What can we expect from inflation?

It has been noted by some economic observers that Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has, in 2021, been consistent in one aspect of his predictions about inflation; that he’s consistently wrong. The message, as we’ve discussed here in the blog throughout the year, is that inflation is transitory. Base effects will ensure inflation turns to disinflation with the passage of another year, and capitalism’s supply response will solve the bottlenecks in global commodity supply chains.

We’ve also held the inflation-is-transitory view for two major structural reasons related to wages.

The first is that without persistent wage increases, inflation itself cannot persist. The second is that much lower levels of unionised labour than decades past, and much higher investment in labour-displacing automation, will serve to keep a lid on any rising aggregate wage claims. Consequently, structural downward pressures on wages, will keep a lid on inflation.

The conclusion is bullish for equities, and the fall in US 10-year Treasury bond yields from near 1.80 per cent in February this year to nearer 1.15 per cent accords with our view. It seems the majority agree. A recent Bank of America survey of 240 Global Fund Managers revealed less than a quarter (22 per cent) believe inflation will accelerate in the next year. Almost three quarters believe Jerome Powell’s message – inflation will be transitory.

And, in the US, implied inflation appears to have settled down too. The difference or spread between the yield-to-maturity of US Treasuries and TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities) have largely flattened out at between 2.2-2.4 per cent for ten years and between 2.3 and 2.6 per cent for five years, suggesting fears of serious inflation were short-lived.

Inflation is transitionary

Nevertheless, it is vital to test the theory and examine the view of the contrarians. So, what are the arguments against inflation being transitory?

Well first, some believe that the bond market’s sanguine view on inflation and therefore rates has more to do with Jerome Powell’s ability to convince and sway bond traders than it has, to do with inflation being permanently confined to the history books.

In the US, rent prices represent a third of the consumer price index (CPI’s) components, and rents are beginning to creep up. According to one analyst, US real estate portal Zillow reported US rents rose seven per cent year-on-year in June. And while that was measured against a weak June 2020, the monthly gain was 1.8 per cent. Meanwhile, a study by another real estate portal Zumper revealed average rental prices for one-bedroom apartments rose another seven per cent in July, and rent for an average two-bedder rose 8.7 per cent.

Those rent increases and other are perhaps steering the general public to a different view of inflation than that held by financial market participants. By way of example, a recent University of Michigan consumer sentiment survey, revealed a near 13-year high in inflation expectations for the next 12 months and expectations for five years elevated at nearly three per cent.

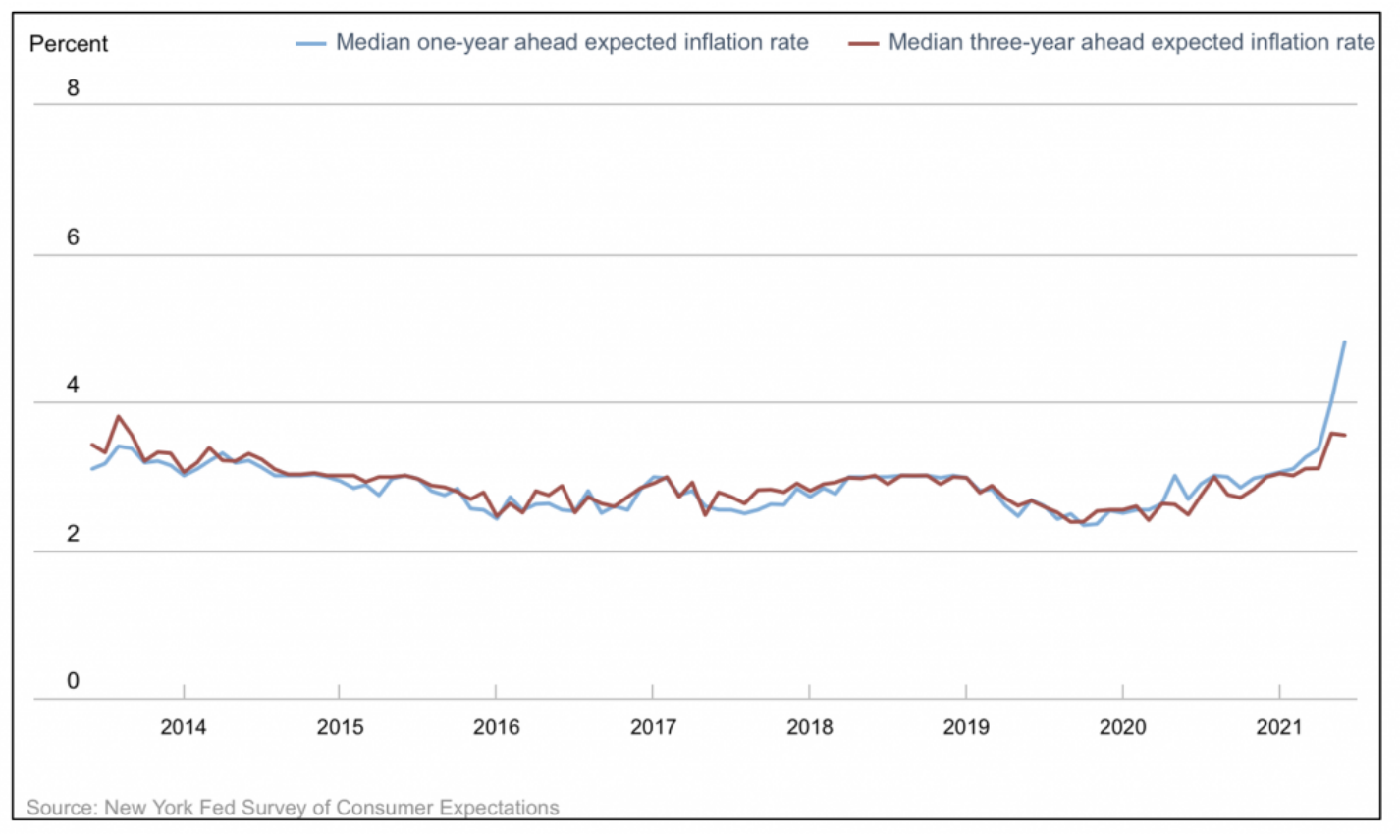

Meanwhile, the June ’21 New York Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Expectations (Figure 1.) revealed the highest inflationary expectations – 4.8 per cent – since the survey began (admittedly the survey began in 2013 – between the GFC and now).

Figure 1. Median one and three year ahead expected inflation rate

It is worth noting however that the expected inflation rate over three years, at 3.5 per cent, remains lower than in 2013, when it peaked then at 3.8 per cent. In 2013 US Ten-year bond yields varied between 1.65 per cent and 2.8 per cent.

Another argument advanced by the bears is that inflation is currently surging. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, year-on-year growth in inflation – as measured by headline CPI – has surged from 0.2 per cent in May this year to 5.4 per cent in June.

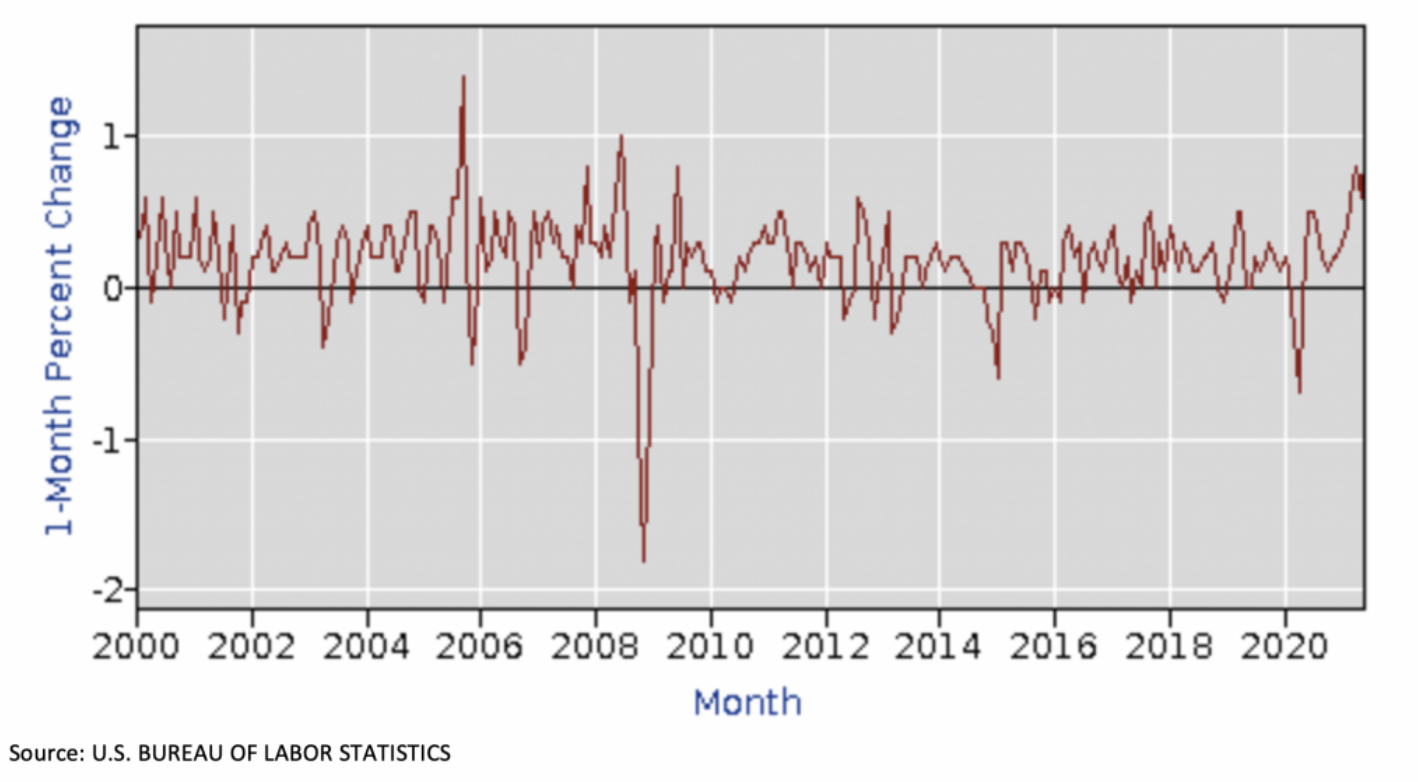

But as Figure 2 reveals there is yet to accumulate convincing evidence that the current bout of price rises is anything outside the normal range. And considering the lack of preparedness by producers for the surge in demand so quickly after the pandemic began a surge in prices should come as no surprise. For it to persist however would indeed be surprising.

Figure 2. 1 month percentage change in CPI for all US urban consumers June 2021

Inside of normal ranges, it arguably matters not what levels of inflation actually exists today. As long as long-term inflationary expectations settle somewhere between two per cent and three per cent – the market might just take a higher level in its stride. Indeed, we’ve seen more evidence of inflation in the first half of calendar 2021 than in many, many years and yet the bond and equity markets appear very relaxed.

Some commentators note even if monthly CPI numbers come in at very low levels for the remainder of the year, the annual gain in the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index issued by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis will be above three per cent. And if the June increase were to persist for the remainder of 2021, year-on-year PCE will be almost five per cent at the end of 2021.

Investors however can add and they can multiply, and with trillions of dollars at stake, it’s a long bow to draw believing such numbers at the end of the year would come as a shock.

The Fed is gradually revising its inflation target

The US Federal Reserve is however gradually revising its inflation target higher. It was less than two per cent at the end of calendar 2020. It jumped to almost 2.5 per cent in March this year, and it now sits at just under 3.5 per cent. There is indeed a possibility of further upward revisions but such increases would have to be massive and persistent to change five-and ten-year expectations – the sort of time frame that matters to equity investors.

For the reasons described above, we believe inflation will be transitory. And even if longer term expectations settle somewhere higher than they are today, we believe the market will come to accept a higher level than the ultra-low levels of the recent past. We also believe that the Fed and the RBA have clearly articulated the idea that they will remain ‘behind the curve’ – not raising interest rates until inflation is sustainably towards the upper end of their target bands. That would require wage growth, and while some sectors of the labour market are experiencing wage growth, the return of immigration – once we get on top of this virus – will put paid to that.

The market likes to have something to worry about, and professional investors sound wise, and their services necessary, alerting investors to imminent storms. But as Charlie Munger once observed, what witchdoctor gained fame and notoriety prescribing two aspirin.

While circumstances are dynamic, at this stage, investors do not need to be concerned. In any case it remains more important to identify and acquire high-quality business, those rapidly growing, those with pricing power and those with scarce and high-quality assets. Such businesses should carry a high weighting in investors’ portfolios even if inflation shocks.

2 topics