‘What do we have to believe from here?’ Our follow up memo, 12 months on …

Almost 12 months ago to the day, we published a memo on how we are thinking about market valuations. We would much prefer to not have to write a follow-up, but recent market movements have predicated that we communicate our thoughts to our small number of trusted clients. This is a version of our most recent memo that was sent on February 4, re-printed here for public consumption.

Like the last ‘market’ memo, it is the combination of hours of hard work from both Andy Simon and Tom Cowan. We are at that time of the cycle again where we are seeing big declines in growth (particularly technology) company share prices.

Since we started investing in the late 1990s, we can count six other times we have witnessed this magnitude of share price decline (50% plus) in our universe of growth businesses. Despite being well into the seventh, it never feels any easier.

We have always thought that our biggest competitive advantage over our time frame of investing (10+ years) is our ability to remain emotionally stable when share prices are down 50% or more and seem to be falling at a rate of 5% a day. This is as true today as it has ever been.

While there is a long list of things we are not good at, we think this is one of our key strengths that has allowed us to compound your capital for almost 17 years at over 25% per annum (net of fees).

Internally, we obsess about our businesses and how they are performing every day. We don’t measure this in share prices. A share price is just the price we are paying on any given day to buy a portion of a business. Rather we are thinking about revenue and earnings. This is much easier with our unlisted businesses where we don’t have Ms Market informing us daily of the price at which they are willing to buy or sell these businesses.

As you know, we don’t normally write memos about our views on the overall market except when things are at extremes. As it happens, we have felt the need to write one of these notes early in every calendar year for the last three years!

Almost exactly one year ago we wrote a memo titled “what do we have to believe from here?” in which we argued that public software as a service (“SaaS”) businesses were imputing lofty projections of future growth and profitability that we did not necessarily believe were achievable.

Little did we know that the release of the memo would coincide with peak valuation multiples for these businesses (we’re afraid this was pure luck — as you know we have no special talent in picking market cycles).

Fast forward one year and how times have changed. And fast. The past three months have proven to be one of the worst periods on record for listed technology businesses. While the NASDAQ Composite Index, comprised of many of the fastest-growing technology and other businesses, is “only” down 14% from its all-time high, listed SaaS businesses have fared much worse.

The Bessemer Venture Partners Emerging Cloud Index (“BVP Index”) is down 36% from its all-time high on 9 November 2021 , with many of the highest growth businesses down between 50% and 70%. In fact, over 40% of the NASDAQ is down by more than 50%.

So how are we thinking about the current environment? Is this the start of a great unwind of liquidity and a 2000 bubble burst re-run? The scariest part of thinking about this question is to realise a number of us here at TDM were actually investing in 1999–2001 (at least we can say ‘we were there!’).

Let us start with a little bit of history…

The Dot Com era vs today

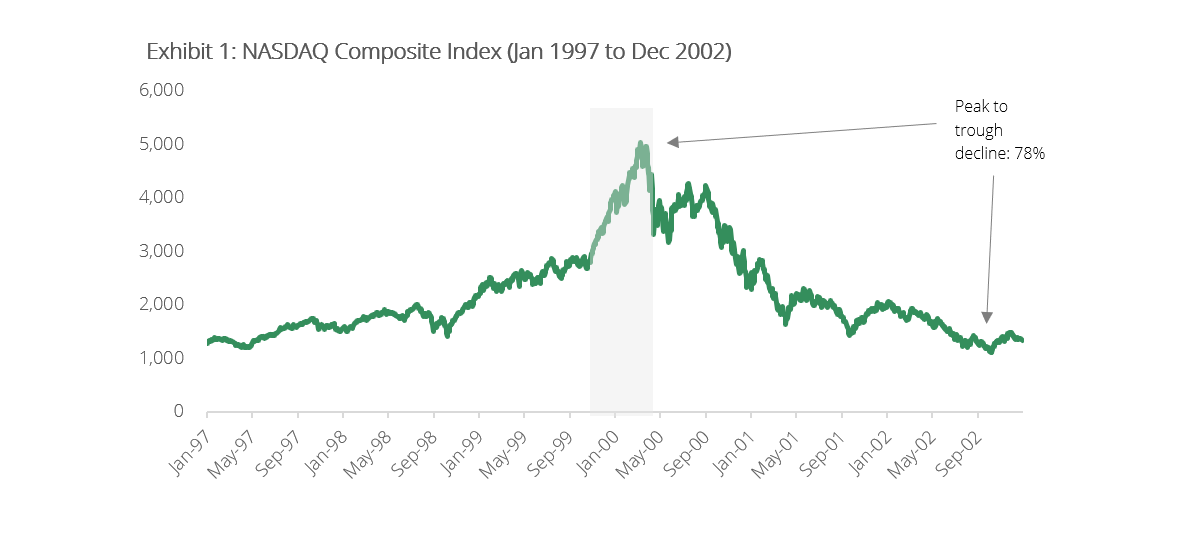

In March 2000, the NASDAQ hit a peak of 5049 before beginning a tumultuous decline. The index was coming off a record period of growth, increasing by 4x in a little over 3 years, including doubling in the seven-month period from August 1999 to March 2000. The peak to trough decline was 78%, with the trough occurring in October 2002, a full 2.5 years after the peak. This is the “dot com crash”. The index did not surpass its prior peak until July 2016 — a full 16 years from the prior peak!

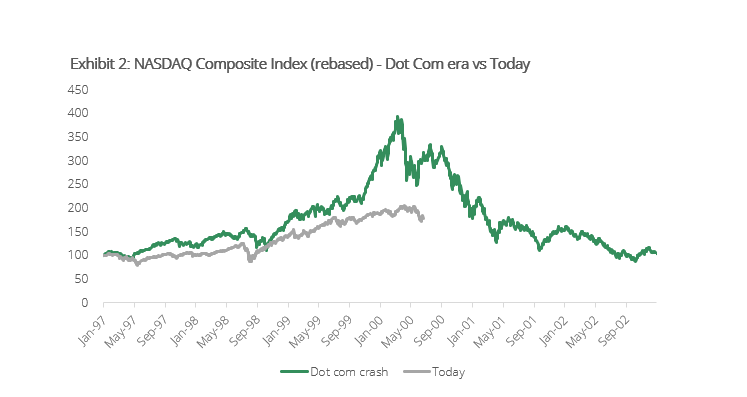

The past 3 or so years have been another strong period of growth for the NASDAQ, increasing by 2x from August 2018 to an all-time high of 16,057 in November 2021. Since then, the index is down 14% on the back of global macroeconomic fears of sustained higher inflation and the prospect of higher interest rates to combat this. This has naturally given rise to many pundits calling a similar dot com style crash to what was experienced in the early 2000s. While we will reserve judgment on the macro issues, we believe comparisons to the early 2000s are misguided (to say the least).

While the NASDAQ’s gains over the past 3 years mirrors that of the late 90s / early 2000s to some extent, in the latest period we have not experienced the extreme “melt-up” that was seen in the final seven months leading up to the dot com crash.

We can’t help but to give some anecdotal evidence to set the scene at the time, as it starts to paint the picture of the craziness of the dot com era.

One of the older members of the team who shall remain nameless recalls walking into his first day at work in mergers and acquisitions (“M&A”) in February 2000. He was excited. Having interned the prior Christmas at one of the leading fund managers in Australia and having read almost every Buffett book ever written, he thought he had some idea on how to value businesses. His first project was to produce a valuation table for his new boss.

The conversation went something like this …

Boss: “The best metrics to value these types of technology businesses are Enterprise Value to clicks and Enterprise Value to unique visitors”.

Young wannabe investor: “Excuse me? What did you say? We are going to merge two businesses based on the number of clicks each website has?”

Boss: “Yep, that is the best way to value these businesses as they have no revenue”.

There are many examples globally of the madness that was going on back in 2000. IPOs such as Open Communications which opened over 400% up on day one to become a multi-billion-dollar business…only to be bought for $7m four years later.

Never has there been more billion-dollar businesses go public that ceased to exist within a few years of the crash. In Australia — Looksmart, Davnet and One Tel. In the US — Webvan, Pets.com, eToys.com. And who can forget the outright frauds such as Enron and Worldcom.

1999 to 2000 was by far the craziest time we have lived through from a growth investing perspective. Hands down.

Granted, there are pockets of exuberance in markets today. We have observed some high-flying earlier stage private SaaS businesses raising funds at 100x+ annual recurring revenue (“ARR”).

But this appears localised to sophisticated venture investors who can tolerate the risk of overpaying for assets for the opportunity to make a fund-returning investment. Also as most of these deals are done with preferred equity, under most circumstances the investor will at least get their capital back. This risk-reward profile is completely different to investing in the ordinary shares of a public company where you have no downside protection.

What about dot com era valuations?

While forward-looking valuation data going back to the dot com era is patchy, the NASDAQ Index peaked at approximately 6x next twelve months (“NTM”) revenue in February / March 2000, compared to approximately 4x NTM revenue today. However, looking at index aggregates does not tell the full story given the wide mix of businesses. It is more instructive to look at a representative sample of software and technology businesses at the time.

Cloud computing did not exist in the dot com era. The only software business in the BVP Index today that was listed during this time is Adobe. So we cannot do an exact comparison of now versus then for these businesses. But this is an important point — the business models of the leading SaaS businesses today look very different to the business models of those that existed in the dot com era.

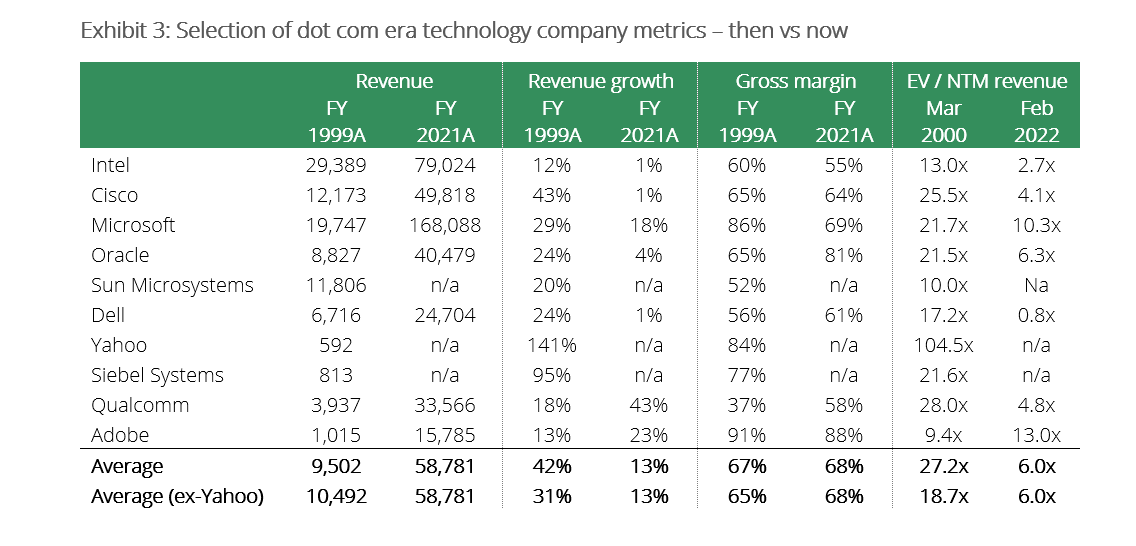

Exhibit 3 shows a series of metrics for 10 of the largest software and technology businesses at the peak of the market in early 2000. Most of these are household names and all but Sun Microsystems, Yahoo and Siebel Systems remain listed today. While these were all real businesses, generating real revenue and gross profits and growing at attractive rates, the valuations were crazy taking into account the quality of the revenue streams (i.e. non-recurring). The average business in this group was trading at 27x NTM revenue, or 19x excluding Yahoo as an outlier.

Besides Oracle with its large maintenance and services revenue, these businesses were largely devoid of the recurring subscription revenues that define the modern SaaS business. Microsoft generated the majority of its revenue selling licensed versions of its Windows and Office software, Cisco primarily sold hardware for networking purposes and Qualcomm sold chips for wireless handsets. Exactly what they were selling doesn’t matter, the point is that most of their revenue started at zero each year. Whereas a typical SaaS business will start the year with virtually all the revenue from the prior year . This revenue visibility and predictability makes forecasting a SaaS business easier than the software businesses of the prior era and thus warrants a higher valuation multiple.

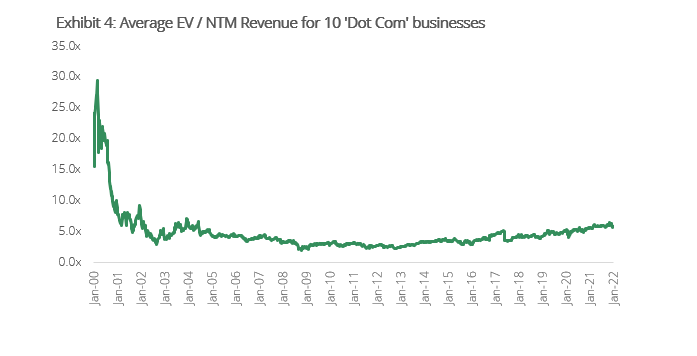

For the businesses on this list that are still listed, we can see above how different the multiples are today compared to the dot com era. Exhibit 4 below shows how this looks over time for the average revenue multiple across this group. While we would expect multiple compression as a business matures, the dot com era was clearly an aberration.

While each business has its own story, we will touch on just a few.

Microsoft is trading at c.10x NTM revenue today — half the multiple it reached in 2000 — while growing revenue at 18%, operating earnings at 21% and generating a 42% margin.F Subscription revenue now makes up most of the base (compared to close to zero in 2000).

Adobe is an interesting one — back in 2000, the business was doing c.$1bn of revenue, all in one-off software sales. Between 2001 and 2005, it did not grow revenue at all. Over the last 10 years, it has transitioned into a SaaS business with $16bn of revenue and 50% EBITDA margins growing revenue and earnings at c.20%. Yes, the revenue multiple is up to c.13x NTM — but the business model then vs today is far from comparable when it comes to quality, size and competitive advantage.

Oracle is the only business on the list that could, at that time, be considered comparable to the SaaS business models of today with a large maintenance and ongoing services revenue stream at c.50% of revenue back in 2000. Today, SaaS businesses with c.20% revenue growth are trading at 5x to 6x NTM revenue, not 20x like Oracle was in 2000. Interestingly Oracle has traded between 4 and 6x NTM revenue between 2002 and 2021 and today has a share price of only c.2x where it was trading in 2000 despite revenue growing over four-fold to $40bn.

Oh, by the way, interest rates in 2000 were over 6% for everyone who obsesses around the impact of every interest rate move for fast-growing businesses.

Public SaaS drawdowns — how low can we go?

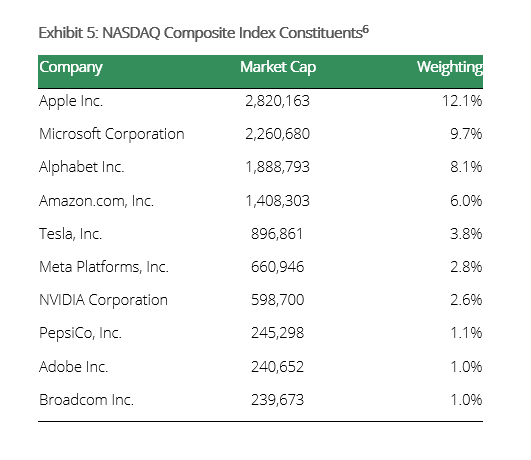

It is also important to understand that the NASDAQ doesn’t tell the full story today. As a market-cap-weighted index and with the top 10 constituents making up almost 50% of the total market cap, it is heavily influenced by the performance of these 10 businesses. These are some of the largest and most profitable businesses in the world and all but Tesla are growing their top-lines at <20% this year.

While these are all phenomenal businesses, they are not representative of high growth businesses more broadly. The other quirk of the NASDAQ is that it isn’t just technology businesses. For example, mature consumer businesses PepsiCo and Costco are in the top 20 index weightings.

To show the real pain in the listed technology world, we turn to the BVP Index. While this does not capture every high growth software or technology business listed in the US today, it does capture a broad index of high-growth public SaaS businesses and is therefore a better representation of growth businesses than the NASDAQ.

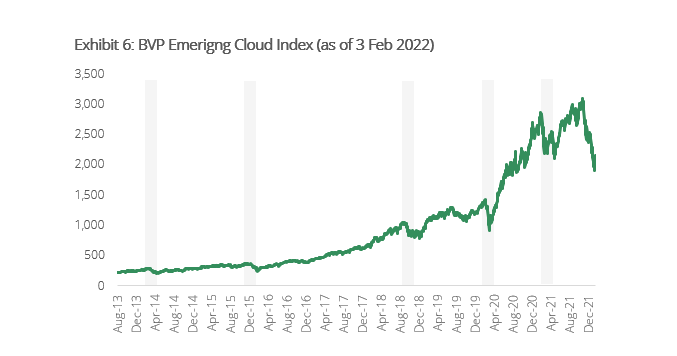

Looking at this index tells a very different story, with the index down 36% over the past three months. Perhaps even more telling, the average decline from 52-week high share price for the index constituents is 48% and 10% have declined by more than 70%. While not quite dot com era declines, the reality is that the true growth companies have experienced a substantial decline in their valuations in recent months that is being obscured by the technicalities of how the NASDAQ is calculated.

The chart above shows the BVP Emerging Cloud Index since inception in August 2013. The index performance over this period has been nothing short of exceptional, increasing by nearly 10x, representing a 30% compound annual growth rate (“CAGR”). This has handily outperformed the NASDAQ and S&P 500 with 17% and 12% CAGR’s respectively. While the chart looks almost like a straight line up, the law of large numbers conceals some substantial drawdowns over this period.

The ones to note are:

- 27 February 2014 to 28 April 2014 the index declined by 27% and took 10 months to surpass the previous high;

- 1 December 2015 to 9 February 2016 the index declined by 36% and took 7 months to surpass the previous high;

- 14 September 2018 to 20 November 2018 the index declined by 25% and took 5 months to surpass the previous high;

- 19 February 2020 to 16 March 2020 the index declined by 35% and took just 3 months to surpass the previous high;

- 12 February 2021 to 13 May 2021 the index declined by 26% and took 6 months to surpass the previous high.

Each of these drawdowns were short (1–3 months), sharp (>25%) and recovered to surpass previous highs at an increasing pace (except for the latest drawdown in Feb — May 2021, which took a little longer but still got there).

What does this mean for the latest drawdown in which the index has declined 36% over a three-month period? We will refrain from making ourselves look silly by calling a market bottom. However, significant drawdowns like this have historically provided some very good opportunities for strong returns over the medium term.

Public SaaS valuations over time

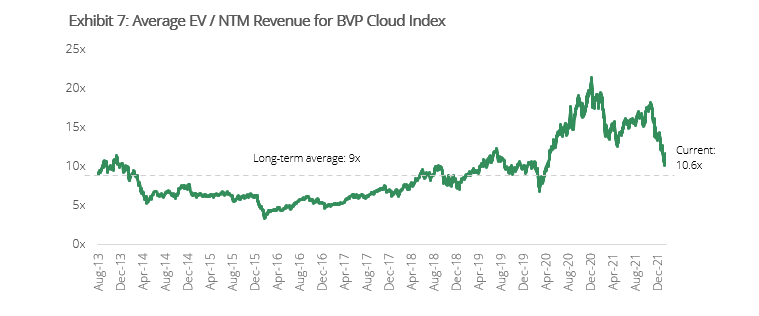

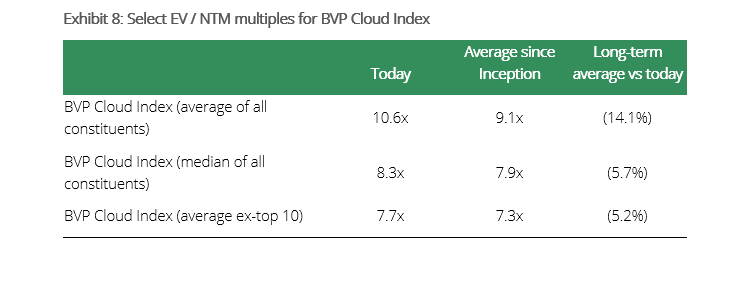

A cursory look at average SaaS business multiples would suggest that today’s levels — 10.6x NTM revenue for the BVP Index — are still high relative to history. After all, there’s still more than 14% to go for multiples to revert to the long-term average of 9x NTM revenue.

We believe this perspective misses an important point; that the EV / NTM revenue multiple for the average company in the BVP Index has deviated from the median company over the past few years. The median EV / NTM revenue multiple today is 8.3x, slightly above the long-term levels of 7.9x and much closer than implied by looking at averages.

This is a result of a small number of businesses pulling up the multiple for the index. If we exclude the top 10 highest multiple businesses from the index, we get an average multiple today of 7.7x, much lower than the multiple for the whole group. We think this is a better representation of where the typical SaaS business is trading today.

Whether you look at the median multiple or the average multiple excluding the top 10, the message is the same — SaaS multiples today are not far above their long-term average levels.

One final point to make here — President Trump’s tax reform, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, will impact any historical comparison of revenue multiples. This law was enacted on 22 December 2017 and effectively cut the total corporate tax rate from c.39% to c.25%. The effect of this is that every dollar of revenue generated is worth more to shareholders, as less is being paid away to the government. On our calculations, the equivalent revenue multiple under the new regime is c.1.4x higher than prior. It is important to keep this in mind when comparing today’s multiples to historical levels.

So where to from here? Any analysis of valuation is incomplete without considering the forward outlook for these businesses. Remember stock prices represent the market’s expectations for all future cash flows. While historic valuations tell us something about the past, they don’t tell us anything about the future.

The four most dangerous words in the English language — this time is different

We do not possess a crystal ball (sadly). Nor do we profess to have any special ability to predict the future better than anyone else. However, we have been investing in software and technology businesses for over 20 years and have had the benefit of experiencing how much the world has changed over that time.

There have never been more fast growing, at-scale software businesses with amazing unit economics than there are today. These businesses are going after very large markets and in many cases disrupting existing industries or creating new ones entirely.

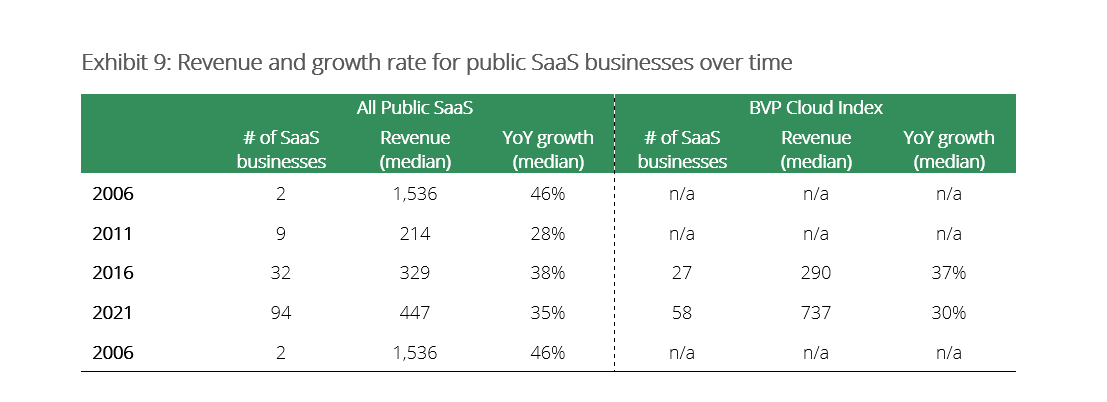

Exhibit 9 below shows that in 2006 there were only two public “SaaS” businesses — Adobe (which hadn’t been through its SaaS transition at this point) and Salesforce. As of the end of 2021 there were 94.

In 2011 there were 9 listed SaaS businesses with median revenue of $214m and growing at c.28%. Based on data from Bessemer Venture Partners, cloud penetration of total IT spend was approximately 5% in 2011. These cloud customers were mostly small businesses and early adopters. Large enterprises and governments largely refused to host anything in the cloud out of concerns over reliability and data security. SaaS was far from a sure thing at the time.

By 2016 cloud software was becoming more accepted and had increased to approximately 15% of total IT spend. By this time there were 32 publicly listed SaaS businesses with median revenue of $329m and growth rate of 38%. This was a good period for listed SaaS businesses but many also hit a growth wall and / or were acquired in subsequent years. A number of these businesses reached approximately $200–300m in revenue and then decelerated significantly, including Fleetmatics, Marketo, Opower, Workiva, Box, Mindbody and Constant Contact. Only 24 remain listed today.

Fast forward to 2021 and we now have 94 public SaaS businesses with median revenue of c.$450m growing at c.35%. Never has there been more businesses at this scale and growing at these rates. Cloud software penetration is now c.30% of total IT spend and is on track to represent the majority of software spend in coming years as the issues that had previously put a ceiling on adoption are no longer relevant. Enterprises and other large institutions are scrambling to upgrade their technology stacks to modern cloud-based systems. Meanwhile new upstarts are launching every day with fully cloud-based modern infrastructure, giving them a competitive advantage against incumbents.

Early SaaS pioneers like Salesforce, Workday and ServiceNow set the bar high by sustaining high rates of growth for many years. However, these businesses were outliers for their time and commanded premium multiples for it. There are many more SaaS businesses that hit a wall on the journey to $500m and were acquired or fell off the radar. Today half of the 94 public SaaS businesses have blasted through the $500m mark while continuing to grow at high rates. What was once the exception has become the norm.

Granted, not all these businesses will be the amazing compounding machines that Salesforce and other early SaaS businesses have been. And valuation is still an important consideration — you can overpay for a great business. But for the investor willing to do the work, the opportunity set in SaaS land has never been greater.

What do we need to believe from here?

This brings us to the all-important question: is now the time to be investing in growth businesses? We will answer this question with reference to the expectations framework we laid out in last year’s article. The caveat is that everything we do at TDM is bottoms-up and based on an in-depth qualitative and quantitative analysis of each business — so this is intended to be illustrative only.

Referring to exhibit 9 above, the median SaaS business in the BVP Index generated c.$740m in revenue and grew at 30% last year. The median EBITDA margin was 8%.

We assume we purchase this hypothetical business at the current median multiple of 8x NTM revenue. Using our framework this business would need to sustain revenue growth of approximately 25% p.a. for the next 5 years to generate a 20% compound annual return over this period — below the current pace of growth. If the business can sustain the current rate of 30% p.a. growth over this period, we would expect to generate a return of 25% p.a.

Not every public SaaS business will grow at these rates for this period of time. Some will permanently decelerate. A number will be acquired or fall away into obscurity. But in a world where many are sustainably growing revenue at 30%, 40% or even 50% per annum, the hurdle required to achieve an attractive return has rarely been lower. And we would argue that interest rates going to 2%, 3% or even 5% is irrelevant if revenue increases 3 to 5-fold over five years.

We acknowledge that, all else equal, higher interest rates will increase the discount rate required to discount future cash flows and reduce the present value of those future cash flows. We have never used market discount rates in our valuations.

Rather we use our own hurdle rate of 25% — our annual return target — to determine the attractiveness of an investment. This does not change with interest rates. Nor do the exit multiples we use to calculate these returns, as we always seek to use a “through the cycle” multiple.

In the framework above we assume the hypothetical mature business will be valued at 25x NTM free cash flow in 10 years. In a world where the interest rate on 10-year government bonds is 1%, as they were approximately one year ago, one could easily justify using 50x NTM free cash flow as the appropriate terminal value multiple.

This translates to a 2% free cash flow yield. For a mature business growing at a mid-single digit rate, this translates to a 6% — 8% annual return beyond year 10. This seems reasonable in a world of 1% interest rates.

But what about a world where the 10-year interest rate is 5%?

Without going into all the technicalities, a more appropriate terminal value multiple, in this case, might be approximately 17x NTM free cash flow. This translates to a 6% free cash flow yield and an annual return of 10% — 12% beyond year 10. Again, this seems like a reasonable excess return for a mature, low-growth business.

We do not know if interest rates will be 1%, 3% or 5%. The assumption of 25x NTM free cash flow seems like a reasonable middle ground under most normal circumstances. Of course, if interest rates go to 10%, then the 25x terminal multiples becomes harder to defend. However, in that world, there are likely other significant macroeconomic events taking place which would warrant re-evaluating the growth prospects of this business. We are constantly digesting new information and re-evaluating the future growth prospects for all the businesses we invest in.

To tie a bow on this thread, the thing we worry most about at TDM is not what interest rates will be or whether we are in an inflationary or deflationary environment. Rather it is whether we are right or wrong about the businesses we invest in.

With such a long-term investment horizon, evolution of the competitive advantage and quality of the people and culture behind the business matter more than the vagaries of the economic cycle. We are much happier dedicating our mental energy to solving these things.

What now?

None of this is to say that investors should be closing their eyes and blindly throwing money at public SaaS businesses. Picking the right businesses requires a deep understanding of competitive advantage, unit economics and, perhaps most importantly, the quality of the people and culture of the business. This is what we do every day at TDM. In fact, when we look at our portfolio today our expected returns have never been higher at approximately 35 to 40% per annum for the next 4 years.

Does this mean that SaaS stocks won’t fall any further? No. It is impossible to say how far the pendulum can swing when sentiment shifts.

We believe that rather than playing Chicken Little and fearing that the sky is falling in, now is the time to turn to offense and make some selective purchases in high-quality, long-duration growth assets at attractive prices. And that is exactly what we are doing.

Appendix:

Full assumptions in regards to what hurdle needs to be jumped over to achieve a 20% return from here.

1. We are looking at 5 and 10-year returns based on a valuation of the business in years 5 and 10;

2. The business reaches maturity in year 10, defined as growing in-line with nominal GDP;

3. At maturity the business will generate a 30% FCF margin;

4. We exit the investment in year 5 at a valuation that allows the next investor to generate a 15% IRR

5. A “through the cycle” valuation multiple for a mature business of this nature is 25x NTM free cash flow (equates to 7.5x NTM revenue at a 30% FCF margin);

6. No dilution from share issuance;

7. Starting cash on balance sheet of $850m (c.10% of market cap);

8. All free cash flow generated is retained in the business.

Footnotes

Consists of 58 publicly listed SaaS businesses with market capitalizations greater than $1bn and can be accessed publicly from (VIEW LINK)

As of 3 February 2021.

In fact for many enterprise SaaS businesses with net revenue retention of >100%, their revenue grows each year without having to add any new customers.

Based on Capital IQ consensus forecasts for the year ending 30 June 2022 (FY2022).

Based on Capital IQ consensus forecasts as at 3 February 2022

As of 3 February 2022.

This list includes SNOW, NET, DDOG, ZS, TEAM, BILL, ASAN, CRWD, SHOP and OKTA.

Based on applying 25x free cash flow to free cash flow before and after the tax change.

TDM proprietary analysis. May not be exhaustive given definitional issues around what constitutes a SaaS business.

Salesforce.com, Success Factors, NetSuite, LogMeIn, Cornerstone OnDemand, Responsys, Ellie Mae, Adobe and Constant Contact.

Bessemer Venture Partners State of the Cloud 2020.

https://medium.com/tdm-tidbits/what-do-we-have-to-believe-from-here-d3571f26e0f7

See appendix at the end of this note for the full assumptions.

Free cash flow yield is defined as NTM free cash flow divided by the enterprise value.

Never miss an insight

Enjoy this wire? Hit the ‘like’ button to let us know. Stay up to date with my content by hitting the ‘follow’ button below and you’ll be notified every time I post a wire.

Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

1 contributor mentioned

.jpg)

.jpg)