Where the streets have no name

Global Macro

There was much fanfare on the 22nd May 1994 when millionaire Japanese dentist Akihiro Kabe and co-driver Takeshi Okano approached the start of Australia’s inaugural Cannonball run in a $750,000 Ferrari F40. At the time the most expensive new Ferrari in the world, it was about to tackle Darwin to Alice Springs and back, some 4,000 km of roads in the outback of Australia with no speed limit. Having the Ferrari in the event was great coverage, capable of speeds in excess of 300 km/h (185 mph). Who didn’t want to see that?

Halfway through, the Ferrari had lived up to expectations. Averaging over 200 km/h and clocking speeds as high as 300 in the barren outback photographed a treat. Along the rally the drivers had to stop at “checkpoints” to record their progress and to allow the road to be cleared ahead of them. As they rounded a bend at “excessive speed” one such checkpoint came into sight 1 kilometre down the road. And so Kabe tapped on the brakes.

Braking at high speed is notoriously dangerous. It shifts the weight to the front of the car, lightening the rear. The slightest turn or even road contour can then whip the back out to the side, resulting in the notorious fishtail. More braking only exacerbates the tail. And that is where Kabe found himself.

The two men at the post watched on in horror. The Ferrari was fish-tailing and careering off the far side of the road. At “excessive speed”. This was not going to end well. And then just as suddenly, from a hundred meters away, the car fishtailed the other way and in a matter of seconds wiped out the judging post. All four lives were tragically lost.

Speed kills. It also kills economies. And in October we watched the markets “fishtail”.

Will it end in a crash, or will control be regained? Frankly it is too early to say.

Is the road wide enough to cope with a fishtail? Or even a controlled spin? Is there a fatal obstacle that needs to be avoided?

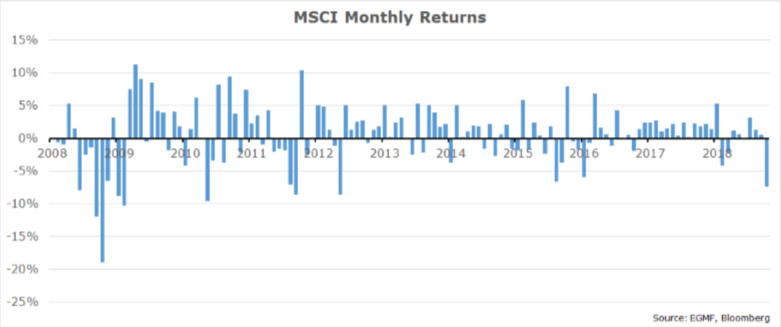

Well I’m afraid the answer is yes, yes and yes. Strong US growth and robust earnings provide a nice wide road. Relatively benign inflation and wages in the US suggest if there is a spin the Fed can pause in their hikes, supporting the economy. But a clash (crash) with China would be catastrophic. What does that mean for the here and now? You have to be flexible and judge the opportunity. Let’s first take stock. October was the worst month for the world share market since 2012.

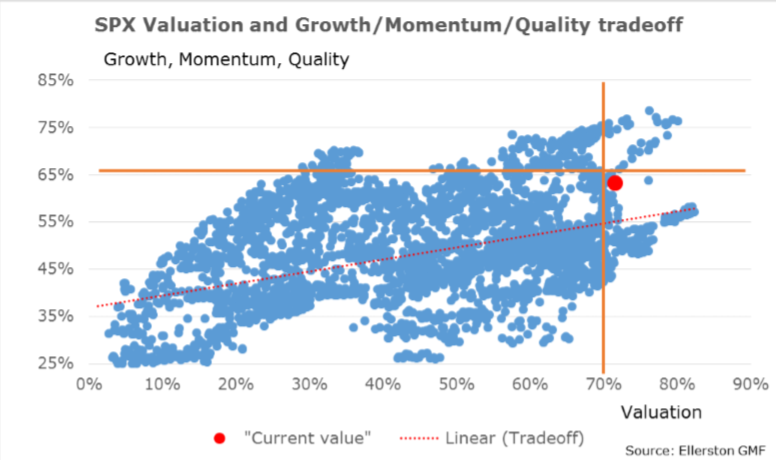

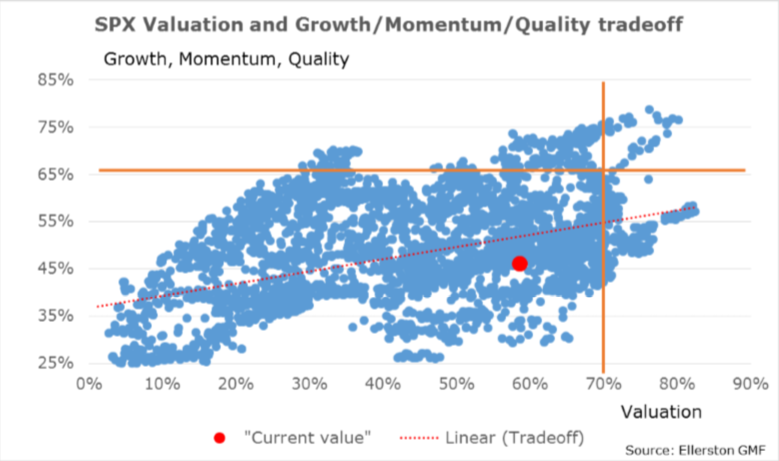

Last month, I wrote about how overvalued the US stock market was on Tim’s metrics. Recall the chart.

I noted overvaluation is not in and of itself a reason to sell the market. It can stay that way for a year or more. But it is vulnerable to a bearish catalyst. And in October it didn’t take much.

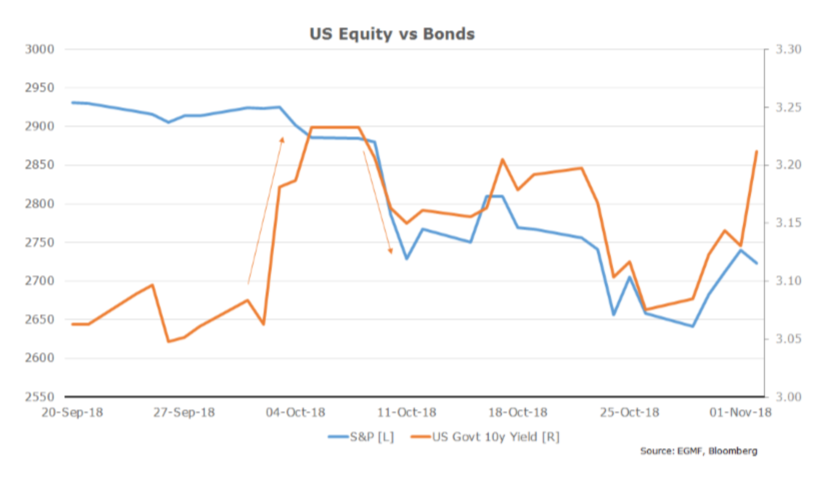

Following a particular strong services PMI on October 3rd, US 10 year bonds jumped to a new high in yield. The S&P wasn’t comfortable, and started to drift lower. Then Powell commented that rates were still a long way from neutral, and stocks capitulated (which in turn dragged yields lower).

Neither of these developments were particularly noteworthy. But the summation of evidence was painting a clear story. Rates are going higher. And once that is accepted, stocks have to adjust to a higher discount factor. After the October move the US stock market is “reasonable” value. But it needs to be cheap to really motivate investors back in.

Or another catalyst. Perhaps a Trump tweet?

Just had a long and very good conversation with President Xi Jinping of China. We talked about many subjects, with a heavy emphasis on Trade. Those discussions are moving along nicely with meetings being scheduled at the G-20 in Argentina. Also had good discussion on North Korea! Maybe the crash between the US and China can be avoided after all? It certainly helped sentiment as we started November.

So that tells you why we are here. But it doesn’t tell you how it ends.

The market outlook

No one has the answer right now. But what I want to do here is give you a framework for understanding what is happening and then at the right time you can extrapolate how it might evolve.

So let’s first identify the main forces we think are driving asset markets.

- The Fed has to manage a slowdown in the economy.

- The cessation of central bank bond purchases, and normalisation of interest rates.

- The China/US battle.

I have written about the Fed’s job at length, so I won’t repeat myself. But understand this simple point. The Fed is forecasting that it will move interest rates to 3.4% (another 5 rate hikes) because it needs to forecast that the US economy slows. In turn, because it needs to forecast that inflation stays near 2%, its mandated target.

Now one can quibble about whether the Fed will need to hike that much to slow the economy, but note very few quibble that the economy needs to slow. The unemployment rate can’t continue falling for ever. Which in turn means the US economy can’t continue growing faster than about 1.8%5 forever. Why not? Because at some point there will be no one left unemployed to hire. Then wages will be bid up to gain employees, and prices will rise to cover that cost. Where is that point? Well as I argued last month, we are already there. Powell is necessarily cautious with his language as Fed Chairman. But past Chairs can, and are, speaking more freely. Greenspan in October on CNBC:

“This is the tightest market, labour market, I’ve ever seen…But concurrently, we have a very slow productivity increase… Ultimately prices take hold.”

And Yellen:

“…at this point it seems to be that at least a couple of more interest rate increases are going to be necessary to stabilize growth at a sustainable pace and stabilize the labour market so that it doesn’t overheat”.

That comment was October 31st, after the stock market had just fallen over 10% in 3 weeks! So make no mistake. The Fed wants this economy to slow.

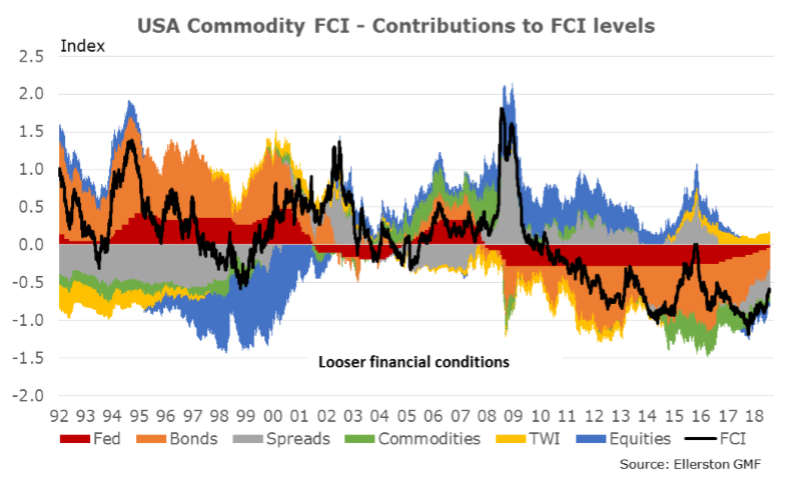

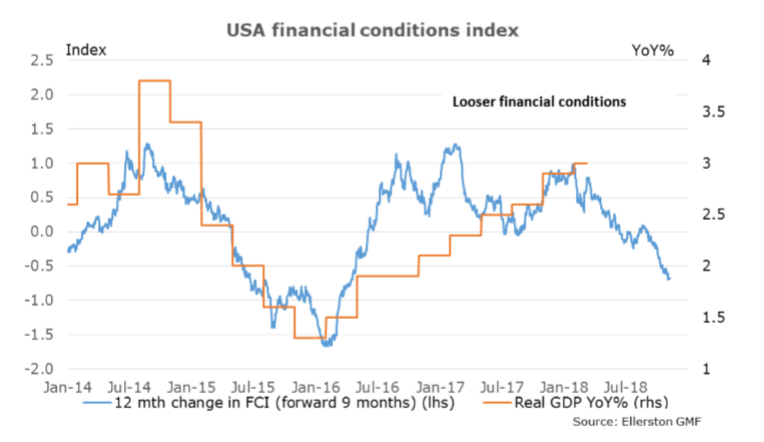

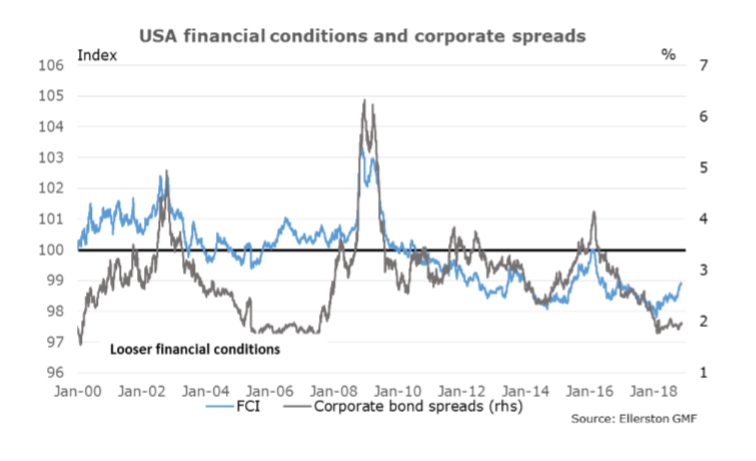

However, where we might make a mistake is what causes it to slow. It doesn’t have to be the Fed. Yellen commented financial conditions remain “accommodative”, or easy, despite the market correction. We agree. Overall financial conditions is what drives an economy. Indeed, it is a key input into every growth forecast we make. So what is it? Financial conditions? We measure it, as do most, in a financial conditions index (FCI). Sure, it includes the overnight interest rate the Fed sets. But it also includes the 30 year mortgage rate. And what rate corporates borrow at. And the “wealth effect” of rising (or falling) stock markets. Even the competitive effect of the currency and commodities.

Key to our process is constructing a financial conditions index that helps us gauge the growth impulse for an economy over the next 9-12 months of all these influences. Right now the level of financial conditions is still “accommodative” as Yellen said, meaning it is supporting growth.

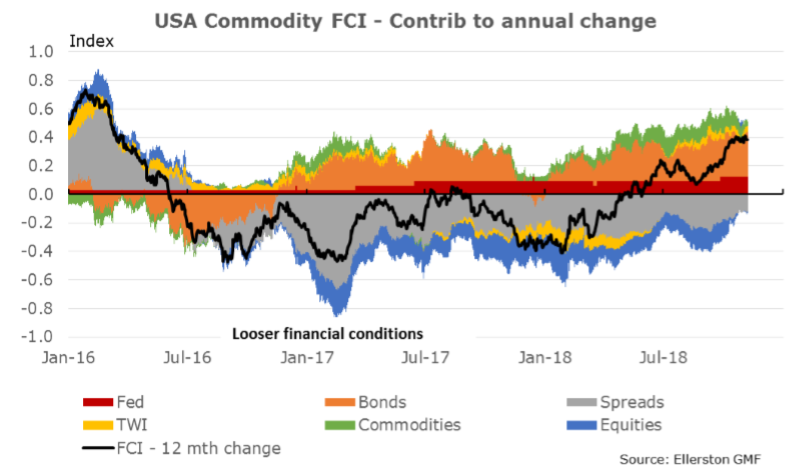

But note that the black line has risen recently. If we chart the change in the FCI over the last 12 months, we can see what is driving that move.

Equities had been contributing to looser financial conditions, and with their recent fall that is no longer the case. Similarly with spreads (which is the spread difference of a corporate bond to a treasury bond, the extra cost to borrow for a corporate). So we can see that less favourable conditions from the US equity market and higher corporate bond spreads have seen the 12 months change in the FCI rise over the last 12 months.

And it is the change in the FCI that drives growth over the next 9-12 months (not level. Level will drive growth beyond the next 12 months).

With the current change, that would suggest US growth will slow to about 2% mid next year, from the 3% pace currently.

So isn’t that enough tightening? Well not quite. The FCI isn’t great at capturing fiscal policy, namely the tax cuts from Trump. And that will add about 0.75 – 1% to growth, so we are back at about 2.75 – 3%. And that is too fast. So what size tightening in financial conditions do we need to see before the Fed can assume mission accomplished? We believe a further 1 to 1.25% from here on our measure. And where will that come from? Well typically it has come from bonds.

Which is one reason why we love being short bonds. All the more so because we expect term premium to be restored to bonds. And in October, there was genuine sign of this starting to happen.

And why not? After all, the reason for the suppression of term premium was global central bank purchases of bonds. Remember this chart?

And in October the ECB, as telegraphed, halved their purchases. Less telegraphed, the BOJ stepped down their purchases from USD 80 billion per month to USD 25 billion per month.

Source: Ellerston GMF, Bloomberg

So great, bonds are about to surge to the 3.75% to 4% level we have been talking about all year. Not so fast. Short bonds has been a frustrating trade this year, which has led to frustratingly flat returns for us and you as an investor. Why? Well they have not risen much. We have struggled since March with a range bound and choppy 10 year US bond.

Are we wrong? We ask that question every day. And what’s the answer? It’s complicated.

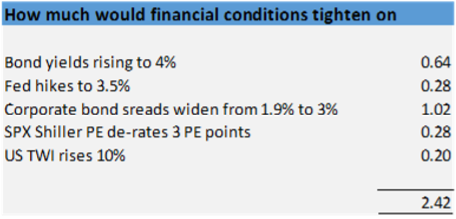

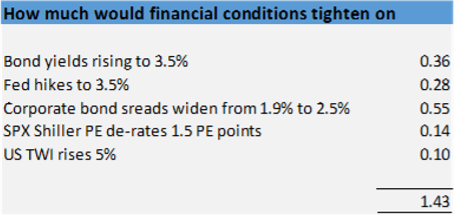

As the year has progressed, we have become more and more convinced that the US economy is overheating and it needs to slow. And hence more and more convinced that financial conditions need to tighten. But when you ask how, well, that is where the consequences of 10 years of quantitative easing come in. And the tariff battle. You see, the strong growth has locked the Fed in. They must slow the economy now, meaning they must tighten financial conditions. Ideally, like 04-06, that would be achieved by a slow and steady rise in the Fed Funds rate. With bond yields doing a strong assist. The table below shows how much the various components move our FCI. Our forecast of the Fed hiking to 3.5% and bond yields moving to 4% tightens the FCI by about 1%. The job is done with modest or no help from the other components of the FCI. But what if the help from other components isn’t modest? What if the equity market fell 20%? Or the currency rose 10%. Well frankly it doesn’t really matter that much. An instant 3 point de-rating of the PE ratio would create a fall of about 18% in equities. And shave only 0.28% from growth. And a 10% rise in the USD would only trim 0.2%. The so-called “Fed put” for the equity market is a long way away, and why you didn’t see them blink in October.

But look how punchy the corporate bond spread is. If that rose back to the levels that prevailed prior to QE, well, that does the bulk of the Fed’s (and bond market’s) work.

Will it?

Well put it this way. We wouldn’t be surprised. In June I wrote about the massive surge of lending to corporates over the last decade by investors hungry for yield. And we were looking for a catalyst for this flow to be reversed. The start of QT is one. But the real pressure is the Fed. Every time they hike, they reduce the return of foreign lenders. And the recent data is giving them no choice but to hike.

Tim reviews where the money has gone and what might break this month. With that, we have opened short positions in credit. In options. Again limited loss. Financial conditions need to tighten. It will be the Fed, or the rate charged to corporate borrowers. We have exposure to both.

And China? An agreement, or not, is massively important for how the FCI tightens. A “bad” outcome will see equities, the USD and corporate spreads do most of the tightening, rather than the Fed or bond yields. And a good outcome, the opposite.

So we want to be positioned for a tightening in the FCI. But how the FCI tightens depends on

- The outcome with China, (equities and credit do more of the work?)

- How quickly term premium and inflation premium is restored to bonds, (bonds do more of the work?)

- How quickly the global yield chase into credit is reversed (credit does more of the work?)

On the first, frankly I have changed my mind every week in the last month, perhaps subscribing a little too tightly to the famous Keynes quip “When the facts change I change my mind. What do you do sir?”

So what do I think on China? First let’s frame the conundrum.

- Initially China thought the tariff dispute would be resolved over coming months with some concessions

- Over the recent months, the suspicion built that the problem was somewhat more intractable. The Mike Pence speech at the Hudson institute not only confirmed that suspicion to the Chinese. It terrified them.

- The Chinese have bunkered down for a drawn out battle, planning to ease fiscal policy more, allowing the currency to gradually weaken towards, and easing lending. They even bought their own equity market. They were preparing for the worst.

- And then Trump reached out with a phone call on Thursday 1st November, followed by a tweet saying it was a “good” call, he will meet with Xi at the G20, and hopes to get a great agreement. Stock markets found a bottom, at least for now.

Which brings me back to the FCI. If China and the US reach an agreement, the stock market will rebound and the tightening in the FCI needs to come much more heavily from bonds and the Fed (which in turn will truncate the stock market rally, and the risk off/risk on dance will continue).

But if China and the US continue their battle, growth will be hurt, inflation will lift (via tariff increases), and a lot of the tightening in the FCI will come from corporate bond rates, the equity market and the USD. It might look something like this:

I don’t know what will happen in Buenos Aires. But I do know this. It is very important for markets. Have you stress tested your portfolio for a bad outcome? Oh, and don’t forget the risk of a wage acceleration. So how are we playing it?

Today (2nd November, and already different to the 30th October), we have 3 main exposures:

- Short US rates (mostly via options) from 2 to 30 years (captures growth, term premium and inflation).

- Short US investment grade and high yield credit, again via options (captures yield chase unwind, Fed hikes and bad China outcome).

- Long volatility in USDCNH over the Buenos Aires meeting (because who knows!).

This is premised on some optimism being maintained by markets into the G20 meeting of Xi and Trump. But we have to gauge this with every tweet. If pessimism builds, we will lighten the short US rate positon. Indeed, that is what has compromised our performance all year. Being short US rates is like being short volatility. Every time something goes wrong in the world, be it Brexit, Italian policies, VIX explosions or Facebook scandals, equities slump and bonds rally. And we have to respect that. After all, the FCI can tighten via other routes.

What I can say is this. It is a time to be very careful with your portfolio. Understand what is happening. Be very aware of what can blow up on you. And look for the tails. Indeed, the market fishtail is right in front of you. Are you safe?

The Ellerston Capital Global Macro Fund is an absolute, unconstrained strategy investing in a number of fundamentally derived core themes, optimised via trade expression and portfolio construction across Fixed Income, Foreign Exchange, Equity & Commodities. It focuses on capital preservation while providing low to negative correlation to traditional asset classes. Find out more.

5 topics

1 contributor mentioned

Brett has worked in the financial services industry for over 28 years. Most recently he was Head of Global Macro at Ellerston Capital. Prior to that he spent over 10 years as Senior Portfolio Manager at Tudor Investment Corporation.

Expertise

Brett has worked in the financial services industry for over 28 years. Most recently he was Head of Global Macro at Ellerston Capital. Prior to that he spent over 10 years as Senior Portfolio Manager at Tudor Investment Corporation.