What matters for 2025 and beyond

Investors marvelled, and headlines flourished when seven large tech company shareholders saw their share prices surging in concert. The pile-on that ensued generated wild returns that were subsequently described as magnificent. And so the Magnificent Seven were born.

But fewer investors realised all the Mag 7 had in common was that their share prices had risen significantly and at the same time. No different to the FANG, FAANG, FAANG+ and MAMAA stocks before them and the Nifty 50 before that. What tied them together was their share price performance. Oh sure, commentators tried to find some commonality, such as pricing power, but Tesla has subsequently demonstrated it doesn’t have pricing power, and yet it was included. No, all that tied them together was a rising share price and perhaps that they were all big.

While the disruptive force of AI and its demands on cloud computing would combine to attract investors to a theme on which to base their bets, the rally was just another predictable replay of the consequence of combining disinflation with positive economic growth.

When disinflation and positive economic growth coalesce, at least since the 1970s, the share prices of innovative companies with pricing power have done well. This time around, it happened to be AI-exposed companies that investors bet on as the most innovative with pricing power.

Coming out of the slump in 2022 - itself the result of a rapid shift higher in interest rates - Price Earnings multiples had collapsed. By way of example, the PE ratio for the S&P600 small cap index hit the lowest level for a quarter-century, except for the GFC.

Two years later, the commentators now warn a bubble has formed.

Pointing to a banana taped to a wall that sold for US$6.2 million (including buyers premium), the boom in meme coin ICOs (Initial coin offerings) and even the US$100,000 achieved by Bitcoin, many commentators suggest a market crash is imminent.

I remember when an untitled painting by famed neo-expressionist artist Jean-Michel Basquiat sold for US$110 million in 2017. Some suggested then that asset markets were, therefore, in a bubble. I might have sympathised with them and yet the market rallied for at least two more years.

There needs to be a mechanism that takes away the fuel, the air in that bubble.

What then triggers the crash? What causes investors to turn 180 degrees and switch from supporters to opponents? A little more on that subject in a moment.

Another line of argument for a bubble points to the sharp rise in records set by various equity valuation measures.

Figure 1., reveals the price-to-book ratio for the S&P500, showing it is now at almost 5.5 times book.

But so what? So what if it goes to 5.6, 5.8 or even higher? What is the level it should not go beyond? And why should it not go beyond that level? Who decides?

The problem with displaying ratio charts across time and revealing new records is that the accompanying discussion often fails to recognise the denominator’s role in the new record.

In the case of the S&P500’s price-to-book ratio, which now exceeds the highs before the tech wreck, a much more significant proportion of companies in the S&P500 today should, understandably, have far less invested in tangible assets on their balance sheets. Today’s successful companies aren’t the manufacturers or railroad operators of the past. Today’s success stories tend to be capital-light, IP-heavy businesses. I haven’t done the study comparing book value per share then and now, but I wouldn’t be at all surprised to see equity per share, or book value per share, is relatively lower.

Of course, having said that, prices will correct at some point. A market crash is a reasonably reliable event. Indeed, every US presidential term since 1901, except three democratic terms, has seen pullbacks in the market of more than 10 per cent. This next Trump term will be no different.

But the correction won’t be triggered by the price-to-book ratio exceeding some previously acceptable level.

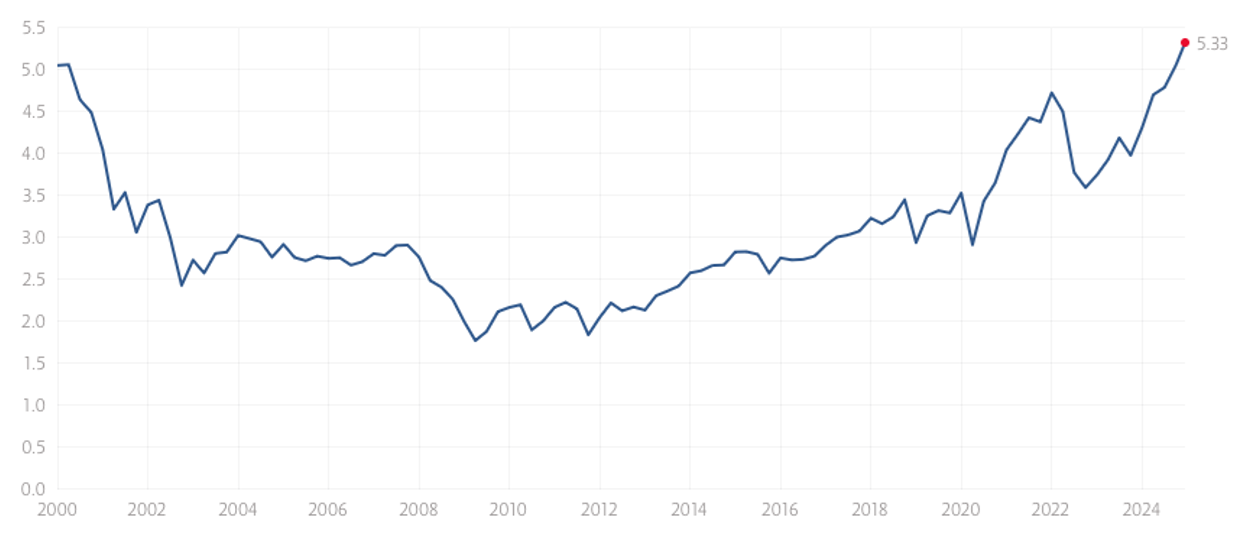

A similar argument might be made for Robert Shiller’s CAPE (cyclically adjusted price to earnings) ratio.

That ratio is now at 38.54 times, and while some investors like to adjust for the influence of the Magnificent Seven and calculate the ratio for the ‘S&P493’, it makes little difference - the ratio is elevated.

Figure 2. Shiller CAPE ratio

For the S&P500, the CAPE ratio is at a level exceeded only twice in the last 154 years. That was once during the tech bubble of 1999/2000 and more recently just after Covid struck and earnings were hammered.

The denominator for the CAPE ratio is earnings and those earnings are also playing a part in the ratio’s level again. The CAPE ratio’s denominator is the moving average of the last ten years’ inflation-adjusted earnings. In the last ten years, COVID hit earnings and that hit continues to influence the ratio today.

Once again, the equity market will eventually correct, but when it does, it will have nothing to do with an elevated CAPE. When it does correct it will be because investors see something on the horizon that might cause other investors to sell, triggering lower prices. We have now reached a stage were investors guess what other investors might guess!

What matters is not some ratio exceeding its previous high - we will see old records constantly smashed in our lifetimes.

One material factor that does matter is liquidity. As long as the party punch flows freely, the party will continue exceeding the time limits given to it by less experienced investors and observers. As long as the punch is flowing, ratios will continue to post records.

For those who worry more about the bubbles in peripheral assets such as banana art, NFTs, ICOs and Bitcoin, what I believe is essential to remember is first, yes, prices for these assets will crash again, eventually, but second, their elevated levels are sustained by mountains of global liquidity thanks to a debt binge after rates were cut to zero.

Likewise the elevated ratios are sustained by liquidity.

Liquidity

According to Crossborder Capital, about US$316 trillion in debt is outstanding globally. Assuming that the average term is about five or six years, then one would expect a fascinating vintage to require refinancing in 2026. That will be the estimated US$70t vintage of debt borrowed when interest rates plunged close to zero. Plenty took advantage of near-zero rates and borrowed for longer terms, but beginning in late 2025, or during 2026, some of this debt will need to be refinanced.

The liquidity required to refinance that debt is the same liquidity currently fuelling the so-called bubble in cryptocurrency ICOs, Bitcoin and artists sticking bananas to walls with silver duct tape.

Now, I am no Henny Penny warning the sky is falling. The redirecting of liquidity that begins in late 2025 or early 2026 is a process, not an event, so we could just coast on through it. And just as Australia’s Mortgage Cliff failed to materialise, the drawing of global liquidity to refinance debt may be nothing to worry about either.

But…what we know is heady prices are more vulnerable to a shift in sentiment. If by late 2025 or 2026, prices are even bubblier than they are today – thanks to a maturing of the current boom, then fears over the global ‘Liquidity Cliff’ (I just called it that), could be enough for some investors to take profits. And that could start a cascade.

What the wise do at the beginning, the foolish do at the end. By the end of this bubble you will see very late buyers still attributing their buying to the AI theme or the America is Great theme that prompted less inert investors to buy in 2022, 23 and 2024.

If there are enough of those late-to-the-party buyers, the sellers worried about a Liquidity Cliff won’t make a dent in prices. But if the buyers have all dried up, the selling will move prices, which will obviously trigger a rush of selling amid fear of even lower prices ahead.

So, there will be some pressure on liquidity, and some of that liquidity is necessary to sustain the current asset boom. Any reduction in liquidity makes markets more vulnerable to bad news, especially if price multiples are elevated. And while a redirection of liquidity can cause a crisis of sorts, it might merely be the shift in sentiment that triggers the selling.

But that’s possibly a year away, or more (or less)!

To those pointing to extended PE and Price-to-Book ratios as well as extreme Euphoria in peripheral assets I say watch liquidity ratios instead for a guide to 2025 and beyond.

In the meantime, investors should keep in mind bull markets can keep prices at stupid levels for longer than you can remain liquid betting against them. And bull markets climb a wall of worry. Even a conga line of bad news won’t disrupt proceedings, provided liquidity is adequate. Moreover, the co-existence of disinflation and positive economic growth should provide a supportive backdrop for equity investors in 2025.