The race to build the world’s 5G network

Lazard Asset Management

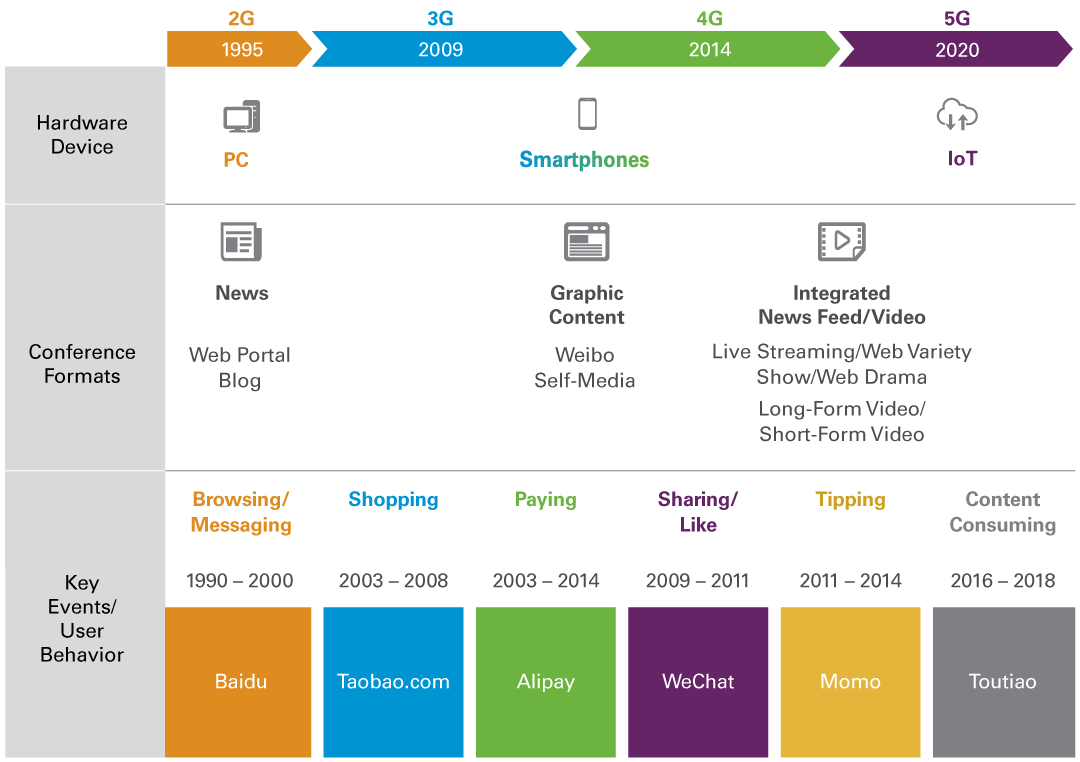

Fifth-generation cellular network standards—5G for short—are the internet’s new new thing. Each of the "Gs" that predated 5G made the mobile internet faster and capable of running more complex, data-heavy applications. From 2G, which made mobile phones fast enough for text messaging, we have come all the way to 4G, which allows us to watch streaming video and run data-heavy applications on our smartphones. The speed and capacity of 5G promises to bring fully into the realm of reality such futuristic concepts as artificial intelligence, virtual and augmented reality, robotics, and the Internet of Things, which allows machines to communicate with one another through internet-connected sensors.

Mobile phones with 5G capability already exist—5 million of them have already been sold in the United States, and those numbers will grow when Apple begins selling its model later this year—but creating a widely available 5G network around the world requires a significant investment in mobile infrastructure.

A handsome reward likely awaits the companies that turn out to be integral in this massive transformation, but this is no ordinary free-market competition.

The Long Game

The race to 5G figures to be a long and costly marathon, not a sprint, with all the technology the 5G network involves. China conceived its 5G strategy a decade ago, when it had only recently acquired 3G capability (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: A Wireless History

Source: Morgan Stanley Research

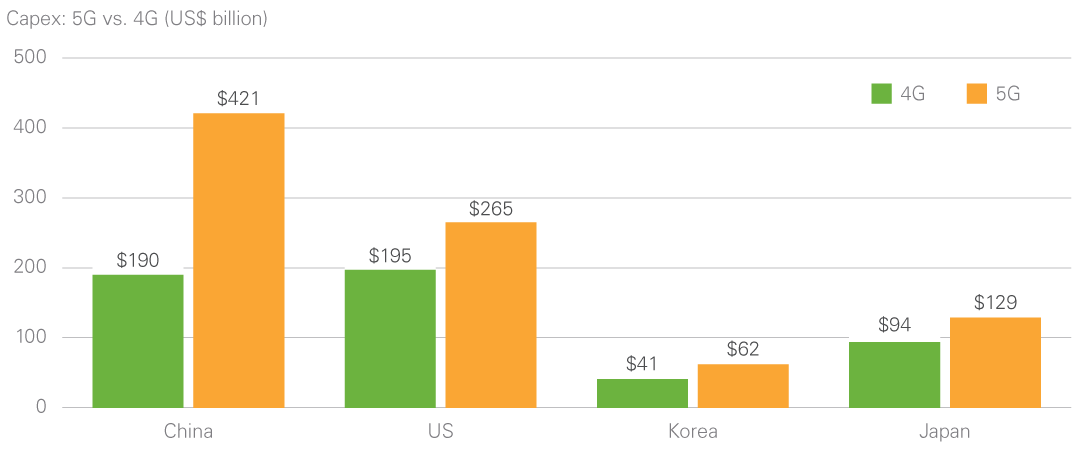

Rather than importing existing 4G technology, China developed its own at a cost rivaling America’s expenditure on its 4G buildout. By many accounts it ended up with a 4G network inferior to what it might have acquired. However, that experience and an enormous expenditure on research and development was crucial in China’s effort to develop 5G before anyone else. Today, China reportedly owns about one-third of the 5G patents on file, a good deal more than those of the United States or the combined nations of Europe. It is investing more than twice as much as the US is in 5G—and nearly as much as the US, Korea, and Japan, the next three national competitors, put together—and plans to have as many as 800 million 5G connections by 2025, nearly half the 1.8 billion that it foresees worldwide (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: China Doubles Down on 5G

As of 23 February 2020. Source: Morgan Stanley Research Estimates

A Virtual Cold War

The US has not taken lightly to China challenging its long-held leadership in global technology. The hostile response goes deeper than purely commercial concerns. The global adoption of a Chinese-designed 5G internet raises existential security issues that only begin with consumer privacy. The new technology will have a central role in automating tomorrow’s factories, regulating its energy grids, and reinforcing national defenses. Such sensitive applications have invited geopolitics into the 5G race, particularly since China has taken an early lead. Along with the United Kingdom, Australia, Japan, Taiwan, and India, the US has gone so far as to ban the use of equipment from Huawei, China’s 5G state champion, in its data network.

Even more damaging to Huawei’s prospects, America has weaponized its computer chips. Notwithstanding the Chinese R&D push, the US holds a substantial lead in chip design, including those used in the third-generation semiconductors needed to run 5G networks. It has barred any manufacturer of US-designed chips from supplying them to Huawei unless the manufacture has been granted a license to ship from the US regulator, who is currently considering applications.

Huawei—with the likely encouragement of the Chinese government, which places a high priority on developing the domestic semiconductor industry to reduce dependence on the United States—has shifted some production of semiconductors for its consumer and mobile network infrastructure product lines to the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), China’s leading domestic chipmaker. In the current atmosphere, the US might well respond by placing it on the so-called Entity List, which would require American companies (and potentially others) to apply for a license before supplying the firm with US-made technology. The Entity List exemptions may extend as well to the third-generation semiconductors Huawei requires for its 5G networks—a sign of how interdependent the world's technology has become despite the nationalistic saber-rattling.

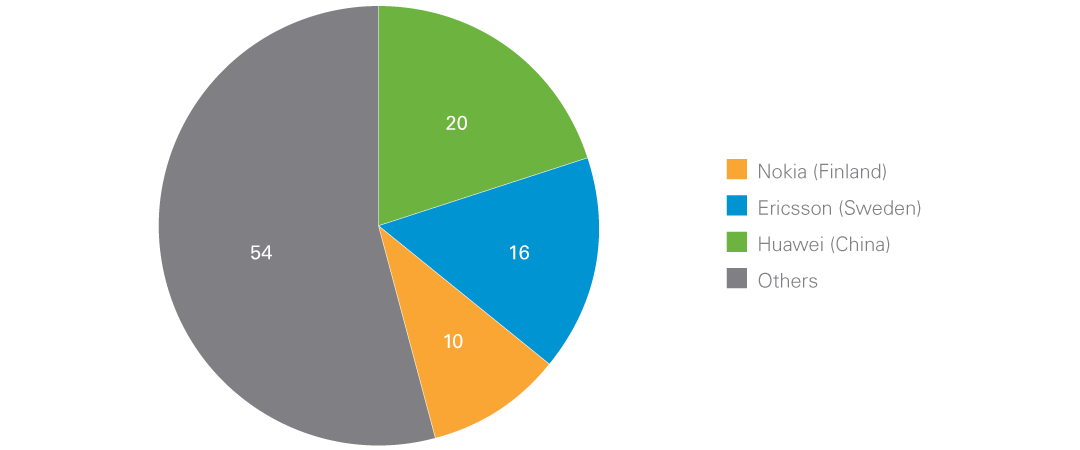

Still, it would be premature to count Huawei out. Although the US holds the weapons in its chips, Huawei commands the battlefield of standards. The firm has seized a leadership role in setting worldwide 5G operating standards. It owns more patents on file with the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP), the international consortium charged with determining those standards, than any other competitor (Exhibit 3). Huawei’s command of the standards may well blunt the impact of the sweeping bans. Even the foremost opponent to Huawei’s ambitions, the US government, is permitting American companies to work with Huawei in formulating 5G operating specs. And as a practical matter, 5G operators in countries that have shut Huawei out may still have to pay royalties to Huawei.

Exhibit 3: Who Makes the Rules Controls the Game

As of August 2020. Source: Cyber Creative Institute, Financial Times

There is also the world outside the developed markets to consider. Many countries in Latin America and Africa, as well as some in Southeast Asia, place their economic interests over national security concerns and are much less likely to exclude Huawei. These countries already have strong trade ties with China and depend on Chinese telecom suppliers. The Chinese companies also provide a palatable price point and offer a viable option at a time when there are few alternatives to Huawei in the US or elsewhere.

Globalisation in an Onshoring World

Despite all the fashionable talk of onshoring in sensitive industries, globalisation is still the lifeblood of the technology world. No one business and no one power—not even nations with the size of China or the resources of the United States—can realise the full potential of an undertaking on the scale of 5G. Samsung in Korea has made a concerted push into 5G. Huawei could face competition on the home front as well. ZTE, Huawei’s principal domestic rival, could step in, as could Xiaomi, the low-cost Chinese handset maker. Also well-placed for the coming 5G battles is the Taiwanese chip fabricator MediaTek. Finally but by no means least, America’s tech titans, Apple, Qualcomm, the other usual suspects, and potential disruptors of the future will surely factor in before the story ends.

Politics may have a short-term role in how the 5G buildout unfolds, but politics will not stop development in its tracks. In the short term, China’s government will likely wait and see how the US presidential election plays out in November, but whatever the result, the country has invested too much to let politics stand in the way. In other words, 5G is moving forward regardless of the presidential election outcome or future political posturing.

Thanks to the R&D effort behind it and its nearly limitless application, 5G is doubtless a technology whose time has come. For investors and entrepreneurs, China’s push into the technology has done more than stir up a geopolitical hornet’s nest. It has served to sensitise them to the magnitude of resources 5G requires and the complexities of the issues it raises. Supplying those resources and mastering those complexities, no matter where in the world the solutions come, holds the prospect of substantial operating profits and generous investment returns.

Get access to tomorrows biggest themes today

For further insights on the latest innovation develops from around the world, hit the follow button below and you'll be the first to read all our wires.

3 topics

Robert is Director and Research Analyst on the Developing Markets Equity team, focusing on the technology sector. He began working in the investment field in 1993. Prior to joining Lazard in 2011, he Director and Portfolio Manager at Merrill Lynch.

Expertise

Robert is Director and Research Analyst on the Developing Markets Equity team, focusing on the technology sector. He began working in the investment field in 1993. Prior to joining Lazard in 2011, he Director and Portfolio Manager at Merrill Lynch.