This could take a while

Orbis

Typically, bubbles can take years to wash out, and whatever the recipe for the “perfect” bubble may be, conditions of 2021 can’t have been far off. Near zero interest rates and stimulus cheques made money seem free, and governments imposed lockdowns that made normal spending impossible—all but guaranteeing that all that “free money” would be used for speculation instead.

The frenzy thus created gave us meme stocks, dogecoins, and, most bizarrely of all, the Bored Ape Yacht Club, which describes itself as “a collection of 10,000 unique digital collectibles living on the Ethereum blockchain.” That’s right, 10,000 “unique” collectibles (no irony), which at their peak in May traded for $420,000 a piece, with one fetching a price of $3.4m. Dutch tulip bulbs, stand aside.

The stockmarket was not spared its share of speculation. The same recipe led to booms in cash-gushing tech firms, cash-torching tech firms, metaverse stocks, electric vehicle outfits, and any company with the intoxicating whiff of disruptive innovation. Many of those stories started with a kernel of truth, but as Seth Klarman puts it, “at the root of all financial bubbles is a good idea carried to excess.”

Anyone with paper to sell took advantage of that excess. Tesla sold $12 billion, or about one Nissan Motor Company, worth of shares. Whatever the motivations of the offsetting buyers, long-term intrinsic value doesn’t seem to have been high on the list—the average Tesla share is bought and sold more than six times a year. 2021 set all-time fundraising records for stocks, corporate bonds, leveraged loans, blank cheque SPACs, private equity funds, venture funds, and crypto assets. Financial promoters became celebrities, and celebrities became financial promoters.

Exciting projects were lavished with cash, while boring businesses were starved of it. We got a junk surplus and a food shortage. Shortages in things people actually need led to the sharpest inflation the West has seen in decades, and in 2022, central banks finally responded by taking the free money away.

Now that money has a cost again, the craziest assets have started to crash. The price of the record-setting Bored Ape is now down by 97%. Dogecoin has lost 89% of its joke value, and Bitcoin and Ether are down 73% from their peaks. Some of those financial promoters have been arrested for fraud, and some of those celebrities have been sued.

In financial markets, cash has dried up, with the most speculative shares the hardest hit. Shares of Carvana, which bought used cars sight unseen to be sold in vending machines, are down 98% from their peak. Those of Nikola, which rolled a truck down a hill and saw its value eclipse General Motors’, have fallen 96%. Money-losing tech companies have lost 80% of their value on average, as has the fund most enamored of them. In the US, the Nasdaq is down by a third from its peak, and the World Index by nearly a fifth.

So where are we now?

Bored Apes still change hands for $85,000 each. The joke dogecoin still has a $9.5 billion market cap. GameStop, which sells downloadable games in physical stores, is valued more than 10 times higher than it was in the pre-meme days, while AMC, another meme stock which operates silver screens and now, apparently, silver mines, also trades at a multiple of its pre-meme value. Tesla’s market cap has more than halved from $1.2 trillion, but is still more than the next four largest automakers combined.

It usually takes a long time and a lot of pain for bubbles to deflate and valuations to return to less exuberant levels. From the peak of the tech bubble, it took three years for the market to hit bottom, and shares classified as “value” beat those classified as “growth” for the following six. From that relative high, value then lagged growth for the following twelve years. It would be strange indeed if a single year completely unwound the biggest bubble in living memory.

In part, that is because we were starting from such an extreme place. By 2021 corporate profits reached record levels relative to gross domestic product, stockmarkets traded at record multiples of those record profits, and within stockmarkets, the cheaper stocks traded at record discounts.

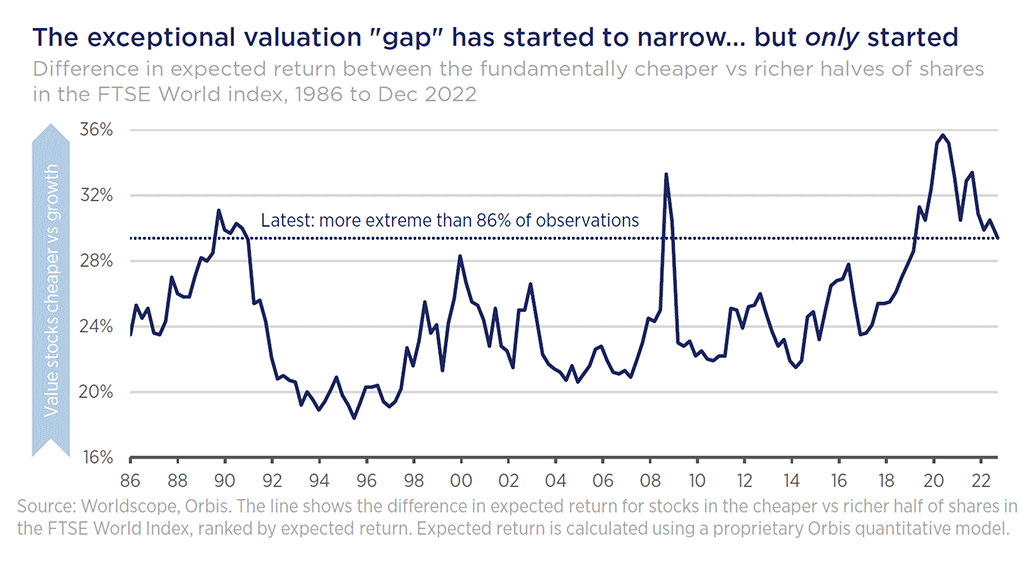

From that starting point, it’s clear the full measure of pain has still yet to be felt. Profit margins and earnings expectations are still very high, as is the dollar. Stock valuations have come down, but not compared to bonds. Most importantly for us, and most encouragingly, valuation spreads remain exceptionally wide. The fundamentally cheap stocks in the market remain unusually attractive in relative terms.

As sanity is restored to valuations, that can drive very healthy returns for unloved shares. Today, the Orbis Global Equity Strategy has its strongest ever tilt towards value. Broadly, we have found more of this value outside the US, and in businesses that haven’t had their valuations inflated by supernormal earnings or very high multiples.

One area we’ve discussed before is energy, which was up 45% this year and is responsible for most of value’s outperformance vs growth. Orbis Global held few energy shares at the start of the year—a mistake in hindsight—and has increased its exposure over the past several months. We continue to find energy shares attractive, and in our view almost all of their outperformance can be explained by improving fundamentals rather than richer valuations.

But there is a silver lining to energy’s outlier performance—cheap shares in other areas remain extremely repressed. Banks, for instance, are down more than 10% this year despite being another classic “value” sector that stands to benefit from a combination of low starting valuations and favourable exposure to the changing economic regime.

When interest rates rise, banks can earn a wider spread between the interest they charge on loans and the interest they pay to depositors. The impact on their profits can be transformational, and if the banks can pay out those profits, they can be rewarded with much higher valuations.

Over the last 13 years, banks have effectively been in altitude training. Near-zero interest rates hurt their lending margins, while regulations have limited their growth and payouts to shareholders. As the environment shifts, they are coming out of altitude training ready to run at sea level.

We have found increasingly compelling opportunities among banks, and they now represent 15% of the Strategy. While we see opportunities globally, financials in Asia generally seem a bit behind those in Europe, which seem a bit behind those in the US.

US banks look less interesting than their foreign peers. They are further along in a favourable economic cycle, and trade at premium valuations, despite not generating sufficiently higher returns on equity.

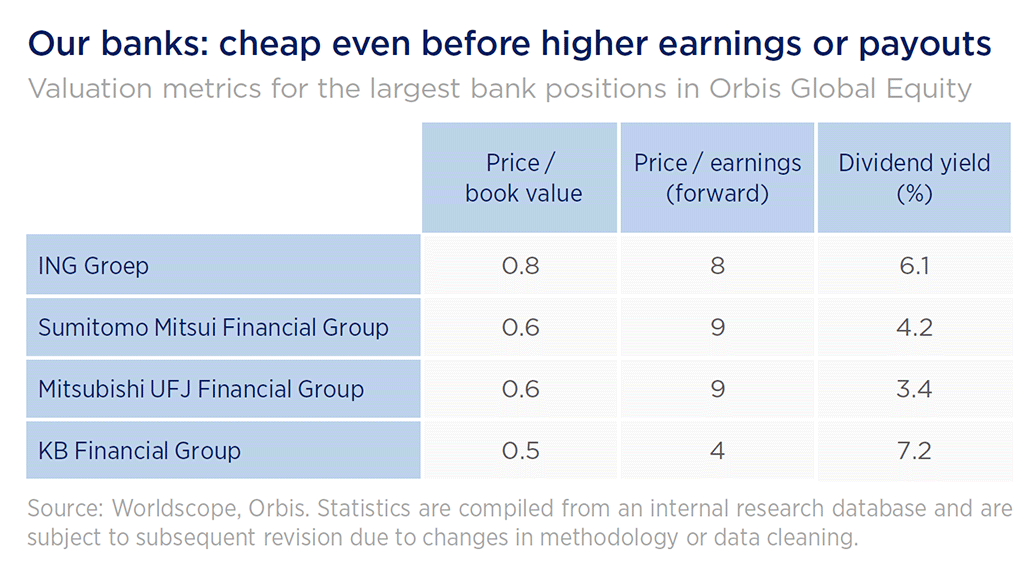

In Europe, we have long found banks ING Group and Bank of Ireland attractive. Both are well capitalised and should be able to earn competitive returns over the long term, but both have traded at a steep discount to book value and at single digit multiples of earnings.

Japan’s banks appear especially attractive. It’s said of banks that you write bad loans in the good times, and good loans in the bad times. There have been a lot of bad times in Japan since its bubble burst in 1990. In general, these banks have their balance sheets in order, they’re relatively well-capitalised, and they are in a supportive environment where regulators want them to earn more money and are happy for them to pay that out to shareholders. On current profits and payouts, banks like Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group and Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group trade at 8-9 times earnings, with dividend yields of about 4%—already appealing.

But where Japanese banks could truly shine is if interest rates rise in Japan. Though the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, and Bank of England have all been racing to increase interest rates, the Bank of Japan has stood alone, keeping negative short-term rates, and pinning the yield on 10-year Japanese government bonds.

With inflation now running well above the official 2% target and the Japanese yen having touched decades-low levels against the dollar, the Bank of Japan’s policy has begun to come under pressure. Interest rates may soon have to rise. If they were to rise from zero to 2%, the earnings of Japanese banks could approximately double, leaving them on 4-5 times earnings with 8-10% dividend yields—far too cheap. With the stocks trading at a 40% discount to book value today, we pay very little for that upside potential. When, or indeed whether, such a policy shift may come, we cannot be sure. But the tweak in yield curve control just before year-end is a positive sign of change.

The Japanese banks are paying dividends, but earnings are depressed. The Korean banks are the other way round. They have the earnings power, but not the payout ratio. Korea’s banks have made faster progress than their Japanese counterparts in terms of earnings recovery, but much slower in shareholder returns. This, too, may be changing, as activist investors begin to push for reform, emboldened by the appointment of a more shareholder-friendly leader of the country’s financial regulator. With dividend yields already high, at 7% for KB Financial, Hana Financial, and Shinhan Financial, increased payouts could make yields too high to ignore, attracting investors. Higher payouts also improve returns on equity, because there is less excess capital sitting unproductively on companies’ balance sheets. Higher yields and higher returns on equity should prove a good recipe for higher valuations.

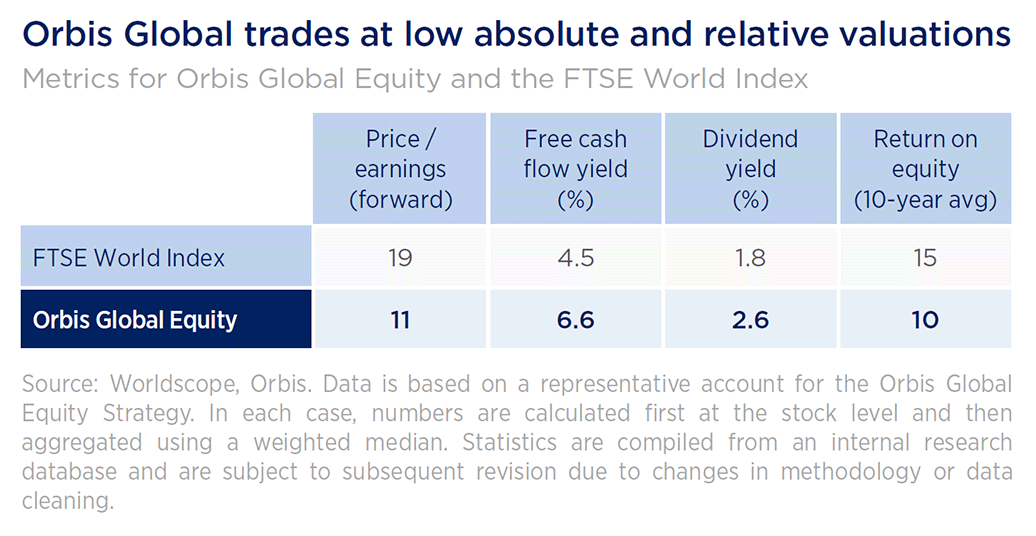

These bank positions contribute to a portfolio that we believe offers much better value than the benchmark, trading at a 40% discount on a price-earnings basis in aggregate. And while the companies Orbis Global holds generated lower returns on average than the average stock in the benchmark over the last ten years, we think their businesses are much better positioned for the conditions that could prevail over the next ten. With valuation gaps still a long way from normal, the value we are finding in the portfolio leaves us very excited about the relative returns of the Orbis Global Equity Strategy. With valuations this modest, we also have a constructive view of the Strategy’s absolute return potential, despite reasons to remain cautious about broad market returns.

Different for good reason

The most lucrative ideas are often in unpopular or ignored areas. We have been confidently investing in unpopular or ignored stocks for over 30 years, unearthing companies trading for less than they are worth, rather than timing market trends. Find out more

Graeme joined Orbis in 1997 as an analyst, and has worked in the areas of risk management, quantitative analysis, and Australian equities. He holds a doctorate of Philosophy (University of Cambridge), and is a Chartered Financial Analyst

Expertise

Graeme joined Orbis in 1997 as an analyst, and has worked in the areas of risk management, quantitative analysis, and Australian equities. He holds a doctorate of Philosophy (University of Cambridge), and is a Chartered Financial Analyst