What return can you expect from Australian equities?

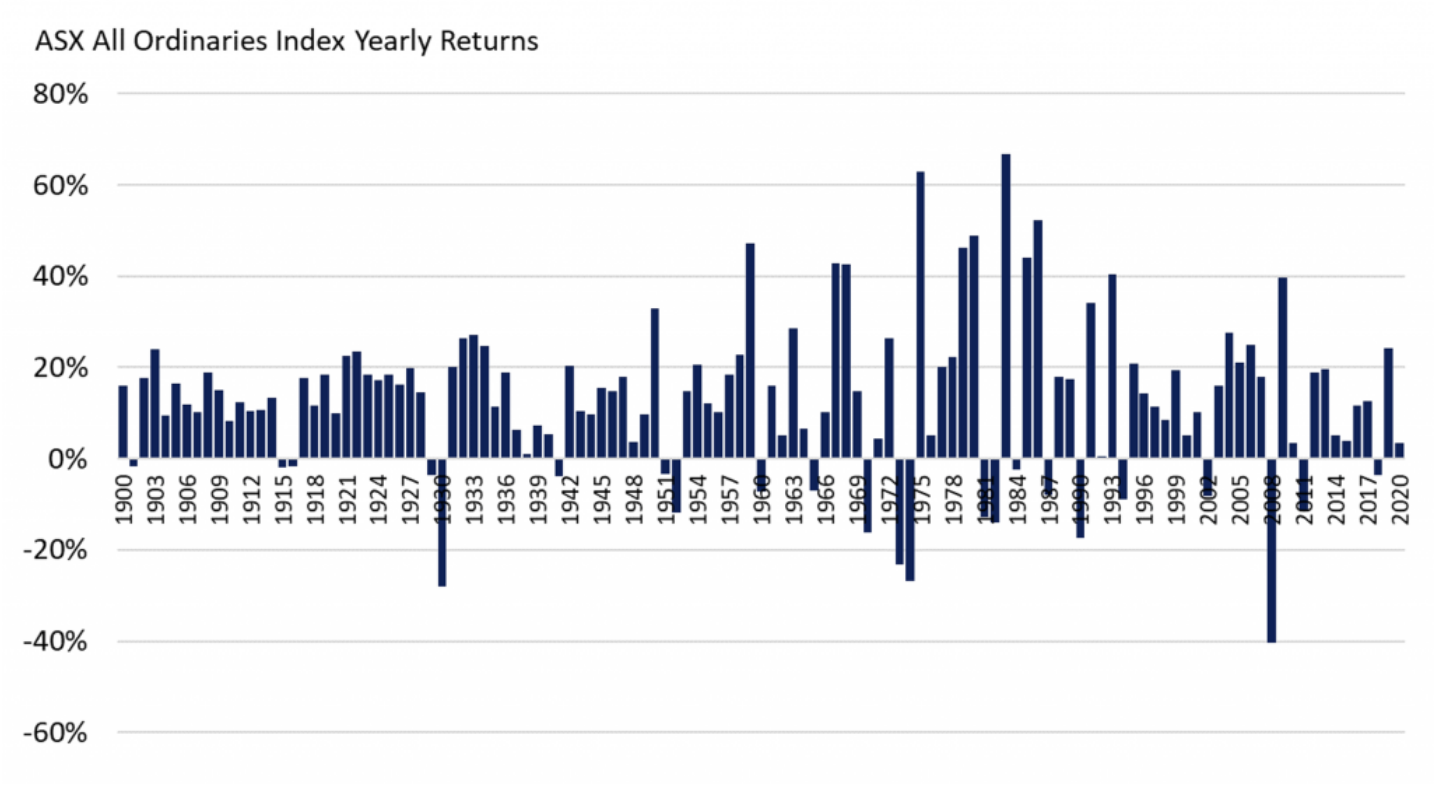

Equities, while volatile, have historically provided attractive returns to long-term investors. The ASX All Ordinaries Index, for example, has delivered a compound total return (capital growth plus dividends) in the region of 12% per annum since 1900.

It is worth noting here that we are probably more interested in the “real” return (or return after inflation) and should be wary of comparing high-inflation periods with low-inflation periods. If we look at the last three decades (sidestepping the high-inflation period of the 1980s) the total return has been around 10% p.a., and more recently the return has been a little lower still (although shorter timeframes are naturally more variable). The full history of ASX All Ordinaries returns is set out below.

Source: Marketindex.com.au

There are, of course, some wild swings from year to year, but with compound average returns at these sorts of levels it has made a lot of sense for investors to be invested in equities and to hang on through the inevitable, and unpredictable, tough periods.

However, past performance, as they say, is no guarantee of future performance, and it is prudent to consider whether the investment math of past decades is as valid today. In particular, it is worth noting that valuations play a significant part in determining future returns and that the return on a share bought at a time of cheap valuations will likely be higher than the return on a share bought at a time of higher valuations. To illustrate the difference, an investor who bought the All Ordinaries at the start of 2008 and held for ten years would have achieved a total return of just 4% p.a., while an investor who bought at the start of 2009 and held for ten years would have achieved a total return of 9% p.a.

One way of digging a bit further into the question of future returns is to consider separately two components of total return: the current dividend yield, and future growth. Let’s start with current dividend yield.

Estimating Dividend Yield

For many stocks it is not hard to arrive at a reasonable estimate of dividends, say, one year into the future, and by aggregating broker forecasts we can obtain an estimate of the expected yield from the S&P/ASX200 Index, which at the time of writing stands at around 3.6%. It is tempting to compare this yield with historical averages to determine whether the current market may look cheap or expensive on a relative basis, but there are some potential problems with this, including the fact that a significant contribution to forward dividends today comes from big mining companies which are enjoying record (and potentially unsustainable) commodity prices. To arrive at a less noisy measure, we might select from the largest ASX-listed companies a sample of some different businesses with a reasonably stable earnings profile, and which are not currently experiencing either boom times or severe COVID-19 depression. For this exercise, we’ll use CBA, CSL, MQG, WOW, TLS, and GMG.

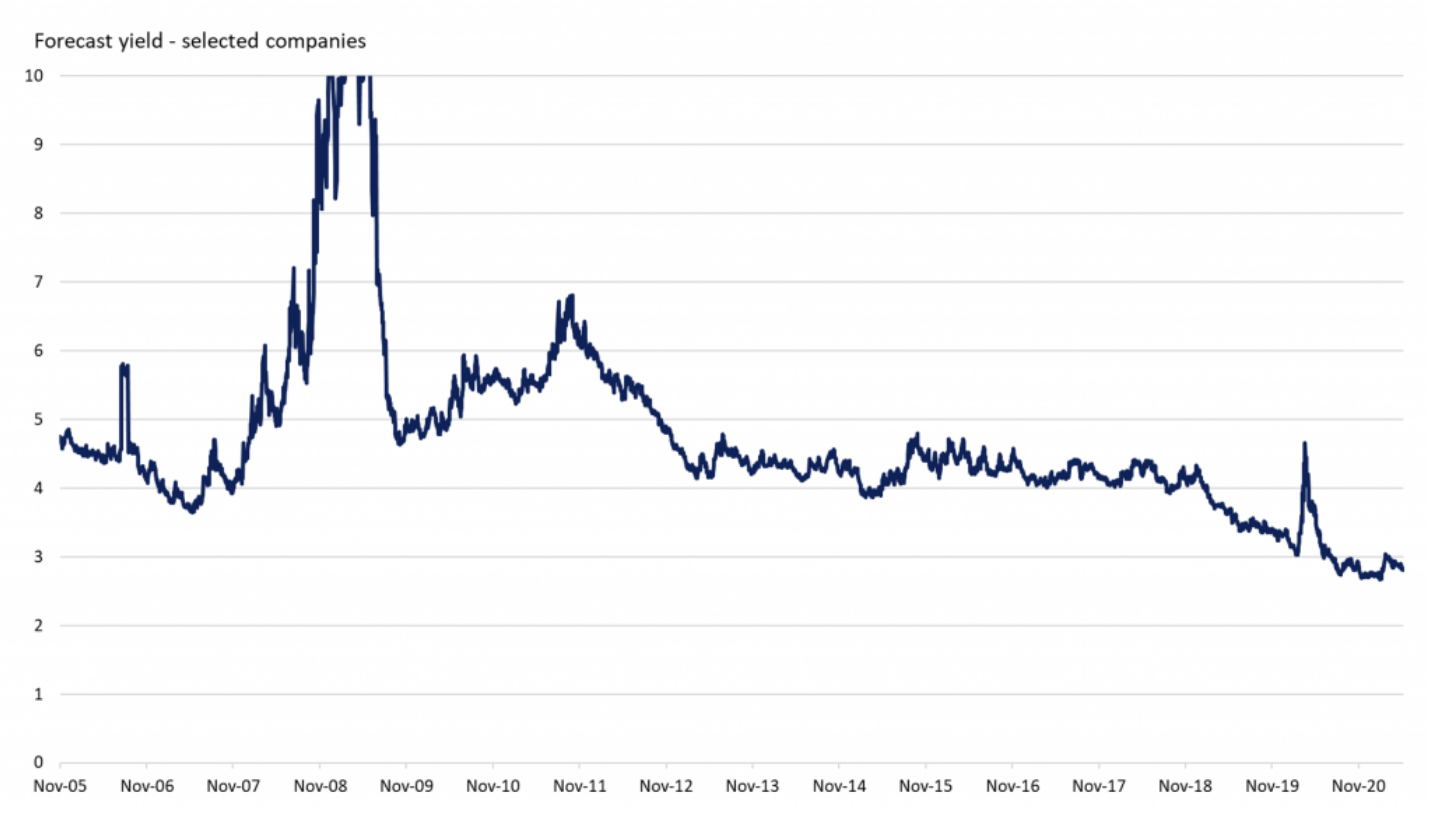

If we take the average forecast dividend yield on this group of companies and compare this forecast yield with its 15-year history, we see the results set out below:

Source: Bloomberg, MIM analysis

The first thing that stands out from the chart is a dramatic rise in forecast yield during the GFC. This happened as share prices plummeted more quickly than forecasts were revised, and broker forecasts became detached from the reality of market expectations. Forecasts caught up with market expectations in 2009 and so the data either side of the spike is probably reasonable, but the spike itself is perhaps best ignored. A similar (but much more contained) spike occurred in early 2020 as COVID-19 rocked the market.

The next thing that falls out of the chart is that the dividend yield on our basket of stocks is currently lower than it has been at any time in our available history. Against a typical historical level of between 4% and 5%, the current dividend yield of 2.8% looks a little slender, around 1.5% – 2% below past levels.

It is worth noting that this is the expected dividend yield on our particular basket of stocks, not the market as a whole, but it turns out that the historical dividend yield of 4-5% on our basket aligns quite well with the historical dividend yield for the overall market, so our group of stocks is probably somewhat representative. As a corollary, the yield for the broader market today (if we were to look through short-term effects like elevated commodity prices) may be in the order of 1.5– 2.0% below its average of the past decade or two.

Future Growth

If we accept 2.8% as a measure of current dividend yield and turn to the growth component of total return, there are several ways we might proceed. For an investor looking to sell in the foreseeable future, the most relevant growth term is the change in share price from today to the time of sale. Unfortunately, however, forecasting near-term changes in share prices is far more difficult than many people realise. And when I say far more difficult, what I mean is that for practical purposes its essentially impossible.

However, if we take the view of a long-term investor, the growth component of total return becomes much more tractable. For an investor who does not intend to sell their equities, the growth component of total return comes in the form of the long-term rate of dividend growth. This is something we can more readily estimate by reference to historical growth rates.

In looking at historical growth rates, we again want to be wary of inflation, and so focus on more recent history, and we should also acknowledge that there is as much art as science in selecting an estimate for long-term future rates of dividend growth based on history. Having said that, an estimate in the region of 5% p.a. which is reasonably consistent with recent history for the ASX (and also consistent with nominal Australian GDP growth) might be a fair place to start.

5% p.a. dividend growth bring us to an estimated total return in the region of 7.5 to 8.0% p.a. for a long-term equity investor buying the market today. This is somewhat lower than the returns earned in years gone by, but in a world where interest rates and inflation may stay at low levels for some time to come, this might be seen as relatively attractive, particularly having regard to the alternatives, including a return on cash in the region of zero.

Some Observations

There are parts of the equity market that currently trade on eye-watering multiples, particularly some of the high-growth names, and in my view, there are some legitimate concerns around the sustainability of these valuations (even after some recent pullbacks). However, in looking at the market more broadly, it is possible to make a case that valuations are not unreasonable, provided interest rates and inflation remain subdued for an extended period. While forward returns look low by historical norms, they need to be viewed in the context of the available alternatives.

If inflation and interest rates surprise on the upside, there is certainly scope for markets to perform poorly, but this is nothing new: markets have always had the potential to perform poorly due to both foreseeable and unforeseeable risks, and it makes sense for most investors to accept this risk in return for a good long-term outcome.

So, while potential future equity returns do not seem as rosy as they might have in years past, and cautious investors may wish to retain some cash on the sidelines, remaining substantially invested in the market today seems – as it usually does – a sensible position for a long-term investor to adopt.

Never miss an insight

Enjoy this wire? Hit the ‘like’ button to let us know. Stay up to date with my content by hitting the ‘follow’ button below and you’ll be notified every time I post a wire.

Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

5 topics

6 stocks mentioned