Unintended Consequences of Free Money

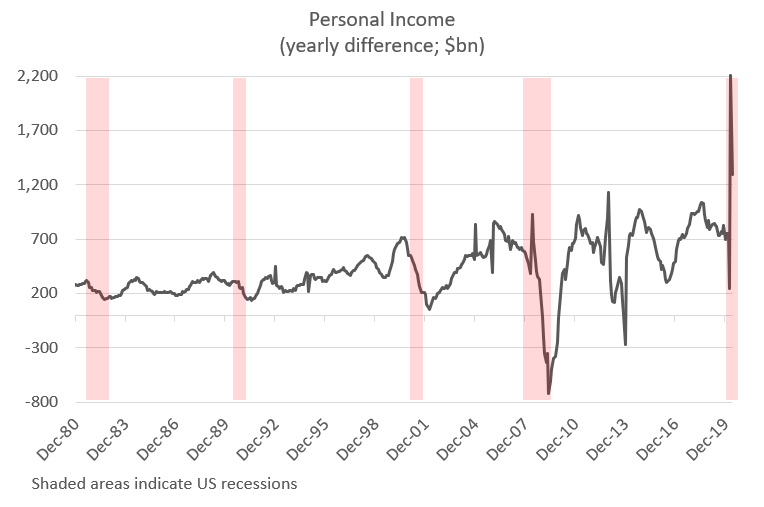

During past recessions, people become poorer as personal income falls when unemployment rises, which intuitively makes sense. However, using the United States as an example, the current recession has seen an anomaly where personal income surged despite unemployment rising.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data

The increase in personal income was significantly influenced by the US Government sending generous stimulus cheques of $1,200 to 159 million households. Further, an extra weekly benefit of $600 was granted on top of the average weekly unemployment benefit of $378 a week. Perversely, some individuals earned more money unemployed than when they had a job.

The combination of cash injections and limited areas to spend during the lockdown meant that some excess cash has found its way into financial markets. While a nascent economic recovery is underway the speed at which stock markets have recovered has been partially fuelled by speculative activity. However, there's unintended consequences of free money.

The speculative frenzy is best epitomised by Robinhood, a zero-commission brokerage platform that’s popular with millennials. Their growth has taken the industry by storm and over the last year they added 3 million accounts. Importantly, half of new Robinhood customers this year were first-time investors.

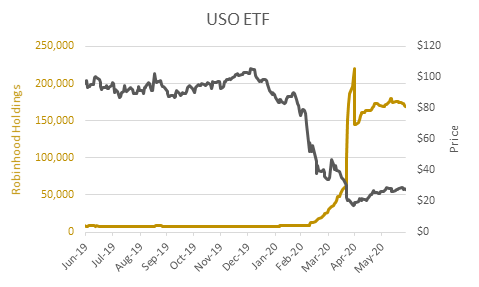

When money is treated like it’s free, the foundation is set for abnormal and volatile outcomes. For example, when the oil price was collapsing in March and April, small investors rushed into the world’s largest oil ETF (USO) not fully comprehending that the ETF invests in oil futures. The large influx of ETF flows was occurring when oil storage was approaching maximum capacity. So, when the ETF rolled its futures contracts (sell the front month contracts and buy contracts further out in the future) it inadvertently forced the price of the May oil futures contract to become negative! Nobody would have thought a negative oil futures price was possible before the COVID crisis.

Source: Robintrack

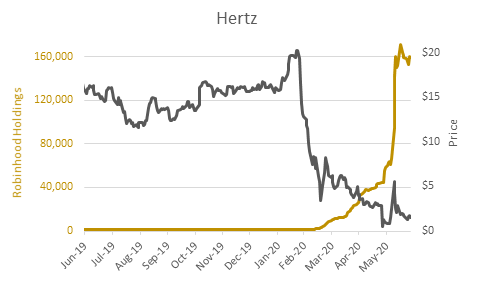

Another bizarre story is Hertz. After being declared bankrupt, the company seized on a wave of speculative interest by issuing $1 billion in equity after its share price surged from its lows. The equity raising (let alone the share price spike) appears illogical given its bond holders are expected to take a big haircut on their $19 billion worth of debt. If the enterprise value of the business is worth less than $19 billion, then the equity raising is a direct transfer of funds from equity holders to debt holders and the equity value is still worth zero.

Source: Robintrack

However, for lucky speculators who bought Hertz stock at the absolute low of $0.55 (26 May) and then sold when the share price peaked at $5.53 (8 June) the trade would have netted a cool 905% return in just 13 days. The share price has since fallen to around $1.50. But never mind that because Robinhood’s client holdings continue to surge as the share price retreated. It looks like the next bunch of speculators are hoping for another lottery ticket win before the company delists.

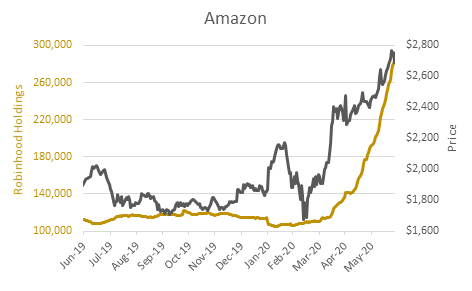

Not only do Robinhooders fish for bombed out stocks, they also chase hot stocks as well. For example, the number of Robinhood’s client holdings in the market darling, Amazon, has nearly tripled since March. It’s as though Amazon, a trillion-dollar market capitalisation company, was an undiscovered gem prior to the COVID crisis.

Source: Robintrack

Australian Experience

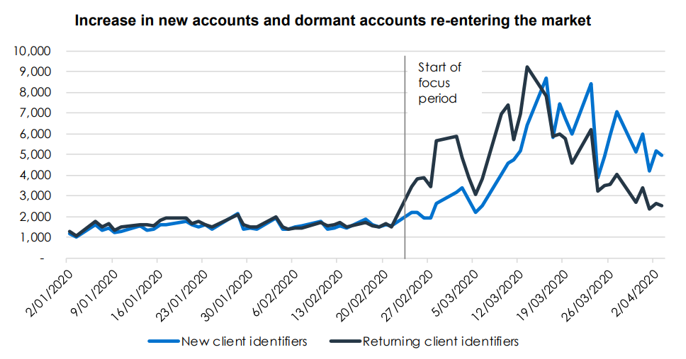

In Australia, there were no free stimulus cheques sent out by the Government. However, the JobKeeper wage subsidy of $750 a week resulted in some low wage Australians potentially making more money than they did before the COVID crisis. Further, zero commission stock trading is still in its infancy in Australia. However, like the Robinhood effect, Australian retail broking accounts increased during the crisis.

Source: Retail investor trading during COVID-19 volatility, ASIC, May 2019

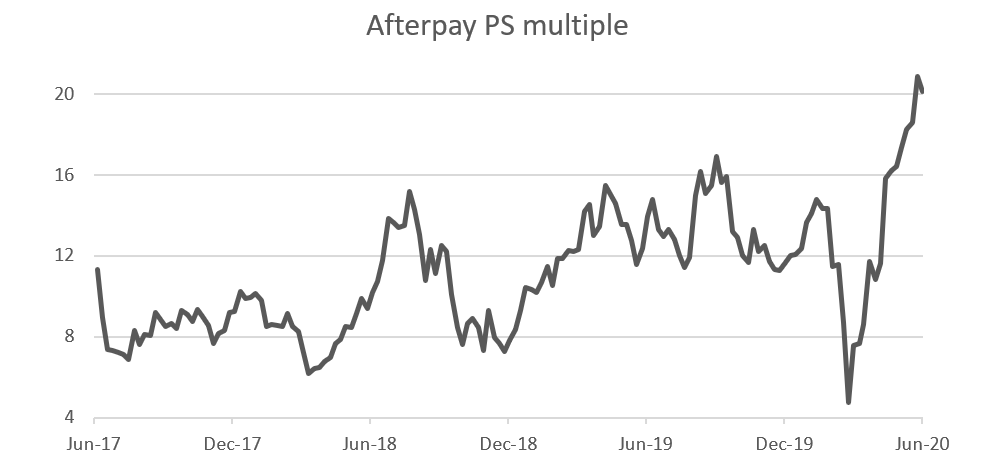

Another indirect sign of speculation can be observed through the lens of valuations. For example, Australia’s leading Fintech, Afterpay (APT), has performed spectacularly well since the crisis. APT is now the 22nd largest company listed on the ASX.

Given that APT still makes losses, shareholders often justify its rich valuation based on price to sales (PS) multiples. At the depth of the crisis it could be argued that APT looked cheap versus its historical PS range when its share price collapsed 78% from peak to trough. However, after its spectacular rally its PS multiple imply that the company’s prospects are 40% better than in February. Have the fundamentals improved that much or has speculation driven a portion of its rally?

Source: FactSet

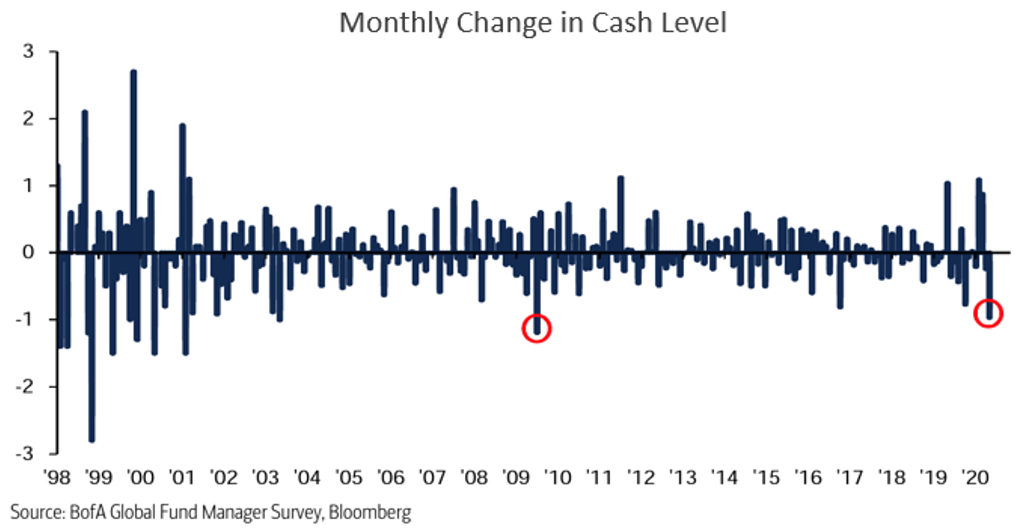

While small investors were quick to capitalise on depressed valuations since March, institutional investors have largely stood on the sideline for much of the stock market rally until recently. The latest BofA global fund manager survey highlights that institutional investors suffered a bit of FOMO. Fund manager cash levels just recorded their biggest monthly drop since August 2009 (six months after the S&P500 rallied 43% from its GFC lows).

Conclusion

Governments and Central Banks have collectively become the modern day Robinhood. But this time, instead of taking it from the rich they are printing free money. In a world of free money, speculation can spawn perplexing and volatile outcomes.

While there is a grain of truth for an economic recovery it is coinciding with rampant speculation. With so many speculators or FOMO investors on one side of the boat it would not take much to tip it over. With market valuations on knifes edge would a bit of bad news create a tipping point?

Get investment insights from industry leaders

Liked this wire? Hit the follow button below to get notified every time I post a wire. Not a Livewire Member? Sign up for free today to get inside access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

2 topics

1 stock mentioned