What’s so special about the next interest rate cycle?

One of the advantages claimed by investors in more credit-oriented portfolios is that credit returns often provide partial protection against rising interest rates. Though this relationship often holds true there are reasons for being cautious about its ability to provide protection as interest rates rise in this cycle.

Aside from the higher return available from credit, the basic premise is that interest rates and credit spreads should be negatively correlated; i.e. credit spreads should act as a partial buffer for movements in interest rates over the cycle. The existence of such a relationship is based on the traditional view of the economic cycle where it would be expected that a negative relationship between shorter term interest rates and credit spreads exists. The reference to shorter term interest rates is important as the shorter end of the curve should be pricing in market expectations regarding economic growth and monetary policy and hence reflect similar fundamentals to credit spreads. Why should such a relationship be expected?

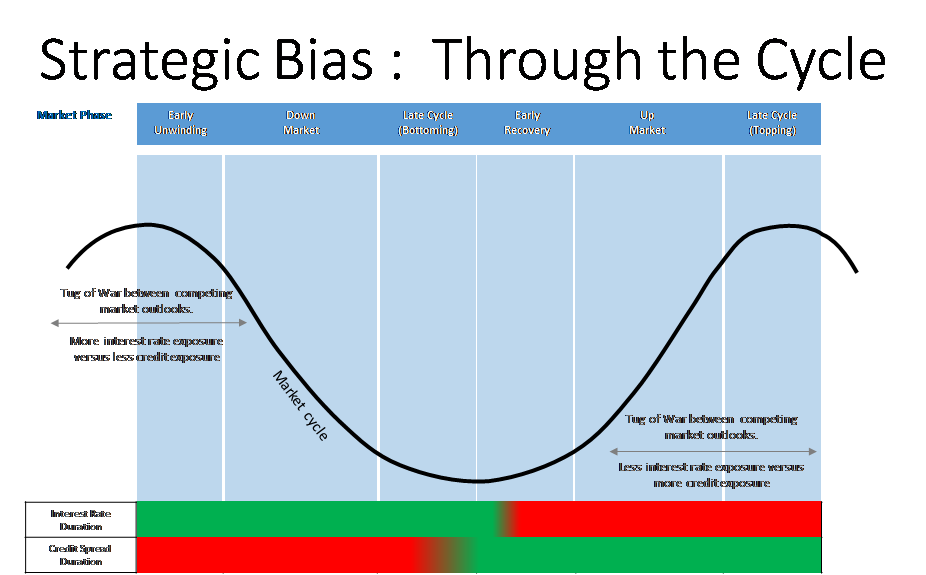

Chart 1 :Strategic bias through the cycle

The key to the existence of the relationship is the link between monetary policy and the economic cycle. As maintaining economic stability is part of most central banks objectives there will be a tendency for central banks to manage monetary policy to “lean” against the cycle. Given such a bias, over an economic cycle, increasing short-term bond rates signal that it is expected that central banks will be raising rates which is indicative of stronger expected economic conditions and hence positively impacts the fundamentals for corporations and credit spreads; i.e. credit spreads contract as interest rates rise. The opposite holds for declining short-term bond rates which in turn signal that central banks are more likely to be reducing interest rates in response to deteriorating economic growth and hence are negative for credit spreads; i.e. credit spreads expand as interest rates decline. The result of this tendency for central banks to “lean” against the economic cycle is the generation a negative relationship between interest rates and credit spreads over a traditional economic cycle.

While such a relationship sounds good in theory, in practice are credit spreads linked to shorter dated interest rates? Skipping through detailed statistical analysis it is simplest to say “Yes”. Undertaking statistical analysis, using data from Oct 1999-April 2018 for both Australian investment grade credit and hybrids (proxy for Australian high yield), highlights that significant negative correlations do exist between the returns on shorter term interest rates and credit portfolios with the same underlying interest rate duration. What is potentially of most interest to credit oriented investors is that the negative relationship has become materially stronger post the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 (“GFC”). Isn’t a stronger negative relationship between the returns derived from interest rates and those derived from credit spreads a good thing for investors in credit? Maybe, but not necessarily. To see why consider that there are two possible explanations for the stronger negative relationship post GFC.

The first is that the stronger relationship post GFC aligns with the traditional relationship based on the economic cycle which was outlined earlier. The difference is that only now market expectations regarding central bank monetary policy may have become a more significant barometer for investors seeking to interpret the pace and sustainability of improvements in economic growth and corporate fundamentals. If this is the case, as central banks raise rates in the future, an investor could continue to anticipate a negative correlation between the returns generated by interest rate and credit spread movements; i.e. credit will continue to act as a partial buffer against movements in interest rates.

Of potential concern to investors in credit is an alternative, non-traditional, relationship which implies that the drivers of the linkage between interest rates and credit spreads may have changed. The catalyst for such a change in drivers may be the more explicit targeting by central banks of stability within the financial markets themselves as a means of managing the economic cycle. With stability in financial markets a more explicit target, monetary policy may increasingly be used to offset episodes of heightened risk aversion. To more clearly illustrate the difference in dynamics, under the traditional model declining interest rates signal an expectation of slower growth and hence credit spreads increased. Under the alternative model it is the increase in credit spreads themselves, arising from heightened risk aversion amongst investors, which central banks are seeking to offset with lower interest rates. So, while the statistical relationship between interest rates and credit spreads is the same the interlinkage is materially different.

While either argument can serve as an explanation of the stronger negative relationship to date, as the interlinkages are different, they have very different implications for credit spreads as central banks exit a period of highly accommodative monetary policy. Critically under the non-traditional relationship movements in credit spreads are no longer simply a by-product of the central banks use of monetary policy to “lean” against the traditional economic cycle. Rather credit spreads have been used directly by central banks as a specific target of monetary policy and a lever by which to implement and maintain accommodative monetary policy. With lower credit spreads being a specific target of accommodative monetary policy then, less accommodative monetary policy is likely to deliver both rising credit spreads and interest rates. If this is the case, then investors may well find that as central banks raise rates the interlinkage between credit and interest rate cycles will differ materially from what would traditionally be expected.

1 topic

Clive Smith is an investment professional with over 35 years experience at a senior level across domestic and global public and private fixed income markets. Clive holds a Bachelor of Economics, Master of Economics and Master of Applied Finance...

Expertise

Clive Smith is an investment professional with over 35 years experience at a senior level across domestic and global public and private fixed income markets. Clive holds a Bachelor of Economics, Master of Economics and Master of Applied Finance...