What's happening in commodities?

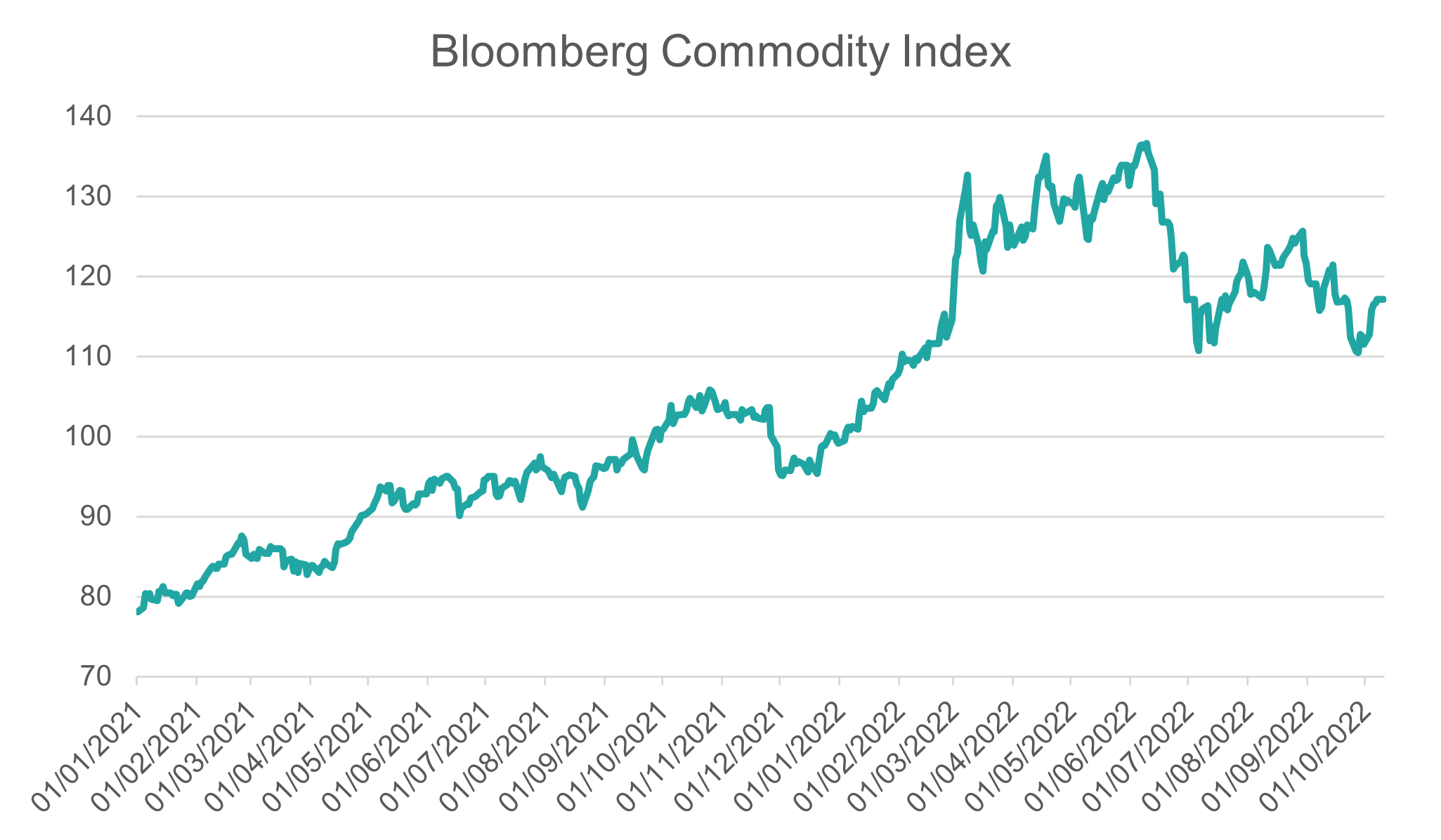

At one point in 2022, commodities were the only asset class which was positive YTD – as a completely unconstrainted investor, the returns for all H1 2022 were to be found in commodities and holding US dollars.

Between supply chain disruptions skyrocketing the demand for semiconductors (and associated rare earth metals), the Russia/Ukraine conflict limiting the export of agricultural commodities and the European energy crisis, there seemed to be no end to the tailwinds for a broad commodity exposure.

Investors who got wind of this dynamic during 2021 found themselves in outstanding risk-adjusted positions, with even the hedge fund community all ceding that commodities were the play of the moment.

However, for those who became enthralled by the positive returns and ragingly positive sentiment in mid-2022, their returns to date are far less outstanding. Since the Bloomberg Commodity Index peaked in June 2022, we are down -14.25% from the highs, whilst at its deepest the decline was nearly 20%.

This shift in fortunes may have many investors asking, “what’s happening in commodities?” – a question we’ll endeavour to shed some light on today.

Precious metals

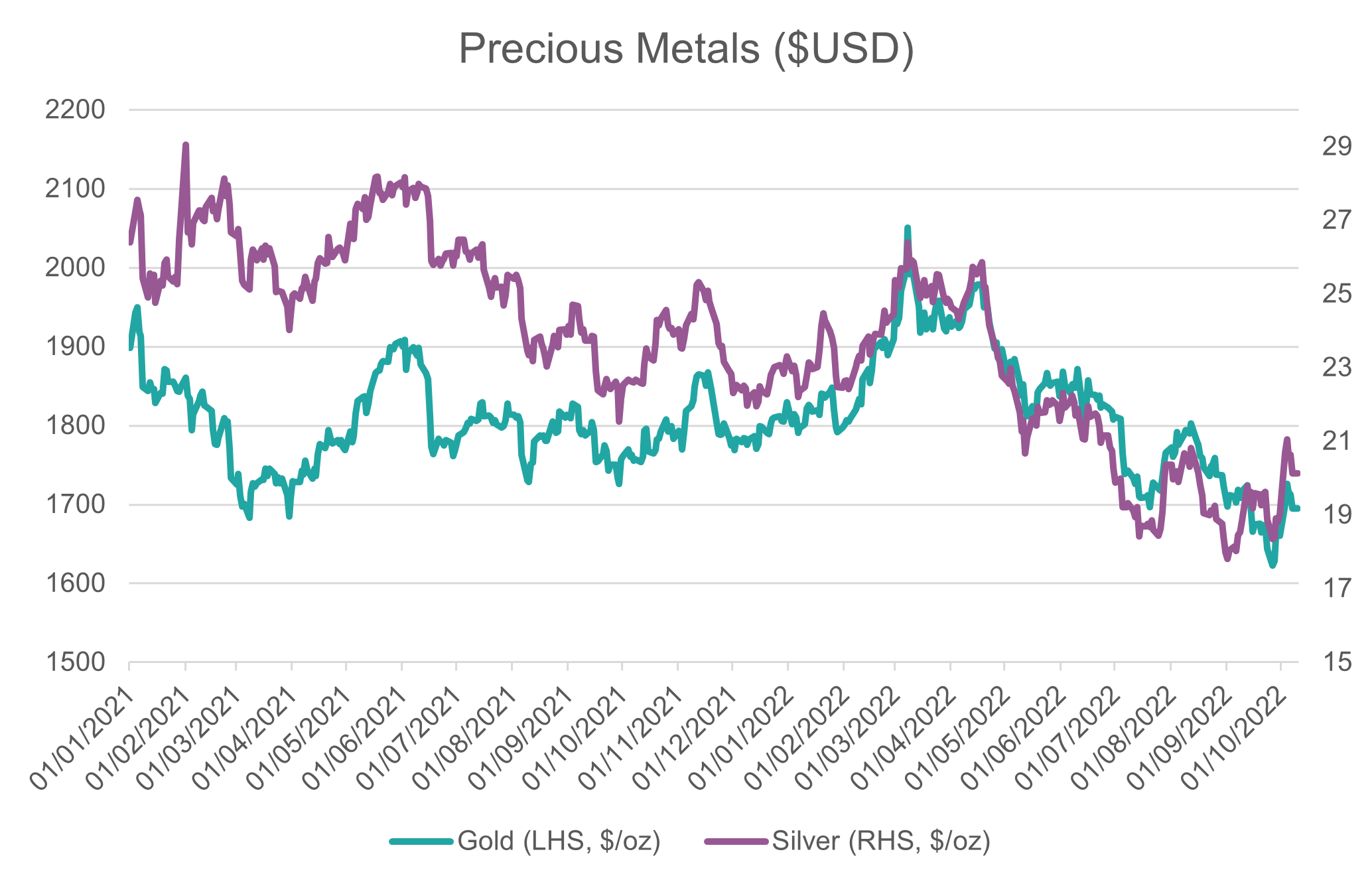

Precious metals, particularly gold, have had the significant headwinds of a raging US dollar and rising yields since around April 2022. Whilst gold tends to be buoyant in an environment of a weak USD, negative real yields and dubious monetary policy, the opposite is true when central banks make a global effort to tighten their belts and tame inflation.

Despite the disappointing performance over the past six months, precious metals may have a more positive outlook than it would seem from the outset; the price of gold is increasingly being viewed as “cheap”, long gold is a compelling way of expressing a view that the USD has topped, and any signal that other central banks will follow the BOE’s restarting of QE measures should benefit “stores of value” assets like gold.

If we look at an expert (albeit biased) opinion - Tom Palmer, CEO of Newmont (the largest gold producer in the world) saw the gold price ranging between $1,900-2,000 for the next few years, as a combination of geopolitical uncertainty and fundamental tailwinds help support the price. Since that interview the price has fallen from $1,850 to $1,700, however Palmer did stipulate that he saw a new price floor forming around $1,600 as the Ukraine conflict and the fallout from a decade of loose monetary policy kept investors uncertain, and in need of a “safe haven” such as gold.

Industrial metals

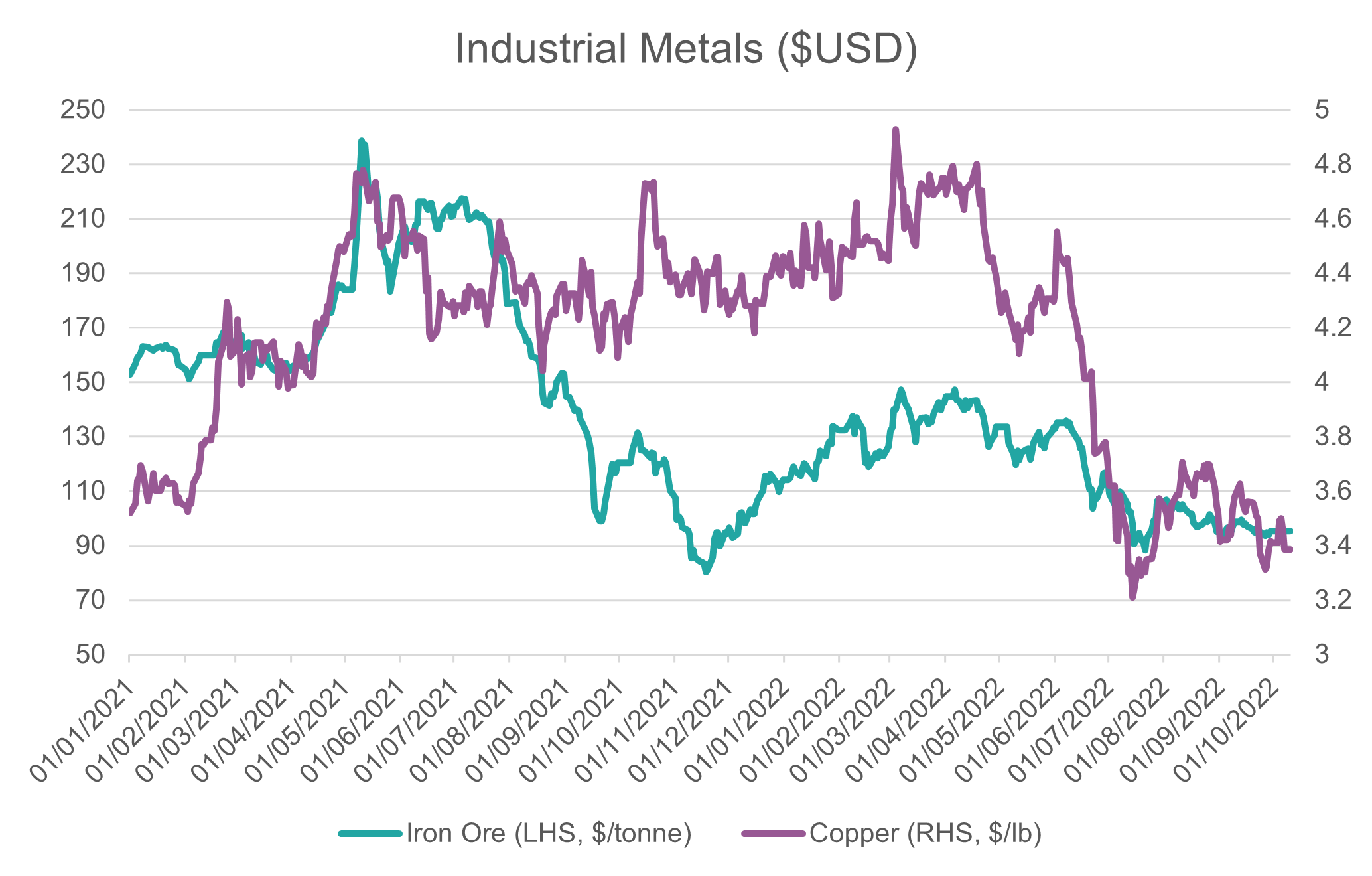

Industrial metals are highly subject to levels of aggregate demand within the global economy – there’s a reason why copper is called the “metal with an economics degree”.

It’s perhaps unsurprising then that copper and iron ore have had uninspired performance in recent history – iron ore has been in the doldrums since it became apparent that lockdowns in China were not a transitory phenomenon, and copper followed suit as the reality that central banks would likely hike us into a global recession set in.

Not to exclude other major resources importers, such as India, the potential for a rebound in these metals likely rests with a surprise growth outlook from China.

The National Party Congress on the 16 October represents an opportunity for this exact surprise, where there is already evidence that there is significant investment occurring in China behind the swathes of poor economic data. If there is some path to re-opening and economic stimulus, then industrial metals (and associated assets, such as the Aussie dollar) stand to make a comeback – however if the 16 October reveals continued lockdowns, the outlook may be depressed for some time.

Something to amplify this situation is that iron ore producers, such as Vale, were slicing their full-year production forecasts back in July, which may not affect markets much if global demand continues to fall but may leave a supply shortage in the marketplace if a China demand shock comes along.

Energy

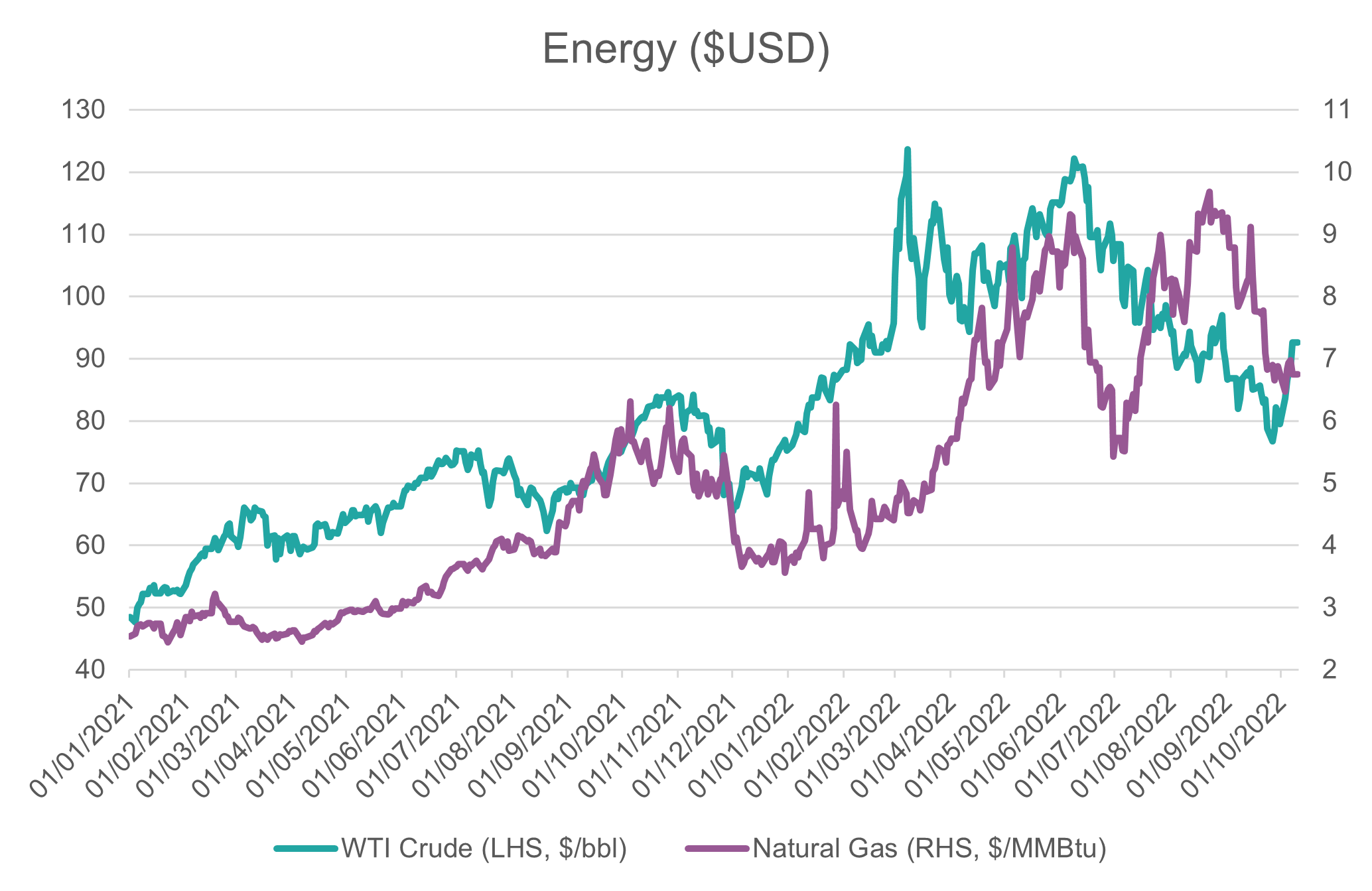

Starting the year with a Russia/Ukraine conflict, after there were already concerns around a European energy crisis in Q3 2021, certainly lent itself to a rally in energy commodities.

Recent news items have dampened this aggressive rally, which doubtless had some contribution from euphoric sentiment and TINA (there is no alternative) attitudes by many market actors all crowding into the same positions. As news came out that Germany and other European nations had filled reserves to around ~80% of target well ahead of time, much of this sentiment spilled out of the market

Regardless of the short-term volatility, the removal of cheap Russian energy to Europe and the subsequent revelation that they were massively vulnerable to external supplies is likely to keep energy commodities rising into the future.

The decarbonisation movement will grow alongside this newfound reliance on hydrocarbons. However, a combination of very little exploration and development of fossil fuel assets, as well as countries looking to protect their own domestic reserves, will mean many players are competing for relatively limited supplies of energy commodities.

For the short-term, it’s likely that energy assets continue to be more subdued than they were 3-6 months ago, as growing levels of demand destruction at the hands of monetary policy weights down the appetite for oil and natural gas.

One interesting headwind/tailwind (respectively) is that a September IEA report, which noted that a largescale transition from natural gas to oil, around 700 kb/d (thousand barrels per day) during Q4 2022 and Q1 2023 – although this doesn’t change the macro picture, it does suggest there are changing dynamics in traditional uses of fossil fuels which could make this space more volatile but hold the potential for “winners versus losers”.

A scarce commodity

As such a broad and complex asset class, commodities are an area where active management within a diversified portfolio is overwhelmingly the appropriate choice for a non-expert investor.

Our view remains that the macro landscape is volatile and uncertain, with no clear signs those qualities will change throughout the remainder of this year.

As global demand outlooks continue to deteriorate, there may be further fluctuations within commodities which are sensitive to anything from manufacturing, home building, travel and so on – as we consider a commodity allocation on a strategic timeframe however, the geopolitical uncertainty of 2022 is likely to create a rising sense of resource nationalisation/taxation which could restrict supply and drive prices up over the long term.

5 topics