Five reasons why the RBA was right to slow down and the top is near

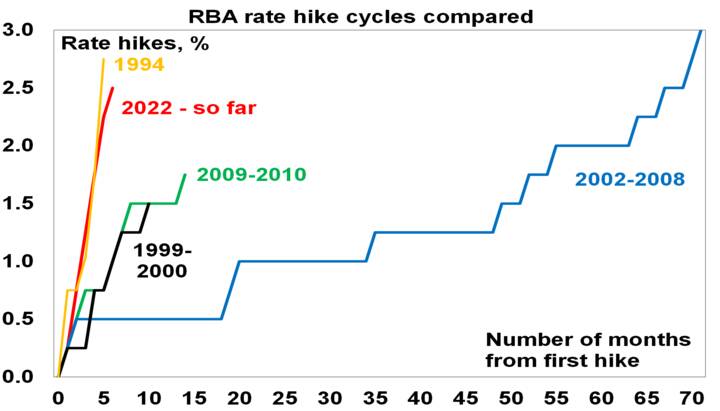

The RBA has increased its cash rate again but slowed the pace to +0.25% which took the cash rate to 2.6%. This was in line with our view and a slowing “at some point” had been flagged by the RBA. In justifying another hike, the RBA noted inflation is still too high and expected to rise further due to global factors and strong demand and that it’s important that medium term inflation expectations remain “well anchored”. But the 250 basis points in rate hikes over six months is still the fastest series of hikes since 1994, so it made sense to slow the pace down “as it assesses the outlook for inflation and growth”.

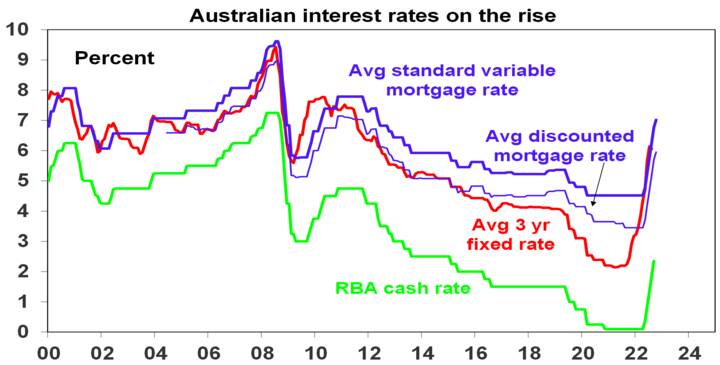

Of course the slowdown in rate hikes to a “business as usual” 0.25% move does not mean the RBA has finished hiking as it repeated that it will do “what is necessary” to get inflation to target and it still expects to raise rates further. Banks are likely to pass the hike on in full to variable rate customers which will take mortgage rates to their highest in ten years.

.jpg)

Five reasons why the RBA was right to slowdown and expectations for a 4% plus cash rate are too hawkish

Getting inflation back under control is critical as a rerun of the 1970s experience of high inflation will be disastrous. So the RBA has been right to sound tough and act aggressively. However, after the most aggressive run of rate hikes since 1994, the RBA was right to slow down the pace of hikes to better assess their impact and avoid overtightening. Here are five reasons why the RBA is likely to remain in the slow lane in the months ahead and why the cash rate won’t have to go as high as the 4% plus the money market has been factoring in.

#1. Monetary policy impacts the economy with a lag

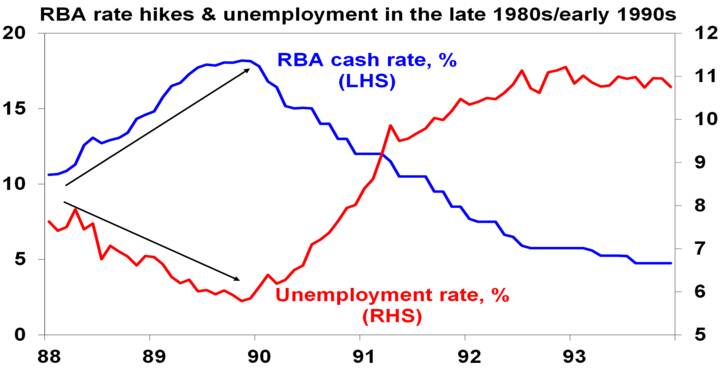

This is because it takes 2-3 months for RBA rate hikes to impact actual variable rate mortgage payments and then several months before this impacts spending. There are then flow on effects to jobs and business investment with feedback impacts on household which can take up to a year. And this lag may have been lengthened by the rise in fixed rate lending around 2020-21 which saw it rise from 15% of total mortgages to around 40%. The lag was clearly evident in the late 1980s and early 1990s – see the next chart.

.jpg)

Unemployment kept falling between 1988 and 1989 - to 5.8% which was considered low at the time after it rose above 10% in the early 1980s - as the RBA progressively hiked rates to 18%. But by then it was too late as the impact of past rate hikes hit the economy hard in 1990 and it went into a deep recession, with the RBA then having to rapidly reverse course as unemployment surged. Of course, things were different back then with very low debt & very high inflation expectations resulting in much higher interest rates than are needed today - but the lags are still relevant. To avoid overtightening as in 1989, the key is to slow down the pace of hikes to allow time for the lags to work – and this is what the RBA now appears to be doing.

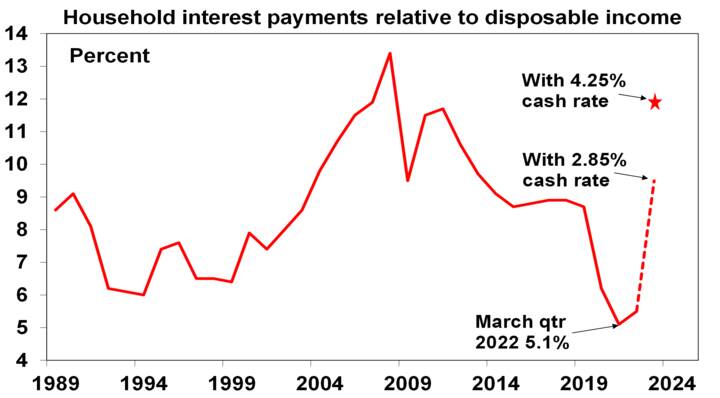

#2. Many households will see significant mortgage stress, which will hit spending from later this year

The 2.5% in RBA rate hikes have already taken us to the 2.5% interest rate serviceability buffer that applied up until last October and are close to bursting through the 3% buffer applying since then. While RBA analysis shows that just over one-third of households with a variable rate mortgage will see no increase in their payments with a 3% rise in interest rates as they were already paying more than they need to they will still be worse off because they will be paying down their debt more slowly. But it also shows that more than a third of households with a mortgage will see a greater than 40% increase in payments. This is about 1.3 million households and would cover those most likely to have to cut back their spending, ie new homeowners often with a young family.

Looked at another way, a variable rate borrower on an existing $500,000 mortgage will see about $75 added to their monthly payment from today’s RBA hike which will take the total increase in monthly payments since April to $740 a month. That’s nearly $9,000 a year which is already a massive hit to household spending power. And there is roughly a quarter of mortgaged households with fixed rates that will see a three-fold increase in their payments when their fixed term expires over the next two years – many of whom are next year.

The surge in house prices, household debt levels and debt principal repayments as a share of household income to record levels over the last 30 years was made possible by falling interest rates to record lows which took household interest payments down to levels not seen over the past 45 years or so as a share of household income. A rise in the cash rate to 4% or more would push total mortgage repayments (ie, interest and principal) to record highs relative to household income.

.jpg)

The combination of a household debt to income ratio which is nearly double US levels and greater sensitivity to interest rate changes (with 60% of mortgages on variable rates and 40% on short-dated fixed rates compared to US borrowers on 30-year fixed rates) means that the household sector in Australia is far more vulnerable to interest rate changes than US households. This means that the RBA can afford to be less hawkish than the Fed.

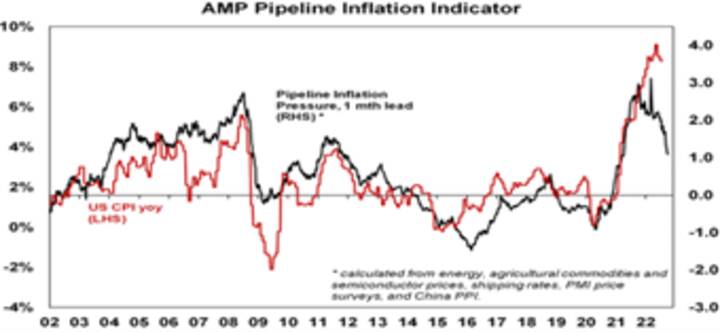

#3. Global inflationary pressures are continuing to ease

This is evident in global business surveys showing reduced delivery times and falling work backlogs, lower freight costs, lower metal and grain prices, and falling input and output prices. As a result, our Pipeline Inflation Indicator is well down from its highs. Consistent with this US money supply which surged ahead of the US inflation spike is falling. Combined this points to downwards pressure on US inflation, which looks to have peaked. Australia appears to be following the US by about six months, pointing to a peak in inflation here later this year.

.jpg)

Related to this, medium-term inflation expectations remain reasonably low suggesting that the task of central bankers should be a lot easier than in the 1970s and 1980s.

#4 Inflation pressures are less in Australia than elsewhere

Inflation is now around 7% yoy compared to over 8% in the US and 10% in Europe and wages growth is about half US levels. So there is no need to match other central banks' rate hikes.

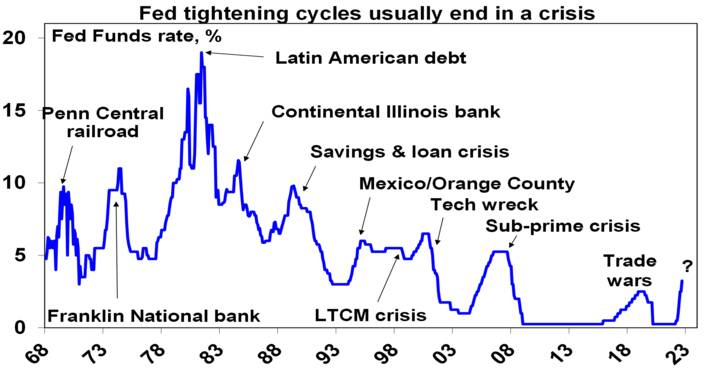

#5 Rising global recession risk

The 23% plunge in global share markets, falling commodity prices, central banks including the Fed willing to risk recession, the Fed’s record of tightening cycles ending in a crisis (next chart), the rising skittishness of financial markets, the deteriorating global growth outlook and domestically very low consumer confidence and rapidly weakening housing indicators warn of much weaker conditions ahead which will hit jobs & drive weaker inflation. Aggressively tightening into all this without pausing for breath risks knocking the Australian economy into a recession we don’t have to have.

.jpg)

Concluding comment

Given the need to assess the lagged impact of rate hikes and the rising risk of recession globally, the RBA was right to break from the hawkish global central bank consensus and slow down the pace of hikes. We see another 0.25% rate hike next month taking the cash rate to 2.85% which we still expect will be the peak in the cash rate, albeit the risk is on the upside to 3.1%. We still see rates falling late next year

Never miss an update

Enjoy this wire? Hit the 'like' button to let us know. Stay up to date with my content by hitting the 'follow' button below and you'll be notified every time I post a wire.

Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

3 topics