Three reasons why an RBA “pause” on interest rates is a bad idea

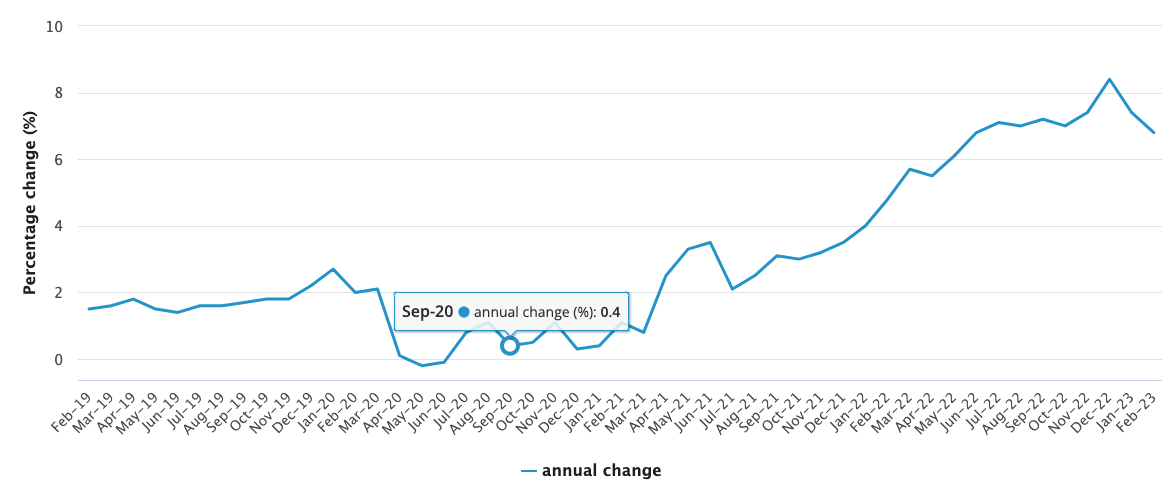

The monthly consumer pricing index indicator showed annual inflation eased to 6.8% from 7.4% last month - lower than the 7.2% that was widely anticipated.

Compiled by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, this monthly measure doesn’t factor in the full range of goods and services considered in the quarterly CPI figure, so isn’t the RBA’s preferred inflation tracking metric. But it captures a subset of the same data, combining information that’s collected monthly, quarterly and annually to provide a more frequent look-through of inflation.

The latest print showed the largest price rises were in Housing (+9.9%), Food and non-alcoholic beverages (+8.0%) and Transport (+5.6%).

Australia's monthly CPI indicator, annual movement

What does this mean?

GSFM investment strategist Stephen Miller notes, in a recent update, that this week’s better-than-expected monthly CPI indicator has raised the prospect that the RBA may "pause" increasing the policy rate when it meets next Tuesday. This follows on from the RBA’s March meeting, where a shift in the tone of language suggested a pause in hiking the policy rate would be on the table for the RBA Board when it next meets on Tuesday 4 April.

“Certainly, the decline to 6.8% in February from 7.4% in January and 8.4% in December is unambiguously good news,” says Miller.

“However, I do not think it is sufficient for the RBA to hit the "pause" button.”

Three reasons why a pause is a bad idea

1. The monthly indicator has only abbreviated coverage of the basket of goods measured by the quarterly CPI. “And in any case, inflation remains at elevated levels in an absolute sense and relative to elsewhere in the developed country complex,” Miller says.

2. Seasonal factors are responsible for some of the decline. When seasonally adjusted (the monthly CPI figures aren’t, while quarterly numbers are) Miller argues inflation actually slowed by just two basis points to 7.1% in February.

3. Inflation doesn’t look to have peaked yet, when other important measures of inflation are also considered.

“My view remains that the policy rate needs a ‘4 handle’ for the RBA to contain inflation adequately,” says Miller.

He notes that the RBA Governor, Philip Lowe, recently emphasised that decisions on policy rate increases are “data dependent”. He cited four key indicators that are also critical in determining whether the central bank hikes, pauses, or reduces the policy rate.

- The March NAB Monthly Business Survey

- February Labour force data

- February Retail trade data

- Monthly CPI indicator

Miller believes the first two key pieces of data “unambiguously move the policy rate calculus toward a further increase in April.”

“Measures of the Australian ‘inflation pulse’ from the NAB Survey indicate that inflation pressures remain extremely elevated into the March quarter 2023,” he says.

Miller notes that the three-month annualised measures of labour costs and retail prices are at 10.2% and 9.5%.

“While they are down from their peaks, they remain at historically high levels compared with the trimmed-mean CPI. That implies some upside risk to the RBA’s current trimmed-mean CPI inflation forecast even if the monthly indicator suggests otherwise,” he says.

The productivity decline

And in December, quarterly national accounts showed a steep fall in productivity: GDP per hours worked fell 3.5% over the year to the December quarter of 2022. This means that unit labour costs (the most relevant labour cost gauge for inflation) increased by more than 7% over the same period.

“That may indicate that inflation, rather than reaching a peak, might simply be at a plateau, or at the very least, that the path back toward the RBA inflation target might be a lot more elongated than currently anticipated,” says Miller.

“Well-intentioned” but doomed to fail

Miller also highlights the recent push by Australia’s peak union body, the Australian Council of Trade Unions, for a 7% wage rise via the Fair Work Commission’s annual wage review.

“That is a worrying portent of future inflation. An indication from the Government that it would support an increase in the minimum wage in line with inflation (or something close to it) in its submission to the FWC's review is also a concern,” he says.

“While well-intentioned, such a move may simply spur inflation pressures as it ripples through the award system and beyond, at a time when productivity has been going backwards.”

He also believes such actions will not achieve the stated aims of lifting the living standards of low-paid workers. That's because any gains would be more than offset by higher living costs (or higher unemployment.

“It is also a development that should worry an inflation-focused RBA,” Miller says.

A global perspective – Australia v Europe v US v Canada

Miller also compares and contrasts Australia’s economic situation with that of Europe and the US – where central banks lifted interest rates in March. This was partly in response to the financial system concerns raised by the high-profile collapse of several banks, most recently including Credit Suisse (which was bailed out by a government-orchestrated deal with UBS).

“The RBA also needs to weigh up the implications of any upheaval in the global financial system. But unlike Europe and the United States, Australia is at the periphery of the ripples emanating from that upheaval,” says Miller.

He also makes the point that Australian inflation remains lower than in North America “and even New Zealand.”

“That is, at least in part, because of a less aggressive approach to policy rate increases. That can be perceived as the RBA exhibiting some prevarication in confronting the inflation challenge,” he says.

“Even given the grudging progress on inflation in the US, it is some way down from the peak around the middle of last year,” says Miller.

And he notes the difference is even starker when comparing Canada’s 4.8% trimmed-mean inflation figure with Australia’s most recent quarterly read of 6.9% from December. Miller suggests this figure will likely remain above 6.5% when the March quarter number is released on 26 April.

Given the Bank of Canada (BoC) has tightened by 425 basis points, he believes it could “credibly pause” when it next meets because the central bank has been among the most aggressive movers on rates among the developed world.

“There is not yet any meaningful turning point evident in the Australian quarterly CPI data,” says Miller.

“As far as the Government’s (understandable) anxiety regarding higher interest rates, it is probably the case that, given the election cycle, it is best to get interest rate rises out of the way more quickly rather than draw them out.

“A premature pause may require the RBA to slam the brakes later in the cycle resulting in an even greater dislocation in activity and employment. That is the lesson to be drawn from the experience of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s.”

He believes that any move to pause on rates now would risk further damaging the RBA’s “already tarnished inflation-fighting credentials.”

“In the past the Governor has mentioned that the path between the vanquishing of inflation and avoiding a recession, or at least a sharp growth slowdown, is a narrow one,” says Miller.

“Were the RBA to avail itself of a pause in the rate hike cycle, when the data dependence criterion has not been met, the Governor’s path could get even narrower.”

THE CASE FOR A PAUSE

James Gerrish, portfolio manager of Market Matters, mentioned the monthly CPI data in his recent commentary, published after Wednesday’s market close.

“Coming in at 6.8% versus the 7.2% that was expected, and down from 7.4% last month, clearly, inflation is cooling,” Gerrish writes.

“And while it is still way too high, it’s heading in the right direction, while today’s result should cement the RBA’s decision to pause in April, the market is actually pricing in no more rate hikes from here.”

Several commentators from a panel surveyed on the RBA cash rate by consumer comparison website Finder also expect the central bank to pause on rates when it next meets.

Among the 16 commentators (38%) who expect the cash rate to be left unchanged on Tuesday are:

Shane Oliver, AMP

"After 10 rate hikes in a row it's time for a pause, the RBA has said it will consider a pause at its next meeting, economic data is showing increasing signs of cooling activity and peaking inflation and banking turmoil has increased the risk of a global recession. So while its a close call on balance we think the RBA will pause in April."

Malcolm Wood, Ord Minnett

"The RBA has tightened too aggressively, driving a domestic downturn. Inflation should turn much lower, allowing 2H23 rate cuts."

Craig Emerson, Emerson Economics

"The RBA would be wise to pause in the face of a possible financial crisis and ensuing recession in the United States and some other advanced economies."

Gareth Aird, Commonwealth Bank

“We now expect the RBA to leave the cash rate on hold at 3.6% at the April Board meeting, in what we believe is a very close call. We ascribe a 55% chance to no change and a 45% probability to a 25bp rate increase to 3.85%.”

Leanne Pilkington, Laing+Simmons

"The minutes from the March meeting indicate the RBA is considering pausing the rate rise cycle and we believe this would be the right move. People need a reprieve and in the housing market, buyers and vendors need to know where they stand with a degree of certainty."

Mathew Tiller, LJ Hooker Group

"The lag between when the RBA increases rates and their full effect on the economy, signs that inflation has started to soften, uncertainty around the outlook for the global economy (including US banking issues) should all be enough reasons for the RBA to pause, take stock and evaluate the impact of the past ten consecutive rate hikes on the economy."

Peter Munckton, Bank of Queensland

"The RBA will keep rates unchanged in April reflecting the increased uncertainty in financial markets. It will also allow them to assess the impact of the rate hikes to date."

3 topics

2 contributors mentioned