The price of doing more fiscal policy

I was recently asked whether it is really true that the AA and AAA rated state governments are having to pay materially more to raise capital to fund their budget deficits than Australia's banks, which all have lower credit ratings---and in many cases substantially lower ratings in the higher risk BBB band (eg, Bank of Queensland, Bendigo, and ME Bank).

There is of course also the argument that the states are part of the federation and explicitly backed by it through revenue streams like the GST, whereas banks are less explicitly government guaranteed (they have a limited government guarantee of their deposits and various implicit guarantees).

This disconnect has been canvassed repeatedly in recent weeks by analysts, economists, and economics commentators, such as the AFR's highly regarded Canberra-based economics and politics correspondent John Kehoe in this story.

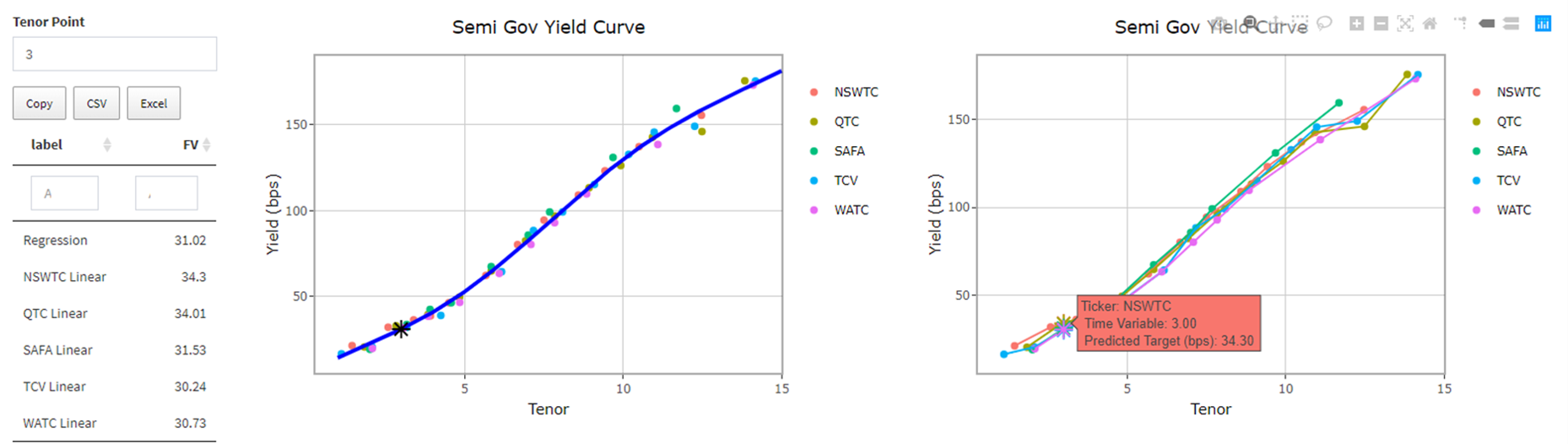

So let's examine the data. The three screenshots below highlight the price the various state governments pay to raise money at different maturities ranging from one year to more than 10 years. For three year money, states like NSW are indeed paying as much as 0.34% pa (see the table on the left-hand-side of the first image immediately below), which is materially above the price of three year money for banks, which is just 0.25% pa. The banks are currently accessing up to circa $200 billion of this funding via the RBA's novel Term Funding Facility (TFF). (Click on the image to see the data more clearly.)

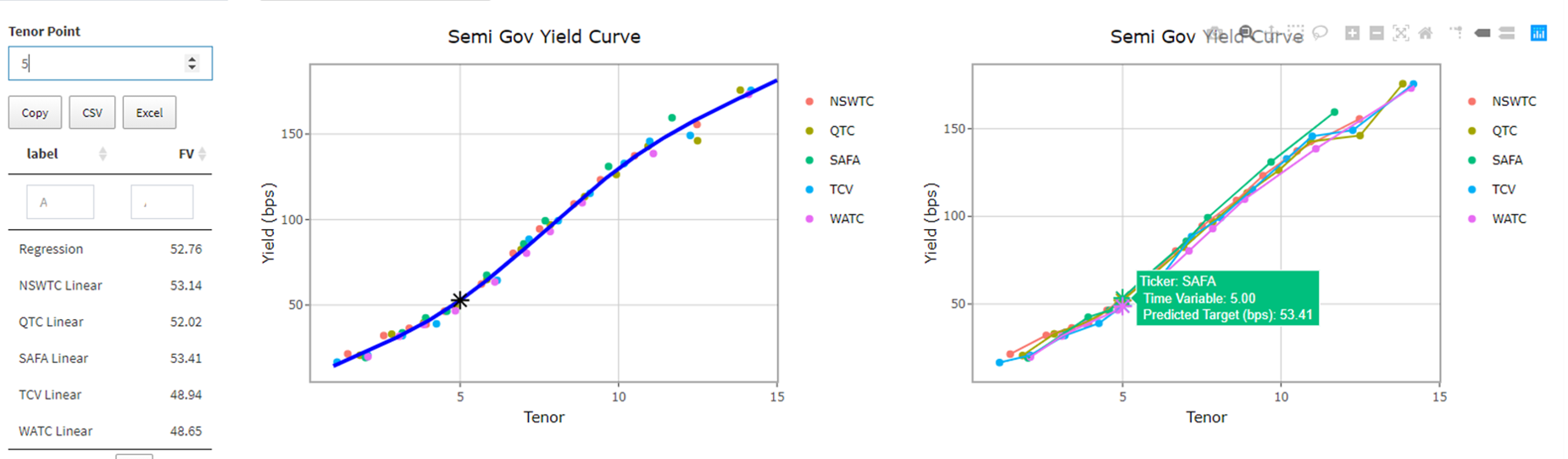

In practice, state governments prefer longer-term funding of between 3 years and 15 years to match the capital investments required to build and fund long-dated infrastructure projects, amongst other things. And the longer the tenor, the more they have to pay for it.

So when we look at the price of five year money (next image), it jumps to more than 0.53% pa for NSW (again see the table on the left hand side), which incidentally is especially odd because NSW right now has the most expensive cost of capital of all the major state governments out to about 10 years (ie, it pays more to raise money than QLD, Victoria, and WA). This is historically very unusual---as the biggest state with the strongest AAA credit rating, NSW has historically paid amongst the lowest prices to access capital---and particularly bizarre given S&P has put Victoria on watch for a 50% probability of a downgrade from AAA to AA+. (Click on the image to see a better version.)

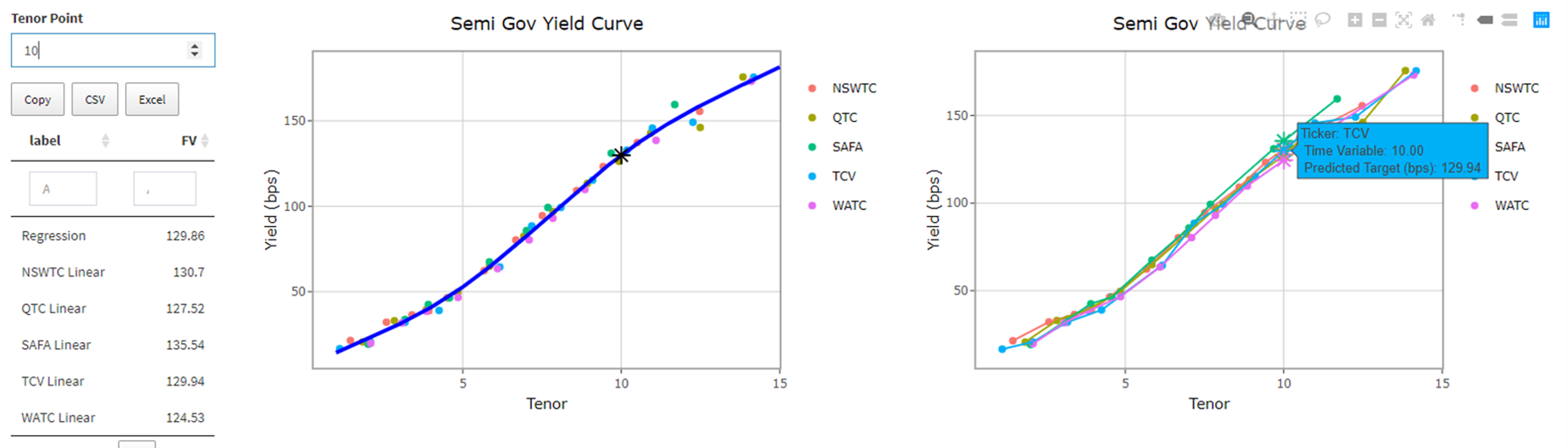

Since the states have been focussing on long-dated infrastructure investments in recent times, they have been often targeting funding of 10 to 20 years in term. In the third image you can see the cost of 10 year money in the table on the left.

After South Australia (1.35% pa), NSW once again takes the cake for the highest cost of capital at a chunky 1.31% pa. Another question I've fielded is how much more do the states have to pay for funding than the federal government, which I guess is pretty topical given both are being asked to do a lot of heavy lifting on fiscal policy.

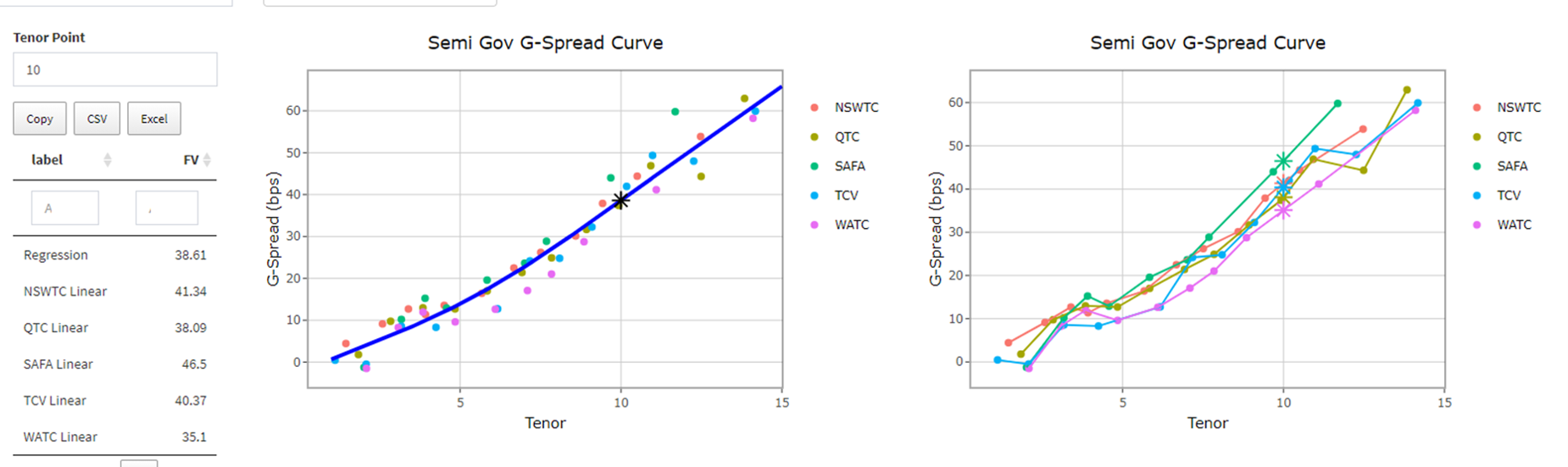

The fourth screenshot below answers this quantitatively by displaying the spread above government bond yields that the states have to service. While the table summarises the data, one can see the spread is fairly chunky: NSW, which again has the dearest cost of capital among the largest states, pays a spread of 0.41% pa above what the federal government has to pay.

The Reserve Bank of Australia's Governor Phil Lowe has put this issue on the table with his suggestion at National Cabinet that the states consider spending another $40 billion over the next two years to support the federal government's expansionary fiscal policy program. Governor Lowe delivered the same message in his parliamentary testimony, specifically citing the ability of the RBA to keep the states' cost of capital low:

To date, I think many of the state governments have been concerned about having extra measures because they want to preserve the low levels of debt and their credit ratings. I understand why they do that, but I think preserving the credit ratings is not particularly important; what's important is that we use the public balance sheet in a time of crisis to create jobs for people. From my perspective, creating jobs for people is much more important than preserving the credit ratings. I have no concerns at all about the state governments being able to borrow more money at low interest rates. The Reserve Bank is making sure that's the case. The priority for us is to create jobs, and the state governments have an important role there, and I think, over time, they can do more. But the federal government may be able to do more as well. We may need all shoulders to the wheel.

Westpac's Chief Economist, Bill Evans, highlights that in the latest RBA board minutes there were several revealing remarks about the states' spending programs, including the often overlooked point that the fiscal policy settings of the states are more important in demand terms than the federal government's policy posture on this front:

Another important change in the Board’s rhetoric is around the commitment to further purchases of government securities. For the first time in the “Considerations” section of the Minutes the Board note – “Members noted that public sector balance sheets in Australia were strong which allowed for the provision of continued support.” In the discussion on the domestic economy further support to the causes of the State and Territory governments was outlined, “Members noted that state and territory governments had played an important role in complementing income transfers …by increasing direct spending on goods and services and job creation….accounted for a larger share of public demand than the Australian government… debt levels relative to the size of the economy were low for Australian and state governments.” This indication of support for the state governments is clear even though the official policy target is restricted to the three year AGS...However it seems reasonably clear that the RBA is committed to supporting the semi government sector’s borrowing requirements as it encourages states to lift their spending. That will happen indirectly through the TFF and the wind down of the CLF, although I expect there will be a significant lift in direct purchases of semi’s by the RBA as we move into the next stages of the budget deficit funding processes.

Not already a Livewire member?

Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

2 topics