What the RBA's house price forecasts might look like...

A critical influence on our housing market predictions has been the Reserve Bank of Australia’s innovative research on the subject, exemplified by the pioneering 2019 housing model developed by Peter Tulip and Trent Saunders.

Tulip and Saunders controversially concluded that reductions in interest rates, rather than inelastic supply or/or population growth, explained most of the rise in house prices over the last big boom between 2013 and 2017.

The co-authors noted, however, that this was just the monetary policy transmission mechanism in practice, observing that “a large part of the effect of interest rates on dwelling investment, and hence GDP, works through housing prices”.

(Tulip is now chief economist at the Centre for Independent Studies while Saunders is Principal Economist at the Queensland Treasury Corporation.)

Our chief macro strategist, Kieran Davies, who was previously a principal adviser on the macroeconomy at the Commonwealth Treasury, has spent considerable time updating and re-estimating the model that underpins this RBA research.

This is an important exercise because the Saunders-Tulip model is used by Martin Place to better understand the relationships between interest rates, residential investment, rents and house prices.

“We’ve used this RBA model to calculate internally-consistent forecasts that allow for feedback between quantities and prices,” Davies comments. “The RBA’s model contrasts with the usual academic approach of estimating house prices using a single equation, furnishing richer detail on the housing market than the central bank’s own MARTIN macroeconomic model.”

The Saunders-Tulip model embeds a long-run relationship between real house prices and the ratio of real rents to the “user cost of housing”, where the latter captures the cost of owning a home (i.e., interest payments and running costs less expected capital appreciation). This means that dwelling values adjust over the long term to keep the cost of owning a home close to the cost of renting.

In the short term, the model allows for a gradual adjustment of house prices to this long-run equilibrium, including momentum in these prices and the short-run impact of real interest rates.

“In estimating the Saunders-Tulip model, some inputs, such as household income, working-age population and inflation, are driven by past trends, while the unemployment rate is determined by an Okun’s Law relationship with income,” Davies explains.

“In using the model to forecast house prices, we overwrote these estimates with forecasts from the RBA’s latest Statement on Monetary Policy and the Commonwealth’s budget update. Interest rates were based on market pricing prevailing at the end of last year, when the curve was near zero out to three years.”

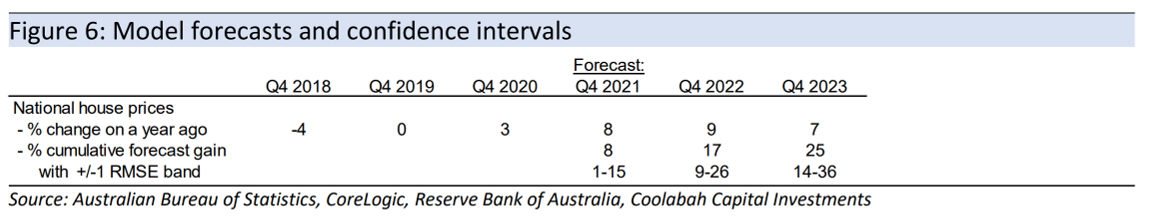

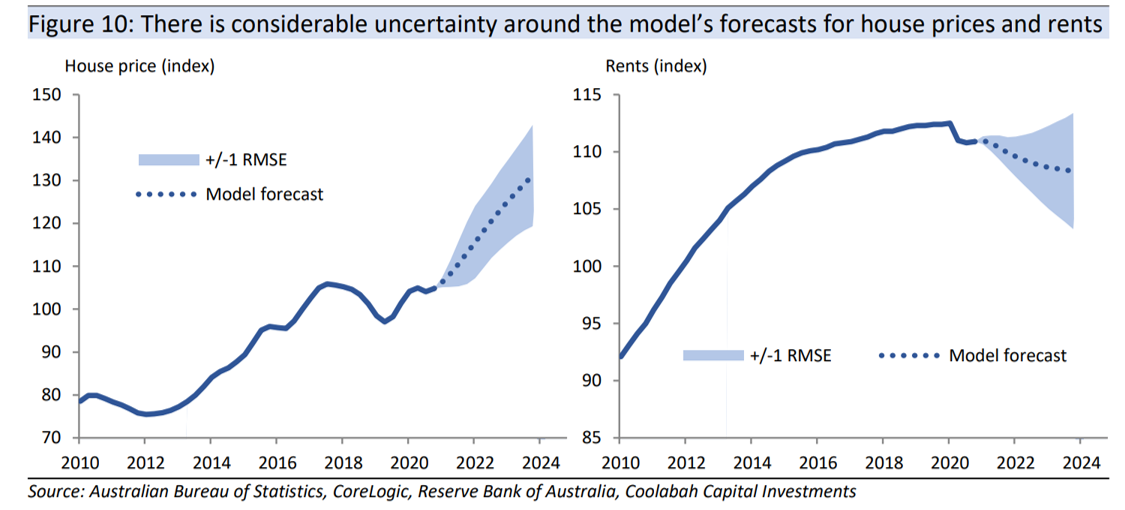

The key finding is, unsurprisingly, a central case encompassing a 25 per cent increase in nominal Australian house prices between December 2020 and December 2023 with a confidence interval spanning 14 per cent through to 36 per cent.

This is very similar to our prevailing official forecast anticipating cumulative capital gains of 20 per cent to 30 per cent over the two to three years after the last housing peak in April 2020.

The RBA’s model also points to much stronger residential construction, with investment projected to increase by 26 per cent over three years, albeit that much of this materialises in 2021.

The housing boom, which has boosted consumer and business confidence, and investment intentions, is a direct result of the record fiscal and monetary stimulus that is seeking to ensure that the spike in excess labour market capacity wrought by COVID-19 can be fully utilised as quickly as possible. (The longer folks remain unemployed, the harder it is to get a job.)

This is why it is also a global phenomenon: Davies finds that house prices have increased in almost every advanced economy (23 of 26) with an average capital gain of 7 per cent in nominal terms from their pre-pandemic levels through to the end of last year.

In his paper on this subject, Davies emphasises three possible risks to this otherwise rosy outlook. “The first is that the closure of the international border has caused the working-age population to stall for the first time in over a century,” he says. “In our analysis, we have assumed that the population will grow in line with Commonwealth government forecasts that show an eventual resumption once the border is gradually re-opened.”

A second uncertainty relates to the role of investors. The Saunders-Tulip model is based on the experience of owner-occupiers, whereas investors account for about 30 per cent of the private sector housing stock. This poses both upside and downside threats to the forecasts.

A third risk relates to lending standards, which are not accounted for by Saunders and Tulip. While credit assessment practices in the banking sector are conservative, any dilution in non-bank and/or bank loan quality will likely result in the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority re-imposing its macro-prudential restrictions on lenders’ decision-making processes.

The emergence of a sustained housing boom will inevitably reignite the affordability and inequality debates. Here Davies comments that although “housing is very affordable as measured by the serviceability of a mortgage given ultra-low interest rates, the time taken to raise a deposit remains a key barrier to entry”.

His analysis shows that it still takes more than two years for a household on an average income to raise the 10 per cent deposit on an average-priced home, which has contributed to reduced ownership rates amongst first timers.

“This is near the maximum time taken to raise a deposit in the past couple of decades, and is likely a factor behind the pronounced trend decline in home ownership rate for the first home-buyer age group,” Davies says. “While the aggregate ownership rate has drifted a little lower, the ageing of the population has mitigated the decline.”

Global empirical research indicates that easy monetary policy actually strongly reduces income inequality by boosting employment and reducing unemployment. Having said that, higher house prices can increase wealth inequality, where inequality is driven by very low home ownership among low-income/resource households.

Interestingly, Davies finds that superannuation, not housing, has been “the largest contributor to the average gain in real wealth per household over the ten years to 2020, adding about 10 percentage points to the 20 per cent increase in total net worth”.

“Housing has been a close second, contributing about 8 percentage points net of mortgages (the family home added about a net 7 percentage points with investment properties adding approximately a net 2 percentage points).”

If the RBA’s monetary policy settings can help ameliorate income inequality by promoting employment and wages growth, concerns about housing affordability and wealth inequality are better addressed by governments through their system of taxes and transfers.

One obvious opportunity that I have been banging on about for almost 20 years is the inflexible supply-side of the housing market, where demand shocks end-up being capitalised into higher prices rather than satiated via the construction of new homes. This supply-side inflexibility is evident from the extremely low price elasticity of the housing stock in Australia, which was first identified by the 2003 prime minister’s home ownership task force report.

Access Coolabah's intellectual edge

With the biggest team in investment-grade Australian fixed-income, Coolabah Capital Investments publishes unique insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid leveraging its 13 analysts and 5 portfolio managers. Click the ‘CONTACT’ button below to get in touch

2 topics