“Time migration of expectations” as a signal of central bank policy failure

Interest rate parity is one of the core propositions in finance holding that offshore and domestic interest rates are equalised after the impact from currency hedging is taken into account. Yet over a 15 year period from 2002-2017 domestic investors were able to earn materially higher relative returns from investing in global bonds partly due to the outsized returns available from currency hedging. That such returns from currency hedging should be available appears to violate the basic tenants of interest rate parity. However once account is taken of the potential impact from the ‘time migration of expectations’ arising from ‘policy failure’ the anomaly becomes easier to understand and explain.

What is interest rate parity?

Interest Rate Parity (‘IRP’) is a key financial relationship and has very important implications when considering the impact of currency hedging on the returns earned from holding global fixed income securities. In terms of currency hedging the key underlying hypothesis can be illustrated by assuming :

(a) underlying bonds are held to maturity so there is no ‘realised’ change in bond valuations

(b) term to maturity (“TTM”) on currency hedge equals TTM on underlying bond

Under these assumptions IRP results in Yield to Maturity (“YTM”) equivalence. Equivalence arises as in effect :

YTM Bond Global AUD = YTM Bond Global Global + YTM Currency Hedge

which becomes :

YTM Global Bond AUD = YTM Australian Bond AUD

as :

Currency Hedge Return = YTM Australian Bond AUD – YTM Bond Global Global

In reality the picture is a bit more complicated as investors in long global bonds do not take out long dated currency hedges; i.e. there is a TTM mismatch between the currency hedge and the long bond. Due to the TTM mismatch the returns on the Global Bond AUD will diverge from that of the Australian Bond AUD where there is a difference in the shape of the yield curves.

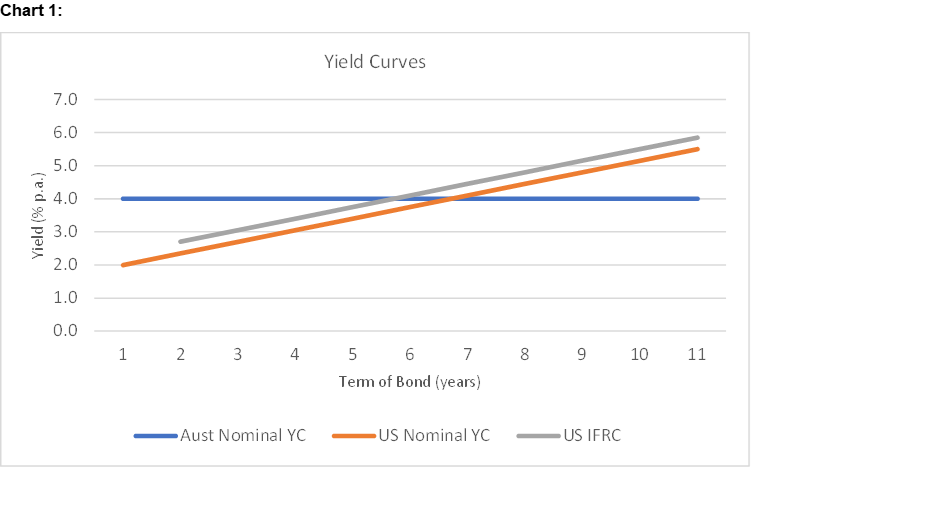

Driving the difference in returns is that shorter term currency hedges are expected to be priced according to the Implied Forward Rate meaning that over time the hedges roll along the implied forward rate curve (“IFRC”)[i]. Such a situation is shown in Chart 1 where an upward sloping global, or US, YC is compared to a flat Australian YC. In the scenario the US IFRC lies above the nominal yield curve while for the Australian yield curve, being perfectly flat, the IFRC and the nominal yield curve are the same.

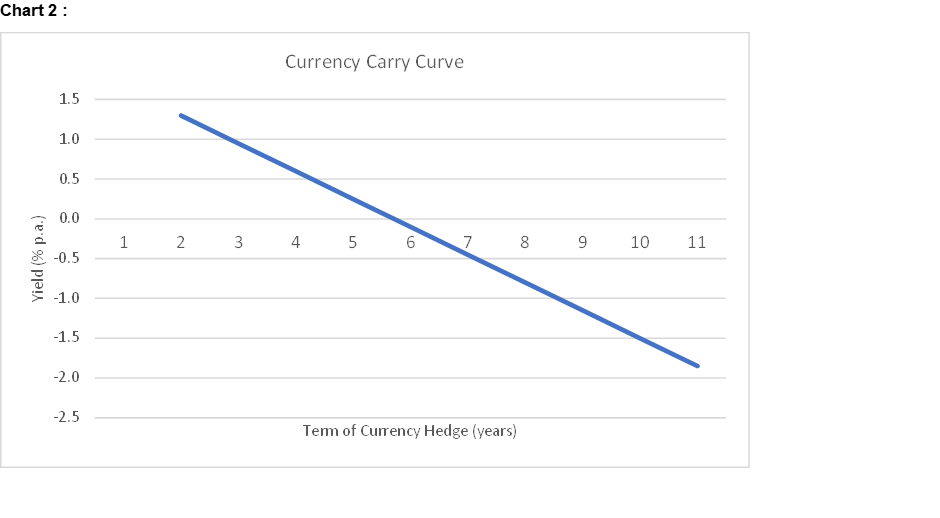

The difference between the two IFRC curves can be considered as the currency carry and ensures equivalence of the hedge bond rate returns. Such a stylised Currency Carry Curve (‘CCC’) is plotted in Chart 2.

The CCC highlights how over the early years currency hedging is expected to earn a positive return for the investor but then eventually turns negative. In theory the result of this process is that even where there is a TTM mismatch between the underlying bond and the currency hedge if a position is held to maturity then again Yield Bond Global AUD = Yield Bond AUD. This equivalence condition implies that all else being equal an investor should be indifferent between buying a domestic bond versus a fully hedged offshore bond. But not all else is equal meaning that there is an important caveat to this statement regarding equalisation. Importantly, the relevance of the IFRC only applies at a point in time. Put another way, the IFRC quantifies the markets expectation at a point in time it does not say that those expectations are constant or will be proven correct as time goes by. It is for this reason that the equivalence proposition may not necessarily hold over shorter intervals.

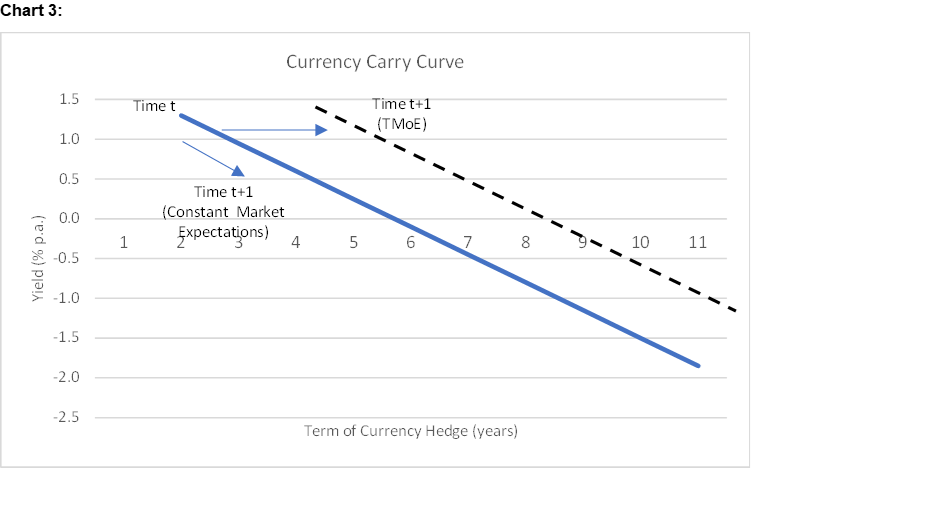

As equivalence only holds if the rollover of the currency hedge occurs along the current CCC, it stands to reason that investors can gain when the CCC shifts. Given this it is now necessary to distinguish between two types of changes in expectations. Firstly, market expectations at a point in time can change regarding the future level of interest rates resulting in the shape of the respective yield curves changing. As such changes in expectations are likely to be largely random in nature; i.e. driven by information flow, they are unlikely to result in systematic biases. The second type of change is where the shape of the YC remains the same but migrates through time. This may be referred to as “time migration of expectations” (‘TMoE’) and can, theoretically at least, create systematic biases over extended time periods.

The significance of TMoE is that it has the potential to create systematic biases within fixed income markets as its behaviour is non-random in nature. When TMoE is impacting markets as time passes rather than moving down the CCC the curve moves to the right. The result is that rather than IRP holding a structural bias is created over time which violates IRP meaning that excess returns can be generated by holding one bond over another.

As this is a fine distinction that is being made between drivers in expectations it is useful to clarify by considering two examples of the same event. Initially assume the market expects that the RBA will raise rates a certain amount beginning in 1 month. The market receives some new information and alters their view to reflect the expectations that interest rates will follow the same path but only now the initial rate rise won’t begin for 2 months. Such a change in expectations alters the profile of interest rates therefore impacting on the shape of the yield curve and hence long bond rates. Now consider another situation. The starting point is the same where the market expects that the RBA will raise rates a certain amount beginning in 1 month. Only now after 1 month nothing has happened, but still being convinced that rates will be increased beginning in 1 month, the market maintains the same interest rate profile. The importance is that now the expectations are being pushed out but the profile of interest rates and hence their levels remain unchanged. In effect expectations are migrating through time as opposed to changing over time. The differential between longer dated securities remains the same meaning that the higher short term differential is earned for a longer period of time. This is analogous to the CCC moving to the right; i.e. investors gain on the currency hedge, as opposed to changing shape. Chart 3 aims to illustrate the situation where market expectations are maintained regarding the future path of interest rates, they just migrate over time. TMoE impacts mean that, rather than rolling hedges down the CCC, the CCC moves to the right resulting in the failure of the market to equalise returns between domestic and global bonds even though the yield differential on longer dated securities hasn’t changed.

But be aware that this is not a market anomaly which can be arbitraged. The market is accurately pricing the yield curve versus expectations at any point in time hence the market is efficient. An investor can only profit from this phenomenon by accurately predicting that the YC will shift or change in shape over time. Accordingly, the excessive return on the CCC will generally only be evident after the fact.

TMoE as a signal of ‘policy failure’

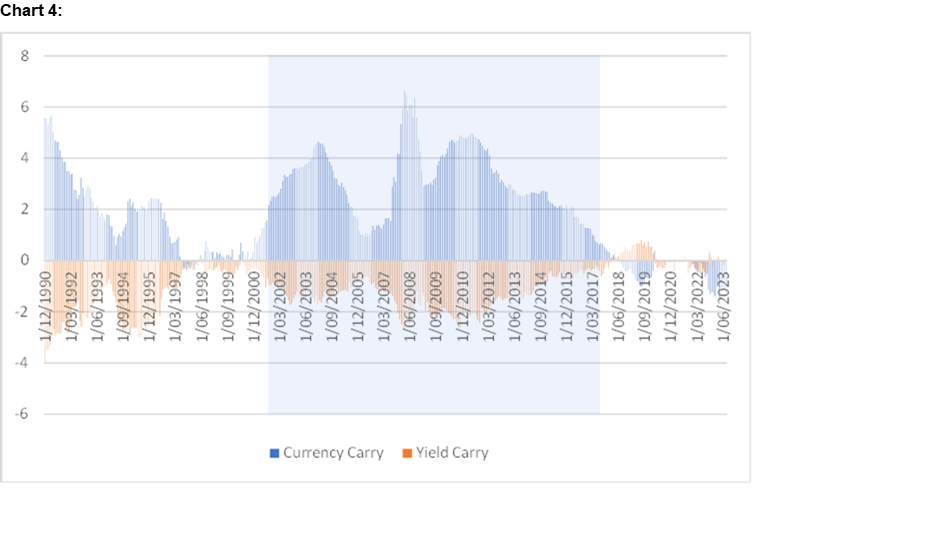

It is one thing to refer to a phenomena at a theoretical level it is another to identify a practical impact. To identify whether this is a practical issue it is worth considering US and Australian interest rates since the 1990’s. To identify the main impacts interest rates can be broken down into the two components described earlier namely :

Net Carry Global = (Short Rate Aust 3M – Short Rate US 3M) + (Long Rate US 10 Yr – Long Rate Aust 10 Yr)

Where the Net Carry it is the difference between the Currency Carry (differential between short rates) versus what may be viewed as the Yield Carry (difference in long bond rates) [See Chart 4].

Not surprisingly for an Australian investor buying and hedging US Treasuries, as Australian interest rates have tended to be higher than US interest rates, the currency carry has a bias to be positive while the yield carry is biased to be negative. What stands out is the differences in behaviour over sub periods. From the periods 1990-2001 and 2017-2023 the Currency Carry and Yield Carry largely offset each other resulting in the net carry being quite small. The existence of small differences (around +/-20 bps p.a.) is entirely consistent with IRP holding once allowance is made for the simplifying assumptions made to decompose yields. By contrast during the period from 2002-2017 the Currency Carry was materially higher than the Yield Carry for an extended period of time (averaging around +180 bps p.a.).

The existence of a material distortion to the Currency Carry points to the potential that there has been a ‘policy failure’. What is meant by ‘policy failure’ in this sense is where central banks have kept interest rates at levels which the market does not view as being sustainable. As the Currency Carry is determined by a differential between two rates the difficulty becomes determining which of the central banks is generating the policy failure. Taking the experience of the post 2000 period it is reasonably safe to conclude that the more likely source of policy failure is the US Federal Reserve. Specifically, relative to the Reserve Bank of Australia, the US Federal Reserve appears to have kept the level of US short term interest rates persistently lower than justified by the market expectations built into the longer bond differential. The result was that Australian investors in US Treasuries would have earned an outsized positive return from the Currency Carry associated with hedging back into AUD. This points to the potential that TMoE was distorting market dynamics over an extended period of time; i.e. the relative convergence in cash rates implied in the longer dated bond rates was not occurring. With US short term interest rates remaining lower versus Australian rates than the market was expecting the equalisation of bond yields implied by IRP was prevented. This may in turn point to a ‘policy failure’ by the US Federal Reserve as monetary policy was kept more accommodative than it should have been in the period post 2000; i.e. policy settings were kept at levels the market viewed as unsustainable over the longer term.

There are a range of factors which can act to create distortions in the equivalence of global and domestic bond returns implied by IRP. One dynamic driving the distortions is the potential for the ‘time migration of expectations’. TMoE can result in the Currency Carry being distorted systematically over extended periods of time. Though it is difficult to predict beforehand when TMoE will occur it is reasonable to assume that it is more likely to be associated with periods of, what may be referred to as, central bank ‘policy failure’. During these periods central banks are likely to be maintaining policy settings at levels which the market does not view as being sustainable over the longer term. The resulting disconnect between central bank policy and market expectations may result in TMoE occurring over a sustained period and distorting the dynamics normally associated with interest rate parity.

[i] The concepts around Implied Forward Rates has been dealt with in an earlier Livewire article entitled “Is time money? Long-term bonds vs long-term exposure what really matters?” which readers can reference for a more detailed explanation.

3 topics

Clive Smith is an investment professional with over 35 years experience at a senior level across domestic and global public and private fixed income markets. Clive holds a Bachelor of Economics, Master of Economics and Master of Applied Finance...

Expertise

Clive Smith is an investment professional with over 35 years experience at a senior level across domestic and global public and private fixed income markets. Clive holds a Bachelor of Economics, Master of Economics and Master of Applied Finance...