The toughest questions in investing, as answered by UBS Asset Management

At the best of times, investing is not exactly the easiest pastime. You have to know why you want to make money, where you want to make it, and how you want to do it, then execute the strategy. And even then, the market may have other plans leading to more than a few head-scratchers.

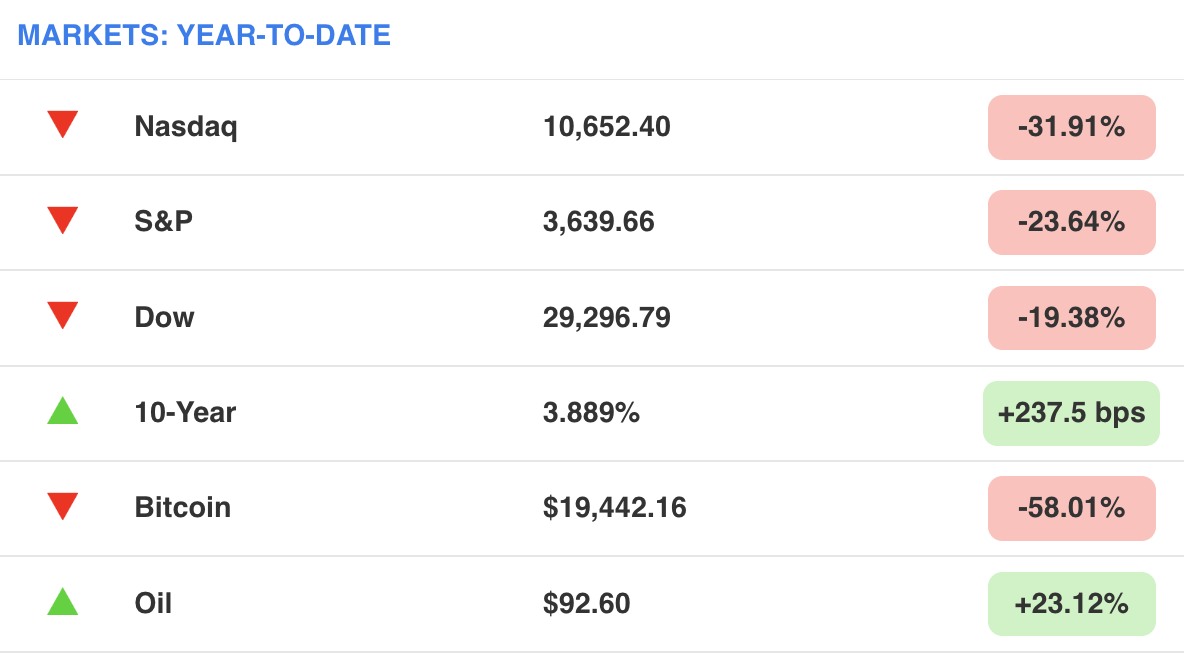

Then, there's investing in 2022. As of October 10th, the NASDAQ is down 32% year-to-date, the S&P 500 is on course for its worst year since 2008, the price of crude oil is up 23%, and the Australian dollar has had a near-15 cent trading range in the last year. It's been a wild year, and we don't have to tell you why.

No doubt you have questions about how this year has panned out for investors - but I'm sure the most important answer you just want to know is "when". When will the market carnage in bonds and equities end? Where will house prices bottom out? When will global central banks stop hiking interest rates?

These, and many other questions, are the subject of two new compendiums put together by UBS' global markets team. In this wire, we're going to go through eight of the most pertinent questions to Australian investors - and their responses.

The elephant in the room: Has inflation peaked?

Every time I hear this phrase asked, I have an urge to turn into Eddie McGuire because it really is the million dollar question. But unlike Eddie, he can't even give you options because the answer is so open-ended. Most research houses have US inflation peaking in some shape or form next year, while others won't even start predicting when the peak is. They do, however, point to a slew of data such as falling shipping costs, a fall in crude oil prices (from a very high peak), and consumer inflation expectations as reasons for why the peak may not be far away.

So what does UBS think? Analysts led by global head of economics Arend Kapteyn argue the data shows inflation is rolling over - but that it's still too soon to know for sure.

"A significant part of the 'broadening out' of inflation we have seen in 'core' may simply be the knock-on effect (with a lag) of the energy price shock," the note read. The bad news is that UBS still expects Brent crude oil prices to come in at US$100/bbl by the end of 2022 with not a whole lot of reprieve in 2023.

So, about those central banks...

The other big question in town is simple - where and when is the endgame for central banks? In this context, you probably think of the Reserve Bank followed by the Federal Reserve. But terminal is not the same as neutral - and UBS argues that the question investors need to be asking is not where "restrictive" is but where the long-run average will be following the pandemic.

And speaking of the pandemic, one of the hallmarks of the last two years has been the wide use of unprecedented monetary policy measures - or what the punters call free money. Although that process is winding down, governments and central banks alike can still add liquidity to the system in other ways. But won't that keep inflation stubbornly high? Not necessarily, they argue.

If you want an example of that in action, look at the Bank of England. After the UK mini-Budget which sent the Pound perilously close to parity against the US Dollar, the Bank of England decided to intervene in the bond market instead of doing what other traders wanted (hike interest rates in an emergency move). But the UK's move had far wider implications for global bond traders, as New York-based analysts Evan Brown and Luke Kawa worked out.

"Central banks are prepared to push back against price action judged to be excessive or counterproductive to their goals," Brown and Kawa wrote in a note released on October 6th.

The other scenario: stagflation

While all the chatter is around the "R" word (recession), there are some investors and professionals alike who are more worried about a persistent case of stagflation. The difference between the two are minute but the effects can last for years. Stagflation was last felt (in the modern sense) during the oil crisis of the mid-1970s. Stagflation is rarer than a recession and can be likened to a worst-case scenario because it involves slow economic growth coupled with inflation for a long time (years, as supposed to a few quarters).

And the reason searches and mentions of stagflation have been going up is because of what happened during the mid-1970s. So naturally, the question is being asked - when are energy prices going to cool so that we avoid a 1970s-type situation?

The short answer is yes, but not in every region - and thankfully, not Australia.

Conclusion? Breathe easily.

So what does this all mean for asset allocation?

This is where we return to Evan Brown and Luke Kawa. Earlier, we alluded to the fact that yields around the world were affected by the Bank of England's recent emergency measure. But we did not mention that the analysts thought this move actually balanced out the risks for investing in bonds.

Another question the analysts got - is the US Dollar going to keep storming higher? For those in the know, the US Dollar Index has been the trade of the year and continues to shatter its own record at the expense of gold and US companies with overseas earnings. Their answer? Yes.

"Federal Reserve policy will continue to buoy the US dollar, in our view, as tightening will likely continue without a pivot to easing until material evidence of labor market weakness emerges or inflation returns much closer to target. Neither of those outcomes is probable in the near term," Brown and Kawa wrote.

And finally, what does all this mean for equities? The short answer is that the road ahead will be tough but low expectations could provide some (if only, temporary) upside.

"We believe that unless there is a fiscal or geopolitical policy change that provides strong cause to believe that revisions will soon turn, this downward pressure will remain a headwind for risk assets," Brown and Kawa said.

2 topics