The underemployment problem

The RBA has published a fascinating new research paper on "underemployment", which has increased noticeably since the GFC. The underemployment rate is defined as the share of workers in the economy who want to work, and are available to work, additional hours. That is, folks who are underemployed represent additional potential labour supply above and beyond those who are unemployed.

Crucially, the RBA finds that the underemployment rate is a better predictor of wages growth than the unemployment rate (which my colleague Kieran Davies showed is being heavily biased---in extremis by as much as 2.4 percentage points---by the exodus of foreign workers, which could be temporary).

The RBA has further concluded that because of the significant increase in the underemployment rate in recent decades, the more conventional unemployment rate may have to fall further than it has historically before Australia experiences strong and sustainable wages growth of 3% to 4% pa. The "sustainable" caveat is important here because as Australia gradually reopens its borders, we are almost certain to have a huge influx of new labour supply (ie, skilled migration, students, and tourists), which will put downward pressure on wages and upward pressure on the jobless rate.

I have enclosed some key excerpts and charts from the RBA's paper for your viewing pleasure.

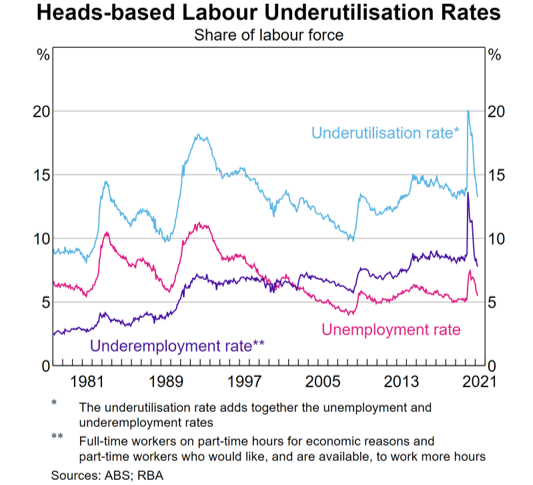

Underemployed workers represent additional labour supply that can be called upon before there is upward pressure on wages...Underemployment in Australia has been increasing for several decades, driven by both structural and cyclical factors; in contrast, over the same period the unemployment rate has fluctuated but has broadly moved lower (Graph 1).

The heads-based underemployment rate has trended up over time, and has been around historically high levels for several years (looking through the pandemic-related spike in 2020). The hours-based measure has also moved higher over the past 10 years, although to a lesser extent. In April 2021 the heads-based underemployment rate was 7.8%; that is, nearly 1.1 million people were underemployed, out of the total labour force of a little under 14 million people. Of these, around 1 million were part-time underemployed people, which was around one-quarter of all part-time workers.

Given the willingness of underemployed workers to work additional hours, underemployment clearly represents an amount of potential labour supply that can be drawn on without an increase in measured employment. Importantly, these are additional hours that people are prepared to work at prevailing wage levels; employers may not need to increase wages in order to source additional labour supply.

Underemployed workers may also, in the first instance, be looking to increase hours or maintain flexibility in working hours rather than bargain over wages.

The importance of underemployment as a factor shaping wage outcomes has been receiving increased attention among policymakers and researchers (Lowe 2019). Internationally, Hong et al (2018) find that, across developed economies, involuntary part-time employment appears to have weakened wages growth and represents additional slack in the labour market. Similarly, Bell and Blanchflower (2021) find that some measures of underemployment have been a better predictor of wages growth than the unemployment rate since the GFC in a number of countries, including the United Kingdom and the United States.

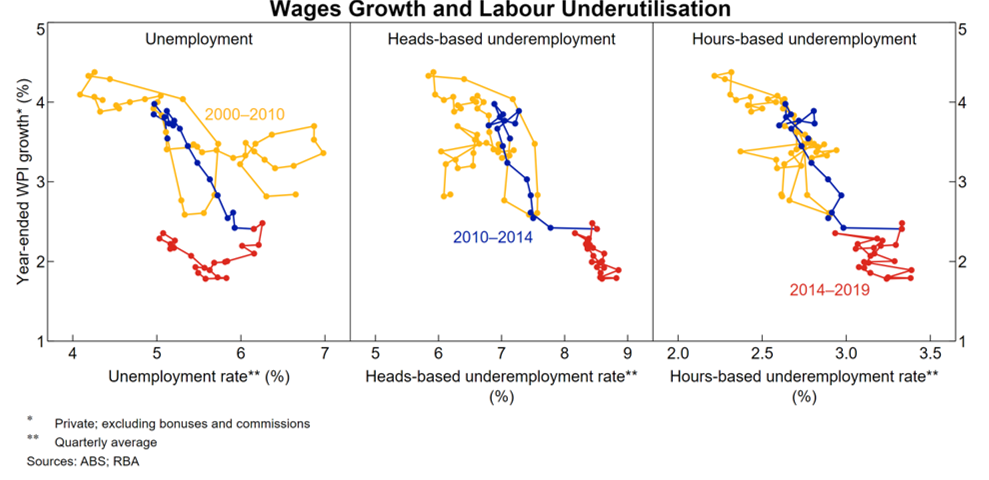

The move higher in underemployment in Australia over the past decade or so appears to have had some relationship with observed wages outcomes over this period; higher rates of underemployment have generally been associated with slower rates of wages growth (Graph 11).

In contrast, there has been a less clear relationship between wages growth and changes in the unemployment rate, particularly in more recent years. Recent discussions of the Australian experience include Bishop and Cassidy (2017), Chua and Robinson (2018) and Treasury (2017).

Because of the additional spare capacity represented by an increase in underemployment, observed wages growth may be slower for a given level of the unemployment rate. The increase in the underemployment rate has therefore likely contributed to various researchers' finding that the level of unemployment consistent with stable wages and inflation has declined over the past 15 years or so in Australia; see discussions in Cusbert (2017) and Ruberl et al (2021).

Abstracting from other changes that have occurred in the economy, the upwards trend in the underemployment rate may mean that the unemployment rate would need to decline by more than has previously been the case before wage pressures start building strongly. Certainly, this was the pre-pandemic experience for a number of other advanced economies; see discussions in Arsov and Evans (2018) and Ruberl et al (2021).

Access Coolabah's intellectual edge

With the biggest team in investment-grade Australian fixed-income, Coolabah Capital Investments publishes unique insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid leveraging its 14 analysts and 5 portfolio managers. Click the ‘FOLLOW’ button below for more of our insights.

2 topics