What quantum of government bonds do banks have to buy?

There are a bunch of big regime changes in Aussie fixed-income markets that are going to materially change asset-pricing. Our detailed modelling shows banks are going to issue about $168bn a year of wholesale debt, on average, for the next 3yrs as a result of: (1) APRA shutting the $139bn Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF); and (2) the need to repay the RBA the $188bn it very generously lent---at between 0.25% and 0.1% per annum---the banks under the ultra-cheap, 3-year Term Funding Facility (TFF).

Replacing the CLF will also require banks to buy government bonds as a substitute for the CLF, which currently counts towards the banks' all-important Liquidity Coverage Ratios (LCRs). The LCR represents the amount of high quality liquid assets (HQLA) banks hold relative to the net cash outflows (NCOs) they would suffer in a 30 day liquidity crisis. While we will return to this later, HQLA includes government bonds and cash on deposit at the RBA. It is a complex question as to precisely what the total dollar value of government bonds banks will ultimately have to buy over time, which this note will try to address.

The quantum of government bonds required by the banks to hit their 125% LCR buffers (or just a bit above the 100% minimum LCR mandated by APRA) will increase as the $188bn TFF is repaid, because this repayment process mechanically disappears an equivalent amount of excess cash that is currently on deposit at the RBA, and which is currently counting towards the banks' LCRs.

We are already watching the banking system make decent headway into both debt funding and government bond buying. Since APRA announced the shuttering of the CLF on 10 September 2021, there have been a raft of new public and private wholesale bond issues launched by the banks, including:

- A$2.8bn of a dual-tranche covered bond issued by Westpac in Europe;

- A$500m of a CBA green senior bond, which due to its very tight (41bps) spread only attracted $875m of demand;

- A$1.1bn of a Westpac RMBS issue, which was the smallest since 2012 and attracted just a $1.1bn book (compared to the $2.75bn RMBS issue Westpac completed in January 2020 on the back of a book north of $4bn);

- A to be finalised, circa $900m Macquarie GBP senior bond issue; and

- About A$731m of private placements from CBA, Westpac, and ANZ (as at close of business Friday).

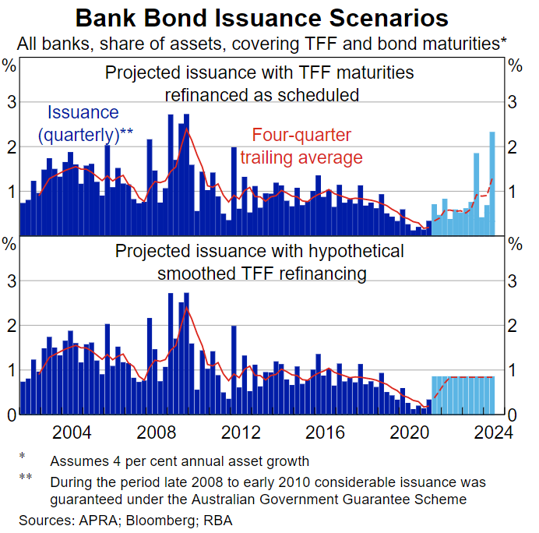

The RBA has recently published its own forecasts of the banks' likely wholesale debt issuance over time to repay the TFF, which are broadly similar to our own and are outlined in the two charts below. Here the RBA comments:

According to liaison, banks' current plans are to raise a sizeable amount of funds to repay TFF funding (on or before maturity) from wholesale debt markets, thereby at least partly reversing the process whereby debt issuance declined as TFF drawdowns increased. The bulk of scheduled TFF maturities occur in the September 2023 and June 2024 quarters. If banks issue new debt to replace TFF drawdowns in the quarter of maturity, this would require quarterly issuance as a share of assets at levels not seen in over a decade...However, banks are unlikely to refinance their TFF drawdowns right at the time they are scheduled to mature. In liaison, banks have flagged plans to issue bonds earlier than scheduled TFF maturities (‘pre-funding’). Banks can also terminate TFF repos early without any additional cost. Indeed, some banks have indicated willingness to terminate early and issue bonds at around the same time. These strategies would allow banks to spread the refinancing task over a period of time...This would serve to reduce the effect of refinancing on market conditions as well as offset the effect of approaching TFF maturities on their regulatory liquidity ratios.

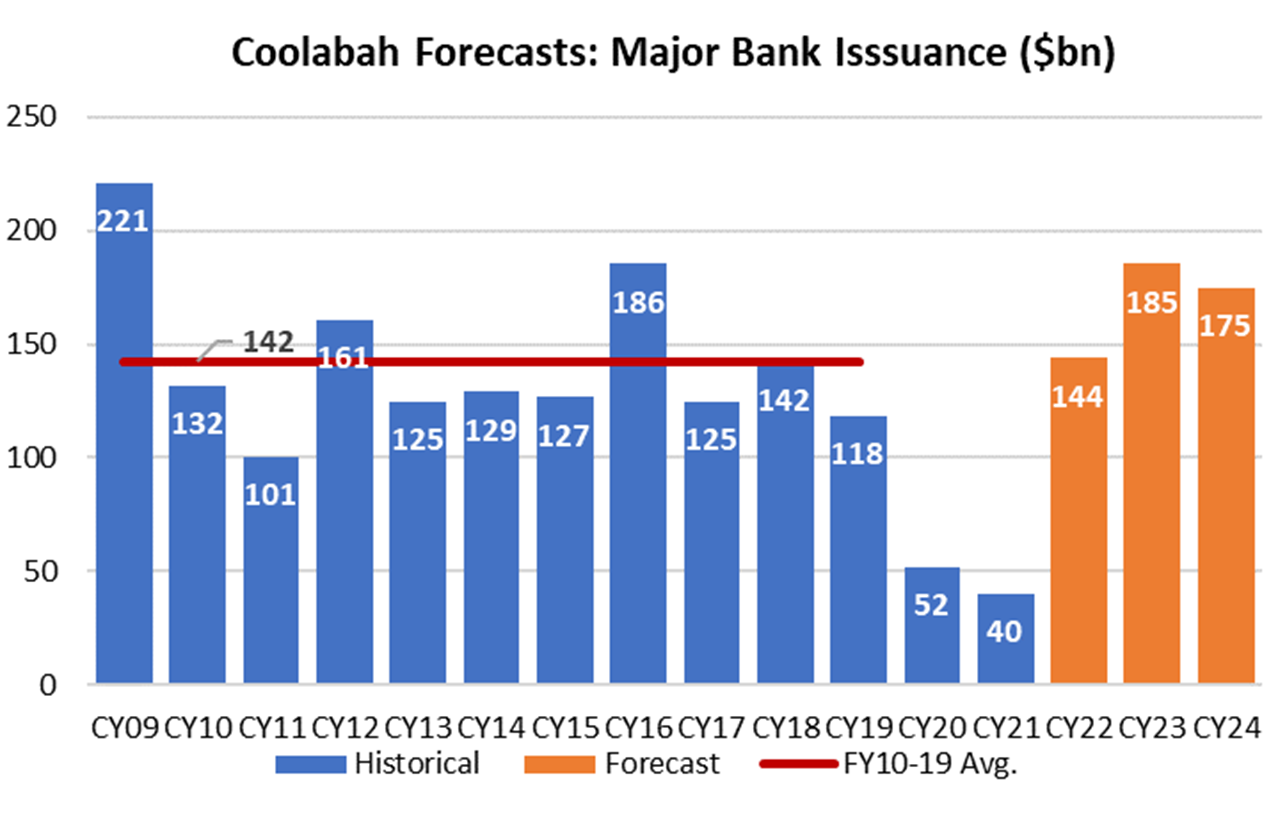

Coolabah's forecasts for major bank wholesale debt issuance, including certificates of deposit, project about $168bn per year over the next 3-4yrs compared to the $141bn average for the 10yrs to 2020. This includes both the debt issuance required to replace the CLF and buy government bonds plus the funding needed to repay the $188bn TFF (see chart below).

In preparing this analysis, we account for the banks' current funding positions, including any excess cash, and assume balance-sheet growth of 5% pa in concert with deposit growth of 4% pa.

All of this wholesale debt issuance will help normalise the credit spreads on both bank senior bonds and RMBS back to around the average levels evidenced in the post-GFC period, if not somewhat higher. This upward pressure on credit spreads on senior paper and RMBS will be amplified by the fact that banks will no longer be able to get away with the ruse of buying their own bonds under the CLF---including internal loans, other banks' senior bonds and bank and non-bank issued RMBS---and counting those relatively illiquid CLF assets as a substitute for government bonds for emergency liquidity purposes.

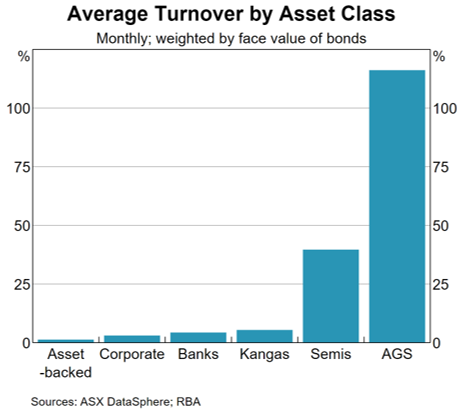

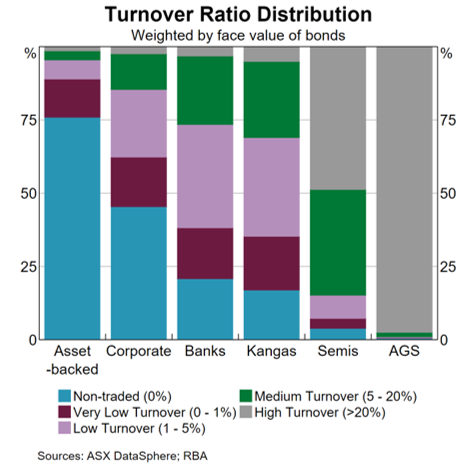

Interestingly, the RBA's latest research on the liquidity of bank senior paper and RMBS (the banks' internal loans, which made up 80% of the CLF, are almost perfectly illiquid) shows that secondary turnover is exceedingly low in comparison to the exceptional liquidity available in both the Commonwealth and State government bond markets (see two charts below).

As we've previously forecast, this will mean that 5yr major bank senior bond spreads have to climb from circa 45bps over the quarterly bank bill swap rate (BBSW) today to somewhere between 60bps and 80bps. The clearing level might be a bit higher given the dramatically reduced bank balance-sheet bid. (We sold all of our 5yr major bank senior paper at 35bps over BBSW in late 2020.)

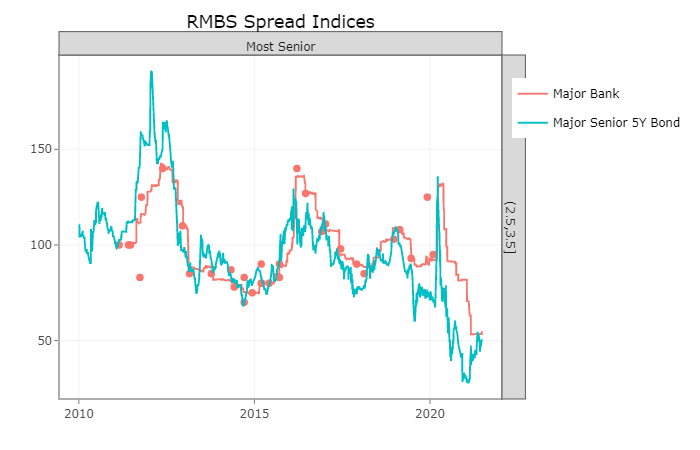

Since RMBS prices off the benchmark asset that is the major banks' 5yr senior bonds (see chart below), we should likewise see major bank issued, 3yr RMBS increase in spread from ~55bps today to somewhere between ~70bps and ~90bps (if not a touch higher). This overdue repricing will provide all investors with attractive entry points (again, we sold almost all our RMBS in late 2020).

Once the new clearing level for bank senior and RMBS spreads emerges, it should provide the banks with much deeper investor demand and associated funding opportunities.

What quantum of government bonds do banks need to buy?

In its recent letter to the banking system, APRA declared that it "expects to purchase the HQLA necessary to eliminate the need for the CLF" (our emphasis). HQLA refers to high quality liquid assets, which are three things: (1) cash on deposit at the RBA; (2) Commonwealth government bonds; and (3) State government bonds.

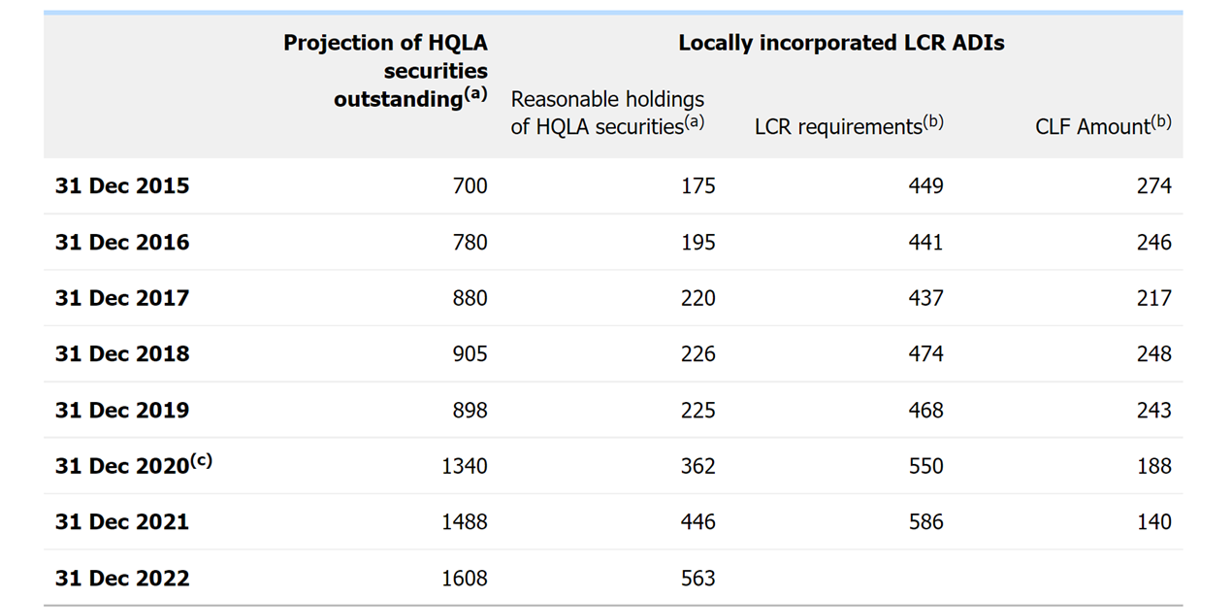

In this letter, APRA referenced the RBA's calculations on the HQLA available for banks to buy. Specifically, APRA commented that "the RBA has assessed that the AGS and semis that can be reasonably held by locally-incorporated LCR at the end of 2022 will be around $560 billion". By "AGS and semis", APRA meant Commonwealth and State govt bonds. The RBA's table summarising this analysis is enclosed below.

Coolabah's analyst team has more formally modelled Australian banks' demand for HQLA as a function of a range of factors, including, but not limited to:

- The RBA's bond purchase program (aka quantitative easing or QE), which creates new digital cash in the form of cash on deposit at the RBA (known as exchange settlement account, or ESA, cash). (When the RBA buys a bond, it deposits cash into the banks' ESA accounts.) This ESA cash counts towards the banks' HQLA;

- APRA closing the CLF by the end of 2022, which needs to be replaced by some form of HQLA if banks are below their LCR targets, which can include: (1) ESA cash on deposit at the RBA, (2) Commonwealth govt bonds, and (3) State govt bonds;

- The banks repaying the RBA the $188bn it lent them under the TFF, which mechanically destroys this same quantity of ESA cash (again when the RBA lends money under the TFF, it deposits cash in the banks' ESA accounts);

- Bonds that the RBA has bought under its QE program than then mature over time, which also destroys ESA cash;

- The change in the Net Cash Outflows (NCOs) that are a key determinant of the amount of HQLA a bank has to hold (where banks target holding HQLA worth about 125% of their NCOs). The NCOs are the expected cash-outflows banks would suffer during a liquidity crisis over a 30 day period; and

- Other variables, such as notes and coins, and HQLA held overseas.

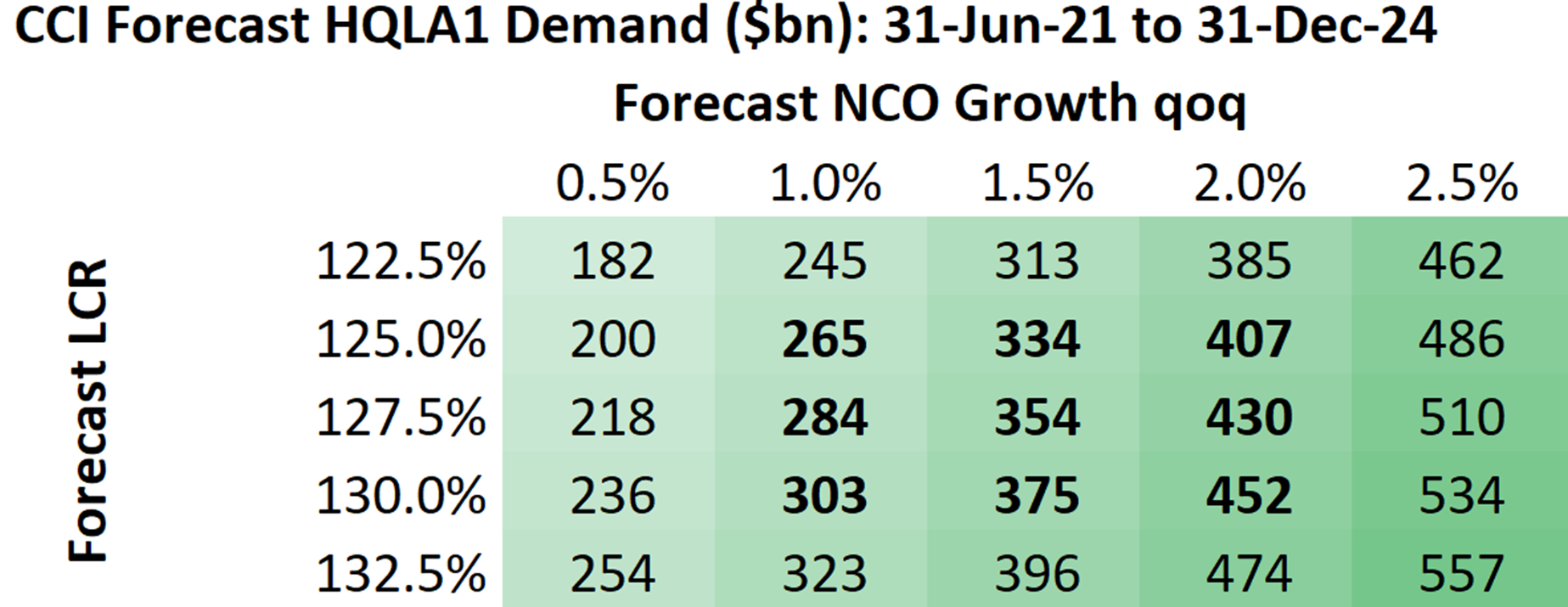

The table below shows the results for future HQLA demand through to December 2024 across all Australian banks. Note this assumes a very slow RBA QE taper dropping from $4bn/week of bond buying in February 2022 to $3bn/week in the following quarter, then $2bn/week and $1bn/week in the final two quarters. A faster RBA taper would bring-forward the banks' HQLA demand.

Observe that the HQLA forecasts are presented as a function of the banks' LCRs (vertical axis) and the NCO growth they experience (horizontal axis). Higher NCOs create much greater HQLA demand. Generally speaking, NCOs will be positively related to the banks' balance-sheet growth: so greater credit growth will drive higher NCOs, all else being equal (ie, assuming no change in the funding mix).

What we find is that accounting for the CLF closing, the TFF being repaid, the RBA creating new ESA cash via QE3, and many other factors, Aussie banks will probably want to buy between $250bn and $450bn of HQLA over the next 3yrs over and above the HQLA that they currently hold. Given the supply on offer via the Commonwealth and the States, that should be quite straightforward to execute.

Coolabah's estimates of $250bn to $450bn of HQLA demand are much higher than what the banks' sell-side analysts have estimated. We've seen some suggesting that the banks will not have any HQLA shortage due to the RBA's QE program. Yet we have accounted for a very large, $147bn QE3 schedule in our numbers above. We've also heard some sell-side analysts suggest that the HQLA shortage might only be in the order of $40bn, which is almost one-tenth the size of what we have estimated.

It is true that the banks have time on their side: the HQLA demand really ramps-up much more sharpy in about 12 months. Having said that, banks tend to be very conservative, and normally seek to get ahead of these regulatory hurdles. This is precisely why they are so busy issuing wholesale debt right now, and why they have started buying government bonds.

One counter-argument is that banks could issue all this wholesale debt and sit it in ESA cash earning 0.0% interest pa. While this is true, the revenue drag compared to the alternative of holding positive yielding government bonds is likely to be unacceptable for most. Furthermore, APRA does appear to be imploring the banks to "purchase" HQLA, presumably on the basis that the excess ESA cash on deposit at the RBA will disappear over time as the TFF is repaid and QE bonds mature.

2 topics