What the Federal Budget means for the RBA and your investments

Key budget measures

- $5.4 billion in a broader round of cost-of-living relief, including broadening energy bill relief for all households and extending rent assistance.

- A renewed focus on the benefits to all households from the Stage 3 tax cuts that were rejigged in January (worth an average of $36/wk).

- $3 billion for community pharmacies for cheaper medication and $6.2 billion on Medicare and expanding the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

- $9.6 billion on housing and crisis accommodation and extra on related infrastructure (although much is a continuation of existing programs) and $89 million to train home builders (although the planned 20,000 new tradies are only 1.7% of the existing construction workforce).

- Prac payments for nurses, midwives and social workers.

- A change to student debt indexation which cuts the value of debt with no near-term budget cost as it won’t involve a handout to students.

- A mix of subsidies, tax breaks, cheap loans, relaxed foreign investment rules & less red tape to boost investment in government-chosen industries as part of the $22.7 billion “FMIA” policy.

- Caps on international student arrivals by each university which can be raised if they build more student accommodation.

- Extra spending on aged care & childcare to cover wage rises.

- Freeze on deeming rates for low-income households.

Budget savings include:

- Further savings in areas like consultants, compliance and efficiencies and reducing spending on the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

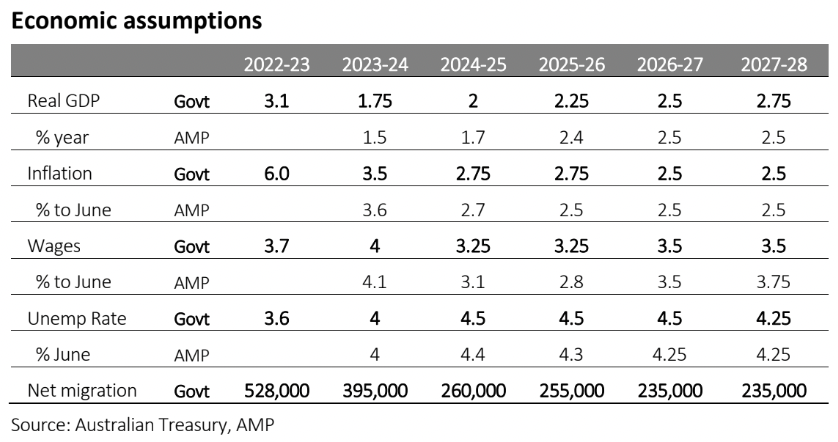

Economic assumptions

The Government now sees net immigration of 395,000 this financial year (MYEFO was 375,000), falling to 260,000 in 2024-25, taking population growth down to around 1.4% from 2.4% in 2022-23. The Government kept its medium-term iron ore price assumption at $US60/tonne. With the iron ore price well above that (>$US100 as of May 2024), it’s still a potential source of revenue upside.

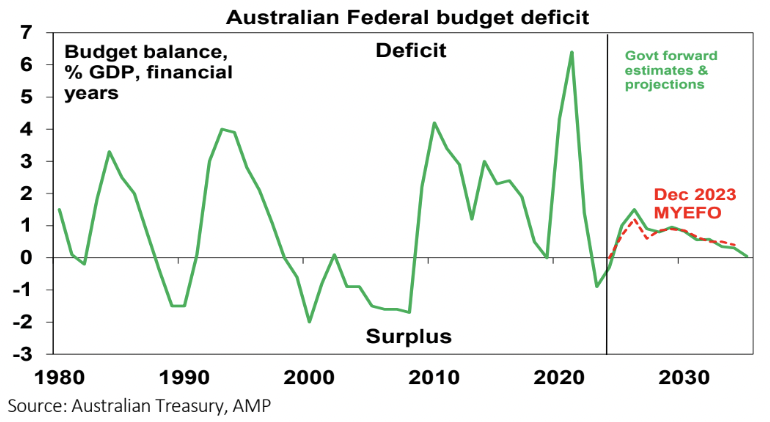

Another budget surplus then bigger deficits

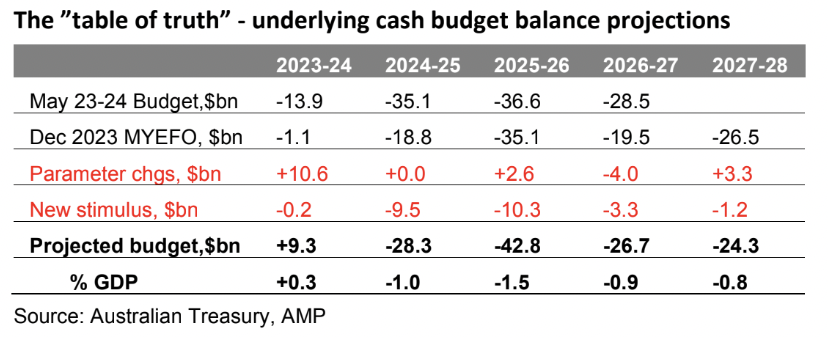

This windfall (see the line called “parameter changes” in the next table) is estimated to reduce the deficit in this financial year by $10.6 billion compared to last December’s update, with a total benefit over the five years shown of $12.6 billion. But this table – a more detailed version of which appears in the Budget papers and is nicknamed the “table of truth” – also shows how much of the windfall has been spent (see the line called “new stimulus”).

Last year, only 14% of the windfall through the forward years was spent but this budget nearly twice the windfall (i.e. $24.4 billion) is being spent. As a result, while the budget now looks better for this financial year (with another surplus – which could turn out to be even bigger), because of the extra spending in subsequent years it now looks worse from 2024-25.

After a surplus this year, there are bigger deficits over the next few years. Gross public debt is projected to remain elevated at around 35% of GDP before falling next decade.

Winners and losers

Losers include consultants, universities, foreign students, backpackers and dodgy NDIS providers.

Assessment

However, the Budget has several significant weaknesses around:

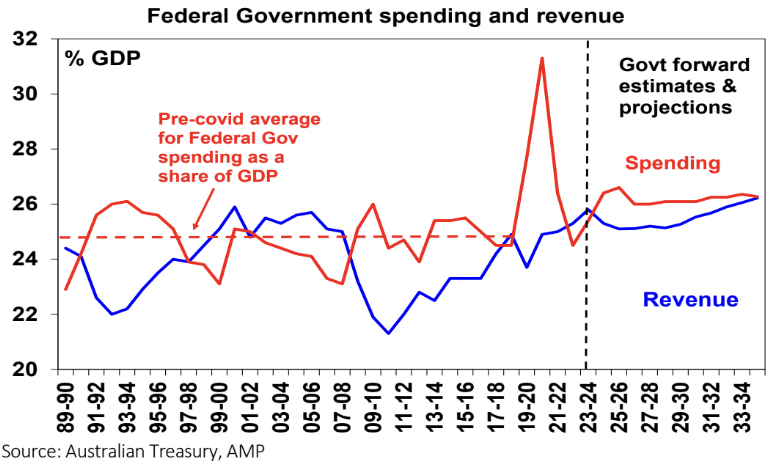

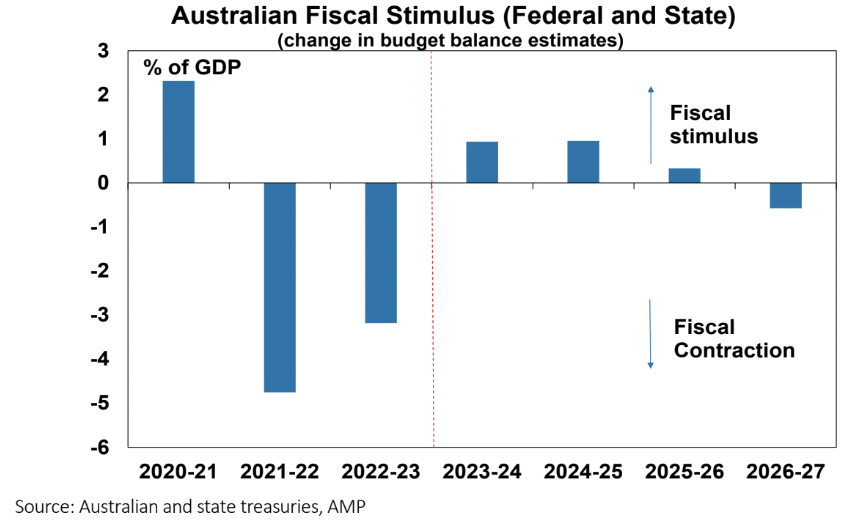

- Inflation: The cost-of-living measures will help lower measured inflation. However, the new stimulus (shown in the “table of truth” above) risks boosting demand. Federal and state fiscal positions point to a sharp shift from fiscal contraction (which helps lower demand and inflation) to expansion over the year ahead (see the next chart). Government support for high wage increases for some sectors risks adding to wage growth given the flow on and influencing effects at a time when wage growth is already at its maximum level consistent with the inflation target. All of which risks making the RBA’s job harder.

- Structural deficits: The Budget has added to medium-term structural deficits. This leaves it vulnerable if the economy weakens and sees no money put aside for a rainy day over the forecast period.

- Bigger government: Spending as a share of GDP is seen settling well above that seen pre-pandemic thereby locking in a bigger government sector which risks further slowing medium-term productivity growth.

- FMIA: While “Made in Australia” is popular and there is talk of a “new growth” model, its reliance on protectionism and government picking winners has been tried and failed in the past with a long-term cost to productivity and living standards. Moving to net zero is one thing, but this doesn’t mean we need to make solar panels or quantum computing or that we have a comparative advantage in them. Just because other countries are deploying subsidies is no reason for Australia to do so. We should just take the subsidised products!

- Productivity: Beyond the hopes of FMIA, there is not a lot here to improve Australia’s medium-term productivity performance. This is the key to growth in living standards but needs urgent reform in terms of tax, competition, the non-market services sector, industrial relations, education and training and energy generation. Fortunately, the Government is moving on the last two at least.

- Housing: The latest housing measures are welcome, but are unlikely to be enough to hit the 1.2 million new homes over five years objective with the supply shortfall set to remain unless immigration plunges.