahead of the rest of the world

Finally, we may benefit from our biggest export market – China, which takes a third of our exports - being ahead of the global recovery curve by around 2-3 months and focused on infrastructure spending. This explains why prices for our key export - iron ore - are holding up relatively well compared to say the price of oil (of which we are a net importer).

Implications for the Australian economy

If, as appears likely, a phased easing of the lockdown starts this month, then April should prove to be the low point in economic activity and growth should return to the economy in the second half. This does not mean that things will quickly bounce back to “normal” – the easing of the lockdown will likely be gradual to minimise the risk of a “second wave”, some businesses will not reopen, uncertainty will linger, debt levels will be higher and business models will have to adapt to different ways of doing things. This may mean returning to the office on a rotational basis and shops & restaurants reopening but with distancing rules.

Domestic travel may be back within a few months, but international travel looks unlikely in the absence of a vaccine until next year (except to NZ). But it will still see a return to growth, albeit it may not be until end next year before economic activity returns to pre-virus levels.

The combination of better success in controlling the virus with less risk of a second wave, better protection of the economy with a stronger policy response and Australia’s exposure to China make it likely that the Australian economy will contract less and recover faster than other comparable countries.

While many fret that without tourism and immigration Australia can’t recover, this is not true. The travel ban has only accounted for a small part of the hit to the economy. Australia actually has a tourism trade deficit of 1% of GDP (we lose more from Australians going overseas than we gain from foreigners coming here) so a ban on international travel will actually boost GDP.

However, we do have a 2% trade surplus in education, and this would be lost if foreign students can’t come. Similarly, immigration contributes just less than 1% to economic growth each year in Australia. However, this is all dwarfed by the 10 to 15% hit to economic activity which has mostly come from the domestic shutdown. And it could be argued that a workable testing and quarantine requirement could be introduced to allow students and immigrants to return on a 6-9 month timeframe.

Risks to watch

The main risks to watch for are: a “second wave” of coronavirus cases driving a new shutdown beyond the six-month protection out to September provided by JobKeeper, increased JobSeeker and the bank debt payment holiday; the lockdown triggering a house price crash resulting in severe second-round effects on the Australian economy – this is probably a much greater risk if the lockdown continues beyond September, and political tensions around the origin of Covid 19 damaging Australia’s trade relationship with China in some way.

Implications for investors

If, as we expect, the combination of better success in controlling the virus, a stronger economic policy response and exposure to a recovering Chinese economy result in a relatively stronger recovery for the Australian economy then Australian assets should benefit relative to global assets. This could come via an appreciation of the $A which is what has happened lately.

3 topics