Want to make better forecasts? Here are two traps to avoid

“We have two classes of forecasters: Those who don’t know – and those who don’t know they don’t know” – John Kenneth Galbraith.

The problem with precision

Most forecasts begin with a starting point which is often anchored to current data. Forecasters tend to modestly extrapolate up or down from this level. This tendency to stick close to current conditions, or consensus views, limits a forecaster’s ability to comprehend the full range of possibilities or the impacts of more extreme circumstances.

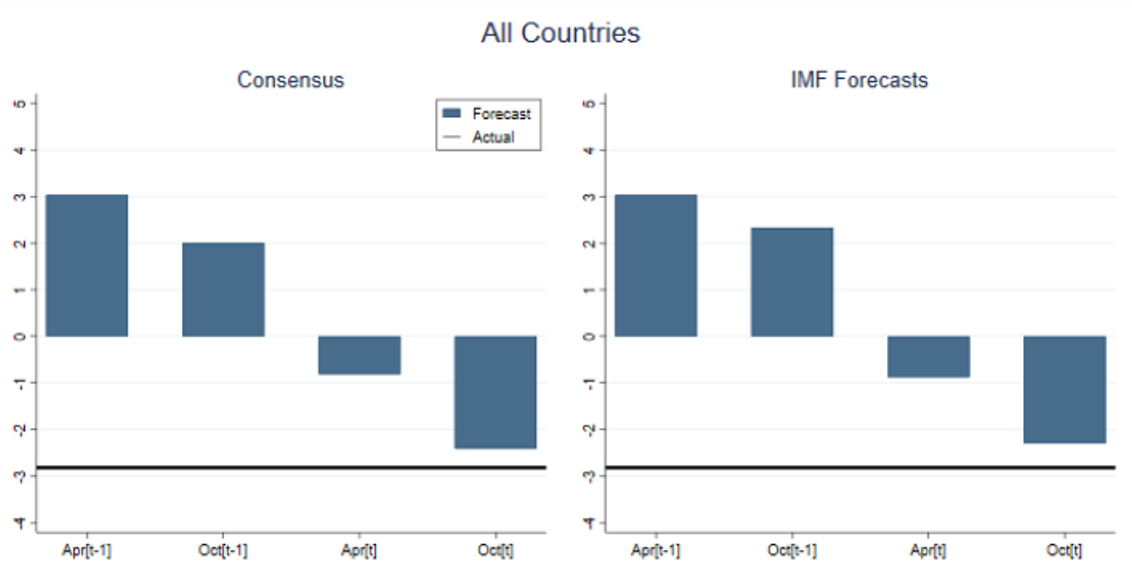

Research by the International Monetary Fund explored the ability of economists to predict recessions between 1992 to 2014. It was a disaster. Economists consistently failed to predict a recession in GDP by a significant margin. Even as conditions deteriorated, economists stubbornly anchored their forecasts to the preceding non-recessionary period and adjusted their predictions downwards too little, too late.

Figure 1: Evolution of Economist Forecasts in the Run-up to Recessions 1992-2014

Source: “How Well do Economists Forecast Recessions?” An, Jalles, Loungani 2018

Moreover, investment success is not dependent on the preciseness of predictions but instead the variance from the consensus. Equities generally price in the risks and opportunities that the market is aware of. It is often unforeseen events that have dire consequences or large rewards.

The real trick of contrarian value investing is to invest when market pessimism already prices in the direst scenario such that it is still a reasonable investment even if this comes to pass and a fantastic one should the situation improve.

A case study – Oil Search

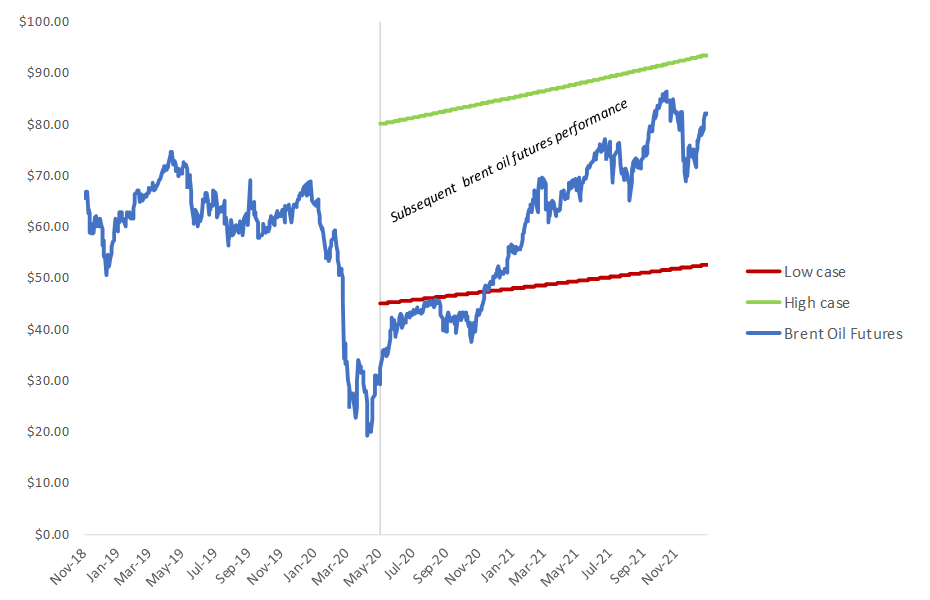

In May 2020, in the midst of COVID-19’s first wave, we initiated a position in Oil Search (ASX: OSH). This was an extremely volatile time for investors with the everchanging circumstances from the spread of COVID-19 without knowledge of a successful vaccine. The demand shock from global lockdowns, flights grounded and recessionary conditions sent some oil futures sharply into negative territory before recovering slightly to historically low levels.

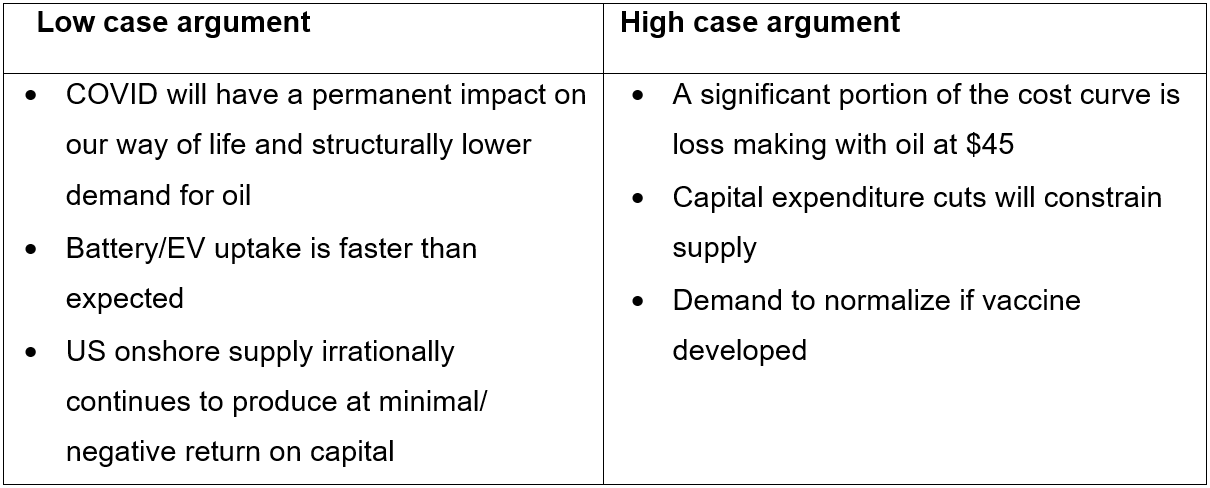

Volatility in oil is not uncommon. In fact, short-dated oil futures historically have a standard deviation of 37%. Mixing in the unknowns of COVID, it became a very difficult proposition to forecast the oil price over the next year and beyond. By considering a range of scenarios, we instead weighed up the supporting evidence for a sensible range of outcomes.

Our fundamental assessment was that supply rationalization and a return to pre-COVID demand was a more likely situation than the alternative, and hence more supportive of the high case argument. Conversely, market estimates were in the range of $40 to $65 /bbl at the time, likely a short-sighted anchoring to recent levels. The Merlon high case of $80 seemed ludicrous by most forecaster’s standards.

Yet, oil futures hit $80 in November of the following year.

Figure 2: WTI Brent Oil Futures and Merlon High/Low range

Source: Bloomberg, Merlon Capital Partners

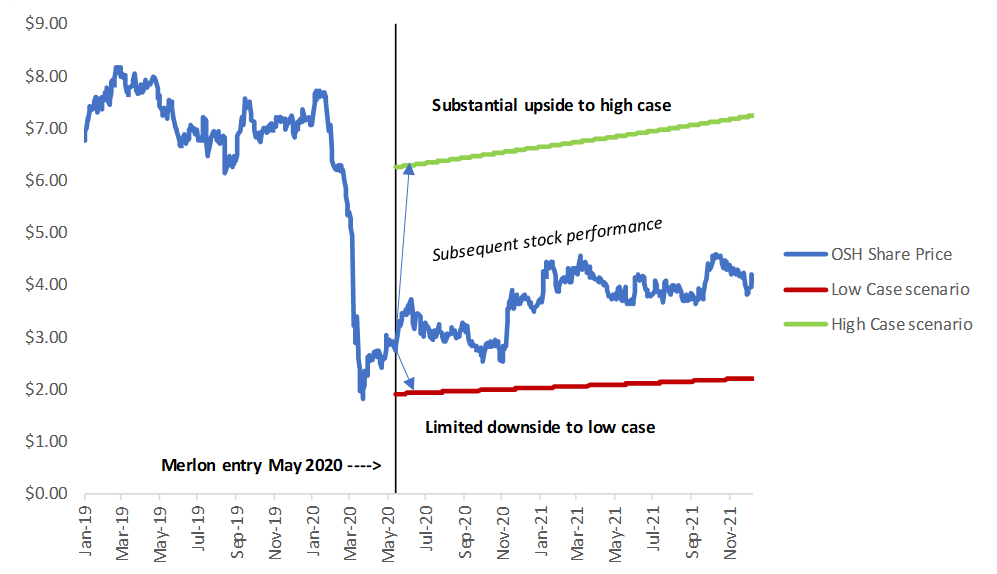

Applying our range of oil price assumptions yielded the valuation sensitivity of Oil Search for our high/low oil price. With substantial upside to the high case compared to a more limited low case downside, this represented a very attractive risk/reward skew. Having a range allowed us to remain acutely aware of the downside risk as the stock price changed and new information came to light.

Figure 3: Oil Search Share Price and Merlon High/Low range

Source: Bloomberg, Merlon Capital Partners

Behavioural pitfalls

Part of our investment philosophy is a healthy scepticism of popular opinion coupled with an awareness of our possible misjudgment and human bias. Here are two biases that we observe to be particularly pervasive in equity markets today and that we are vigilant in avoiding.

1. Recency bias. Recency bias favours recent events over historic ones. Like many living with COVID over the past two years, we commonly hear that certain trends are here to stay: Zoom business meetings, working from home, higher in-home consumption, a shift from urban centres to coastal or regional living. While we consider the possibility some of these may be permanent, we are cautious about extrapolating near-term conditions too far into the future.

Notably, we saw the recency bias play out in the oil market as forecasts anchored too heavily on COVID conditions. There was little allowance in the market for oil prices to rise above $60 which led to the outsized returns when it did (and to the detriment of those who avoided oil).

2. Overconfidence and Narrow ranges. In Nicholas Taleb’s book The Black Swan he highlights a study, where students were asked to estimate “how many Redwoods are in Redwood Park, California?” Students would respond with a range between two numbers in which they were 98% confident the answer fell into.

45% of respondents failed. They had used a range that was too narrow due to overconfidence in their ability. These students were the cream of the crop Harvard MBAs.

Our human inclination is to narrow our ranges as we gain more knowledge. The more “expert” we become, the higher our tendency to overstate our abilities, and in turn our ability to forecast. And our propensity to become arrogant can blind us to risks beyond our ability to incorporate them.

In December 2019, we made public a letter to the Caltex board of directors, alongside our valuation range of $20 to $40 for Caltex, in support of the Alimentation Couche-Tard proposal to acquire Caltex for $38 including the value of franking credits. The board rejected the offer and the chairman noted our valuation range was too wide. Less than three months later the shares traded at $20, triggered by the pandemic, and are currently trading at $30 more than three years later.

The Merlon process

We utilise a broad scope of possibilities when evaluating companies because it is often the improbable and unpredictable events that generate above-market returns. It acts to limit our overconfidence in our central case and reflect on what else might go right or wrong.

1. Range of outcomes. We consider all our stocks in a valuation range between the worst and best case long-run scenarios. This holistic view considers scenarios in addition to our central case, the skew in outcomes and the materiality of payoffs.

2. Long term. We mitigate possible recency bias by observing a long history (usually 10 years) and capturing a spectrum of business performance over time instead of over-emphasising the latest result.

3. Downside protection. We define "risk" as the permanent loss of capital in the long run. We consider “what happens if we are wrong?” and open a discussion on downside risks often dismissed in a precise thesis. This degree of downside is explicitly factored into our level of conviction and portfolio weights.

4. Conviction. Cheap stocks are usually cheap due to valid concerns. We look for an explicit view, contrary to consensus. Has the market narrowed its expectations too finely (see overconfidence, above), thereby dismissing any chance of improbably good news? Alternatively, is it leading us into a value trap by missing meaningful tail risks?

To our clients and prospective clients, it can be difficult to admit that we may not know how the future might unfold. Will COVID be permanent? How will we be using the internet in the future? Will interest rates return to higher, more normal, levels?

In this regard, we are more aligned with John Maynard Keynes’ view that “it is better to be approximately right than precisely wrong”.

Two years into COVID-19 the future is no less clear than when we started. This does not mean we fly blindly but rather undertake deep fundamental research to prepare for the possible outcomes. By factoring in best- and worst-case scenarios and being humbly introspective in our forecasting ability, we strive to tilt the odds in our favour.

Look beyond quality

Merlon's investment approach is to build a portfolio invested in companies with valuation upside on a broadly equal weight basis. For further information please 'contact us' below or visit our website.

1 stock mentioned