What can credit investors learn from the demise of Credit Suisse?

In March 2023, 170 year old investment bank Credit Suisse required a hastily-arranged takeover by UBS to prevent a banking crisis and broader economic fallout in Switzerland and likely other parts of the world.

There are some important lessons for debt investors to take away from the bank’s demise. Three stand out to us:

- Fundamental analysis is critical

- Credit risk is asymmetric

- It’s important to leave your behavioural biases at the door

#1. Fundamental analysis is critical

Central bank stimulus was a boon for investors in the decade or so following the Global Financial Crisis. During this period corporate default rates in the US were only around half their long-term average (1). But now that central banks have ceased their stimulus programs, corporate default rates seem likely to rise back up towards longer-term averages. If that’s the case, it’s important to consider the possible cost of these defaults.

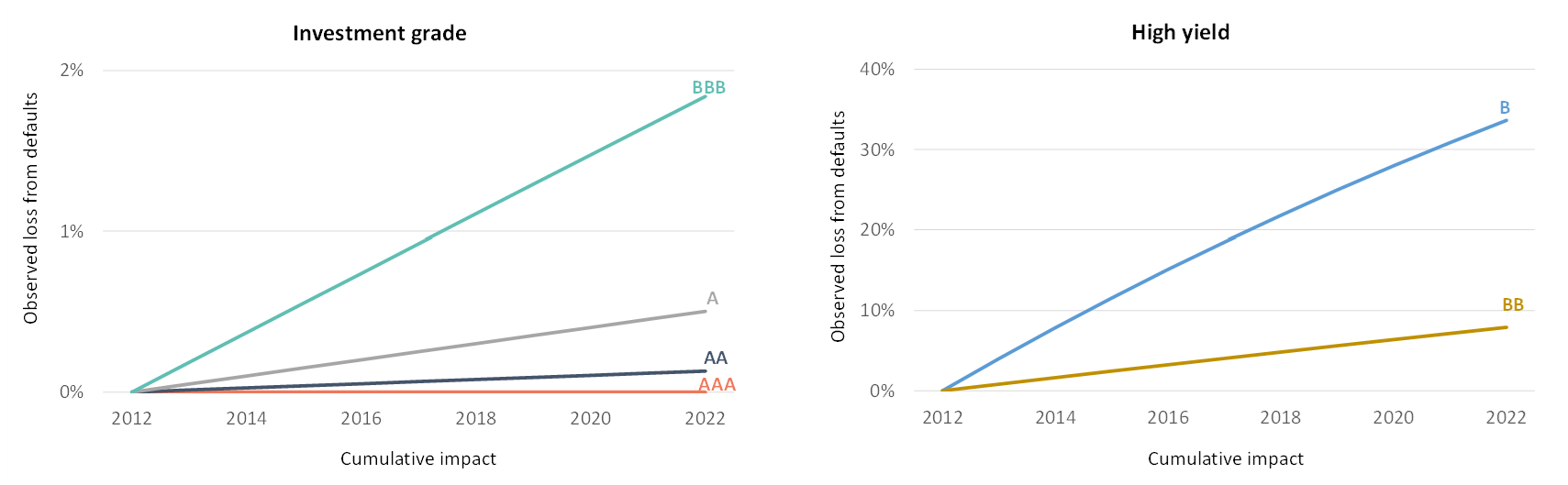

Figure 1 below shows the cumulative return at risk from defaulting issuers in each rating bucket over a 10-year period, assuming long-term default rates. As we can see, if default rates rise back up towards these long-term averages, a passive allocation to credit markets could see investors risk meaningful returns.

Figure 1: The cumulative impact of 10 years of defaults

Source: S&P 2022 Annual Global Corporate Default and Rating Transition Study. The cumulative impact of defaults is shown based on average annual default rates between 1 January 1981 and 31 December 2022.

Thankfully disciplined fundamental analysis can help avoid exposure to these poor investments, helping to preserve capital. This was certainly the case with Credit Suisse.

It was widely understood that the bank was under significant pressure from a fundamental credit perspective. Concerns had been slowly building for a number of years, following numerous litigation and misconduct-related issues. These incidents questioned the bank’s governance practices, culture, risk appetite, and risk control procedures.

It is extremely difficult to predict the exact timing of banking failures, but historically most have occurred following a change in confidence levels that in turn affects a bank’s liquidity. Confidence in Credit Suisse in the lead-up to its failure was steadily fading. Some headline events in the six months prior to the collapse included:

These issues were reflected in our credit risk assessment for Credit Suisse and the different debt securities issued by the bank. As a result, Credit Suisse Tier 1 Capital notes have not been held in our Global Credit portfolios for several years.

Ultimately, over the weekend of 18/19 March 2023, the Swiss National Bank and Swiss Government hastily arranged a takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS, to limit the risk of contagion in the Swiss and likely broader global banking systems and economies. As part of the takeover process, the value of Credit Suisse’s Tier 1 Capital notes – a type of Subordinated debt and also known as Perpetuals or Contingent Capital Securities – were written down to zero (2). Equity holders also walked away with only a few cents in the dollar.

Tier 1 Capital notes are designed to have loss features across every jurisdiction globally, with a numerical trigger level related to capital ratios, to help save banking systems and economies from bank insolvencies. Swiss Tier 1 Capital notes, in particular, contain clauses allowing for loss absorption at the discretion of the regulator. It was therefore unsurprising that investors in the Tier 1 Capital notes were exposed to losses, considering the many failures of Credit Suisse in the period leading up to the bank’s demise.

Lesson 1: It’s critical to read and understand the documentation surrounding each debt security, know the local regulations, and rely on fundamental analysis to assess the risk/reward trade-off to determine investment decisions.

#2. Credit risk is asymmetric

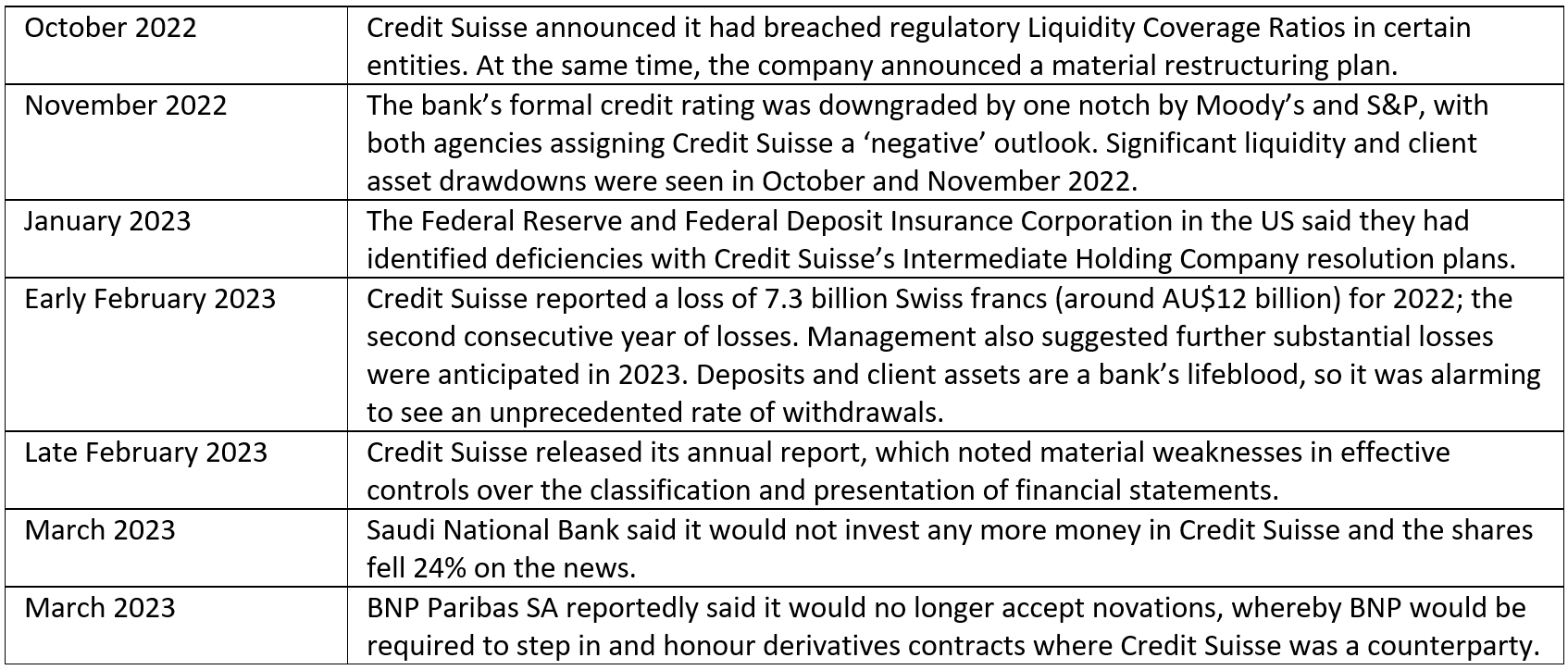

When assessing the risk of debt instruments, investors must first accept that the return profile is asymmetric. Prospective positive returns are limited to the receipt of coupon payments during the life of the bond, as well as the return of the bond principal at maturity or the price obtained by selling the bond in secondary markets prior to maturity. On the other side of the ledger, there is the risk of losing 100% of the purchase price.

Below is a stylistic illustration showing the price probability outcomes for Senior Unsecured bonds and Subordinated instruments (like Tier 1 Capital notes).

Figure 2: Stylised price probability outcomes for different bond types

Source: First Sentier Investors

The higher likelihood of default on Subordinated debt versus Senior Unsecured bonds – as well as significantly larger loss given default expectations – means Subordinated bonds typically trade with higher spreads than Senior Unsecured bonds. Note: in times of stress, one would expect spreads on both types of debt to move higher (and prices fall), indicating rising default risk.

Importantly, due to the embedded loss features of bank Subordinated debt, the spread and price difference between the two should also initially increase, owing to the higher probability of a lower price for Subordinated debt versus Senior Unsecured debt – shown in Figure 2. This is an important condition of Subordinated debt for banks. The existence of Subordinated debt improves the asset value buffer for Senior bonds in the event of a bank default, but its primary goal is to provide central banks and regulators a tool with which to steady banks’ operations during periods of distress and thereby minimise the likelihood of disorderly banking collapses occurring.

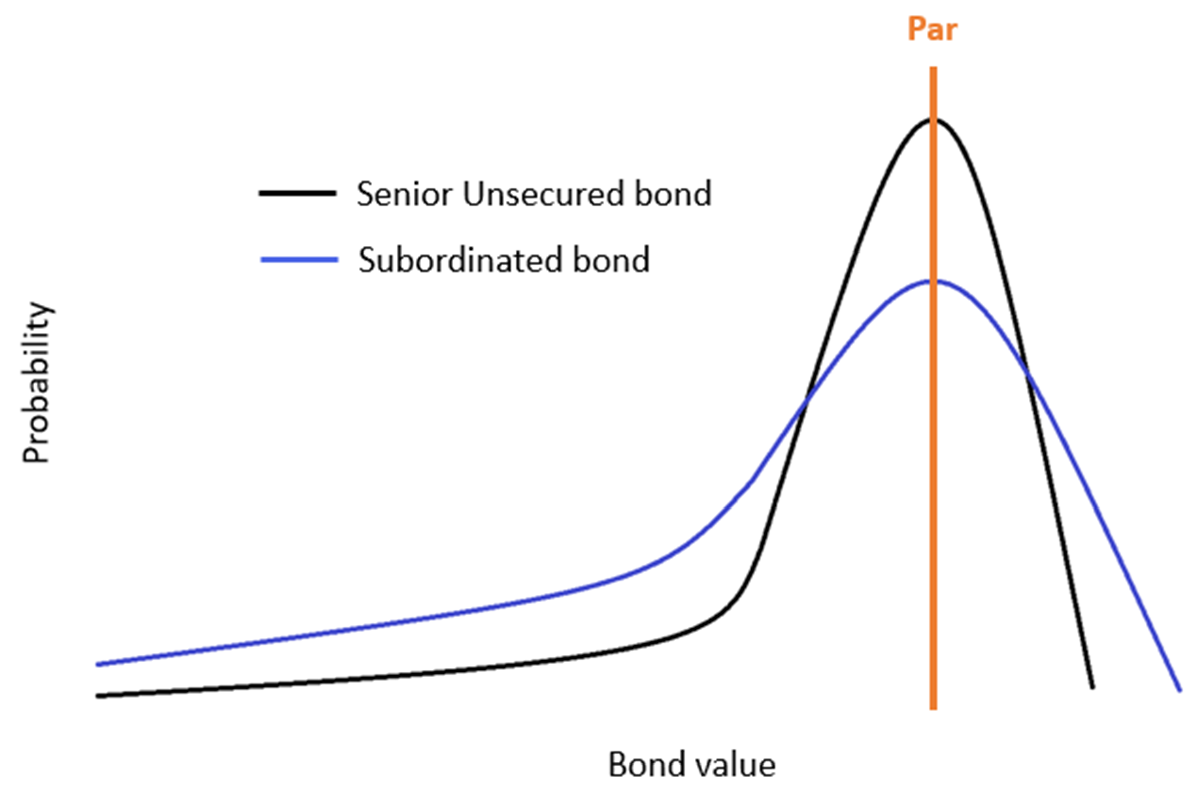

With that in mind, Figure 3 shows the additional return expressed as a ratio that investors would have received if they had bought Credit Suisse Tier 1 Capital notes versus Credit Suisse Senior Unsecured bonds, up until around two weeks prior to the collapse.

Figure 3: The changing return ratio between Credit Suisse Senior Unsecured bonds and Tier 1 Capital notes

The ratio shown is based on credit spreads on Credit Suisse Senior Unsecured bonds (ISIN USH3698DDD33) and Tier 1 Capital notes (ISIN US225401AP33), from 1 April 2021 to 28 February 2023. Source: Bloomberg

As we can see, the average ratio over the preceding two years or so was around 2.3x. More importantly, just a couple of weeks prior to Credit Suisse’s collapse the ratio was almost exactly in line with this average. This indicated no meaningful change in the market’s relative return expectations of the Tier 1 Capital notes compared to the Senior Unsecured bonds, despite a more than threefold increase in the overall credit risk of Credit Suisse over the same period. Credit spreads on Credit Suisse Senior Unsecured bonds moved from around +130 in April 2021 to around +400 in February 2023 (3).

Therefore, despite significantly elevated risks associated with Credit Suisse – and the more material risks facing the Tier 1 Capital notes versus the Senior Unsecured bonds – just a couple of weeks prior to the bank’s collapse Credit Suisse Tier 1 Capital note holders were accepting a relative return that was broadly in line with the average over the previous two years.

Lesson 2: Credit risk is asymmetric, not linear. Investors must be appropriately rewarded for risk, particularly when risk is changing.

#3. It’s important to leave your behavioural biases at the door

As the risk/reward trade-off of an investment materially changes, so must portfolio positioning. Unfortunately, this reasonable and rational approach is not always followed by market participants. A behavioural bias known as loss aversion is one potential reason for this.

Loss aversion refers to the phenomenon whereby a real or potential loss is psychologically or emotionally felt more severely than an equivalent gain. The psychological fear of loss can cause investors to behave irrationally and make bad decisions, including holding on to bad investments for too long. This may have been the case for investors in Credit Suisse Tier 1 Capital notes in early 2023.

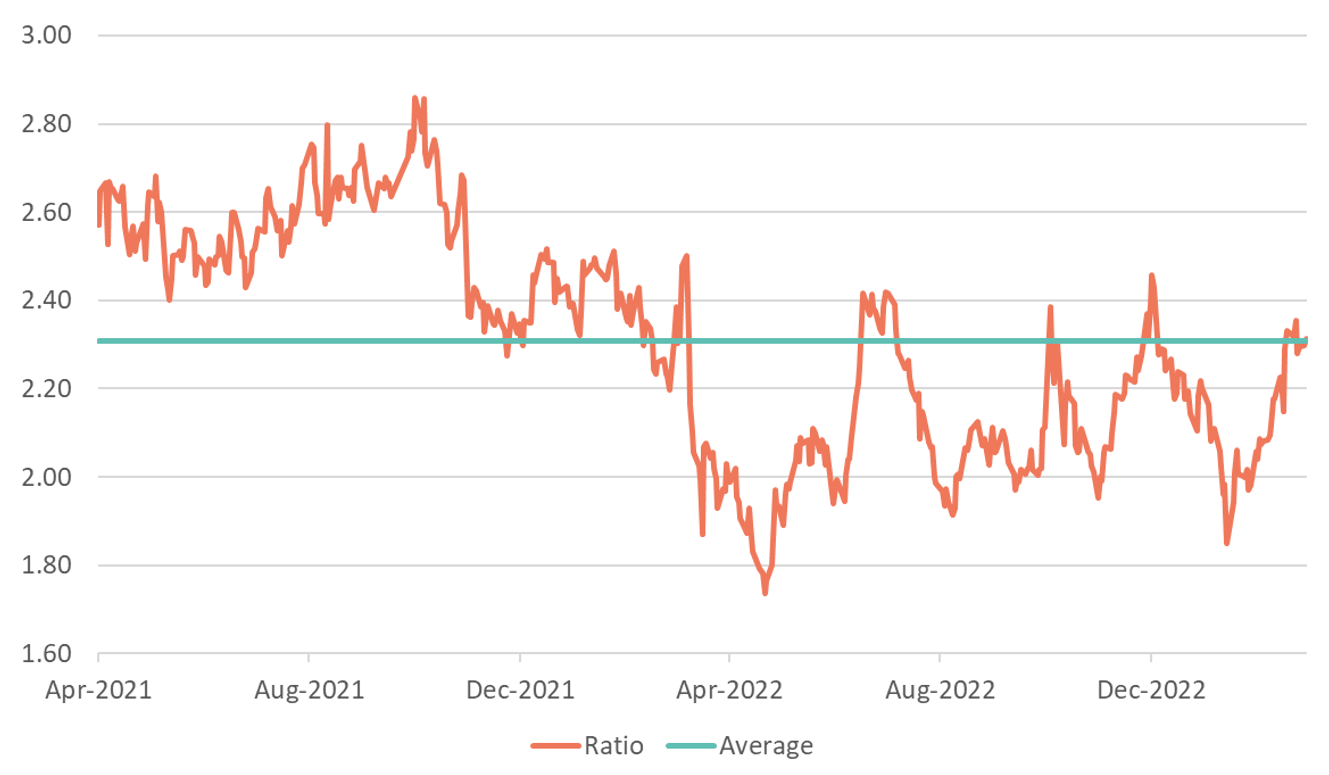

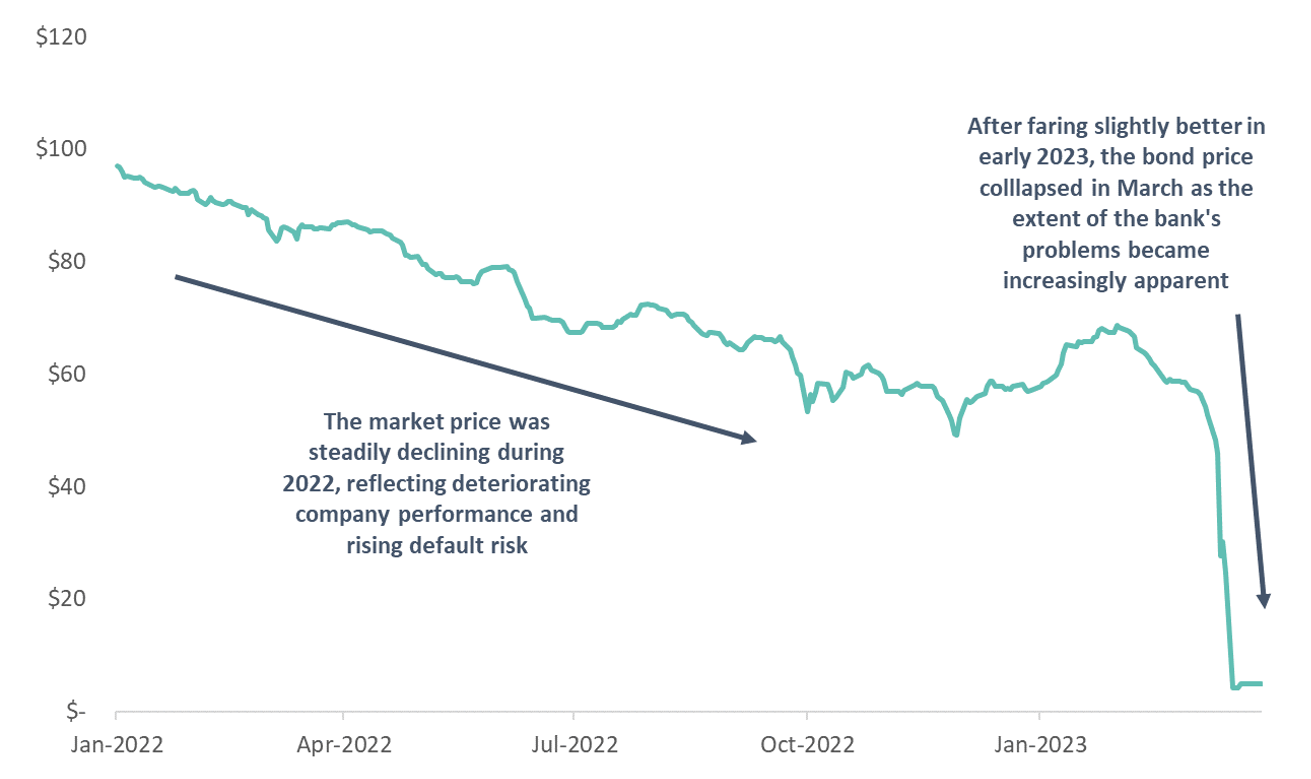

Figure 4 shows the price of these securities fell continually over 2022, with a moderate reversal in early 2023 before the securities were written off.

Figure 4: Credit Suisse Tier 1 Capital notes – market price

The price is shown for Credit Suisse Tier 1 Capital notes (ISIN US225401AP33), from 1 January 2022 to 31 March 2023. Source: Bloomberg

So why did so many bondholders hold on to their positions, particularly in early 2023 when there was a marked increase in default risk?

It may have been due to a lack of understanding of the risks associated with Tier 1 Capital notes, or perhaps most bondholders were passive rather than active investors. Or it might have been the result of an inadequate assessment of the risk/reward trade-off, as investors focused on the absolute level of potential return rather than how the level and shape of default risk had changed.

Or perhaps the fear of loss caused investors to behave irrationally and hold on to a bad investment for too long.

Lesson 3: As the risk/reward trade-off of an investment materially changes, so must portfolio positioning. Fundamentally-driven active investors who leave their behavioural biases at the door are best placed to behave rationally and make informed investment decisions.

First Sentier Investors’ Global Credit team are fundamental investors, which means we analyse every bond we invest in. A ‘four eyes’ approach requires each credit assessment to be reviewed by a senior member of the team, to reduce the likelihood of anything being missed and endeavour to ensure the outcome is fair and balanced.

Dedicated credit analysts work independently from the portfolio management team, thereby limiting the potential for behavioural biases to affect portfolio positioning.

These building blocks have helped us avoid defaulting issuers over a long period of time and ensure all exposures are appropriately sized given their risk profile.

1 fund mentioned