The not so Grande Chinese property crisis

When America sneezes, Australia catches a cold but what happens to Australia when China chokes on a property crisis? We are about to find out! The property sector represents around a quarter to a third of the Chinese economy. Rather than rebounding after the end of its strict COVID restrictions, the Chinese economy is heading into a crisis.

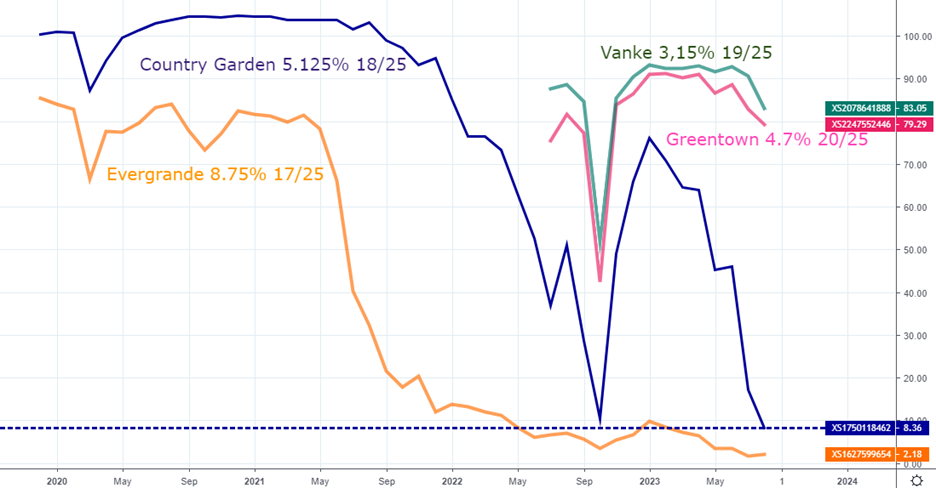

This month’s chart shows the price of four bonds over time with each bond belonging to a different giant Chinese property developer. Two of those property companies are in big trouble: Country Garden (the purple line) and Evergrande (yellow). This can be seen by their bond prices below falling far from their par value (USD 100) towards zero. The other two are faring better but as their bond prices below show, they are still being impacted by what is happening with Country Garden, Evergrande, and the Chinese property market more generally.

What went wrong?

The simple answer is that companies like Evergrande became over reliant on credit and that the Chinese government turned the credit tap off in August 2020 with its “three red lines” policy. The Chinese government wanted to reduce speculation in the property market. Instead, they have caused its crash.

As property developers with dubious finances had their credit squeezed, their construction of existing and new apartments began to slow. This sent Chinese property investors into a panic.

Many investors were speculating on property and needed ongoing price rises to make money. But when panic set in, demand fell, and prices began to fall. Many investors got stuck with properties they could not afford, and this has pushed demand and prices down further.

In a vicious cycle, this fall in demand has worsened the financial position of property developers who can no longer find enough buyers for new projects and can no longer rely on new buyers for revenue to fund existing and future projects. The Chinese property market is having a Minsky moment.

At the end of August, there were an estimated 648 million square metres of unsold homes in China.

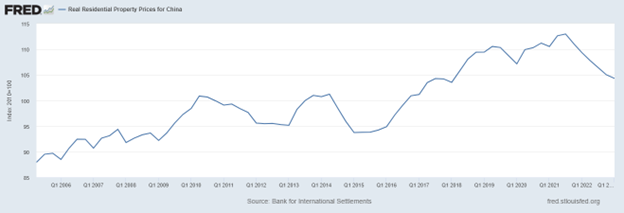

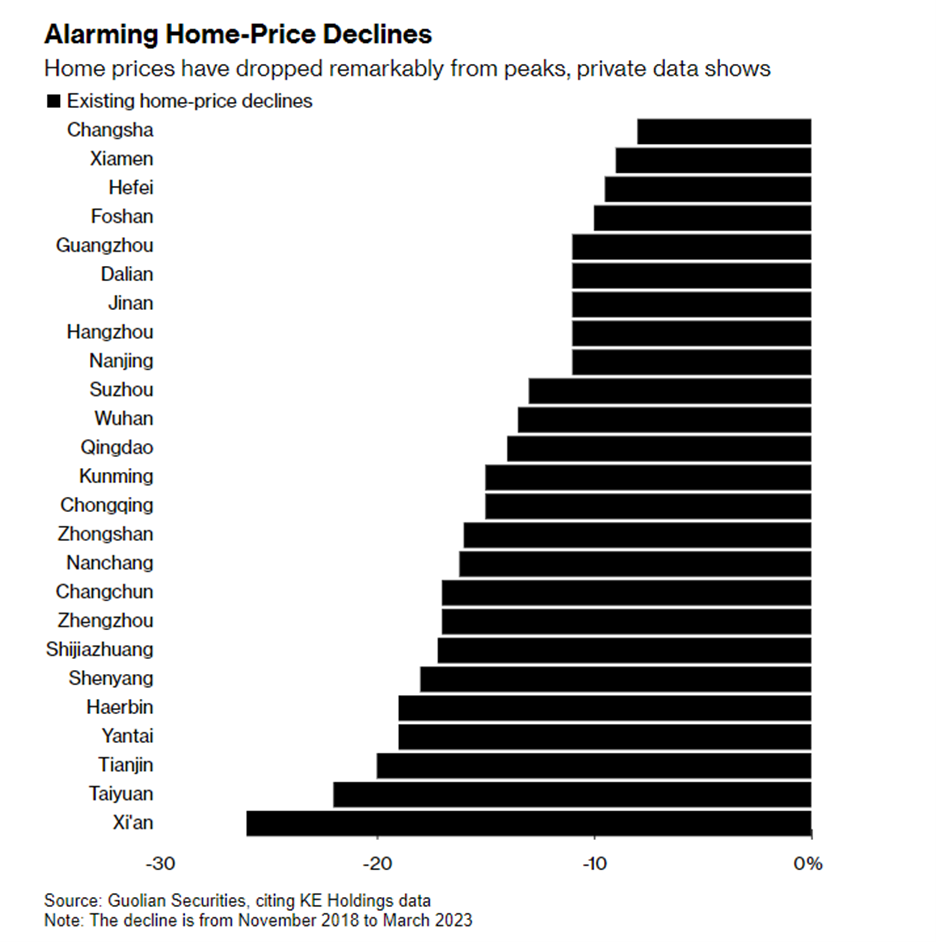

According to official Chinese statistics, house prices have only fallen around -7% compared to their recent peak in Q3 2021 (see chart below). However, independent researchers have found falls from -8% to -26% for 25 Chinese cities between November 2018 and March 2023 (see second chart below). The actual peak-to-trough decreases for these cities could be greater, but the researchers only could obtain data back to November 2018.

Evergrande

Evergrande is the poster child for the crisis. It first defaulted on debt in September 2021, which is when the yellow line in the chart-of-the-month first plunged (first chart).

In March, it announced a restructuring of its offshore debt. In August it announced that it plans to file for bankruptcy in the US.

In September, it deferred a meeting with creditors, many of whom are now looking to liquidate the company - an initial hearing will be held in Hong Kong on October 30. Its stock has been suspended (again).

“Based on the company’s current situation and consultations with its advisors and creditors, the company considers it necessary to re-assess the terms of the proposed restructuring to meet the company’s objective situation and the demand of the creditors,” Evergrande.

What does this mean for the Chinese economy?

Around 70% of Chinese household wealth is invested in the property market. So, as property values fall, the wealth of Chinese households is falling. The Chinese government (and the world) had hoped that the Chinese consumer would lead Chinese (and global) in 2023 as they exited COVID restrictions. Instead, it looks like Chinese households will be reducing their consumption. Those working for or connected to the property companies will be even more adversely affected. Then, there are the second-order effects on the rest of the economy such as the impact on indebted local governments who were reliant on property sales for much of their revenue. China could face a severe recession. It may also find itself in a similar position to Japan after its property bubble burst in 1992: decades of low growth and deflation.

What does this mean for the Australian economy?

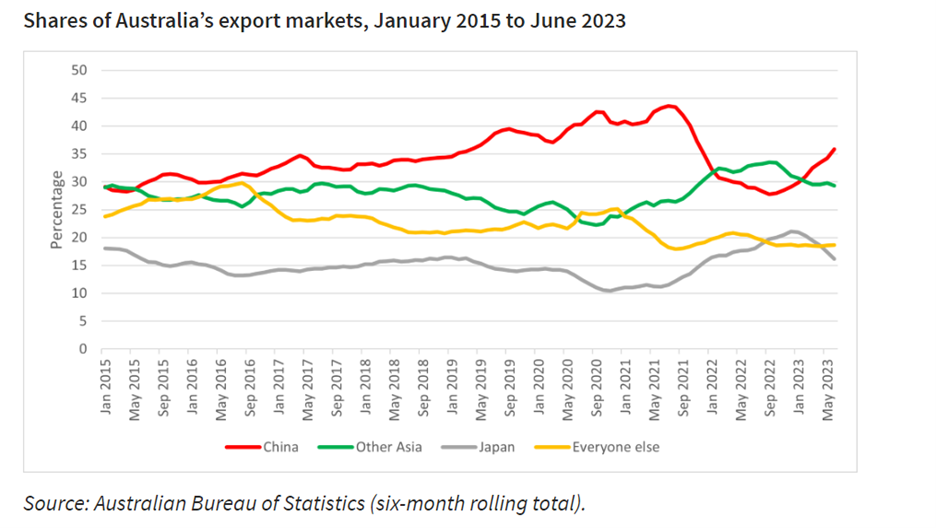

After the recent thawing in trade relations, China is again Australia’s top trading partner with 36% of total exports by value in the first half of 2023 (see chart below).

Our biggest exports to China are iron ore, lithium, and LNG. Iron ore is used by China to make steel with the property sector a key customer. Expect iron ore exports to be affected. Lithium is used to make electric batteries with the Chinese electric car market a key customer. Chinese electric car sales have rebounded so far this year, but this cannot last.

So, if the Chinese economy falls into crisis, it will drag upon the Australian economy. This will be in addition to our own slowing domestic economy and the slowdown in America and Europe. Unlike the GFC, there are no Chinese exports to save us this time.

If the impact of the Chinese crisis on our growth is severe it may put the RBA in a sticky situation, if inflation is still high. Could we have stagflation?

What does this mean for Private Debt in Australia?

The impact on private debt will depend on the impact of the Chinese crisis on the Australian economy. The good news is that the Australian economy has so far proved resilient.

Private debt providers would feel confident to help their clients through a mild recession but a bigger crisis would pose a greater challenge for everyone.

5 topics