What Microsoft’s Blizzard acquisition means for video game investors

Global X ETFs

Yesterday, Microsoft’s acquisition of video game maker Activision Blizzard was approved by shareholders, with 98% of shares voting in favour, but what does this mean for Microsoft?

While Blizzard makes many famous video games – Call of Duty, Overwatch, World of Warcraft – the firm has been declining for years.

Headlines have focussed on sexual harassment within the firm. Yet Blizzard’s problems extend beyond culture. Thanks to what gamers call “profit tunnel vision” and “greed”, the firm has alienated loyal players, killed its standing among gamers, and seen many talented developers resign.

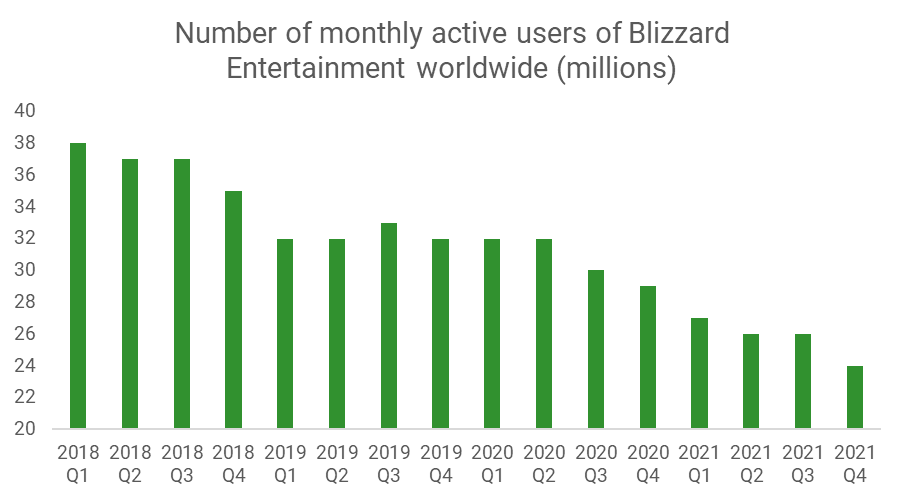

Since 2018, Blizzard has lost over 40% of its active users—with the number of people playing its games falling from 38 million to 24 million as of December 2021. Its core franchises are decaying. World of Warcraft, arguably Blizzard’s most important game, has lost two-thirds of its players the past 10 years. Overwatch has lost almost 80% of its weekly players in the past five years. While Call of Duty is losing market share to Apex Legends, a title from its competitor Electronic Arts.

While Microsoft has a long history of buying video game developers, the acquisition of a declining company has left many wondering what’s going on.

Why did Microsoft buy Blizzard?

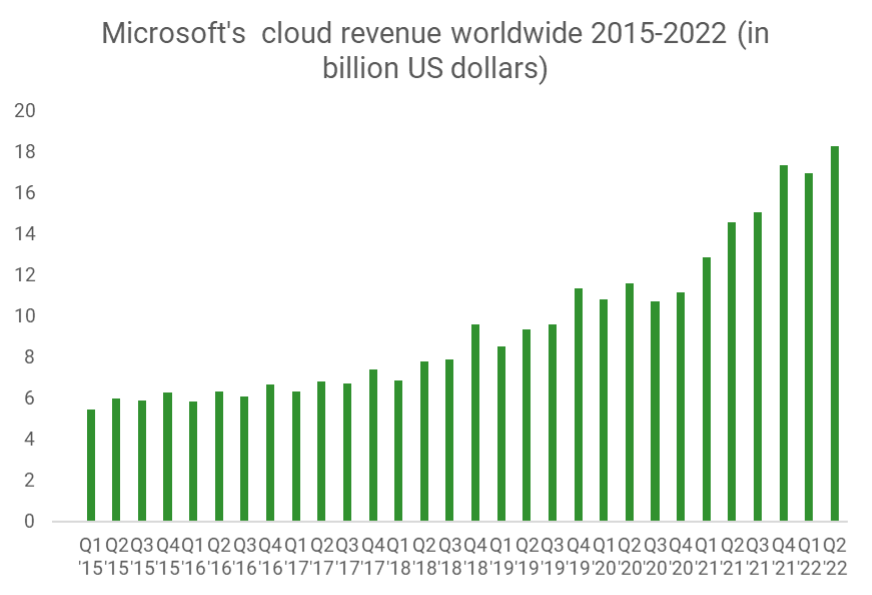

Microsoft bought Blizzard because it can help sustain growth in its cloud computing business. Cloud growth has been the central business strategy of chief executive Satya Nadella.

How this worked for Office is well known. These days, Office customers pay an ongoing subscription to use Word, Excel, PowerPoint, etc which are delivered via Microsoft’s cloud. Customers no longer buy them as CDs from their local tech shop every year.

Wall St 'loves' the subscription model – where customers rent rather than own software – as it makes revenue more recurring and predictable. It is also good for margins as customers buy directly from Microsoft rather than from shops, which take their own cut.

Source: Microsoft, Statista. Data as of Feb 2022.

As with Office, Microsoft hopes to stop gamers buying CDs from shops. Instead, Microsoft wants them to pay an ongoing monthly subscription to Game Pass, which is Microsoft’s cloud gaming service.

Game Pass works like Netflix and Spotify. For a monthly fee, you can play any game from a vast library. With Blizzard, the library will grow – making Game Pass service more attractive. Game Pass currently has 25 million subscribers. This number will increase as Blizzard’s 20 million-plus gamers migrate over.

As Brendan Keogh, a senior lecturer at QUT, pointed out: “With the , Microsoft has purchased a city of existing renters in…Call of Duty, Hearthstone and World of Warcraft…That’s tens of millions of players already… including many in the difficult-to-penetrate Chinese market playing Blizzard titles. All of these players can be farmed for more personal data and more rent.”

Where this leaves game publishers in an era of the FANGs

The final question is where the buyout leaves the other independent video game developers. Famous independent developers include Electronic Arts, CD Project and Take-Two Entertainment.

Historically, game development has been a very successful business model. Video games are software. And like all other software companies, it comes with unit production costs near zero. This makes margins high.

Yet in today’s market this model seems more challenged, as game developers get squeezed on multiple fronts.

First, their customers – gamers – are becoming more demanding. They are asking for better graphics, more free content, more immersive experiences, more anti-cheating surveillance. This all costs more money.

Second, their workers – devs and animators – have skills that are in ever-greater demand thanks to the tech boom. Many are leaving for the other tech companies, with higher salaries. While others are unionising and pushing for higher salaries directly.

Third, under pressure from Wall St, famous developers – whose share prices help determine the performance of video games indices – are taking fewer creative risks. These days, big developers are opting for franchises and sequels in ever-greater number. Thus, we have seen endless instalments of Call of Duty, Pokémon, Halo and all the rest—yet fewer innovative titles. In this aspect, the fate of video game developers resembles that of Hollywood studios like Disney, which nowadays make sequels and prequels (like Marvel) and write fewer original stories.

This has pushed blockbuster innovation out to the periphery of small developers, whose shares are often unlisted and therefore excluded from video games indices. The success of Untitled Goose Game by House House, a little-known Melbourne developer with just four staff, is a key example of this phenomenon in recent years. Wordle, invented by a British software developer in his bedroom during covid lockdowns, is another example.

Why the FANGs may be better for video games

Those wishing to access video games, may be better served by investing in the FANGMAN stocks: Facebook (Meta), Amazon, Netflix, Google, Microsoft, Apple and Nvidia.

These stocks are well positioned to access the key video game growth areas, including: cloud and mobile gaming, streaming and content, graphics cards and the metaverse. Several of them – especially Apple and Nvidia – already draw tens of billions of dollars of annual revenue from video games. While Microsoft is now the third-largest video games business in the world, behind Tencent and Sony.

Would you like to invest in the FANG ETF?

ETFS FANG+ ETF (ASX Code: FANG) offers investors exposure to highly traded next-generation technology and tech-enabled companies. FANG provides concentrated exposure to global innovation leaders. Find out how to invest here.

2 topics

1 stock mentioned

1 fund mentioned

Expertise