What really drives rotations from growth to value stocks?

One of the prevailing investment themes of the past decade has been the long-term underperformance of value stocks versus growth stocks. Many have blamed falling bond yields, low inflation and the scarcity of economic growth.

But recently the tables have turned. Value has staged a remarkable comeback alongside a significant rise in bond yields and economic optimism.

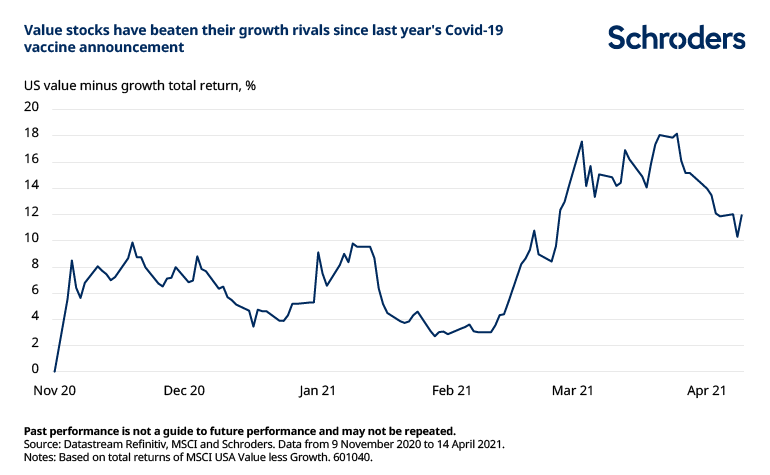

For example, since Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine announcement, US value stocks have beaten their growth counterparts by around 12%.

Naturally, these market moves have reinforced the narrative that higher interest rates and growth expectations are driving the rotation from growth to value.

Although this may be true, history shows that the link between value returns and such economic variables is unstable. Namely, changes in interest rates do not consistently translate into outperformance or underperformance.

Given the relatively wide valuation disparity between value and growth stocks, value is likely to continue to outperform over the coming years.

But the idea that its recovery largely hinges on the path of interest rates, inflation or economic growth is probably overstated.

The duration argument

It is commonly assumed that growth stocks are a larger beneficiary of falling bond yields than value stocks because their expected cash flows extend much further into the future.

This means they have longer “duration” and are therefore more sensitive to changes in the discount rate used to value those cash flows.

The risk-free real (inflation-adjusted) interest rate represents one component of the discount rate. So all else being equal, when real bond yields fall, growth stock prices should benefit relatively more than value stock prices. For the maths behind this effect, see our previous articles here.

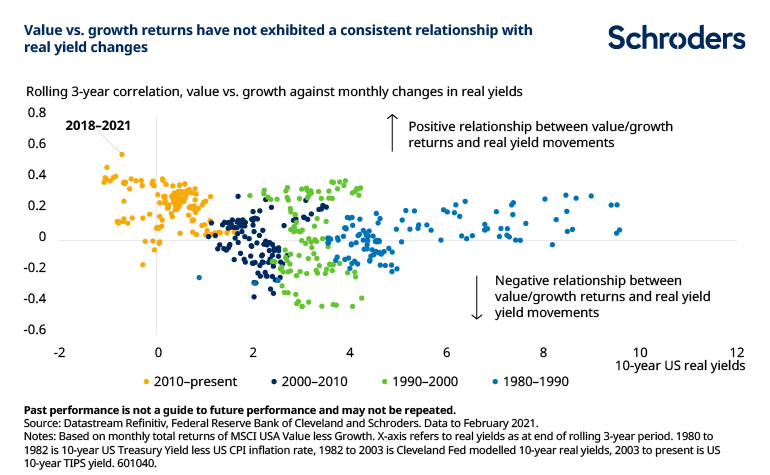

Although value versus growth returns have been positively correlated with changes in real bond yields in recent years, the relationship has not been consistent over time.

For instance, over the past three years, the correlation between the performance of the MSCI USA Value versus Growth Index and yield changes on 10-year US Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) has been +0.55.

Yet over the past five decades, the average correlation has been +0.07 and has oscillated between being positive and negative, as shown in the chart below.

Rather than the experience of the past three years being representative, it has actually been an outlier. In no other rolling three-year period since the 1990s has the correlation been this high.

This implies that value does not automatically beat growth when real yields rise and vice versa.

The 2010s do show a more positively skewed relationship compared to the long-term average and some have attributed this to the low yield environment.

However, correlations were also positively skewed in the 1980s, which was certainly not a period of low yields, undermining the argument that low yields are responsible for the stronger relationship.

So what else might explain the unstable correlation? Well, for a start, changes in real interest rates are often accompanied by changes in growth and/or inflation expectations, which can affect future expected cash flows.

There may also be a change in the risk premium associated with those cash flows, which is an additional component of the discount rate.

All of these effects can offset each other, making it difficult to disentangle the impact of interest rate movements on value versus growth returns.

The speed of the move matters more

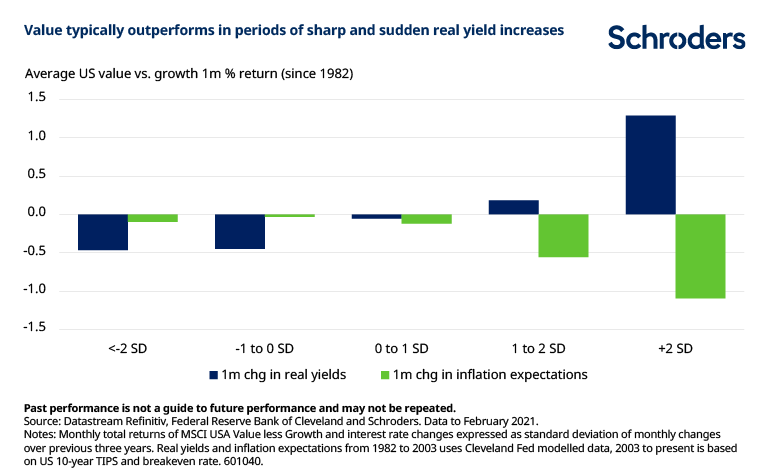

Another contributing factor may be the speed of rate movements. Performance seems unrelated to gradual increases, while sharp and sudden changes are associated with having a large impact (see chart).

For example, value has on average outperformed when real yields have risen by more than 2 standard deviations (e.g. +25bps today). But when real yields have risen by one or fewer standard deviations, relative returns have on average been flat.

Meanwhile, real yield decreases have generally been better for growth returns than for value, regardless of the size of the move.

Performance is also generally unrelated to small changes in inflation expectations, as measured by the yield difference between nominal and inflation-protected US Treasury bonds.

In fact, contrary to popular belief, value stocks have tended to underperform growth stocks in periods where inflation expectations have increased by 1 standard deviation or more.

This may be because, assuming nominal yields remain unchanged, increases in inflation expectations push real yields lower, resulting in even higher valuations for long duration growth stocks.

Value stocks are not necessarily cyclical

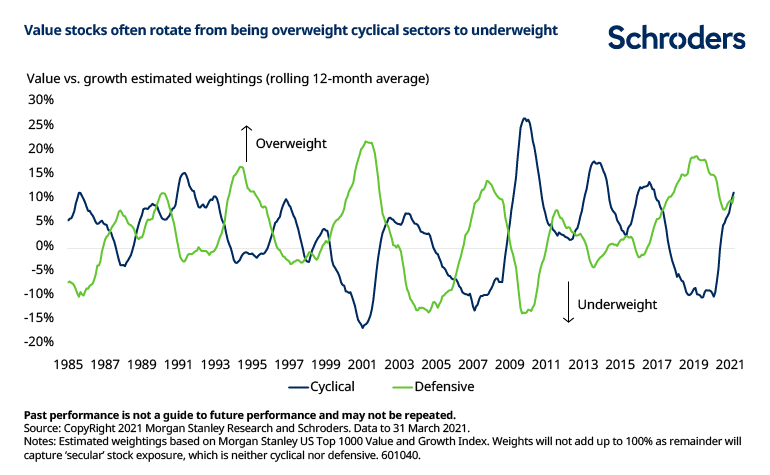

An alternative explanation for value’s erratic relationship with bond yields is that its cyclical exposure relative to growth is not constant over time.

Cyclical sectors generally outperform when economic growth strengthens and yields rise, while defensive sectors outperform when economic growth slows and yields fall.

Although value was overweight cyclicals from 2009-2017, it was actually underweight cyclicals and overweight defensives from 2017-2020.

The net result of such rotations is that value stocks have, on average, had a very similar cyclical profile to growth stocks, as shown in the below chart. Investors should not assume anything permanent about value’s cyclicality and hence correlation with bond yields.

Although value has a strong cyclical bias at present, history suggests that this exposure could wane in the future.

Profit upswings typically correlate with turning points for value

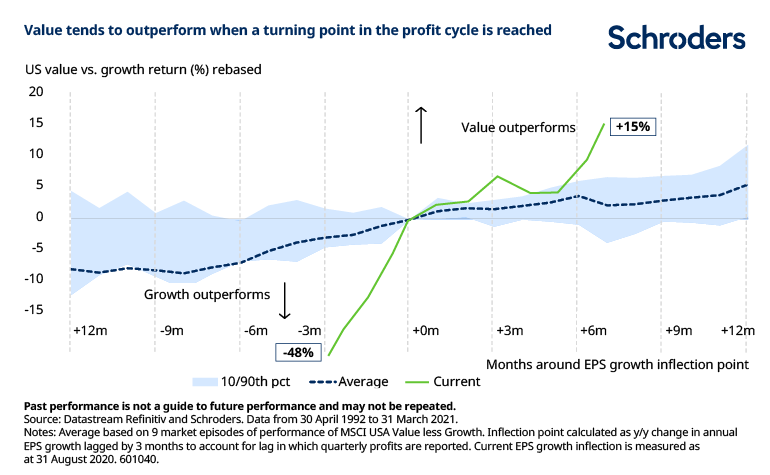

One economic indicator that tends to signal rotations from growth to value is when earnings-per-share (EPS) growth is at an inflection point.

For example, in the past, value stocks have outperformed growth stocks by 6% on average in the 12 months after EPS growth bottomed, as shown in the following chart.

Given the severe drawdown experienced last year, value has also come roaring back recently.

This pattern is intuitive. When profit growth is scarce, investors are more willing to “pay up” for faster-growing companies in the form of higher price-to-earnings multiples.

But when profit growth is relatively abundant (or at least expected to be), investors are more choosy about valuations, leading growth stocks to de-rate as cheaper stocks swing back into favour.

However, this link between value and profit upswings can sometimes fizzle out, particularly following an economic recovery, when cheaper companies re-rate and leave the value universe.

After all, neither value nor growth indices hold a constant set of securities over time. As growth companies mature, their valuations can suffer at which point they may exit the growth universe.

Similarly, when cheaper companies begin attracting investors, value stocks may see their valuations rise and exit the value universe.

This may be one of the reasons why value’s outperformance weakened in 2010 and 2017, as its cyclical exposure had already normalised (see previous chart).

Is this a sustainable value rally or another short-lived rotation?

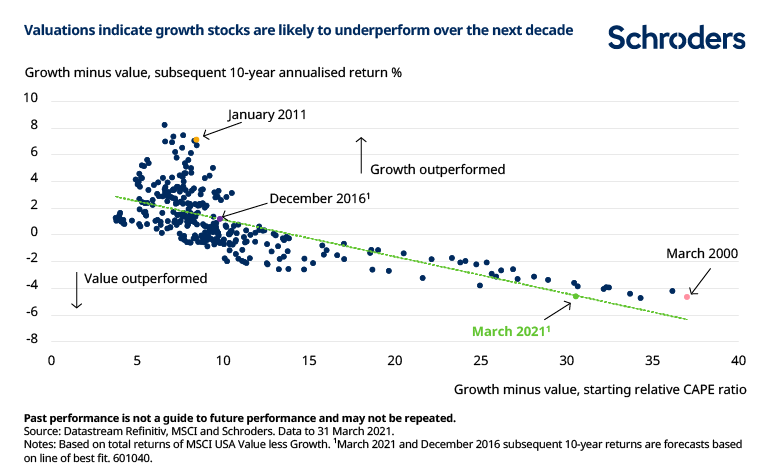

One consequence of a decade of growth outperformance is that valuations are now stretched to levels that would have historically foreshadowed negative returns relative to value.

For example, US growth stocks currently trade at 52x their cyclically-adjusted historical earnings (CAPE) compared to 21x for value stocks. That’s the most expensive they’ve been in relative terms since the dotcom bubble in 2000.

Note that the same argument couldn’t have been made five years ago, let alone ten years ago. In both 2016 and 2011, growth stocks were trading at a significantly lower premium to value stocks.

Yet valuations are far less supportive today. This means the odds of a sustained value rally are far greater than ever before.

The worst is probably behind us

Rising bond yields and growth expectations may have been the catalyst for the recent rotation into value. But history suggests that these correlations do not always persist.

The turnover and changes in composition of the value and growth indices over time means that their overall relationship with interest rates varies.

The speed of changes in the macroeconomic environment as well as the relative cyclical exposure of value and growth stocks may be important drivers of returns.

The main implication of this is that higher interest rates and economic growth may not be required for a reversal in value’s long-term fortunes.

Arguably, the price investors pay is a more reliable indicator for future returns. Given the relatively wide premium at which growth stocks currently trade, the odds are increasingly stacked against them over the coming decade.

Stay up to date with all our latest news

Hit the 'follow' button below and you'll be notified every time we post content on Livewire. To learn more about our capabilities, please visit our website.

1 topic