Titanic economic forces are clashing, and uncertainty is increasing

I have some pretty clear ideas about which trends are sustainable and which ones aren't in the long term. However, the short term is far less clear. A combination of the Omicron variant and a geopolitical energy crisis in Europe have extended inflationary and supply chain issues. The net effect? Titanic economic forces are clashing, and macroeconomic uncertainty is high. The odds of a policy error looms over everything. And so, your investments need to reflect that.

From a stock selection perspective, that means pulling back on both our sector overweights, and our underweights. It is not the time for intransigence; it is the time to be open to unfolding events. But not as bi-polar as the stock market - you could get whiplash trying to follow the risk-on/risk-off trades day to day and even hour to hour. It is about positioning the portfolio towards the most likely outcome and gradually increasing the weights as more data arrives.

For asset allocation, it means keeping our hand close to the rip-cord. Omicron likely heralds the end of the pandemic. Given the extreme transmissibility, most countries will have peaked before the end of February. The initial stock market reaction will likely be up. The shadow of policy error will loom over this rise - we will probably be selling into rallies.

Titanic Forces

Some of the forces we are focussing on:

- Demand changes - which are permanent and which are transitory

- Supply changes - increased focus and ingenuity trade blows with lockdowns and gridlock

- Energy geopolitics - Europe vs Russia, ESG vs fossil fuels, China vs itself

- Chinese slowdown - will it stimulate property or not

- Government fiscal pullback vs extraordinary investments already made

- Labour markets - I quit! Lifestyle vs increased wages

- Monetary policy - will the Feb make a mistake?

Inflation is in some way another force, but mostly inflation is an outcome of all of the above.

Demand Forces

Since the pandemic began, we have been living in a new world for demand.

US Goods vs Services

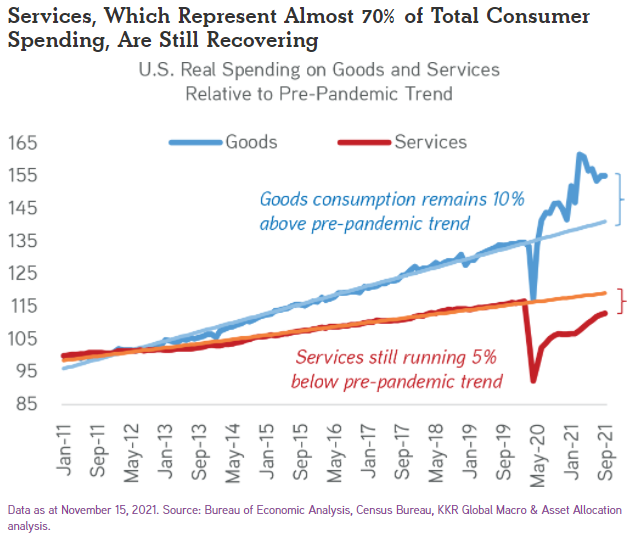

Goods consumption in the US boomed and remains well above prior trends:

One trope is people stuck at home spend more on goods because they can't spend on services. When the pandemic ends, will this revert to usual? Some people will stay cautious. Some can't wait to get out and travel again. Which force will be stronger? Will it take six months to return to normality? Six years? Will there be new variants sending people back into hiding?

In the long term, more services and fewer goods are likely. But the current situation could persist for some time.

International Goods demand

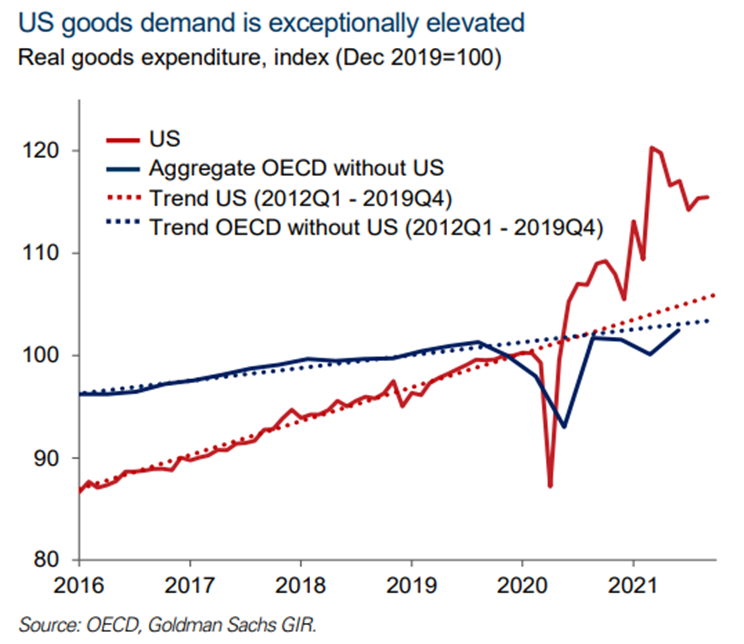

The demand trends we are seeing in the US are not true elsewhere.

It is hard to see how coming out of the current virus wave would spur more goods purchases over services. But will goods demand hold up outside of the US, cushioning the impact of falling US demand? Or will it also fall, doubling the downside?

Structural living changes

COVID has sparked a range of different structural changes to the way people live. Quite possibly, some of these will be long lasting.

New household formation is high. This is due to a mix of a range of factors:

- Higher divorce rate.

- I'm guessing the separation of non-married partners is also high.

- And non-partnered living relationships are likely similar. People have seen more of their housemates than they wanted.

- Wanting to live with fewer people to limit quarantines.

- Needing extra space for home office/s.

Household growth can be a big demand driver, more home building, more new furniture etc. This is probably a trend set to stay for several years.

Regional living. Those looking for a sea-change or to take advantage of their new-found ability to work from home put extra demand on housing stock in regional areas. Long term, regional areas can expand supply more readily than metro areas. Short term, supply is an issue. And a building boom.

Houses vs apartments. The desire for a backyard has grown. Which means more building. And probably more rooms to fill with furniture.

A clash of mantras

From one cohort, life is too short. Borrow what you need to and spend, increasing demand.

From a different cohort, life is not about material items. They want to work less, spend more time with friends and family. These people will have less money which means decreased demand.

I'm expecting the first will overwhelm the second while interest rates remain at rock bottom. But I'm not so sure that it will continue to be the case once interest rates rise.

Inequality eases

Lower-income households are more likely to spend additional money, higher-income to save. Over the past few decades, increasing inequality has dampened demand and led to falling inflation.

Inequality measured by assets continues to get worse. Measured by income, there has been some relief. Wage growth has been strongest at the bottom end.

Maybe the wage growth is "frictional". Say you are a waiter. You lose your job at the start of the pandemic, and so you look for other jobs as a waiter. Amazon is looking for people to stack shelves, but it takes a while (and maybe Amazon need to increase wages) before you start looking at different industries and take a job. Then, restaurants re-open, needing to hire back staff. But you have already moved on; they need to increase wages to get you back.

Frictional issues would point to another few years of low-end wage growth. Which is excellent for increasing demand.

On the other hand, maybe some wage increases are "danger money". i.e. if you are going to work somewhere that can send you home without pay with almost no notice, you will want a higher salary. Which is more of a one-off effect, which may even reverse once the pandemic end.

Or maybe it is just that many people have health or childminding duties increased by the pandemic. Or, maybe there was simply too much government support, so people didn't need to work. To incentivise both groups, higher wages are required. But, the end of the pandemic could reverse that trend.

If so, the wage growth at the lower end is limited and short term. This means demand returns to the weak conditions of the decade prior.

Inventory changes

Have the supply chain disruptions meant that "just in time" inventories are no more? If so, there is a boost to demand as companies order more in the short term to overstock inventories.

But maybe that has already happened. The extra goods have been ordered. Due to delivery constraints, the inventory is strung out across the world in ports, ships and warehouses, waiting to be delivered.

Long term, demand will decrease. Short term is hard to tell.

Supply Forces

Supply forces are the more contentious. Many claim the problems are intractable and will last for years. Others suggest the changes are a very short term phenomenon - a traffic jam that will clear.

Some sectors do have structural issues; others merely have supply chain issues. Which will have more effect?

Automation has increased. Driverless vehicles, automated checkouts and robots have a higher tolerance of viruses than human companions. And robotic productivity tends to improve every year. The pandemic has inspired considerable automation, in many cases removing entrenched processes that would have otherwise taken years to resolve. Supply chains will be more efficient once the pandemic ends.

Logistics has struggled. Shipping costs are much higher, and there are delivery delays. There are three main possibilities:

- Demand will revert, and shipping costs likewise.

- Supply will expand, shipping costs will return to historical levels.

- The problem will not be solved for years.

In my view, the odds of the first two far exceed the third option. Also, necessity has driven a thousand minor productivity improvements to the shipping process to speed up issues. We can't see these improvements yet due to the mix of staff lost to quarantine and the traffic jam. But once those factors fade, shipping will likely be more efficient.

Onshoring and shorter supply chains. Many countries and companies have expressed a desire for shorter supply chains to combat the problems the pandemic has caused. Will this actually happen? A local supplier with limited production will likely be higher cost than a company in China producing 100 times more per week.

Post-pandemic, will local producers go out of business? Or will automation bridge the gap? Or will government subsidies/tariffs keep the local producer going? The first two will be deflationary. The third, inflationary. Countries, markets will choose differently. The net effect will not be known for years.

China targetting zero COVID. If this continues, and even if it doesn't, we can expect rolling shutdowns, supply chain interruptions and port delays. Further muddying the waters in the short term for the inflation debate.

Inventory super-cycle

The basis of most business cycles has an inventory cycle at the core. The stocking and de-stocking cycles are what typically drive economies both into recession and out of recession.

The basis of most business cycles has an inventory cycle at the core. The stocking and de-stocking cycles are what typically drive economies both into recession and out of recession.

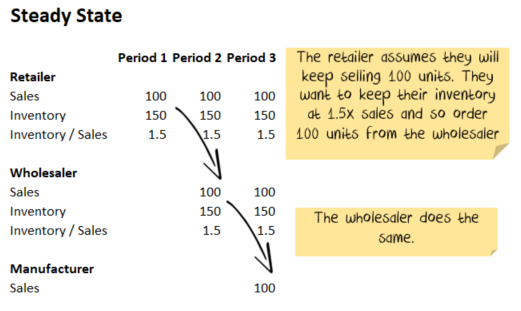

I’m going to start with a grossly simplified illustration. Assume we have:

- a retailer who buys from a wholesaler

- a wholesaler who buys from a manufacturer.

We are looking at the changes from period to period. For some companies, the periods are days. For others, the periods are weeks, months or quarters. Both the retailer and the wholesaler target 1.5x the current period’s sales as inventory.

It looks like this:

.png)

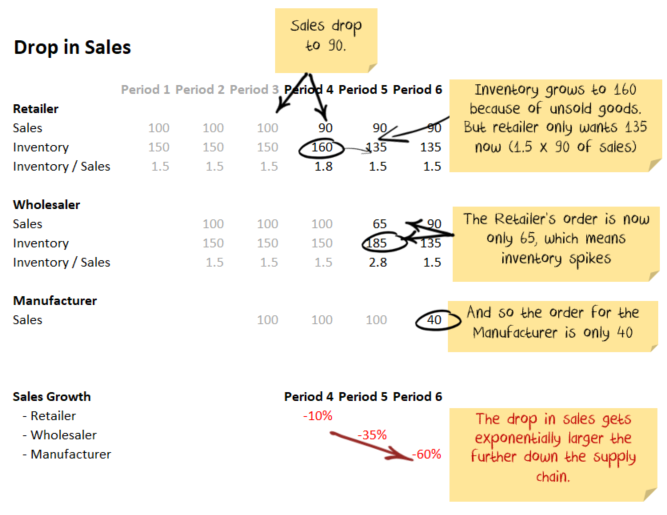

Now let us look at the effect of a drop in demand. Say sales drop 10% for the retailer and then stay at the new level:

.png)

As you can see, the effect is more significant the further down the supply chain you go. A 10% fall in sales for the retailer is a 60% fall for the manufacturer. In the initial stages of a recession, this effect worsens the cycle as manufacturers then fire staff/pull back spending.

But, it works in the other direction as well. When the cycle turns, the opposite effect kicks in.

The issue at the moment is whether short term demand spikes result in significant supply increases. Then, when the demand disappears, suppliers cut prices to get rid of supply. We expect that the extra demand due to the inventory cycle has already increased supply. In the long term, this will be deflationary - too much supply for not enough demand. In the short term, Omicron is playing havoc with the inventory cycle. Lack of supply, hoarding and over-ordering is likely.

Government Intervention

Government intervention was front-loaded globally after the pandemic struck. Governments transferred extraordinary amounts of money to both individuals and companies. Now the tide is going out; governments are pulling back on spending. Will the built-up consumer savings be spent? Or will the decrease in government spending put a dent in demand? Long term, the latter is more likely.

Build Back Better, a large stimulus plan in the US, seems doomed. Individual elements will return, but the overall package will not be as significant. Government support is fading.

Governments also made changes to reduce the likelihood of defaults and bankruptcies through the pandemic. Many of these rule changes are rolling off, but the number of insolvencies is still very low. Will there be a "catchup" and elevated bankruptcies? Or was there so much stimulus that we will just see a gradual return to trend? I was expecting a catchup in 2020. But I changed my mind. I think a catalyst is going to be needed. Probably in the form of interest rate policy error. And I'm still mystified why a reversion to trend is not already underway.

Energy geopolitics

Energy prices skyrocketed in the second half of 2021, particularly in Europe. In my view, a dozen minor factors are contributing, and one major factor.

The major factor is Russia. Having built the Nordstream 2, which bypasses Poland and the Ukraine, Russia is maneuvering to ensure its position and have probably overplayed their hand:

By illustrating the extent to which Russia will manipulate supply, Europe is likely to increase the pace of developing alternative sources like LNG and renewables. But it does create a short term issue.

Minor factors also enter the picture, wind conditions in the North Sea, nuclear policy in Germany, unrest in Kazakstan, temperature variations and supply chain issues potentially creating additional problems.

China also saw energy price rises during 2021. These were influenced by European issues and the industrial production boom. In response, China slowed production in a range of industries, expanded coal production, banned cryptocurrency mining and resumed imports from Australia. To date, these appear to have been somewhat successful - price spikes in Europe later in the year largely failed to see a similar response in China.

Long term, gas and coal prices are headed lower. Short term, energy prices could easily go much higher. Price increases will dampen non-energy demand, acting as a tax on consumers and corporates.

Chinese slowdown

The short version is:

- China has resorted to a debt-fuelled building boom every time it has slowed down in the last 20 years.

- The construction sector has become bloated, outsized compared to the rest of the Chinese economy. Take listed property developers. Chinese developers are larger than the rest of the world combined.

- This is the fourth instalment of Chinese attempts to rid itself of its troublesome property development sector. The first began in 2011. It was ramped up again in 2015 and 2019. The failing growth that followed has spooked policymakers into more stimulus each time.

- China keeps returning to this program for one reason. Its property market excesses are the key threat to its economic development path. Property is both the source of its enduring growth and its doom if allowed to run too far. No other Chinese sector misallocates capital and kills productivity on such a massive scale.

- China has been using the global goods boom, which has inflated industrial demand, to try again.

Three months ago, I expected China would eventually restimulate, but not before a significant downturn in building. At least on the scale that we saw in 2015.

However, Omicron complicates the matter considerably. The economic growth problems Omicron creates increase the odds that China will kick the can yet again.

If China doesn't stimulate, it is negative for non-energy commodities. Investors in commodities seem to already be pricing in China capitulating. Which creates downside risks to commodity prices if China doesn't. The entire complex is dependent on the decisions of a handful of officials.

Long term, the path is clearly down. But there could easily be a short term boom.

Labour

Two segments are clashing:

- The high quit rates and difficulty finding staff reflect: skills shortages, health concerns, and increased early retirement. Higher wages will be needed to resolve the problem.

- Workers have decided that lifestyle is more important than higher wages. Company won't let you work from home as much as you want? Quit and find one that will. Under this scenario, higher salaries won't fix the problem - companies may just need to hire more staff to do the same job. If this is the case, productivity, wage growth and consumer demand will be lower.

Both may be true in different industries. An oil engineer might leave for a desk job near the beach and a pay cut. But to replace them, the oil company may need to cough up a higher salary.

Inflation

All of the above are forces buffeting inflation. To simplify, there are effectively four likely outcomes:

- Demand stays strong. Supply can't expand fast enough: Inflationary

- Demand stays strong. Supply expands to meet strong demand levels: Moderate Inflation

- Demand returns to trend. Supply can't expand fast enough: Disinflationary

- Demand returns to trend. Supply expands to meet strong demand levels: Deflation

For me, the longer-term forces are arrayed for disinflation with a reasonable chance of deflation.

Never miss an insight

Enjoy this wire? Hit the ‘like’ button to let us know. Stay up to date with my content by hitting the ‘follow’ button below and you’ll be notified every time I post a wire.

Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

5 topics