Thinking about industrial (and Qantas and Netflix)

In global real estate, there has been no sector that has enjoyed more demand tailwinds over the past 10 years than industrial. Naturally, the trend in online retail has helped, but the emergence of COVID added to this underlying demand. On top of that, the ‘secular demand story’ included drivers such as ‘reshoring’, ‘supply chain reconfiguration’, ‘redundancy / obsolescence’ – the list goes on.

The 10-year demand story has pushed industrial cap rates down, rents up, and capital values ever higher. Between 2011 and 2021, the share price of Prologis – the world’s largest industrial REIT – increased six-fold, or a ~500% return before dividends.

So much for “boring old real estate”!

But after another positive round of earnings reports from the industrial REITs last month (accompanied by the standard earnings upgrades etc), on 29 April the shoe dropped. Amazon, the largest user of industrial /logistics properties in the world (and largest tenant for most industrial REITs), announced it had “too much warehouse space right now” . The following day, industrial REITs promptly dropped ~10%. The news got worse when stories emerged the following month that Amazon was seeking to sub-lease up to 30 million square feet , or roughly 8%, of its total domestic needs.

How did it come to this? To answer this, it’s worth reviewing other industries with similar “secular demand” stories, how they performed, and what lessons can be learned.

Thinking about Qantas

In 1995, the IPO of Qantas was a big event. The national carrier, previously owned by the federal government, was about to be listed and shares directly offered to ordinary Australians. If a sense of patriotic duty was not enough to buy shares, there was a good growth story to tell. Long-term travel demand had grown historically and was expected to continue – it was ‘secular growth’. The Qantas brand was globally regarded as reliable and safe.

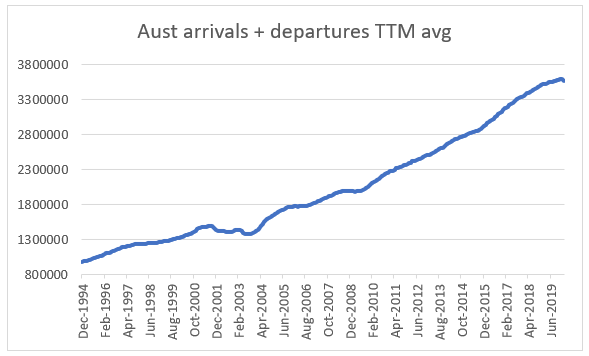

The secular demand story played out – probably better than first envisaged. Below is the growth of total inbound / outbound visitations to Australian since 1995 (total trailing 12 months) up to February 2020. So, how did Qantas perform given the three-fold increase in international visitations?

Source: ABS, Quay Global * TTM = Trailing twelve months

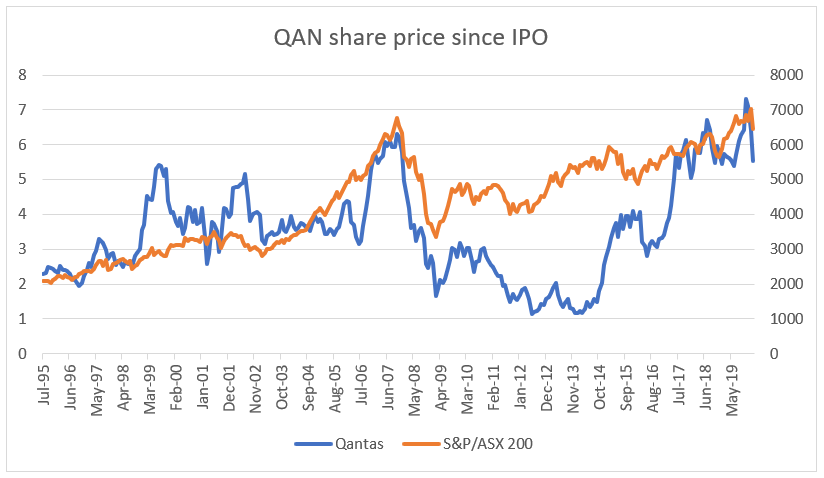

Well, it’s been okay, without really shooting the lights out. It has generally performed in line with the broader equities index.

Source: Bloomberg, Quay Global Investors

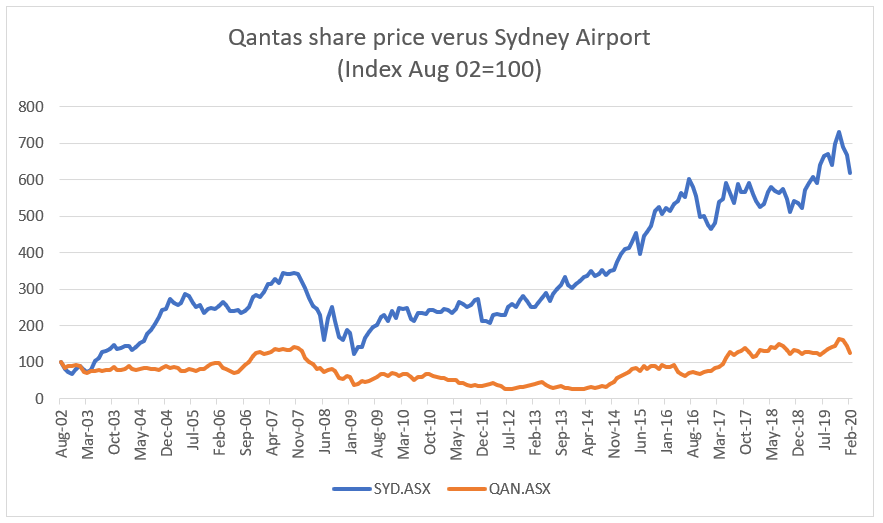

There is another company that was also a clear beneficiary of the secular demand in travel – Sydney Airport, which listed in 2002. The 18-year performance relative to Qantas is stark (to February 2020, eliminating COVID-related distortions).

Source: Bloomberg, Quay Global Investors

Why the disparity? Both industries are exposed to the secular demand story. Both are capital intensive.

The reason is clear (at least to us) – it’s not just about secular demand, but also the elasticity of supply, or barriers to entry. Airlines have very little; airports have heaps.

Thinking about Netflix

For readers interested in the wider equity markets, the ‘normalisation’ of our post-COVID world has been just as brutal in other areas, especially technology stocks.

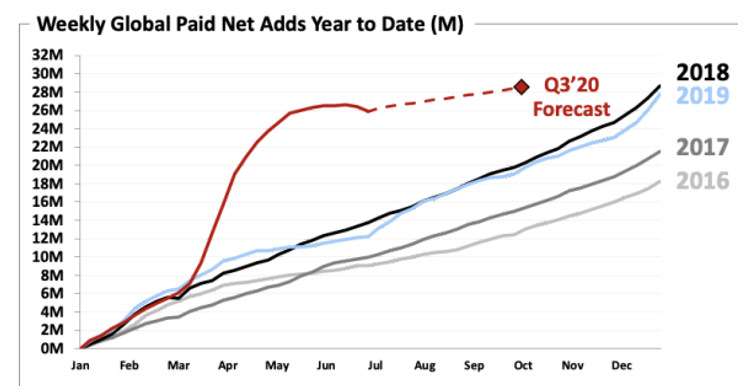

One of the darlings of the COVID world was Netflix. In June 2020, Netflix published the following chart on user subscriptions. COVID accelerated existing trends as consumers, flush with stimulus cash and nowhere to go, turned on their devices and immersed themselves in binge-watching shows. It was another secular demand story.

Source: Netflix Investor letter, Q2 2020

Since peaking in October 2021, Netflix shares are now down 73%. In the battle between accelerating trends and mean reversion, mean reversion appears to be winning.

It’s not the secular demand story has gone away – after all, cinema visitations are still well below pre-COVID numbers. But it does show that extrapolating trends from a once-in-a-century pandemic can be dangerous.

Thinking about industrial

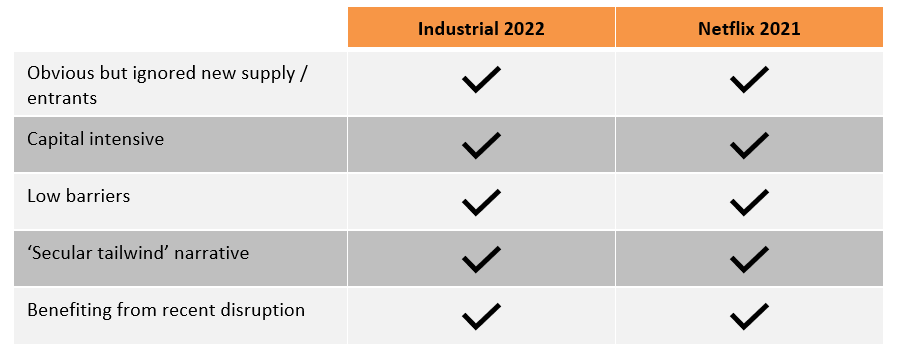

When thinking about the Netflix journey, we find a number of striking similarities with industrial property.

One of the more important lessons in real estate is to differentiate between commodity and non-commodity real estate. Like airlines, commodity real estate generally has low barriers to entry, which means no matter how good the secular demand story, if there is a profit from delivering supply, then supply will be delivered.

A consequence of low cap rates and high values is that it sends a signal to developers and others with capital to supply the market with new product. For industrial property, the green light to build has been burning brightly for several years. The increasing supply was masked by short-term demand boosts from COVID, then ‘just in case’ inventory management, then a surge in demand for consumer goods.

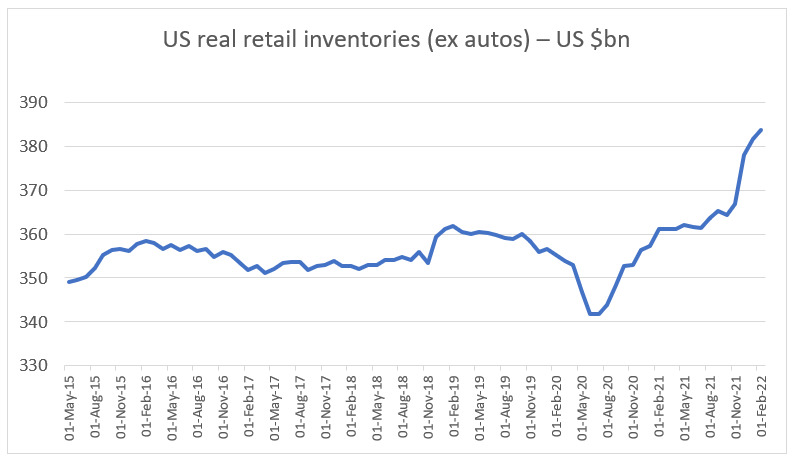

The post-COVID events described above caused an enormous surge in retail inventories (~10% in real terms) as depicted in the chart below, which we think is something of a Rorschach test for property investors. Bullish investors see this as underlying industrial demand. Bearish investors see this as demand already satisfied and prone to normalisation.

Source: Bloomberg, Quay Global Investors

It turns out normalisation was staring everyone right in the face. The data has been clear for many years now. Online retail sales (as a share of total sales) have been moving back to trend since June 2020.

Source: US Census Bureau, Quay Global Investors

Of course, in the context of an entire industry, Amazon (and online retailing) is only a relatively small user of warehouse / logistics. So, on its own, this may not be a big issue.

For real estate investors, the question is whether Amazon is the only user with excess warehouse needs, or is Amazon the only retailer that is honest about the current environment?

The issue does not appear to be only affecting pure online retailers. In the current US reporting season, traditional retailers are reporting substantial inventory increases well in excess of sales, including Dicks’ Sporting Goods (+40%), Abercrombie (+45%), Target (+43%), Walmart (+24) and Kohls (+40%). It is hard to imagine this not happening across other unlisted retailers’ businesses. These levels of inventory (already warehoused) need to unwind for the new post-COVID reality.

Concluding thoughts

When thinking about industrial property, we can’t help but see some parallels with other industries and companies. Both Qantas and Netflix inform us that secular demand on its own is not enough to justify or deliver sustainable outsized returns. For that, one also needs barriers to entry (a la Sydney Airport). And for all the talk that industrial landlords only own high barrier infill locations, the same landlords routinely report record new development pipelines. Curious.

Where to from here?

Amazon could well be a bump in the road. Time will tell.

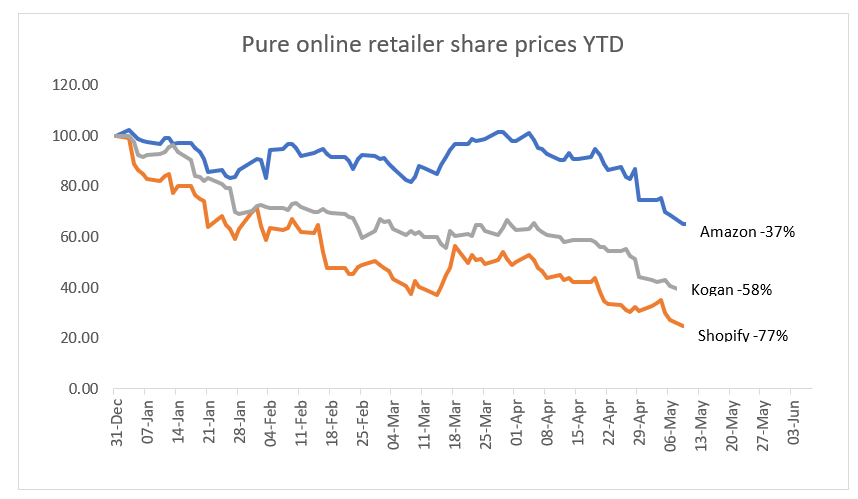

In 2015, well before the decline in listed and unlisted mall values, the major tenants of US shopping centres began to suffer a significant fall in share price. Bed Bath & Beyond, Macy’s and The Gap all suffered 50%+ declines from their 2015 highs. This turned out to be a good leading indicator for mall REITs like Simon Property Group, which peaked in price the following year (June 2016), around the same time we published our article, Thinking about malls.

Share prices are not always efficient, but can be informative. The recent performance of online retail stocks will be of little comfort to industrial landlords. Is this just the unwind of excessive valuations, or a signal that online retail penetration is nearing saturation? Or both, perhaps?

Source: Bloomberg, Quay Global Investors

There is no doubt there remains a compelling secular long-term demand story for industrial property that extends beyond e-commerce. But despite the secular demand, low barriers to entry mean industrial property is still a cyclical asset class. And more than any other investment, for cyclicals, price matters.

Investing in global listed real estate

Quay Global Investors, a Bennelong Funds Management boutique, focuses on the preservation and creation of wealth through innovative strategies in real estate securities. For more insights on global property, visit Quay’s website.

3 topics

2 stocks mentioned

2 funds mentioned