The power of the CEO

In most areas of human endeavour, the value of better performance increases linearly within a narrow range as one goes from average to exceptional. In a few disciplines, however, value can increase exponentially and by an extraordinary magnitude, usually where individual performance can be leveraged across a vast market or large organisation. As Bill Gates famously noted:

“A great lathe operator commands several times the wages of an average lathe operator, but a great writer of software code is worth 10,000 times the price of an average software writer.”

Other pursuits where this dynamic exists include media, professional sports, and, indeed, investing.

In our experience, however, there are few areas where this phenomenon is more pronounced than with corporate CEOs.

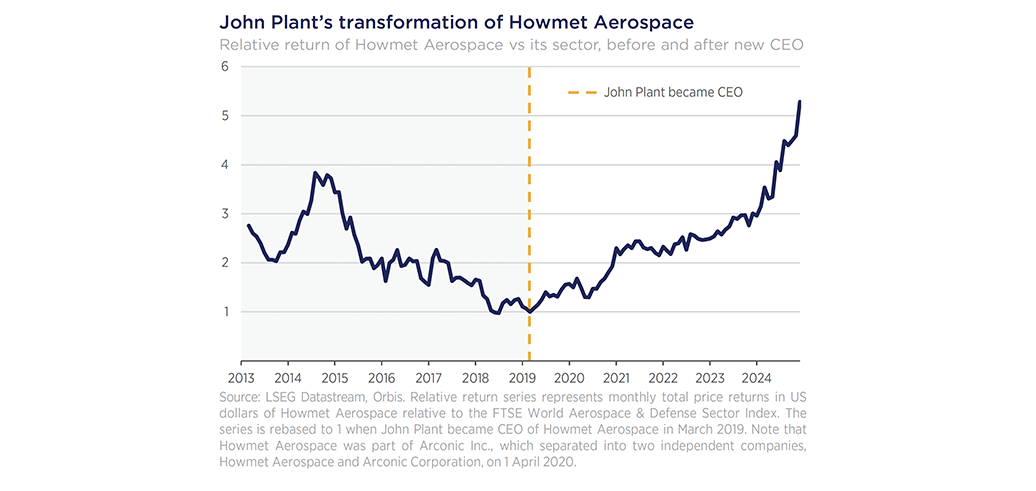

The difference in long-term shareholder value creation between an average or even top quartile CEO and a top 1% CEO can defy the imagination. Few examples provide a more vivid illustration than Howmet Aerospace, which we owned in the Orbis Global Equity Strategy almost continuously from 2013 until this most recent quarter.

We first invested in Alcoa, as Howmet was then known, with a belief that the business was substantially undervalued. While most investors were focused on its legacy aluminium operations, we believed the real crown jewel—its mission-critical aerospace parts business—was both underappreciated and underperforming its potential. Unfortunately, for the first five years of our investment, the market’s pessimistic view prevailed. The company languished and badly underperformed the market, suffering from lack of price and cost discipline, terrible capital allocation, poor investor communication, corporate governance challenges, and a revolving door of CEOs. Finally, in early 2019, following a failed attempt to sell the company, Howmet installed John Plant, the recently named board chair, as CEO.

John came to Howmet following a distinguished tenure running the auto supplier TRW. Upon taking the helm at Howmet, John moved with breakneck speed, spinning off and selling non-core businesses, instilling commercial discipline across the organisation to ensure the company was fairly compensated for the value it delivered to customers, simplifying the organisational structure and eliminating layers of management, removing structural costs, driving operational focus, and reinvesting in those areas where the company was most competitively advantaged.

Now, nearly six years later, the results have been extraordinary.

Howmet shares have outperformed their aerospace peers and the US market by a wide margin—and John’s transformation of the company will rightly go down in the annals of corporate history as one of the greatest industrial turnarounds of the last several decades.

What is most notable about this example, however, and why it is such a striking illustration of the power of a top 1% CEO, is that John achieved these results during a period of unprecedented challenges in the commercial aerospace market and with the same assets as his predecessors—he simply was much more effective.

To be sure, CEO talent is a necessary ingredient for such extraordinary achievement, but it is usually not sufficient. CEOs also need the right motivation. Ideally, the largest dose of such motivation is intrinsic—the person simply loves to play the game and is inspired by the challenge—but financial incentives matter a lot, and often more than we want to admit. As Charlie Munger observed, “I think I’ve been in the top 5% of my age cohort all my life in understanding the power of incentives, and all my life I’ve underestimated it. And never a year passes but I get some surprise that pushes my limit a little farther.”

Unfortunately, and although well-intentioned, most corporate boards fail to put in place incentives that animate the intensity and entrepreneurial spirit needed to drive extraordinary shareholder outcomes.

With little skin in the game and heavily influenced by proxy advisors and passive investors who are indifferent to the relative performance of companies, too many corporate boards appear to be primarily focused on minimising their own career risk rather than maximising returns for shareholders.

This usually means sticking closely to consultant-defined “best practice” and ensuring that CEO payouts don’t deviate too far from the norm, especially to the upside.

This has important consequences.

First, although the typical executive compensation scheme is intended to align CEO interests with those of shareholders and to “penalise” underperformance, the reality is that we often see narrow differences between the rewards for average and extraordinary performance. Facing a situation with limited upside opportunity, the rational strategy for value-maximising CEOs is to focus on avoiding risks that could cause them to lose their jobs and their multi-million-dollar annuity payments. This is hardly a recipe for greatness.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, such schemes are unlikely to attract top 1% CEOs in the first place.

Great CEOs, like great investors, are hungry to eat their own cooking and will seek opportunities that allow them to participate meaningfully in the value they create.

At Howmet, John opted to receive only a modest salary with no traditional incentive compensation in exchange for a large grant of restricted stock that would only vest if Howmet achieved ambitious stock price targets over the long-term. Knowing John, we are doubtful he would have taken on the role for a more traditional incentive package.

Today, John’s ownership stake in Howmet is worth approximately $400 million. For shareholders, this should be a cause for celebration—indeed, we have been delighted with the difference Howmet’s performance has made for our clients. But it is exactly the sort of outcome that many corporate boards seek to avoid because of the ire it can draw from proxy advisors and passive investors who are often more focused on the absolute dollar value of management compensation than value-for-money.

Ultimately, this speaks to a deeper truth that is at the root of the issues outlined above. By their nature, most public companies suffer from a significant and difficult to resolve principal-agent problem between shareholders and the executives hired to run the company, which is exacerbated by the lack of alignment from the boards who are entrusted to manage the problem in the first place.

Our preference, therefore, is to avoid the problem altogether by investing alongside principals like John.

Our experience has been that a top 1% talent with a meaningful ownership interest in the business is an extraordinarily powerful force for long-term shareholder value creation.

Of course, these opportunities are rare—and even less likely to be undiscovered by other investors—so we have to make the most of them when they come along. Fortunately, the vast US market provides a fertile hunting ground, and we are pleased that a substantial portion of the Orbis Global Equity Strategy’s US holdings today fall into this bucket.

Last quarter, we wrote in detail about Brad Jacobs and our investment in QXO. In our view, Brad is the quintessential top 1% owner-entrepreneur, and our investments in his companies today (QXO, RXO, GXO, and XPO) represent about 15% of the portfolio. Other US companies that we believe fall into this category include Interactive Brokers (Thomas Peterffy and Milan Galik; 4% of the Strategy), Motorola Solutions (Greg Brown; 1% of the Strategy), and Corpay (Ron Clarke; 6% of the Strategy). Collectively, these stocks represent more than a quarter of the portfolio today and about half of the Strategy’s US exposure.

Of these positions, Corpay is worth revisiting. We last discussed the company in our September 2022 commentary when it was known as Fleetcor, and it has since become the Strategy’s second-largest holding. Chairman and CEO Ron Clarke, who built the company over the last 20+ years, owns about 5% of the shares, and we have high conviction that he is very much a top 1% CEO.

Put simply, Corpay helps other companies manage their expenses and pay their vendors. The company today operates three major lines of business: Vehicle Payments, which facilitates payment for fuel, tolls, and parking, Corporate Payments, which enables accounts payable automation and cross border payments, and Lodging Payments, which helps businesses manage travel accommodation for customers and employees.

While these lines of business may appear disconnected on the surface, the critical common foundation for each business is a powerful two-sided network of merchants and business customers that creates a significant competitive moat and enables Corpay to offer compelling value to customers while also earning attractive economics.

These attractive unit economics are another important similarity across Corpay’s different businesses. In financial terms, Corpay spends about 50 cents in sales and marketing to acquire a dollar of recurring revenue that sticks around for 10 to 12 years and drops through to operating income with around 60-70% incremental margin. This basic formula has been remarkably consistent over the long term, even as the underlying mix of revenue has evolved away from the company’s roots in fuel cards.

With great visibility into these attractive and consistent unit economics, Ron seeks to manage the company to produce a steady growth algorithm of approximately 10% revenue growth and low teens EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation) growth. Moreover, very high returns on organic reinvestment have allowed Corpay to grow at an attractive rate while simultaneously generating substantial free cash flow, which Ron has astutely reinvested into high-return acquisitions, further enhancing value for shareholders.

Long-term results under Ron’s leadership have been stunning, with 10%+ revenue growth, 50%+ EBITDA margins, 30% returns on equity, and 20% earnings per share growth.

These metrics put Corpay in a rarified group—only a small handful of well-loved, celebrated businesses like Microsoft, Nvidia, and Visa have achieved similar results over the last decade.

Despite these impressive attributes and track record of shareholder value creation, Corpay shares have lagged in recent years due to a confluence of short-term headwinds and investor fears about potential disruption in the company’s fuel card business. Since 2021, shares have derated from about 22x forward earnings to about 15x, while the S&P 500’s multiple has risen to 28x forward earnings. Meanwhile, the likes of Microsoft, Nvidia, and Visa currently trade at 31x, 31x, and 27x forward earnings, respectively.

We believe this creates an unusually attractive opportunity. Indeed, not only do we expect recent headwinds to abate, but we see potential for revenue growth to accelerate above 10% over the next three to five years. For example, we believe Corporate Payments has a durable growth rate of 15-20%, and will soon represent more than 35% of revenue, compared to about 20% of revenue in 2019. At the same time Corpay’s Fleet business—which has grown more slowly—will fall to just over 30% of revenue compared to nearly half in 2019.

It’s not often that we can find a business with Corpay’s superior fundamentals trading at a meaningful discount to the US market. It is even more unusual to find one that is also run by a top 1% owner-CEO like Ron Clarke.

Compare this to the situation that passive investors face today when allocating capital to the US market, where a small handful of widely appreciated winners have driven performance and pushed the market’s valuation to an elevated level.

While it’s possible that the momentum continues, we believe the risk-reward proposition is unappealing. We are fortunate that we can play a very different game and invest instead in a much smaller set of companies where the opportunity is underappreciated and the odds appear stacked in our favour.

2 topics